The Gamut Looks at Cleveland, Special Edition, 1986

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lending Is Back for Big-Ticket Property

20111121-NEWS--1-NAT-CCI-CL_-- 11/18/2011 3:21 PM Page 1 $2.00/NOVEMBER 21 - 27, 2011 With skills Lending is in demand, back for area trade big-ticket schools rise property PowerSport Institute, tech college eye growth But preference goes to newer commercial By DAN SHINGLER [email protected] sites with low vacancy With a lot of people looking to By STAN BULLARD switch careers or pursue an educa- [email protected] tion in something more pragmatic and potentially profitable than, say, Commercial real estate lending in literary history, the Cleveland-based Northeast Ohio has begun its journey Ohio Technical College and its Power- down the comeback trail, though Sport Institute in North Randall have obstacles remain for developers and had little trouble finding new students property buyers that are keeping the during the economic slump. path to loans from being as smooth As a result, the trade schools as it was prior to the 2008 financial have continued to grow, said Marc crisis. Brenner, the owner of both. Now Mr. Two recent deals are illustrative of Brenner might develop a campus in recovery — at least in the Class A, or Cleveland or take over more space high, end of the commercial market. in long-suffering Randall Park Mall, In our first Forty Under 40 choosing which folks to include.” First Interstate Properties Ltd., where the PowerSport Institute section — published Oct. 28, It’s a challenge we’ve faced for through an affiliate, secured a $5 already is the largest tenant. 1991 — Crain’s editor Mark 20 years, picking from a bevy of million mortgage Oct. -

Annual Events 2019 Calendar

Annual events 2019 Calendar Seasonal Events September-December March September 2018 – June 2019 NFL Cleveland Browns Regular Season 3/2: Cleveland Kurentovanje FirstEnergy Stadium, Various locations, St. Clair-Superior The Cleveland Orchestra at Downtown Cleveland neighborhood Severance Hall www.clevelandbrowns.com www.clevelandkurentovanje.com University Circle www.clevelandorchestra.com November-December 3/8-10: Wizard World Comic Con Huntington Convention Center of October 2018 – April 2019 Black Nativity at Karamu House Cleveland, Downtown Cleveland Karamu House, Fairfax wizardworld.com/comiccon/cleveland NBA Cleveland Cavaliers karamuhouse.org Regular Season 3/13-16: MAC Men’s & Women’s Quicken Loans Arena, November-January Basketball Tournament Downtown Cleveland GLOW at Cleveland Botanical Garden Quicken Loans Arena, www.cavs.com Cleveland Botanical Garden, Downtown Cleveland getsomemaction.com AHL Cleveland Monsters University Circle www.cbgarden.org Regular Season 3/17: St. Patrick’s Day Parade Quicken Loans Arena, Various locations, Downtown Cleveland Downtown Cleveland Events by Month www.stpatricksdaycleveland.com www.clevelandmonsters.com 3/20-24: Be A Tourist in April-September January Your Hometown Various locations MLB Cleveland Indians Regular Season 1/17-21: Cleveland Boat Show VisitMeInCLE.com Progressive Field, Downtown Cleveland I-X Center, West Park www.indians.com www.clevelandboatshow.com 3/27-4/7: Cleveland International MiLB Akron RubberDucks Film Festival 1/20: Martin Luther King, Jr. Tower City Cinemas, Regular -

