Regional Maps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bavaria: Statistics 2020

Bavaria: Statistics 2020 www.statistik.bayern.de Publication service The avarian State Office for Statistics issues more than 400 publications annually. The current list of publications is available on the Internet as a file but can also be provided free of charge in printed form. Free of charge Publication service is the download of most publications, All publications are available e. g. statistical reports (PDF or Excel format). on the Internet at www.statistik.bayern.de/produkte Subject to charge are all print versions (also of statistical reports), data carriers and selected files (e. g. of directories, of contributions, of the yearbook). Explanation of symbols Rounding 0 less than half of 1 in the last digit occupied, In general totals have been rounded and therefore but more than zero may not sum. As a result minor deviations from the – no figures or magnitude ero reported totals may occur when individual figures are / no data because the numerical value is not added up. When totals are shown as a percentage, sufficiently reliable the sum of the individual figures may not be 100 due to rounding. In general the sum of percentages is not · numerical value unknown or not to be disclosed made to be 100 . ... data will be available later x cell blocked for logical reasons Abbreviations ( ) limited informational value because the numerical value is of limited statistical reliability € euro p provisional numerical value EU European Union r corrected numerical value ALC association of local councils s estimated numerical value ha hectare (10,000 m2) D average hl hectolitres (100 litres) ‡ corresponds to mill. -

Demographisches Profil Für Den Landkreis Dingolfing-Landau

Beiträge zur Statistik Bayerns, Heft 553 Regionalisierte Bevölkerungsvorausberechnung für Bayern bis 2039 x Demographisches Profil für den xLandkreis Dingolfing-Landau Hrsg. im Dezember 2020 Bestellnr. A182AB 202000 www.statistik.bayern.de/demographie Zeichenerklärung Auf- und Abrunden 0 mehr als nichts, aber weniger als die Hälfte der kleins- Im Allgemeinen ist ohne Rücksicht auf die Endsummen ten in der Tabelle nachgewiesenen Einheit auf- bzw. abgerundet worden. Deshalb können sich bei der Sum mierung von Einzelangaben geringfügige Ab- – nichts vorhanden oder keine Veränderung weichun gen zu den ausgewiesenen Endsummen ergeben. / keine Angaben, da Zahlen nicht sicher genug Bei der Aufglie derung der Gesamtheit in Prozent kann die Summe der Einzel werte wegen Rundens vom Wert 100 % · Zahlenwert unbekannt, geheimzuhalten oder nicht abweichen. Eine Abstimmung auf 100 % erfolgt im Allge- rechenbar meinen nicht. ... Angabe fällt später an X Tabellenfach gesperrt, da Aussage nicht sinnvoll ( ) Nachweis unter dem Vorbehalt, dass der Zahlenwert erhebliche Fehler aufweisen kann p vorläufiges Ergebnis r berichtigtes Ergebnis s geschätztes Ergebnis D Durchschnitt ‡ entspricht Publikationsservice Das Bayerische Landesamt für Statistik veröffentlicht jährlich über 400 Publikationen. Das aktuelle Veröffentlichungsverzeich- nis ist im Internet als Datei verfügbar, kann aber auch als Druckversion kostenlos zugesandt werden. Kostenlos Publikationsservice ist der Download der meisten Veröffentlichungen, z.B. von Alle Veröffentlichungen sind im Internet -

