Press Release - March 2021]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Landscapes of Korean and Korean American Biblical Interpretation

BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION AMERICAN AND KOREAN LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN International Voices in Biblical Studies In this first of its kind collection of Korean and Korean American Landscapes of Korean biblical interpretation, essays by established and emerging scholars reflect a range of historical, textual, feminist, sociological, theological, and postcolonial readings. Contributors draw upon ancient contexts and Korean American and even recent events in South Korea to shed light on familiar passages such as King Manasseh read through the Sewol Ferry Tragedy, David and Bathsheba’s narrative as the backdrop to the prohibition against Biblical Interpretation adultery, rereading the virtuous women in Proverbs 31:10–31 through a Korean woman’s experience, visualizing the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) and demarcations in Galatians, and introducing the extrabiblical story of Eve and Norea, her daughter, through story (re)telling. This volume of essays introduces Korean and Korean American biblical interpretation to scholars and students interested in both traditional and contemporary contextual interpretations. Exile as Forced Migration JOHN AHN is AssociateThe Prophets Professor Speak of Hebrew on Forced Bible Migration at Howard University ThusSchool Says of Divinity.the LORD: He Essays is the on author the Former of and Latter Prophets in (2010) Honor ofand Robert coeditor R. Wilson of (2015) and (2009). Ahn Electronic open access edition (ISBN 978-0-88414-379-6) available at http://ivbs.sbl-site.org/home.aspx Edited by John Ahn LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN AND KOREAN AMERICAN BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION INTERNATIONAL VOICES IN BIBLICAL STUDIES Jione Havea Jin Young Choi Musa W. Dube David Joy Nasili Vaka’uta Gerald O. West Number 10 LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN AND KOREAN AMERICAN BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION Edited by John Ahn Atlanta Copyright © 2019 by SBL Press All rights reserved. -

Surviving Through the Post-Cold War Era: the Evolution of Foreign Policy in North Korea

UC Berkeley Berkeley Undergraduate Journal Title Surviving Through The Post-Cold War Era: The Evolution of Foreign Policy In North Korea Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4nj1x91n Journal Berkeley Undergraduate Journal, 21(2) ISSN 1099-5331 Author Yee, Samuel Publication Date 2008 DOI 10.5070/B3212007665 Peer reviewed|Undergraduate eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Introduction “When the establishment of ‘diplomatic relations’ with south Korea by the Soviet Union is viewed from another angle, no matter what their subjective intentions may be, it, in the final analysis, cannot be construed otherwise than openly joining the United States in its basic strategy aimed at freezing the division of Korea into ‘two Koreas,’ isolating us internationally and guiding us to ‘opening’ and thus overthrowing the socialist system in our country [….] However, our people will march forward, full of confidence in victory, without vacillation in any wind, under the unfurled banner of the Juche1 idea and defend their socialist position as an impregnable fortress.” 2 The Rodong Sinmun article quoted above was published in October 5, 1990, and was written as a response to the establishment of diplomatic relations between the Soviet Union, a critical ally for the North Korean regime, and South Korea, its archrival. The North Korean government’s main reactions to the changes taking place in the international environment during this time are illustrated clearly in this passage: fear of increased isolation, apprehension of external threats, and resistance to reform. The transformation of the international situation between the years of 1989 and 1992 presented a daunting challenge for the already struggling North Korean government. -

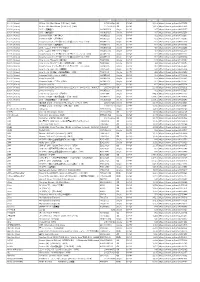

アーティスト 商品名 品番 ジャンル名 定価 URL 100% (Korea) RE

アーティスト 商品名 品番 ジャンル名 定価 URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 K-POP 2,290 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 K-POP 2,290 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 K-POP 1,296 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 K-POP 1,296 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 K-POP 648 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 K-POP 648 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 100% (Korea) How to cry (ミヌ盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5005 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415958 100% (Korea) How to cry (ロクヒョン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5006 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415970 100% (Korea) How to cry (ジョンファン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5007 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415972 100% (Korea) How to cry (チャンヨン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5008 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415974 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you (A) OKCK5011 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655024 100% (Korea) Song for you (B) OKCK5012 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655026 100% (Korea) Song for you (C) OKCK5013 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655027 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) -

URL 100% (Korea)

