Producing Bulgarian Yoghurt : Manufacturing and Exporting Authenticity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eric Kandel Form in Which This Information Is Stored

RESEARCH I NEWS pendent, this system would be expected to [2] HEEsch and J E Bums. Distance estimation work quite well, since the new recruit bees by foraging honeybees, The Journal ofExperi mental Biology, Vo1.199, pp. 155-162, 1996. tend to take the same route as the experi [3] M V Srinivasan, S W Zhang, M Lehrer, and T enced scout bee. What dOJhe ants do when S Collett, Honeybee Navigation en route to they cover similarly several kilometres on the goal: Visual flight control and odometry, foot to look for food? Preliminary evidence The Journal ofExperimental Biology, Vol. 199, pp. 237-244, 1996. indicates that they don't use an odometer but [4] M V Srinivasan, S W Zhang, M Altwein, and instead might count steps! J Tautz, Honeybee Navigation: Nature and Calibration of the Odometer, Science, Vol. Suggested Reading 287, pp. 851-853, 1996. [1] Karl von Frisch, The dance language and OT Moushumi Sen Sarma, Centre for Ecological Sci ientation of bees, Harvard Univ. Press, Cam ences, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore 560012, bridge, MA, USA, 1993. India. Email: [email protected] Learning from a Sea Snail: modify future behaviour, then memory is the Eric Kandel form in which this information is stored. Together, they represent one of the most valuable and powerful adaptations ever to Rohini Balakrishnan have evolved in nervous systems, for they In the year 2000, Eric Kandel shared the allow the future to access the past, conferring Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicinel flexibility to behaviour and improving the with two other neurobiologists: Arvid chances of survival in unpredictable, rapidly Carlsson and Paul Greengard. -

Introduction and Historical Perspective

Chapter 1 Introduction and Historical Perspective “ Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution. ” modified by the developmental history of the organism, Theodosius Dobzhansky its physiology – from cellular to systems levels – and by the social and physical environment. Finally, behaviors are shaped through evolutionary forces of natural selection OVERVIEW that optimize survival and reproduction ( Figure 1.1 ). Truly, the study of behavior provides us with a window through Behavioral genetics aims to understand the genetic which we can view much of biology. mechanisms that enable the nervous system to direct Understanding behaviors requires a multidisciplinary appropriate interactions between organisms and their perspective, with regulation of gene expression at its core. social and physical environments. Early scientific The emerging field of behavioral genetics is still taking explorations of animal behavior defined the fields shape and its boundaries are still being defined. Behavioral of experimental psychology and classical ethology. genetics has evolved through the merger of experimental Behavioral genetics has emerged as an interdisciplin- psychology and classical ethology with evolutionary biol- ary science at the interface of experimental psychology, ogy and genetics, and also incorporates aspects of neuro- classical ethology, genetics, and neuroscience. This science ( Figure 1.2 ). To gain a perspective on the current chapter provides a brief overview of the emergence of definition of this field, it is helpful -

Antimicrobial Effect and Antibiotic Resistance of Lactic Acid Bacteria from Some Commercial Dairy Products

Dinu L. et al./Scientific Papers: Animal Science and Biotechnologies, 2018, 51 (1) Antimicrobial Effect and Antibiotic Resistance of Lactic Acid Bacteria from some Commercial Dairy Products Laura-Dorina Dinu1, Silviu Ioan Babata1, Anca Nicoleta Ciurea1, Ana-Maria Lunita1 1University of Agronomic Sciences and Veterinary Medicine of Bucharest, Faculty of Biotechnology, 011464, Bucharest, Marasti Ave. 59, Romania Abstract Over the past few years lactic acid bacteria (LAB) have received considerable attention as probiotic commonly consumed in fermented foods, such as some yoghurts and fermented milk drinks, and claimed antimicrobial effects against different human pathogens. Therefore, the objective of the study was to investigate the antimicrobial activity of 24 commercial dairy products and the antibiotic resistance in LAB isolated from these products. The antimicrobial effect of commercial products on growth inhibition of Candida albicans and Salmonella enteritidis was investigated using disc diffusion method, while to test the antibiotic resistance of LAB isolated from dairy were used: ampicillin (SAM, 20 µg), amoxicillin (AMC, 30 µg), ciprofloxacin (CIP, 1 µg) and trimethroprim-sulfamethoxazole (STX, 25 µg). It was found that 8 fermented foods have antifungal activity and the highest effect was produced by Napolact Kefir and a probiotic yoghurt Leeb Vital Bio, but only 2 products (Covalact Sana, Danone Activia) maintained the antimicrobial effect in 7 days expired products. Covalact Sana, Napolact Sana Bio and Pilos (kefir and yoghurt) presented the highest antibacterial effect on Salmonella sp. strain. The study revealed high susceptibility of consortium LAB strains from tested dairy products to ampicillin. This preliminary research offers consumers supplementary information about the health benefits of some commercial dairy products. -