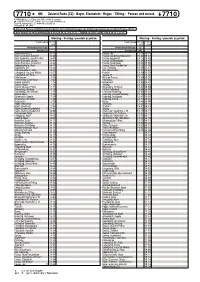

Kursbuch (VU/MB2/FPL KBP) / Renderdll

à ܍ Q Zelezná Ruda (CZ) - Bayer. Eisenstein - Regen - Tittling - Passau und zurück 7710 7710 PROBO BUS a.s., Cihlárská 520, 34401 Domazlice ` +420 379 793 161, E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: www.probo.cz / www.vlp-passau.de Gültig ab 01.04.2016 Zwischen Passau und Hörmannsdorf gelten die Tarifbestimmungen der Verkehrsgemeinschaft Landkreis Passau (VLP). Kein Verkehr an Wochenfeiertagen D und am 24.12. und 31.12. / Nejede ve státni svátky v DE a 24.12. + 31.12. Montag - Freitag / pondeli az pátek Montag - Freitag / pondeli az pátek Fahrtnummer 7710 Fahrtnummer 7710 7710 001 002 004 Verkehrsbeschränkungen Verkehrsbeschränkungen S Anmerkungen Anmerkungen 853 Zelezna Ruda (CZ) 6 32 Passau, Hbf 13 20 15 45 Bayer. Eisenstein, Bahnhof 6 40 Passau, Am Schanzl(Busbucht) 13 22 15 47 Bayer. Eisenstein, Local-Bahn-Mus 6 40 Passau, Eggendobl 13 23 15 48 Bayer. Eisenstein, Schule 6 41 Passau, Sturmbergweg 13 24 15 49 Bayer. Eisenstein, Sonnenhof 6 42 Passau, Bockhofweg 13 25 15 50 Seebachschleife, Abzw 6 47 Passau, Abzw Freudenhain 13 25 15 50 Regenhütte, Ort 6 52 Ries, Rennweg 13 26 15 51 Zwieslerwaldhaus, Abzw 6 54 Ries, Wasserturm 13 27 15 52 Ludwigsthal, Haus zur Wildnis 6 57 Pramöd 13 28 15 53 Ludwigsthal, Gh. Pauli 6 58 Jägerreuth 13 29 15 54 Fällenrechen 7 00 Moos bei Passau 13 30 15 55 Theresienthal, Linke Haus 7 02 Patriching 13 31 15 56 Zwiesel, Bahnhof 7 12 Bäckerreuth 13 32 15 57 Zwiesel, Anger 7 15 Jacking 13 33 15 58 Zwiesel, Brauerei Pfeffer 7 17 Schwaiberg, Gh Bauer 13 37 15 59 Zwieselberg, Siedlung 7 18 Hof bei Tiefenbach 13 38 16 00 Zwieselberg, Info Zentrum 7 20 Lohhof bei Ruderting 13 39 16 02 Dreieck Abzw 7 23 Ruderting, Lohwald-Siedlung 13 40 16 03 Schweinhütt, Kapelle 7 24 Ruderting, Buchbauer 13 41 16 05 Schweinhütt, Gh. -

Die Herkunft Und Bedeutung Des Ortsnamens Regensburg

Albrecht Greule Die Herkunft und Bedeutung des Ortsnamens Regensburg Regensburg liegt am nördlichsten Punkt der Donau. Die Stadt geht auf eine Gründung der Römer zurück, sie ist heute Hauptstadt des bayerischen Regierungsbezirks Oberpfalz, Sitz der Fürsten von Thurn und Taxis, und hat einen berühmten Dom, in dem die Regensburger Domspatzen singen. Ihr Name hat nichts mit dem Regen, der vom Himmel fällt, zu tun, wie oft spaßhaft angenommen wird, sondern mit dem hier in die Donau mündenden Fluss Regen. Der Name des aus Tschechien kommenden Flusses begegnet bereits anno 819 (Kopie 9. Jahrhundert) in einer Traditionsurkunde in althochdeutscher (altbairischer) Gestalt als Regan . Allerdings scheint Regin , lateinisch Reginus , der einzige und ursprüngliche Name für den Fluss Regen gewesen zu sein, und nicht Regan , worin die erste Anspielung des Fluss- und des Stadtnamens auf das Nass vom Himmel (althochdeutsch regan ) fassbar wird. Auch der Name des am Regen gelegenen Stadtteils Reinhausen (1007 Regin-husen ) enthält die ursprüngliche Form des Flussnamens. Obwohl auf der Bauinschrift für das gewaltige Legionslager, das die Römer an der Regen-Mündung 179 n. Chr. errichteten, kein Name verzeich- net ist, wissen wir, dass der gesamte Siedlungskomplex bei den Römern Regino hieß. Sowohl auf einer spätrömischen Straßenkarte als auch im Itinerar des Kaisers Antoninus, die beide im Kern die Verhältnisse des beginnenden 3. Jahrhunderts n. Chr. wiedergeben, ist Regino (= Regensburg) ein- getragen. Was liegt näher als die Annahme, dass die Römer ihr Legionskastell nach dem Fluss be- nannten, an dessen Mündung in die Donau es errichtet worden war. Regino ist ein lateinischer Ab- lativ (Lokativ), der ‘am Regen’ bedeutet. -

