UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Playing Along Infinite Rivers: Alternative Readings of a Malay State a Dissertation Submitted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Collecting the People: Textualizing Epics in Philippine History from the Sixteenth Century to the Twenty-First Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/61q8p086 Author Reilly, Brandon Joseph Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Collecting the People: Textualizing Epics in Philippine History from the Sixteenth Century to the Twenty-First A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Brandon Joseph Reilly 2013 © Copyright by Brandon Joseph Reilly 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Collecting the People: Textualizing Epics in Philippine History from the Sixteenth Century to the Twenty-First by Brandon Joseph Reilly Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Michael Salman, Chair My dissertation, “Collecting the People: Textualizing Epics in Philippine History from the Sixteenth Century to the Twenty-First,” examines the study and uses of oral epics in the Philippines from the late 1500s to the present. State institutions and cultural activists uphold epics linked to the pre-colonial era as the most culturally authentic, ancient, and distinctive form of Filipino literature. These “epics” originated as oral traditions performed by culturally diverse groups. Before they could be read, they had to be written down and translated into, first, the colonial language of Spanish, and later, the national languages of English and Filipino. Beginning from the earliest Spanish colonial times, I examine the longer history of writing about, describing, summarizing, and beginning in the late nineteenth century, transcribing the diverse sorts of oral narratives that only in the twentieth century came to be called epics. -

Hajj and the Malayan Experience, 1860S–1941

KEMANUSIAAN Vol. 21, No. 2, (2014), 79–98 Hajj and the Malayan Experience, 1860s–1941 AIZA MASLAN @ BAHARUDIN Universiti Sains Malaysia, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia [email protected] Abstract. Contrary to popular belief, the hajj is a high-risk undertaking for both pilgrims and administrators. For the Malay states, the most vexing problem for people from the mid-nineteenth century until the Second World War was the spread of epidemics that resulted from passenger overcrowding on pilgrim ships. This had been a major issue in Europe since the 1860s, when the international community associated the hajj with the outbreak and spread of infectious diseases. Accusations were directed at various parties, including the colonial administration in the Straits Settlements and the British administration in the Malay states. This article focuses on epidemics and overcrowding on pilgrim ships and the resultant pressure on the British, who were concerned that the issue could pose a threat to their political position, especially when the Muslim community in the Malay states had become increasingly exposed to reformist ideas from the Middle East following the First World War. Keywords and phrases: Malays, hajj, epidemics, British administration, Straits Settlements, Malay states Introduction As with health and education, the colonial powers had to handle religion with great care. The colonisers covertly used these three aspects not only to gain the hearts of the colonised but, more importantly, to maintain their reputation among other colonial powers. Roy MacLeod, for example, sees the introduction of Western medicine to colonised countries as functioning as both cultural agency and western expansion (MacLeod and Lewis 1988; Chee 1982). -

Annualrepeng II.Pdf

ANNUAL REPORT – 2007-2008 For about six decades the Directorate of Advertising and on key national sectors. Visual Publicity (DAVP) has been the primary multi-media advertising agency for the Govt. of India. It caters to the Important Activities communication needs of almost all Central ministries/ During the year, the important activities of DAVP departments and autonomous bodies and provides them included:- a single window cost effective service. It informs and educates the people, both rural and urban, about the (i) Announcement of New Advertisement Policy for nd Government’s policies and programmes and motivates print media effective from 2 October, 2007. them to participate in development activities, through the (ii) Designing and running a unique mobile train medium of advertising in press, electronic media, exhibition called ‘Azadi Express’, displaying 150 exhibitions and outdoor publicity tools. years of India’s history – from the first war of Independence in 1857 to present. DAVP reaches out to the people through different means of communication such as press advertisements, print (iii) Multi-media publicity campaign on Bharat Nirman. material, audio-visual programmes, outdoor publicity and (iv) A special table calendar to pay tribute to the exhibitions. Some of the major thrust areas of DAVP’s freedom fighters on the occasion of 150 years of advertising and publicity are national integration and India’s first war of Independence. communal harmony, rural development programmes, (v) Multimedia publicity campaign on Minority Rights health and family welfare, AIDS awareness, empowerment & special programme on Minority Development. of women, upliftment of girl child, consumer awareness, literacy, employment generation, income tax, defence, DAVP continued to digitalize its operations. -