Lake View Cemetery Cleveland’S Outdoor Museum and Arboretum Pat Mraz, MG ‘07

Trumpet Vine July/August 2009 12 Lake View Cemetery Cleveland’s Outdoor Museum and Arboretum Pat Mraz, MG ‘07 On May 19, 2009 a group of Master plain (sections near Euclid gate) to loamy Gardeners took a Horticultural walking tour soils to clay. of Lake View Cemetery led by Lake View Several of us were surprised to see many Horticulturist Dave Gressley. Founded in graves covered with English Ivy instead of 1869, Lake View Cemetery sits on 285 acres grass. Dave said that Ivy is an option at Lake of land (70 undeveloped) in Cleveland, East View and that since it is an evergreen, it Cleveland and Cleveland Heights. It was serves as a symbol of everlasting life. modeled after the great garden cemeteries of Victorian England and France. Along the way we noted that the Sycamore trees did not look very healthy. Dave ex- In keeping with its garden-like design, plained that the Sycamores were plagued by Lake View is home to many rare and in- anthracnose last year and are late in leafing teresting flowers, plants, and trees. This out this year. But Buckeyes, Horse Chestnuts includes “Daffodil Hill”, a section of the and Tulip trees were all in flower. cemetery that contains over 100,000 daffodil bulbs, as well as the Moses Cleveland tree The west branch of Dugway Brook passes and numerous Japanese Threadleaf Maple through Cleveland Heights as an open trees. channel at several points and inside historic Lake View Cemetery. The cemetery quarried Designed by Adolph Strauch, the ceme- Euclid bluestone, a desirable, dense, finely- tery was meant to resemble Victorian English grained and easily-cut variety of sandstone, and French cemeteries. -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation

.NFS Form. 10-900-b ,, .... .... , ...... 0MB No 1024-0018 (Jan. 1987) . ...- United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form NATIONAL REGISTER This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing_________________________________ Historic and Architectural Resources of the lower Prospect/Huron _____District of Cleveland, Ohio________________________ B. Associated Historic Contexts Commercial Development of Downtown Cleveland, C. Geographical Data___________________________________________________ Downtown Cleveland, Ohio, bounded approximately by Ontario Street, Huron Road NW, and West 9th Street on the west; Lake Brie on the north; and the Innerbelt Jreeway on the east and south* I I See continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in>36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. 2-3-93 _____ Signature of certifying official Date Ohio Historic Preservation Office State or Federal agency and bureau I, hereby, certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related properties for listing in the National Register. -

Redevelopment Opportunity

101,104 SF (2.32 AC) REDEVELOPMENT REDEVELOPMENT SITE WITH IMMEDIATE ACCESS TO NEW OPPORTUNITY OPPORTUNITY CORRIDOR Cedar Ave. NEWLY BUILT Stokes Blvd. Development Site PPN 12124021 PPN 12124024 2.32 Acres Carnegie Ave. 10820-10822 & 10900 Carnegie Ave., Cleveland, OH • Central location in the heart of the University Circle • High-rise development potential, comparable to One • Development options may include medical offices • Adjacent properties can be combined to create a University Circle, (1 block north) and/or health-care providers,multi-family or student total land site of approx 132,000 SF (3.01 acres) • Existing 5 story office building w/ large parking lot, housing, research, institutional administrative, offices credit tenant will provide a one year leaseback. This for accounting firms, law firms, insurance, financial • Existing 22 unit apartment building with on-site planning, venture capital users, etc. parking, remains 100% occupied w/ excellent NOI combined income will provide resources to buyer while development plans proceed • Asking price: $45/SF of land area Bob Nosal, SIOR 216.469.5512 • [email protected] NO WARRANTY OR REPRESENTATION, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, IS MADE AS TO THE ACCURACY OF THE INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN, 6155 Rockside Road, Suite 304 AND THE SAME IS SUBMITTED SUBJECT TO ERRORS, OMISSIONS, CHANGE OF PRICE, RENTAL OR OTHER CONDITIONS, PRIOR SALE, Independence, Ohio 44131 LEASE OR FINANCING, OR WITHDRAWAL WITHOUT NOTICE, AND OF ANY SPECIAL LISTING CONDITIONS IMPOSED BY OUR PRINCIPALS NO +1 216 831 3310 WARRANTIES OR REPRESENTATIONS ARE MADE AS TO THE CONDITION OF THE PROPERTY OR ANY HAZARDS CONTAINED THEREIN ARE ANY TO BE IMPLIED. -

Ohio, the Commencement Was Strange,” Said Louis Gol- Speaker Richard Poutney Advised Phin, Who Lives Next Door