Amazing Danube River Cruise with the Bolingbrook Area Chamber of Commerce Offered in Partnership with the West Suburban Chamber of Commerce Executive Group

DISCOVER & EXPLORE AMAZING DANUBE RIVER CRUISE WITH THE BOLINGBROOK AREA CHAMBER OF COMMERCE OFFERED IN PARTNERSHIP WITH THE WEST SUBURBAN CHAMBER OF COMMERCE EXECUTIVE GROUP Act now and save up to BOOK $2,200 PER CABIN &SAVE if deposited by November 1st!* Click here to Cruise the 5-star MS Amadeus Queen BOOK NOW STARTING AT $3,849 PER PERSON w/air & taxes INCLUDES ROUNDTRIP AIRFARE AND BONUS NIGHT IN MUNICH! Departing October 12-21, 2022 Welcome aboard the MS Amadeus Imperial for a 7 night cruise visiting 4 European countries along the Danube. Our ports of call include Budapest, Bratislava, Vienna, Melk and Linz. We have chartered the entire ship and would love to have you join us on our Journey of Discovery as we cruise the Danube. Our cruise is not only a “Memory in the Making” but a great value as well. For additional information or questions please contact: Kevin O’Keeffe at (630) 226-8420 HIGHLIGHTS & PORTS DAY 1 (Oct 12): USA – Munich Depart the USA for Munich today. (in-flight meals) Day 2 (Oct 13): Munich Upon arrival in Munich you will be greeted at the airport and transported to your Munich area hotel. Located at the river Isar in the south of Bavaria, is famous for its beautiful architecture, fine culture, and the annual Oktoberfest beer celebration. Munich’s cultural scene is second to none and the city center appears mostly as it did in the late 1800s. Day 3 (Oct 14): Munich - Passau Today you will enjoy a tour of the city of Munich. -

Standortumfrage 2017 Landkreis Freyung-Grafenau

IHK-Standortumfrage 2017 Landkreis Freyung-Grafenau Meinungsbild zum Wirtschaftsstandort Über 60 Prozent der Betriebe im Land- 83,3 Prozent würden sich wieder für Vereinzelte sehen sich gezwungen, kreis Freyung-Grafenau bewerten ihren Firmensitz entscheiden. ihren Standort zu verlagern, zu ver- ihren Standort mit sehr gut oder gut, In den kommenden drei Jahren kleinern oder aufzugeben. jeder Dritte mit befriedigend. planen 42 Prozent der Befragten Obwohl die Gesamtnote von 2,3 Erweiterungen oder umfangreiche unter dem IHK-Bezirk-Schnitt liegt, Investitionen. Das ist der höchste Wert ist die Standortloyalität sehr hoch: im Niederbayernvergleich. Gesamtnote für den Standort Zufriedenheit nach Noten 2,3 56,2 % ø 32,6 % 7,9 % Regionale Unterschiede 3,3 % 0 % 1 2 3 4 5 Regen Straubing * 2,6 2,1 Freyung- Grafenau Deggendorf 2,3 Nochmalige Standortentscheidung 2,1 Landshut * Dingolfing- 2,1 Landau 2,2 Passau * 83,3 % 16,7 % 2,3 Rottal-Inn ja nein 2,4 * Bezieht sich auf Stadt und Landkreis Entwicklung der letzten drei Jahre Zukünftige Entwicklung 36,7 % 56,7 % 3,3 % 3,3 % 42 % 53,5 % 1,1 % 3,4 % Erweiterung oder um- Keine Veränderung Verkleinerung Verlagerung / Gründung Erweiterung oder um- Keine Veränderung Verkleinerung Verlagerung / Aufgabe fangreiche Investition des Standortes fangreiche Investition des Standortes Standortfaktoren im Überblick Die wichtigsten Faktoren Punkten kann der Landkreis Freyung-Grafenau mit Standortkosten, Energieversorgung und Mitarbeiterloyalität. Loyalität und Motivation der Mitarbeiter Zudem werden das Wohnumfeld und -angebot positiv bewertet. Breitbandversorgung Durch seine Grenznähe und der Lage im Bayerischen Wald hat der Landkreis Nachholbedarf bei der Infrastruktur. Verfügbarkeit von beruflich qualifizierten Fachkräften Unterdurchschnittliche Zufriedenheit besteht mit der Autobahnanbindung. -