The Development Continuum: Change and Modernity in the Gayo Highlands of Sumatra, Indonesia a Thesis Presented to the Faculty Of

The Development Continuum: Change and Modernity in the Gayo Highlands of Sumatra, Indonesia A thesis presented to the faculty of the Center for International Studies of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Matthew J. Minarchek June 2009 ©2009 Matthew J. Minarchek. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled The Development Continuum: Change and Modernity in the Gayo Highlands of Sumatra, Indonesia by MATTHEW J. MINARCHEK has been approved for the Center for International Studies by Gene Ammarell Associate Professor of Sociology and Anthropology Gene Ammarell Director, Southeast Asian Studies Daniel Weiner Executive Director, Center for International Studies 3 ABSTRACT MINARCHEK, MATTHEW J., M.A., June 2009, Southeast Asian Studies The Development Continuum: Change and Modernity in the Gayo Highlands of Sumatra, Indonesia (110 pp.) Director of Thesis: Gene Ammarell This thesis provides a 'current history' of development in the village of Aih Nuso in Gunung Leuser National Park, Sumatra, Indonesia. Development in the Leuser region began in the late 1800s whenthe Dutch colonial regime implemented large-scale agriculture and conservation projects in the rural communities. These continued into the 1980s and 1990s as the New Order government continued the work of the colonial regime. The top-down model of development used by the state was heavily criticized, prompting a move towards community-based participatory development in the later 1990s. This thesis examines the most recent NGO-led development project, a micro- hydro electricity system, in the village of Aih Nuso to elucidate the following: 1) The social, economic, and political impacts of the project on the community. -

Firearm Upgrades” Below)

Sample file Gunslinger Adept Marksman When you choose this archetype at 3rd level, you Most warriors and combat specialists spend their learn to perform powerful trick shots to disable or years perfecting the classic arts of swordplay, damage your opponents using your firearms. archery, or polearm tactics. Whether duelist or Trick Shots. You learn two trick shots of infantry, martial weapons were seemingly perfected your choice, which are detailed under "Trick Shots" long ago, and the true challenge is to master them. below. Once per turn, when you make an attack with However, some minds couldn't stop with the a firearm as part of the Attack action, you can apply innovation of the crossbow. Experimentation with one of your trick shots to that attack. Unless alchemical components and rare metals have otherwise noted, you must declare a trick shot before unlocked the secrets of controlled explosive force. the attack roll is made. You learn an additional trick The few who survive these trials of ingenuity may shot of your choice at 7th, 10th, 15th, and 18th level. become the first to create, and deftly wield, firearms. Grit. You have 3 grit points. You gain This archetype focuses on the ability to another grit point at 7th level and one more at 15th design, craft, and utilize powerful, yet dangerous, level. You regain 1 expended grit point each time you ranged weapons. Through creative innovation and roll a 20 on the d20 roll for an attack with a firearm, immaculate aim, you become a distant force of death or reduce a creature of challenge rating ⅛ or higher on the battlefield. -

Conceptual Understanding of Myths and Legends in Malay History

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UKM Journal Article Repository Conceptual Understanding of MythsSari 26 and (2008) Legends 91 - in 110 Malay History 91 Conceptual Understanding of Myths and Legends in Malay History HUSSAIN OTHMAN ABSTRAK Teks-teks sejarah Melayu juga kaya dengan cerita dongeng and legenda. Tetapi, banyak sarjana yang mengkaji isi teks itu kerap membuat tanggapan yang salah. Dalam kajian mereka, mereka menetapkan aspek luaran, dan bukannya aspek fungsi dan sejarah pada cerita mitos dan legenda itu. Oleh itu, adalah tujuan rencana ini untuk menerokai pemahaman konsep saya tentang cerita legenda dan mitos dalam teks sejarah klasik Melayu untuk membuktikan adanya kebenaran sejarah yang tersirat di sebalik cerita itu. Untuk tujuan itu, saya telah memilih Sejarah Melayu, Hikayat Raja-Raja Pasai dan Hikayat Merong Mahawanga. Kata kunci: Kosmologi Melayu, Sejarah Melayu, simbol Melayu, tafsir dan ta’wil ABSTRACT Malay historical texts are also rich in the mythical and legendary stories. Unfortunately, many scholars who study the content of the texts have always misunderstood them. In their study, they specify on the superficial aspects, instead of functional and historical aspects of the mythical and legendary stories. It is the purpose of this paper to explore my conceptual understanding of mythological and legendary stories in the Malay classical historical texts to prove that there are indeed historical truth embedded within these stories. To do that, Sejarah Melayu, Hikayat Raja-raja Pasai and Hikayat Merong Mahawangsa are selected. Key words: Malay cosmology, Malay history, Malay symbols, tafsir and ta’wil INTRODUCTION Much has been said about the symbols used and adored by man in ancient times. -