SPORTS MENU TIPS Cadillac show to be held Kid’s Corner Arts Center to present a Cotton Ball The Cadillac LaSalle Club will be hosting the Foluke Cultural Arts Center, Inc. will present it’s “Legacy of Cadillac” show on Sunday, august 19 from 10:00 Ronette Kendell Bell-Moore, first Cotton Ball, (dinner dance) on Saturday, July 28 at Ivy’s Raynell Williams Turn Your Picnic a.m. until 4:00 p.m. at Legacy Village, at the corner of Rich- who is two and a half years old and Catering at GreenMont, 800 S. Green Road from 9 p.m. - 2 mond and Cedar Roads in Lyndhurst. The show is a free, fam- a.m. The attire is casual summer white and tickets are $20.00 Wins Boxing Title Into A Party the daughter of Kendall Moore and ily friendly event. Fins, food, fashions and fun will rule as Jemonica Bell. Her favorite food is in advance and $25.00 the day of the event. A free cruise will be given away as a door prixze. Winner must be present. over 100 classic Cadillacs of all years and types will compete cheese and watermelon. Her favorite for trophies to be awarded at 3:00 p.m. This will be the largest Proceeds benefit Arts Center programming for children and See Page 6 See Page 7 and most prestigious gathering of important Cadillacs in seven toy and character is Dora. She has a youth in need. For information, please refer to www.foluke- states. For information, call Chris Axelrod, (216) 451-2161. -

Minutes of the Regular Meeting of the Board of Trustees Monday, November 13, 2017

Minutes of the Regular Meeting of the Board of Trustees Monday, November 13, 2017 A meeting of the Cuyahoga Arts & Culture (CAC) Board of Trustees was called to order at 4:13 pm at the Cleveland History Center, 10825 East Blvd., Cleveland, Ohio 44106. The roll call showed that Trustees Avsec, Garth, Gibbons, Miller and Sherman were present. It was determined that there was a quorum. Also in attendance were: CAC staff: Karen Gahl-Mills, executive director; Jill Paulsen, deputy director; Roshi Ahmadian; Meg Harris; Dan McLaughlin; India Pierre-Ingram; and Jake Sinatra. 1. APPROVAL OF MINUTES Trustee Gibbons moved to approve the minutes from the September 11 and October 16, 2017 Board meetings. Trustee Sherman stated that prior to seconding the approval she had some updates to the minutes which she would like to see reflected therein. Regarding the September 11 meeting, Trustee Sherman had stated that she would like CAC to request that the Musical Arts Association look into acquiring weather insurance for the concert in downtown Cleveland for which CAC will provide a $150,000 grant. Regarding the October 16 minutes, she asked that the minutes reflect her question to CAC staff regarding whether or not all GOS organizations had been talked to in advance of the reduced allocation to the GOS. The record should also show that this question had been answered in the affirmative. Motion by Trustee Gibbons, seconded by Trustee Sherman, to approve the minutes, as amended, from the September 11, 2017 and October 16, 2017 Board meetings. Discussion: None. Vote: all ayes. The motion carried. -

CMA Landscape Master Plan

THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART LANDSCAPE MASTER PLAN DECEMBER 2018 LANDSCAPE MASTER PLAN The rehabilitation of the Cleveland Museum of Art’s grounds requires the creativity, collaboration, and commitment of many talents, with contributions from the design team, project stakeholders, and the grounds’ existing and intended users. Throughout the planning process, all have agreed, without question, that the Fine Arts Garden is at once a work of landscape art, a treasured Cleveland landmark, and an indispensable community asset. But the landscape is also a complex organism—one that requires the balance of public use with consistency and harmony of expression. We also understand that a successful modern public space must provide more than mere ceremonial or psychological benefits. To satisfy the CMA’s strategic planning goals and to fulfill the expectations of contemporary users, the museum grounds should also accommodate as varied a mix of activities as possible. We see our charge as remaining faithful to the spirit of the gardens’ original aesthetic intentions while simultaneously magnifying the rehabilitation, ecological health, activation, and accessibility of the grounds, together with critical comprehensive maintenance. This plan is intended to be both practical and aspirational, a great forward thrust for the benefit of all the people forever. 0' 50' 100' 200' 2 The Cleveland Museum of Art Landscape Master Plan 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS CMA Landscape Master Plan Committee Consultants William Griswold Director and President Sasaki Heather Lemonedes -