Consciousness Eclipsed: Jacques Loeb, Ivan P. Pavlov, and the Rise of Reductionistic Biology After 1900

Consciousness and Cognition Consciousness and Cognition 14 (2005) 219–230 www.elsevier.com/locate/concog Consciousness eclipsed: Jacques Loeb, Ivan P. Pavlov, and the rise of reductionistic biology after 1900 Ralph J. Greenspan*, Bernard J. Baars The Neurosciences Institute, 10640 John Jay Hopkins Dr., San Diego, CA 92121, United States Received 17 May 2004 Available online 25 November 2004 Abstract The life sciences in the 20th century were guided to a large extent by a reductionist program seeking to explain biological phenomena in terms of physics and chemistry. Two scientists who figured prominently in the establishment and dissemination of this program were Jacques Loeb in biology and Ivan P. Pavlov in psychological behaviorism. While neither succeeded in accounting for higher mental functions in physical- chemical terms, both adopted positions that reduced the problem of consciousness to the level of reflexes and associations. The intellectual origins of this view and the impediment to the study of consciousness as an object of inquiry in its own right that it may have imposed on peers, students, and those who followed is explored. Ó 2004 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Keywords: History of ideas; Reductionism; Tropism; Conditional reflex 1. Introduction The current acceptance of consciousness as a suitable object of study in the life sciences came late in the 20th century (Flanagan, 1984). By that time other biological processes—physiology, biochemistry, genetics, embryology, and even many aspects of brain function—had long since * Corresponding author. Fax: +1 858 626 2099. E-mail addresses: [email protected] (R.J. Greenspan), [email protected] (B.J. -

The Fessard's School of Neurophysiology After

The fessard’s School of neurophysiology after the Second World War in france: globalisation and diversity in neurophysiological research (1938-1955) Jean-Gaël Barbara To cite this version: Jean-Gaël Barbara. The fessard’s School of neurophysiology after the Second World War in france: globalisation and diversity in neurophysiological research (1938-1955). Archives Italiennes de Biologie, Universita degli Studi di Pisa, 2011. halshs-03090650 HAL Id: halshs-03090650 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03090650 Submitted on 11 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Fessard’s School of neurophysiology after the Second World War in France: globalization and diversity in neurophysiological research (1938-1955) Jean- Gaël Barbara Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, CNRS UMR 7102 Université Denis Diderot, Paris, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, CNRS UMR 7219 [email protected] Postal Address : JG Barbara, UPMC, case 14, 7 quai Saint Bernard, 75005, -

Cells of the Nervous System

3/23/2015 Nervous Systems | Principles of Biology from Nature Education contents Principles of Biology 126 Nervous Systems A flock of Canada geese use auditory and visual cues to maintain a V formation in flight. How are these animals able to respond so quickly to environmental cues? All animals possess neurons, cells that form a complex network capable of transmitting and receiving signals. This neural network forms the nervous system. The nervous system coordinates the movement and internal physiology of an organism, as well as its decisionmaking and behavior. In all but the simplest animals, neurons are bundled into nerves that facilitate signal transmission. More complex animals have a central nervous system (CNS) that includes the brain and nerve cords. Vertebrates also have a peripheral nervous system (PNS) that transmits signals between the body and the CNS. Cells of the Nervous System Structure of the neuron. Figure 1 shows the general structure of a neuron. The organelles and nucleus of a neuron are contained in a large central structure called the cell body, or soma. Most nerve cells also have multiple dendrites in addition to the cell body. Dendrites are short, branched extensions that receive signals from other neurons. Each neuron also has a single axon, a long extension that transmits signals to other cells. The point of attachment of the axon to the cell body is called the axon hillock. The other end of the axon is usually branched, and each branch ends in a synaptic terminal. The synaptic terminal forms a synapse, or junction, with another cell. -

Kandel and Hawkins

© 1992 SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN, INC The Biological Basis of Learnin and Individuality Recent discoveries suggestg that learning engages a simple set of rules that modify the strength of connections between neurons in the brain. These changes play an important role in making each individual unique by Eric R. Kandel and Robert D. Hawkins ver the past several decades, there surgeon at the Montreal Neurological Institute. has been a gradual merger of two In the 1940s Penfield began to use electri originally separate fields of science: cal stimulation to map motor, sensory and neurobiology,O the science of the brain, and language functions in the cortex of patients cognitive psychology, the science of the mind. undergoing neurosurgery for the relief of Recently the pace of unification has quick epilepsy. Because the brain itself does not ened, with the result that a new intellectual have pain receptors, brain surgery can be car framework has emerged for examining percep ried out under local anesthesia in fully con tion, language, memory and conscious aware scious patients, who can describe what they ness. This new framework is based on the abil experience in response to electric stimuli ap ity to study the biological substrates of these plied to different cortical areas. Penfield ex mental functions. A particularly faSCinating plored the cortical surface in more than 1,000 example can be seen in the study of learning. Elementary as patients. Occasionally he found that electrical stimulation pects of the neuronal mechanisms important for several dif produced an experiential response, or flashback, in which ferent types of learning can now be studied on the cellular the patients described a coherent recollection of an earlier and even on the molecular level. -