Breakthrough

BREAKTHROUGH April 16, 2005 - April 16, 2009 3 9I<8BK?IFL>? BREAKTHROUGH Thousands of Paths toward Resolution THE EXECUTING AGENCY OF REHABILITATION AND RECONSTRUCTION FOR ACEH AND NIAS (BRR NAD–NIAS) April 16, 2005 - April 16, 2009 Head Office Nias Representative Office Jakarta Representative Office Jl. Ir. Muhammad Thaher No. 20 Jl. Pelud Binaka KM. 6,6 Jl. Galuh ll No. 4, Kabayoran Baru Lueng Bata, Banda Aceh Ds. Fodo, Kec. Gunungsitoli Jakarta Selatan Indonesia, 23247 Nias, Indonesia, 22815 Indonesia, 12110 Telp. +62‑651‑636666 Telp. +62‑639‑22848 Telp. +62‑21‑7254750 Fax. +62‑651‑637777 Fax. +62‑639‑22035 Fax. +62‑21‑7221570 www.e‑aceh‑nias.org know.brr.go.id Advisor : Kuntoro Mangkusubroto Photography : Arif Ariadi Author : Eddy Purwanto Bodi Chandra Editor : Cendrawati Suhartono (Coordinator) Graphic Design : Bobby Haryanto (Chief) Gita Widya Laksmini Soerjoatmodjo Edi Wahyono Margaret Agusta (Chief) Priscilla Astrini Wasito Copy Editor : Ihsan Abdul Salam Final Reviewer : Aichida Ul‑Aflaha Writer : Eddie Darajat Heru Prasetyo Erwin Fahmi Maggy Horhoruw Intan Kencana Dewi Ratna Pawitra Trihadji Ita Fatia Nadia Ricky Sugiarto (Chief) Jamil Gunawan Teuku Roli Ilhamsyah Nur Aishyah Usman Waladi Nur Akbar Raden Pamekas Saifullah Abdulgani Syafiq Hasyim Vika Oktavia Yacob Ishadamy English Translation Editor : Linda Hollands Copy Editor : Margaret Agusta Translator : T. Ferdiansyah Thajib Oei Eng Goan Development of the BRR Book Series is supported by Multi Donor Fund (MDF) through United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Technical Assistance to BRR Project ISBN 978‑602‑8199‑49‑0 With this BRR Book Series, the Indonesian government, its people, and BRR wish to express their deep gratitude for the many kind helping hands extended from all over the world following the December 26, 2004 earthquake and tsunami in Aceh and the March 28, 2005 earthquake in the islands of Nias. -

Developing a Waldorf Curriculum in Asia

Freie Hochschule Stuttgart Developing a Waldorf Curriculum in Asia Written Scientific Master’s Thesis for obtaining the academic degree Master of Arts Class- and Subject Teacher for Waldorf Schools Submitted by: Serene Fong Email Address: [email protected] Date: 24 November 2017 Supervisor: Martyn Rawson Course Leader: Iris Taggert 1 Acknowledgments There are many people around the world to whom I am immensely grateful: My supervisor Martyn Rawson for his guiding help, perceptive insights, razor-sharp and witty explanations and observations that broadened my perspectives and challenged me to improve; Horst Hellman, for hours of insightful discussions, and providing an inspiring and living example of a constantly striving teacher and mentor; Iris Taggert, for constant encouragement, support and guidance; The numerous teachers and mentors who have shared their rich experiences and insights through lengthly interviews, particularly Neil Boland, Gilbert van Kerckhoven, Andrew Hill, Ursula Nicolai, Monika Di Donato, and Eugene Schwartz; All the warm and helpful teachers who responded to the survey and queries; My generous lecturers and classmates in the International Master’s Course for helping me in numerous ways, for translating and sharing their story resources, especially Zhang Shu Chun, Ianinta Sembiring, Kim So Young, Kaori Seki Kohchi, and Ji Young Park; Rosemarie Harrison, my very encouraging and supportive friend and proofreader; My teachers and friends, and all who contributed to this project in some way or other; Finally, to my family, and my mother, who have supported and encouraged me every step of the way; to Ho Pan Liang, my husband, confidante, classmate, and colleague, for walking with and helping me on this journey, and my two lovely children for their patience and love, and for many happy hours together enjoying stories from around the world. -