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマッ ジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤C> OKCK5022 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732096 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤B> OKCK5021 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732095 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (チャンヨン)(LTD) OKCK5017 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655033 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤A> OKCK5020 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732093 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ジョンファン)(LTD) OKCK5016 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655032 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ヒョクジン)(LTD) OKCK5018 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655034 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 Single K-POP 421 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 -

Block B Album Download Block B Members Profile

block b album download Block B Members Profile. Block B (블락비) currently consists of: Zico, Taeil, B-Bomb, Jaehyo, U-Kwon, Kyung, and P.O . Leader Zico left the company on November 23, 2018, however according to Seven Seasons , the future of the band as a 7-members band is still under discussion. The band debuted on April 13, 2011, under Stardom Entertainment. In 2013, they left their agency and signed with Seven Seasons, a subsidiary label to KQ Entertainment. Block B Fandom Name: BBC (Block B Club) Block B Official Fan Color: Black and Yellow Stripes. Block B Official Accounts: Twitter: @blockb_official Facebook: BlockBOfficial Instagram: @blockb_official_ Fan cafe: BB-Club. Block B Members Profile: Zico Stage Name: Zico (지코) Birth Name: Woo Ji Ho (우지호) Position: Leader, Main Rapper, Vocalist, Face of the Group Birthday: September 14, 1992 Zodiac Sign: Virgo Birthplace: Seoul, South Korea Height: 181 cm (5’11”) Weight: 65 kg (143 lbs) Blood Type: O Twitter: @ZICO92 Instagram: @woozico0914. Zico Facts: – He was born in Mapo, Seoul, South Korea. – He has an older brother, Woo Taewoon, who was a former member of idol group Speed. – He was a Vocal Performance major at Seoul Music High School. – Zico studied at the Dong-Ah Institute of Media and Arts University (between 2013 -2015). – Specialties: Freestyle rap, composing, weaving melody lines. – He auditioned for S.M. Entertainment as a teenager. – He joined Stardom Entertainment in 2009. – Zico lived abroad in Japan for three years. – On November 7, 2014, Zico released his official solo debut single entitled “Tough Cookie” featuring the rapper Don Mills – He, along with Kyung have produced all of Block B’s albums. -

STATEMENT UPR Pre-Session 33 on the Democratic People's Republic

STATEMENT UPR Pre-Session 33 on the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) Geneva, April 5, 2019 Delivered by: The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea (HRNK) 1- Presentation of the Organization HRNK is the leading U.S.-based bipartisan, non-governmental organization (NGO) in the field of DPRK human rights research and advocacy. Our mission is to focus international attention on human rights abuses in the DPRK and advocate for an improvement in the lives of 25 million DPRK citizens. Since its establishment in 2001, HRNK has played an intellectual leadership role in DPRK human rights issues by publishing over thirty-five major reports. HRNK was granted UN consultative status on April 17, 2018 by the 54-member UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). On October 4, 2018, HRNK submitted our findings to the UPR of the DPRK. Based on our research, the following trends have defined the human rights situation in the DPRK over the past seven years: an intensive crackdown on attempted escape from the country leading to a higher number of prisoners in detention; a closure of prison camps near the border with China while camps inland were expanded; satellite imagery analysis revealing secure perimeters inside these detention facilities with watch towers seemingly located to provide overlapping fields of fire to prevent escapes; a disproportionate repression of women (800 out of 1000 women at Camp No. 12 were forcibly repatriated); and an aggressive purge of senior officials. 2- National consultation for the drafting of the national report Although HRNK would welcome consultation and in-country access to assess the human rights situation, the DPRK government displays a consistently antagonistic attitude towards our organization. -