Habitat Use and Survival of Gray Partridge Pairs in Bavaria, Germany

National Quail Symposium Proceedings Volume 6 Article 19 2009 Habitat Use and Survival of Gray Partridge Pairs in Bavaria, Germany Wolfgang Kaiser Ilse Storch University of Freiburg John P. Carroll University of Georgia Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/nqsp Recommended Citation Kaiser, Wolfgang; Storch, Ilse; and Carroll, John P. (2009) "Habitat Use and Survival of Gray Partridge Pairs in Bavaria, Germany," National Quail Symposium Proceedings: Vol. 6 , Article 19. Available at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/nqsp/vol6/iss1/19 This Habitat is brought to you for free and open access by Volunteer, Open Access, Library Journals (VOL Journals), published in partnership with The University of Tennessee (UT) University Libraries. This article has been accepted for inclusion in National Quail Symposium Proceedings by an authorized editor. For more information, please visit https://trace.tennessee.edu/nqsp. Kaiser et al.: Habitat Use and Survival of Gray Partridge Pairs in Bavaria, Germ Gray Partridge in Germany Habitat Use and Survival of Gray Partridge Pairs in Bavaria, Germany Wolfgang Kaiser1, Ilse Storch2, John P. Carroll3,4 1Bund Naturschutz Cham, Regen, Germany 2Department of Wildlife Ecology and Management, University of Freiburg, D-79085 Freiburg, Germany 3Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, USA Gray partridge (Perdix perdix) habitat studies have been undertaken in a number of countries but have gen- erally focused on winter and brood rearing. We monitored survival of grey partridge pairs relative to habitat during the breeding season. Our study area was located near Feuchtwangen in north-west Bavaria, Germany. During 1991 to 1994, we used compositional analysis to assess habitat with survival and year as covariates for 38 radio-tagged partridge pairs. -

Landkreis Straubing-Bogen Allgemeiner Sozialdienst (ASD) Anschrift Leutnerstr.15 · 94315 Straubing Telefon: Tel

Informations- und Beratungsstellen (Netzwerk-Partner der Albertus-Schule) Frühkindlicher Bereich Name: Mobile Sonderpädagogische Hilfe (MSH) Anschrift Veit-Höser-Str. 2 · 94327 Bogen Telefon: 09422-50115-124 Email: [email protected] Angebote: Bei Entwicklungsauffälligkeiten bzw. Entwicklungsrisiken in den Bereichen Sprache, Wahrnehmung, Motorik und emotional-soziale Entwicklung. Kinder im Kindergarten- und Vorschulalter. Name: Interdisziplinäre Frühförderstelle Anschrift Hebbelstr. 9 · 94315 Straubing Telefon: 09421/18965-0 Email: [email protected] Träger: KJF Regensburg Angebote: Bei Entwicklungsverzögerung oder Auffälligkeiten in den Bereichen Grob- und Feinmotorik, Sprache, Lernen/ Denken und Wahrnehmung von Kindern im Säuglings-, Kleinkind- und Vorschulalter. Name: Interdisziplinäre Frühförderstelle für Kinder mit Hörbehinderung Anschrift Auf der Platte 11 · 94315 Straubing Telefon: 09421/542-0 Email: frü[email protected] Träger: Bezirk Niederbayern Angebote: Beratung bei Hörschädigung (von Geburt bis Einschulung), Altersgemäße pädagogisch-audiologische Hörprüfung, Individuelle Förderung der kindlichen Entwicklung, Spezifische Angebote für hörende Kinder gehörloser Eltern, etc. Name: Koki – Netzwerk frühe Kindheit Anschrift Leutnerstr. 15 / Zimmer E26 · 94315 Straubing Telefon: 09421/973219 Email: [email protected] Träger: Landratsamt Straubing-Bogen Angebote: Für Schwangere und bei Kindern bis 3 Jahre: Beratung zu allen Fragen rund um „Frühe Kindheit“, Finanzielle Unterstützung für viele Angebote, -