Exploring Cleveland Arts, Culture, Sports, and Parks

ACRL 2019 Laura M. Ponikvar and Mark L. Clemente Exploring Cleveland Arts, culture, sports, and parks e’re all very excited to have you join us mall and one of Cleveland’s most iconic W April 10–13, 2019, in Cleveland for the landmarks. It has many unique stores, a ACRL 2019 conference. Cleveland’s vibrant food court, and gorgeous architecture. arts, cultural, sports, and recreational scenes, • A Christmas Story House and Mu- anchored by world-class art museums, per- seum (http://www.achristmasstoryhouse. forming arts insti- com) is located tutions, music ven- in Cleveland’s ues, professional Tremont neigh- sports teams, his- borhood and was toric landmarks, the actual house and a tapestry of seen in the iconic city and national film, A Christmas parks, offer im- Story. It’s filled mense opportuni- with props and ties to anyone wanting to explore the rich costumes, as well as some fun, behind- offerings of this diverse midwestern city. the-scenes photos. • Dittrick Medical History Center Historical museums, monuments, (http://artsci.case.edu/dittrick/museum) and landmarks is located on the campus of Case Western • Cleveland History Center: A Museum Reserve University and explores the history of the Western Reserve Historical Society of medicine through exhibits, artifacts, rare (https://www.wrhs.org). The Western Re- books, and more. serve Historical Society is the oldest existing • Dunham Tavern Museum (http:// cultural institution in Cleveland with proper- dunhamtavern.org) is located on Euclid ties throughout the region, but its Cleveland Avenue, and is the oldest building in Cleve- History Center museum in University Circle is land. -

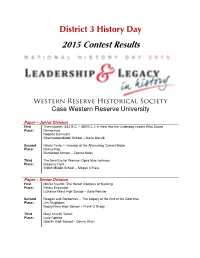

2015 Contest Results

District 3 History Day 2015 Contest Results Western Reserve Historical Society Case Western Reserve University Paper – Junior Division First Themistocles (524 B.C. – 459 B.C.): A View Into the Underdog Leader Who Saved Place: Democracy Roberto Demarchi Beachwood Middle School – Maria Marsilli Second Nikola Tesla — Inventor of the Alternating Current Motor Place: Rishav Roy Birchwood School -- Connie Miller Third The New Era for Woman: Opha Mae Johnson Place: Breanna Trent Shiloh Middle School -- Megan O'Hara Paper – Senior Division First Minnie Vautrin: The Heroic Goddess of Nanking Place: Felicia Escandon Lutheran West High School – Dave Ressler Second Reagan and Gorbachev -- The Legacy of the End of the Cold War Place: Jim Fitzgibbon Rocky River High School – Frank O’Grady Third Mary Church Terrell Place: Lucy Cipinko Oberlin High School – Donna Shurr Website – Junior Individual Division First John D. Rockefeller : Industrial & Philanthropic Leader Place: J. Victor Pan Birchwood School – Connie Miller Second Florence Nightingale : A Legacy of Innovative Medical Care Place: Farah Sayed Birchwood School – Connie Miller Third Lewis Hine : Taking the Lead to Expose the Dangers of Child Labor Place: Zuha Jaffar Birchwood School – Connie Miller Website – Senior Individual Division First Rabbi Arthur J. Lelyveld : "A Man Obsessed with Peace" Place: Jeremy Gimbel Shaker Heights High School – Tim Mitchell Second Why We Live Apart : Institutionalized Segregation in the 20th Century Place: Joe Berusch Shaker Heights High School – Tim Mitchell Third Signs of the Times: Manualism Versus Oralism in Deaf Education Place: Nadia Degeorgia Shaker Heights High School – Tim Mitchell Website – Junior Group Division First The House That George Built Place: Ryan Stimson, Matteo Giovanetti, Marc Giovanetti Saint Barnabas School – Judith Darus Second More Than Just the Bomb : J. -