An Examination of Flintlock Components at Fort St. Joseph (20BE23), Niles, Michigan

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 4-2019 An Examination of Flintlock Components at Fort St. Joseph (20BE23), Niles, Michigan Kevin Paul Jones Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Kevin Paul, "An Examination of Flintlock Components at Fort St. Joseph (20BE23), Niles, Michigan" (2019). Master's Theses. 4313. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/4313 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN EXAMINATION OF FLINTLOCK COMPONENTS AT FORT ST. JOSEPH (20BE23), NILES, MICHIGAN by Kevin P. Jones A thesis submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Anthropology Western Michigan University April 2019 Thesis Committee: Michael S. Nassaney, Ph.D., Chair José A. Brandão, Ph.D. Amy S. Roache-Fedchenko, Ph.D. Copyright by Kevin P Jones 2019 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want to thank my Mom and Dad for everything they do, have done, and will do to help me succeed. Thanks to my brothers and sister for so often leading by example. Also to Rod Watson, Ihsan Muqtadir, Shabani Mohamed Kariburyo, and Vinay Gavirangaswamy – friends who ask the tough questions, like “are you done yet?” I want to thank advisers and supporters from past and present. Dr. Kory Cooper, for setting me out on this path; Kathy Atwell for providing me an opportunity to start; my professors and advisers for this project for allowing it to happen; and Lauretta Eisenbach for making things happen. -

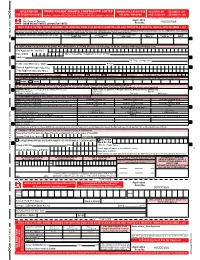

Bsence of the Cancelled Cheque, Our Company May Reject the Application Or It May Consider the Bank Details As Given on the Application Form at Its Sole Discretion

APPLICATION FORM INDIAN RAILWAY FINANCE CORPORATION LIMITED COMMON APPLICATION FORM ISSUE OPENS ON : DECEMBER 8, 2015 (A Government of India Enterprise) (FOR RESIDENT APPLICANTS) Credit Rating : “CRISIL AAA / Stable” by CRISIL Limited, “[ICRA] AAA” by ICRA Limited, “CARE AAA” by CARE Limited FOR ASBA / NON ASBA ISSUE CLOSES ON* : DECEMBER 21, 2015 To, *For early closure or extension of the issue, refer overleaf Application The Board of Directors, 90000568 INDIAN RAILWAY FINANCE CORPORATION LIMITED Form No. PUBLIC ISSUE OF TAX FREE, SECURED, REDEEMABLE, NON-CONVERTIBLE BONDS IN THE NATURE OF DEBENTURES VIDE SHELF PROSPECTUS & PROSPECTUS TRANCHE I DATED DECEMBER 2, 2015 I/we hereby confirm that I/we have read and understood the terms and conditions of this Application Form and the attached Abridged Prospectus and agree to the ‘Applicant’s Undertaking’ as given overleaf. I/we hereby confirm that I/we have read the instructions for filling up the Application Form given overleaf. TEAR HERE LEAD MANAGER/ CONSORTIUM / TRADING MEMBER STAMP & CODE SUB- CONSORTIUM MEMBER /BROKER’S SUB BROKER/AGENT ESCROW BANK / SCSB BRANCH BANK BRANCH REGISTRAR’S / SCSB DATE OF STAMP & CODE CODE STAMP & CODE SERIAL NO. SERIAL NO. RECEIPT 1. APPLICANT’S DETAILS - PLEASE FILL IN BLOCK LETTERS (Please refer to page 16 of the attached Abridged Prospectus) First Applicant (Mr./ Ms./M/s.) Date of Birth D D M M Y Y Y Y Name of Guardian (if applicant is minor) Mr./Ms. Address Pin Code (Compulsory) Tel No. (with STD Code) / Mobile Email Second Applicant (Mr./ Ms./M/s.) Third Applicant (Mr./ Ms./M/s.) 2. -