Bayerischer Landtag

Bayerischer Landtag 17. Wahlperiode 16.04.2018 Drucksache 17/19594 Schriftliche Anfrage Antwort der Abgeordneten Jutta Widmann FREIE WÄHLER des Staatsministeriums für Gesundheit und Pflege vom 03.11.2017 vom 05.12.2017 Hebammen und Geburtshilfe in Niederbayern Zu 1.: Die Zahl der freiberuflichen Hebammen und Entbindungs- Ich frage die Staatsregierung: pfleger für die Jahre 2015 und 2016 ist in Anlage 1 darge- stellt. Für das Jahr 2017 liegen noch keine Zahlen vor. 1. Wie viele freiberuflich tätige Hebammen gab es von 2015 bis heute Zu 2.: – in den einzelnen niederbayerischen kreisfreien Städ- Zur Anzahl der Krankenhausgeburten sowie zur Anzahl der ten und Landkreisen? Neugeborenen vergleiche Anlage 2. Die Daten zur Anzahl – nach Jahren? der Krankenhausgeburten für das Jahr 2017 liegen noch nicht vor. 2. Wie hoch war die Zahl der Geburten in den einzelnen Hausgeburten als solche werden statistisch nicht erfasst. niederbayerischen Landkreisen und kreisfreien Städ- Erkenntnisse über die Anzahl der Hausgeburten liegen da- ten im Zeitraum von 2013 bis heute, bitte aufgeschlüs- her nicht vor. selt nach – Geburten im Krankenhaus ? Zu 3.: – Hausgeburten? Die Anzahl der Berufsanfängerinnen und Berufsanfänger ist dem Staatsministerium für Gesundheit und Pflege (StMGP) 3. Wie viele Berufsanfängerinnen gab es bei den Heb- nicht bekannt. Diese sind auch nicht zu erheben: Das ammen in Niederbayern im Zeitraum von 2013 bis Staatsministerium für Bildung und Kultus, Wissenschaft und heute, bitte aufgeschlüsselt nach Kunst (StMBW) verfügt über die Schülerzahlen. Den Regie- – kreisfreien Städten und Landkreisen? rungen ist bekannt, wie viele Personen eine Berufserlaub- – nach Jahren? nis beantragt haben. Diese Personen müssen jedoch nicht zwingend frische Berufsschulabsolventinnen sein. -

Einrichtungen Und Dienste Für Menschen Mit Psychischer Erkrankung Und Suchterkrankung Vorwort