1. Overview 2. Database Architecture 3. Example Tree 6. Mentorship Network Influences?

Neurotree: Graphing the academic genealogy of neuroscience Stephen V. David1, Will Chertoff1, Titipat Achakulvisut2, Daniel Acuna2 1Oregon Health & Science University, 2Northwestern University 1. Overview 3. Example tree 4. Founding ancestors Neurotree (http://neurotree.org, [1]) is a collaborative, open-access Name N Resarch area Family tree The distance between two nodes can be Johannes Müller 7715 Physiology website that tracks and visualizes the academic genealogy and history P+ William Fitch measured by the number of mentorship Sir Charles Sherrington 4758 Neurophysiology of neuroscience. After 10 years of growth driven by user-generated Allen Hermann von Helmholtz 3048 Psychophysics University of P- steps connecting them through a Sir John Eccles 2998 Synapses content, the site has captured information about the mentorship of over Rudolf Oregon Ludwig Robert Samuel Alexander Sir Charles Medical common ancestor i(below). The list at Karl Lashley 2558 Learning and memory 80,000 neuroscientists. It has become a unique tool for a community of John Friedrich Karl Koch Sir Charles Kinnier Charles Gordon John Scott Sir Charles Harvey Sir Charles Karl Edgar School C+ Louis Agassiz 2241 Anatomy Sir Michael Newport Goltz Virchow Universität Scott Wilson Symonds Holmes Farquhar Sherrington Scott Williams Scott Spencer Wilder Douglas Frederic right shows the 30 most frequent primary researchers, students, journal editors, and the press. Once Foster Langley Kaiser-Wilhelms- Universität Berlin (ID Sherrington National Hospital, Queen National -

YOGURT Ancient Food in the 21St Century

YOGURT ancient food in the 21st century Ricardo Weill This book is the result of extensive research carried out in collaboration with more than ten specialists in general health, nutrition, paediatrics, biochemistry and microbiology, among other disciplines. All specialists consulted offered state-of-the-art scientific and academic information, which was then combined and woven into this single text describing yogurt from its very origin to industrial manufacture. YOGURT ANCIENT FOOD IN THE 21ST CENTURY Weill, Ricardo YOGURT, ancient food in the 21st century/Ricardo Weill; compiled by Alejandro Ferrari; illustrated by Florencia Abd and Juliana Vido. First edition, Buenos Aires: Asociación Civil Danone para la Nutrición, la Salud y la Calidad de Vida, 2017. 180 p.: ill.; 21 x 14 cm. ISBN 978-987-28033-4-6 1. Dairy Industry 2. History I. Ferrari, Alejandro, comp. II. Abd, Florencia, ill. III. Vido, Juliana, ill. IV. Title. CDD 338.1762142 First edition 2017 All rights reserved. This book is subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. © 2017 INDEX FOREWORD 9 INTRODUCTION 13 FOOD FERMENTATION: CHANCE AND OPPORTUNITY 16 YOGURT IN THE HISTORY OF MAN 28 THE PIONEERING WORK OF ÉLIE METCHNIKOFF 42 YOGURT PRODUCTION 56 MICROBIOTA: THE INDIGENOUS COMMUNITY 68 KEFIR, YOGURT’S OLDER BROTHER 80 YOGURT AND NATURAL IMMUNITY 90 YOGURT AND HEALTH PROMOTION 106 WHAT DO ARGENTINES EAT? 120 CONTROVERSIES IN NUTRITION 136 YOGURT IN EVERYDAY COOKING, BY NARDA LEPES 148 RECIPES WITH YOGURT, BY NARDA LEPES 152 REFERENCES 162 FOREWORD The first draft for this book was drawn up in Berlin in 2015, during the 12th European Nutrition Conference (Federation of European Nutrition Societies), over dinner with my dear friend Esteban Carmuega. -