Download Download

https://doi.org/10.47548/ijistra.2020.23 Vol. 1, No. 1, (October, 2020) Penguasaan maritim dan aktiviti perdagangan antarabangsa kerajaan-kerajaan Melayu Maritime control and international trade activities of Malay kingdoms Ahmad Jelani Halimi (PhD) ABSTRAK Kapal dan pelaut Melayu merupakan antara yang terbaik dalam kegiatan KATA KUNCI maritim tradisional dunia. Ia telah wujud lebih lama daripada mereka yang perahu, pelaut, lebih dipopularkan dalam bidang ini – Phoenicians, Greek, Rom, Arab dan perdagangan, juga Vikings. Ketika masyarakat benua sibuk mencipta pelbagai kenderaan di maritim, darat dengan penciptaan roda, masyarakat Melayu sudah boleh Nusantara menyeberang laut dengan perahu-perahu mereka. Sejak air laut meningkat kesan daripada pencairan ais di kutub dan glesiar di benua, sekitar 10,000- 6,000 tahun yang lampau, orang Melayu telah mula memikirkan alat pengangkutan mereka lantaran mereka telah terkepung di pulau-pulau akibat kenaikan paras laut dan tenggelamnya Benua Sunda. Justeru terciptalah pelbagai jenis perahu dan alat pengangkutan air yang dapat membantu pergerakan mereka. Sejak zaman itu, orang Melayu telah mampu menguasai laut sekitarnya. Ketika orang-orang Phoenician dan Mesir baru pandai berbahtera di pesisir laut tertutup Mediterranean dan Sungai Nil, orang Melayu telah melayari samudra luas; Teluk Benggala, Lautan Hindi dan Lautan Pasifik. Sekitar abad ke-2SM perahu-perahu Melayu yang besar-besar telah berlabuh di pantai timur India dan tenggara China, sementara masyarakat bertamadun tinggi lain baru sahaja pandai mencipta perahu-perahu sungai dan pesisir. Pada mulanya perahu-perahu Melayu hanya digunakan untuk memberi perkhidmatan pengangkutan hinggalah masuk abad ke-4 apabila komoditi tempatan Nusantara mula mendapat permintaan di peringkat perdagangan antarabangsa. Pelbagai jenis rempah ratus, hasil hutan dan logam diangkut oleh perahu-perahu itu untuk menyertai perdagangan dunia yang sedang berkembang. -

Kajian Terhadap Gambaran Jenis Senjata Orang Melayu Dalam Manuskrip Tuhfat Al-Nafis

BAB 1 PENGENALAN ______________________________________________________________________ 1.1 Latar Belakang Masalah Kajian 1.1.1 Peperangan Dunia seringkali diancam dengan pergaduhan dan peperangan, sama ada peperangan antarabangsa, negara, agama, etnik, suku kaum, bahkan wujud juga peperangan yang berlaku antara anak-beranak dan kaum keluarga. Perang yang di maksudkan adalah satu pertempuran ataupun dalam erti kata lain merupakan perjuangan (jihad). Kenyataan ini turut di perakui oleh Sun Tzu dalam karyanya yang menyatakan bahawa peperangan itu adalah urusan negara yang penting untuk menentukan kelangsungan hidup atau kemusnahan sesebuah negara, maka setiap jenis peperangan itu perlu diselidiki terlebih dahulu matlamatnya.1 Di samping itu, perang juga sering dianggap oleh sekalian manusia bahawa ia merupakan satu perbalahan yang melibatkan penggunaan senjata sehingga mampu mengancam nyawa antara sesama umat manusia.2 Ini menunjukkan bahawa penggunaan senjata merupakan elemen penting dalam sebuah peperangan. Perang merupakan salah satu daripada kegiatan manusia kerana ia meliputi pelbagai sudut kehidupan. Peredaran zaman serta berkembangnya sesebuah tamadun telah menuntut seluruh daya upaya manusia untuk berjuang mempertahankan negara terutamanya dalam peperangan. Ini kerana pada masa kini perang merupakan satu 1 Saputra, Lyndon, (2002), Sun Tzu the Art of Warfare, Batam : Lucky Publisher, hlmn 8 2 Kamus Dewan Bahasa (Edisi Keempat), (2007), Kuala Lumpur : Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka , hlmn 1178 masalah yang sangat besar, rumit dalam sebuah