Download Ordinary Love Kyung Park Blok B

Download ordinary love kyung park blok b CLICK TO DOWNLOAD 보통의 순간이 특별하게 다가오는 순간.박경 "보통연애" 블락비 박경 자정 "보통연애" 발표 '국민연애송 자리 노린다' 블락비의 박경이 20일 자정 "보통연애"를 발표하고 대중 취향 저격에 나선다. 블락비의 박경과 박보람이 함께 한 "보통연애"는 남다른 송 라이팅 실력을 보여주고 있는 박경과. Lyrics to 'Ordinary Love' by Park Kyung Feat. Park Boram. 새로운 사람, 흥미가 생기고 / 뻔하 디 뻔한 말들을 주고받다 / 서로 눈치채고 있는 타이밍에 / 용기 내 하는 취중고백 / 끼워 맞추듯 취미를 공유하고 / '야!'라 부르던 네가 자기가 되도 / 너무나 익숙한 장면 같아 / 반복되는 déjà vu / 너도 느끼잖아 이거 좀. 9. · popgasa Park Bo Ram, Park Kyung (Block B) block b, english, 보통연애, kpop, lirik lagu, lyrics, ordinary love, park bo ram, park kyung, translation 2 Comments A new person, having interest Give and take obvious words. Video Ordinary Love do ca sĩ Park Kyung (Block B), Park Bo Ram thể hiện, thuộc thể loại Video Nhạc Hàn. Các bạn có thể nghe, download MV/Video Ordinary Love miễn phí tại renuzap.podarokideal.ru · "Ordinary Love" (보통연애) is the debut digital single by Park Kyung of Block B. It was released on September 21, and features the vocals of Park Boram. Music video Teaser 1 / 2Composer(s): Park Kyung, Kero One. Title of Single: Space Oddity Project Vol Artist: 박경 Park Kyung. Release date: Genre: Rap Hip-hop. Language: Korean. Tracks: 2 Quality: MPkbps. Listen to Three W's and One H by Park Kyung Feat. Jo Hyun Ah, 3, Shazams, featuring on BLOCK B Essentials Apple Music playlist. Park Kyung debut sebagai penyanyi solo di tahun dengan lagu Ordinary Love. -

South Korean Identities in Strategies of Engagement with North Korea: a Case Study of President Kim Dae-Jung's Sunshine Policy

South Korean Identities in Strategies of Engagement with North Korea: A Case Study of President Kim Dae-jung's Sunshine Policy Volume II Son Key-young A dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy GRADUATE SCHOOL Of EAST ASIAN STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF SHEFFIELD June 2004 Chapter Six. Case Study II: Hyundai's Mt. Kumgang Tourism Project 1. Introduction This case study seeks to bring to light the interplay of mUltiple actors and their diverse ideas involved in a controversial cross-border tourism project implemented by Hyundai, one of the largest South Korean conglomerates, and their collective contributions to South Koreans' identity shifts vis-a-vis North Korea and inter-Korean economic integration. The inseparability between the Hyundai project and President Kim's Sunshine Policy raises the two conflicting questions: 'was the Hyundai project simply a brainchild of the Sunshine Policy?' or 'was it the Hyundai project that helped jumpstart the Sunshine Policy and rescued the initially ill-fated policy?,l These questions are reminiscent of the time-honoured query: 'What came first, the chicken or the egg?' In fact, the strategic convergence of the Sunshine Policy and the Hyundai project made it possible for South Koreans to travel to North Korea for the first time in five decades of national division. Therefore, supporters of the Sunshine Policy shed light on the project's historical significance as a catalyst for trust building, reconciliation and economic integration between North and South Korea (Moon 1999; Kim and Yoon 1999; Koh 200 1; Kim K.S. 2002), while its critics highlight the project's shortcomings in terms of transparency, reciprocity, market principles and financial viability (Tait 2003; Levin and Han 2002). -

Gendered Practices and Conceptions in Korean Drumming: on the Negotiation of "Femininity" and "Masculinity" by Korean Female Drummers

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 Gendered Practices and Conceptions in Korean Drumming: On the Negotiation of "Femininity" and "Masculinity" by Korean Female Drummers Yoonjah Choi Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/413 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Gendered Practices and Conceptions in Korean Drumming: On the Negotiation of “Femininity” and “Masculinity” by Korean Female Drummers by Yoonjah Choi A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 2014 Yoonjah Choi All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Emily Wilbourne, Chair of Examining Committee Date Norman Carey, Executive Officer Professor Jane Sugarman Professor Peter Manuel Professor Anderson Sutton Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract Gendered Practices and Conceptions in Korean Drumming: On the Negotiation of “Femininity” and “Masculinity” by Korean Female Drummers by Yoonjah Choi Ph.D. in Ethnomusicology Advisor: Professor Jane Sugarman Korean drumming, one of the most popular musical practices in South Korea, currently exists in a state of contradiction as drumming, historically performed by men, is increasingly practiced by women. -