Middle Eastern Cuisine

MIDDLE EASTERN CUISINE The term Middle Eastern cuisine refers to the various cuisines of the Middle East. Despite their similarities, there are considerable differences in climate and culture, so that the term is not particularly useful. Commonly used ingredients include pitas, honey, sesame seeds, sumac, chickpeas, mint and parsley. The Middle Eastern cuisines include: Arab cuisine Armenian cuisine Cuisine of Azerbaijan Assyrian cuisine Cypriot cuisine Egyptian cuisine Israeli cuisine Iraqi cuisine Iranian (Persian) cuisine Lebanese cuisine Palestinian cuisine Somali cuisine Syrian cuisine Turkish cuisine Yemeni cuisine ARAB CUISINE Arab cuisine is defined as the various regional cuisines spanning the Arab World from Iraq to Morocco to Somalia to Yemen, and incorporating Levantine, Egyptian and others. It has also been influenced to a degree by the cuisines of Turkey, Pakistan, Iran, India, the Berbers and other cultures of the peoples of the region before the cultural Arabization brought by genealogical Arabians during the Arabian Muslim conquests. HISTORY Originally, the Arabs of the Arabian Peninsula relied heavily on a diet of dates, wheat, barley, rice and meat, with little variety, with a heavy emphasis on yogurt products, such as labneh (yoghurt without butterfat). As the indigenous Semitic people of the peninsula wandered, so did their tastes and favored ingredients. There is a strong emphasis on the following items in Arabian cuisine: 1. Meat: lamb and chicken are the most used, beef and camel are also used to a lesser degree, other poultry is used in some regions, and, in coastal areas, fish. Pork is not commonly eaten--for Muslim Arabs, it is both a cultural taboo as well as being prohibited under Islamic law; many Christian Arabs also avoid pork as they have never acquired a taste for it. -

A NALWO Recipe Collection

A NALWO Recipe Collection from 25 Years of Cooking Demonstrations by the Women of Fermilab May 2011 This collection of recipes from past NALWO cooking demonstrations was selected and edited by Mady Newfield and Selitha Raja, with assistance from Annamaria Feher. This book is dedicated to Barbara Oddone, for her continuing support and encourage‐ ment, and to all those women in the history of Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory who helped, learned from, and befriended each other through NALWO, the National Accelerator Laboratory Women’s Organization. Table of Contents Chronological List of the past 25 years of NALWO cooking demonstrations and recipes iv Appetizers Cilantro Chutney for Sandwiches 1 Armenian Eggplant Caviar 2 Chopped Herring 2 Fish with Marinade 3 Salmon Spread 3 Man Doo 4 Classic Chopped Liver 5 Marinated Mushroom Appetizer 6 Pastelitos 7 Yingbo’s Chinese Dumplings 8 Soups Autumn Squash Soup 9 Chicken & Corn Chowder 10 Lentil or Split Pea Soup 11 Sopa de Tortilla 12 Spas (Barley Yogurt Soup) 13 Yogurt Corbasi 14 Salads Cucumber & Seaweed Salad 15 Bavarian Potato Salad 15 Cucumber Raita 16 Piyaz Bean Salad 16 Spinach salad with black sesame dressing 17 Sze‐Chuan Cucumber Relish 17 Sweet and Sour Cabbage Salad Peking Style 18 Vinaigrette Salad 18 Side Dishes Blini ‐ Russian crepes with yeast 19 California Chipotle Sweet Potatoes 20 Mexican Zucchini 20 Mexican Rice 21 Chole 22 ii Main Dishes Avial 23 Beef Rouladen with Braised Red Cabbage 24 Chop Chae 25 Hungarian Stuffed Potatoes 26 Kasha Varnishkes 27 Minted Trout 27 Ma‐Po -

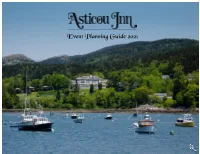

Asticou Inn Event Planning Guide 2021

Event Planning Guide 2021 1 The Asticou Inn Our Location Overlooking the picturesque, blue waters of Northeast Harbor, the Asticou Inn Uniquely positioned on the southern side of has been a tradition along the coast of Maine since 1883. An iconic setting for Mount Desert Island, the Asticou Inn allows you sophisticated weddings, and events. We offer an array of flexible venues and and your guests easy access to both Acadia spaces such as our Grand Lawn, Dining Room, Outdoor Patio, and our private National Park, the Village of Northeast Harbor, dining room the Harbor View Room. Our location provides an exquisite and the Northeast Harbor Pier. The Stanley backdrop for your special occasion. Brook entrance, a major gateway into Acadia, is just under three miles away. Carriage trails can be accessed just over half a mile from the inn at the Brown Mountain Gate House. Footpaths begin both on property with the Asticou Trail leading to local conservation trails, and across the street with trails leading into the National Park. The Asticou Azalea and Thuya Gardens are within easy walking distance. The Beal and Bunker mailboat provide transportation from Northeast Harbor to the nearby Cranberry Islands. The Sea Princess offers tours throughout the day. Wildwood Stables, located 4 miles from the Inn, offers carriage rides. There is a multitude of activities for your guests to enjoy. 2 3 Special Events Fees and Requirements General Capacity Guidelines and Costs Full Property $7,000 - A full property fee includes the use of the entire restaurant, bar, lounge, common rooms, covered porch, and deck for the duration of your event.