Cleveland-Visitor OND17.Pdf

$5.00 ClevelandTHINGS TO DO DINING SHOPPING MAPS VisitorOctober, November, December 2017 Museum Unique Our Choice Take 5 Walking Tour Shopping Restaurants David Baker, CEO, Pro Football Hall of Fame Your Guide to the Best Attractions Restaurants Shopping Tours and more! Great Lakes Science Center the most trusted source for visitor information since 1980 cityvisitor.com www.cityvisitor.com Cleveland Visitor 1 CONTENTS Enriching the Visitor Experience in Northeast Ohio since 1980 Rocco A. Di Lillo DEPARTMENTS Chairman Reed McLellan Find the Best Cleveland Has to Offer President/Publisher Looking for fun things to do, unique shopping and delectiable dining spots...then read on. Joe Jancsurak Editor 38 Take 5 with David Baker We Jon Darwal FEATURES caught up with the President and CEO of the Pro Football Hall of Fame, and asked Advertising Consultant 8 University Circle is known for its him to “Take 5” to discuss the Hall and museums, concert hall, and architectural Northeast Ohio Sheila Lopez gems—all in one square mile and just Sales & Marketing Manager four miles east of downtown. And don’t forget to check out its neighbor: Cleve- Jodie McLeod land’s Little Italy. DEPARTMENTS Art Director Things to Do ..................................................6 12 Museum Walk Put on your walking Colleen Gubbini shoes and join us for an enjoyable trek Greater Cleveland Map .........................16 Customer Service through two of Cleveland’s most cultur- Downtown Map ......................................18 ally rich neighborhoods. Where to Eat ...............................................20 Memberships Destination Cleveland; 23 Tremont To gain a true taste of this Dry Cleaners ................................................23 Akron/Summit Convention and eclectic neighborhood, we have just the Weekend Brunch ......................................24 Visitors Bureau; Canton/Stark restaurant for you. -

Experience a Real Departure from Ordinary Shopping! Ohio Station Outlets Is the First and Only Themed Outlet Center in the World

Experience a Real Departure from Ordinary Shopping! Ohio Station Outlets is the first and only themed outlet center in the world. The architecture, history, entertainment, and hand-crafted vintage trains ferrying shoppers throughout the center, combined with the hottest brands in outlet shopping, create an experience tour groups will definitely not want to miss. @ohiostation /ohiostation @ohiostation 1 Quicken Loans Arena Home of the NBA Champion Cleveland Cavaliers Lake Erie 2 Progressive Field Home of the AL Champion CLEVELAND 3 Cleveland Indians 3 Rock and Roll Hall of 1 2 Fame and Museum 5 Mall Hours 4 4 Cleveland Metroparks Zoo Monday-Saturday: 5 Cedar Point 10 a.m. - 9 p.m. 6 Castle Noel 7 Historic Medina Square From Toledo Sunday: Home of AI Root Candle 10 a.m.- 6 p.m. 8 Akron Art Museum 11 From 9 Akron Children’s Museum Youngstown Train Hours 10 Lock 3 Monday-Saturday: Concerts and Attractions 6 7 12 p.m. - 7 p.m. 11 Cuyahoga Valley Scenic AKRON 8 B 9 Sunday: Railroad MEDINA 10 12 p.m. - 5 p.m. 12 Pro Football Hall of Fame LODI C D 13 Amish Country Lodging: To schedule your A Hampton Inn Wooster tour group, contact: BURBANK B Hawthorn Suites 12 Akron/Seville CANTON Barbara Potts C Comfort Inn & Suites A Exit 204 Guest Services Manager Wadsworth From 13 Ohio Station Outlets D Holiday Inn Express & Columbus (330) 948-9929 Suites Wadsworth Ohio Station Outlets • 9911 Avon Lake Road • Burbank, Ohio 44214 • Take I-71 S., Exit 204 • 330-948-1239 Experience..