10 FRANCSS 10 Francs, 28 Rue De L'equerre, Paris, France 75019 France, Tel: + 33 1 487 44 377 Fax: + 33 1 487 48 265

MIPTV - MIPDOC 2013 PRE-MARKET UNABRIDGED COMPREHENSIVE PRODUCT GUIDE SPONSORED BY: NU IMAGE – MILLENNIUM FILMS SINCE 1998 10 FRANCSS 10 Francs, 28 Rue de l'Equerre, Paris, France 75019 France, Tel: + 33 1 487 44 377 Fax: + 33 1 487 48 265. www.10francs.fr, [email protected] Distributor At MIPTV: Christelle Quillévéré (Sales executive) Market Stand: MEDIA Stand N°H4.35, Tel: + 33 6 628 04 377 Fax: + 33 1 487 48 265 COLORS OF MATH Science, Education (60') Language: English Russian, German, Finnish, Swedish Director: Ekaterina Erementp Producer: EE Films Year of Production: 2011 To most people math appears abstract, mysterious, complicated, inaccessible. But math is nothing but another language to express the world. Math can be sensual. Math can be tasted, it smells, it creates sound and color. One can touch it - and be touched by it... Incredible Casting : Cedric Villani (french - he talks about « Taste »). Anatoly Fomenko (russian - he talks about « Sight »), Aaditya V. Rangan (american - he talks about « Smell »), Gunther Ziegler (german - he talks about « To touch » and « Geométry »), Jean- Michel Bismut (french - he talks about « Sound » … the sound of soul …), Maxime Kontsevich (russian - he talks about « Balance »). WILD ONE Sport & Adventure, Human Stories (52') Language: English Director: Jure Breceljnik Producer: Film IT Country of Origin: 2012 "The quest of a young man, athlete and disabled, to find the love of his mother and resolve the past" In 1977, Philippe Ribière is born in Martinique with the Rubinstein-Taybi Syndrome. Abandoned by his parents, he is left to the hospital, where he is bound to spend the first four years of his life and undergo a series of arm and leg operations. -

Modern Korean Economy: 1948–2008 Written by Yongjin Park

UNDERSTANDING KOREA SERIES No. 1 Hangeul Written by Lee Ji-young Understanding Korea No. 8 No. 2 Early Printings in Korea outh Korea is known for its rapid and continuous economic ECONOMY ECONOMY KOREAN MODERN Written by Ok Young Jung Sgrowth in the latter half of the 20th century. After liberation from Japanese colonial rule in 1945 and the Korean War About the series No. 3 Korean Confucianism: Tradition and Modernity (1950‒53), Korea has seen its per capita GDP shooting up from Written by Edward Y. J. Chung just US$290 in 1960 to an amazing US$28,384 in 2010. The Understanding Korea Series aims to share a variety MODERN KOREAN of original and fascinating aspects of Korea with those This book looks at the country’s modern economic overseas who are engaged in education or are deeply No. 4 Seoul development starting from the end of the Korean War, the Written by Park Moon-ho interested in Korean culture. economic problems Korea faced after the conflict, efforts to solve ECONOMY No. 5 A Cultural History of the Korean House these problems, and the results produced. It will also describe 1948–2008 Written by Jeon BongHee changes in economic policy objectives from liberation from Japanese colonial rule in 1945 through today in detail. No. 6 Korea’s Religious Places Written by Mark Peterson Yongjin Park No. 7 Geography of Korea Written by Kwon Sangcheol, Kim Jonghyuk, Lee Eui-Han, Jung Chi-Young No. 8 Modern Korean Economy: 1948–2008 Written by Yongjin Park ISBN 979-11-5866-427-5 Not for sale Cover Photo The night view of Seoul © gettyimages Korea Cover Design Jung Hyun-young, Cynthia Fernandez Modern Korean Economy Understanding Korea No. -

South Korean Men and the Military: the Influence of Conscription on the Political Behavior of South Korean Males

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2015 South Korean Men and the Military: The nflueI nce of Conscription on the Political Behavior of South Korean Males Hyo Sung Joo Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Joo, Hyo Sung, "South Korean Men and the Military: The nflueI nce of Conscription on the Political Behavior of South Korean Males" (2015). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 1048. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/1048 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT MCKENNA COLLEGE South Korean Men and the Military: The Influence of Conscription on the Political Behavior of South Korean Males SUBMITTED TO Professor Jennifer M. Taw AND Dean Nicholas Warner BY Hyo Sung Joo for SENIOR THESIS Fall 2014 December 1st, 2014 2 3 ABSTRACT This thesis evaluates the effects of compulsory military service in South Korea on the political behavior of men from a public policy standpoint. I take an institutional point of view on conscription, in that conscription forces the military to accept individuals with minimal screening. Given the distinct set of values embodied by the military, I hypothesize that the military would need a powerful, comprehensive, and fast program of indoctrination to re-socialize civilians into military uniform, trustable enough to be entrusted with a gun or a confidential document. Based on the existence of such a program and related academic literature, I go on to look at how a military attitude has political implications, especially for the security-environment of the Korean peninsula.