BEZIRK NIEDERBAYERN Sozialverwaltung SEELISCHE GESUNDHEIT Einrichtungen und Dienste für Menschen mit psychischer Erkrankung und Suchterkrankung Vorwort Eine psychische Erkrankung kann uns alle jederzeit treff en. Viele Betroff ene versuchen, ihr Leiden möglichst lange vor ihrem sozialen Umfeld zu verbergen. Schätzungen zufolge bleiben rund zwei Drittel der seelisch erkrankten Menschen unbehandelt. Dies erhöht die Wahr- scheinlichkeit einer Chronifi zierung – bis hin zur dauerhaft en seelischen Behinde- rung. In den vergangenen Jahren ist die gesellschaft liche Stigmatisierung von Menschen mit seelischer Behinderung. psychischen Erkrankungen erfreulicher- Diese Broschüre soll Menschen mit weise zurückgegangen. Gleichzeitig ist psychischer Erkrankung sowie Sucht- die Bereitschaft gestiegen, sich fachge- erkrankung und deren Angehörigen rechte Hilfe zu holen. einen Überblick über Hilfsangebote in An dieser Stelle setzt die Arbeit des Be- Niederbayern verschaff en. zirks Niederbayern als Träger der Ein- Der Bezirk Niederbayern setzt sich dafür gliederungshilfe an, der für die psychia- ein, ein engmaschiges Netz an nieder- trische und teils auch neurologische schwelligen, bedarfsgerechten und Versorgung seiner Bevölkerung zustän- wohnortnahen Hilfen zu gestalten. Als dig ist. Dazu gehören die stationäre und gesamtgesellschaft liche Aufgabe bleibt, teilstationäre Versorgung in den psychia- das Thema psychische Erkrankung bzw. trischen Kliniken und Krankenhäusern Suchterkrankung weiter aus der Tabu- des Bezirks in Mainkofen, Landshut und zone zu holen, um dazu beizutragen, Passau sowie die ambulante Betreuung dass noch mehr Menschen die Hilfen in den dazugehörigen psychiatrischen erhalten, die sie zur Genesung, zum Institutsambulanzen. Darüber hinaus Erhalt der Lebensqualität und zur übernimmt der Bezirk den überwiegen- dauerhaft en Teilhabe am gesellschaft - den Teil der Kosten der sozialpsychia- lichenlichen LebenLebben bbrauchen.rauche trischen Dienste und Suchtberatungs- stellen im Rahmen der ambulanten Eingliederungshilfe. -

Kreisentwicklungs- Konzept 2020 Vielfalt Als Chance – Potenziale Nutzen

Kreisentwicklungs- konzept 2020 Vielfalt als Chance – Potenziale nutzen Landratsamt Rottal-Inn Kreisentwicklung Kreisentwicklungskonzept Landkreis Rottal-Inn Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort .................................................................................................................................. 1 1. Ausgangslage ................................................................................................................ 2 1.1 Zahlen, Daten, Fakten ............................................................................................. 2 1.2 Lokale und regionale Zusammenarbeitsstrukturen und vorhandene Planungen und Konzepte ................................................................................................................. 8 1.3 SWOT-Analyse und Entwicklungsbedarfe ............................................................... 9 2 Der Kreisentwicklungsprozess - Struktur, Ablauf und Bürgermitwirkung ........................21 3 Entwicklungsstrategie ....................................................................................................30 3.1 Vision und Leitbild ..................................................................................................30 3.2 Strategische Handlungsfelder ................................................................................31 3.3 Entwicklungsziele ...................................................................................................32 3.4. Querschnittsthemen ...............................................................................................35 -

![Arxiv:2007.11896V2 [Stat.AP] 3 Aug 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9807/arxiv-2007-11896v2-stat-ap-3-aug-2020-1429807.webp)

Arxiv:2007.11896V2 [Stat.AP] 3 Aug 2020

Causal analysis of Covid-19 spread in Germany Atalanti A. Mastakouri Department of Empirical Inference Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems Tübingen, Germany [email protected] Bernhard Schölkopf Department of Empirical Inference Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems Tübingen, Germany [email protected] Abstract In this work, we study the causal relations among German regions in terms of the spread of Covid-19 since the beginning of the pandemic, taking into account the restriction policies that were applied by the different federal states. We propose and prove a new theorem for a causal feature selection method for time series data, robust to latent confounders, which we subsequently apply on Covid-19 case numbers. We present findings about the spread of the virus in Germany and the causal impact of restriction measures, discussing the role of various policies in containing the spread. Since our results are based on rather limited target time series (only the numbers of reported cases), care should be exercised in interpreting them. However, it is encouraging that already such limited data seems to contain causal signals. This suggests that as more data becomes available, our causal approach may contribute towards meaningful causal analysis of political interventions on the development of Covid-19, and thus also towards the development of rational and data-driven methodologies for choosing interventions. 1 Introduction arXiv:2007.11896v2 [stat.AP] 3 Aug 2020 The ongoing outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic has rendered the tracking of the virus spread a problem of major importance, in order to better understand the role of the demographics and of political measures taken to contain the virus.