LAOS Executive Summary the Constitution and Some Laws And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mineral Industry of Laos in 2015

2015 Minerals Yearbook LAOS [ADVANCE RELEASE] U.S. Department of the Interior October 2018 U.S. Geological Survey The Mineral Industry of Laos By Yolanda Fong-Sam In 2015, Laos produced a variety of mineral commodities, oversees and implements the mineral law, mine safety, and including barite, copper, gold, iron ore, lead, and silver. mine closure regulations; creates the necessary regulations and Laos had a variety of undeveloped mineral resources. The guidelines for the promotion of the mining and metallurgical Government recognized mining as a critical sector of the sector; and issues, rejects, extends, and withdraws mining economy, and it continued to support it while at the same time licenses (Department of Mineral Resources of Thailand, 2013; promoting other domestic and foreign investments. As of 2014, REDD Desk, The, 2015; Ministry of Natural Resources and employment in the mining sector was about 15,381 people, Environment, 2016). which represented about 0.3% of the total population of Laos. In 2015, the main producers of copper and gold in Laos were Lane Xang Minerals Ltd. (MMG LXML), which was Minerals in the National Economy a subsidiary of MMG Ltd. of Hong Kong (90% interest) and the Government (10% interest), and Phu Bia Mining Ltd. In 2015, Lao’s industrial sector, which included the (PBM), which was a subsidiary of PanAust Ltd. of Australia construction, electricity generation, manufacturing, and mining (90% interest) and the Government (10% interest). The and quarrying sectors, grew by 9.7% and contributed 29.3% to country’s major mineral industry facilities and their capacities Lao’s real gross domestic product (GDP) (at constant 2002 are listed in table 2. -

Executive Summary, Oudomxay Province

Executive Summary, Oudomxay Province Oudomxay Province is in the heart of northern Laos. It borders China to the north, Phongsaly Province to the northeast, Luang Prabang Province to the east and southeast, Xayabouly Province to the south and southwest, Bokeo Province to the west, and Luang Namtha Province to the northwest. Covering an area of 15,370 km2 (5,930 sq. ml), the province’s topography is mountainous, between 300 and 1,800 metres (980-5,910 ft.) above sea level. Annual rain fall ranges from 1,900 to 2,600 millimetres (75-102 in.). The average winter temperature is 18 C, while during summer months the temperature can climb above 30 C. Muang Xai is the capital of Oudomxay. It is connected to Luang Prabang by Route 1. Oudomxay Airport is about 10-minute on foot from Muang Xai center. Lao Airlines flies from this airport to Vientiane Capital three times a week. Oudomxay is rich in natural resources. Approximately 60 rivers flow through its territory, offering great potential for hydropower development. About 12% of Oudomxay’s forests are primary forests, while 48% are secondary forests. Deposits of salt, bronze, zinc, antimony, coal, kaolin, and iron have been found in the province. In 2011, Oudomxay’s total population was 307,065 people, nearly half of it was females. There are 14 different ethnic groups living in the province. Due to its mountainous terrains, the majority of Oudomxay residents practice slash- and-burn agriculture, growing mountain rice. Other main crops include cassava, corn, cotton, fruits, peanut, soybean, sugarcane, vegetables, tea, and tobacco. -

Ethnic Group Development Plan LAO: Northern Rural Infrastructure

Ethnic Group Development Plan Project Number: 42203 May 2016 LAO: Northern Rural Infrastructure Development Sector Project - Additional Financing Prepared by Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry for the Asian Development Bank. This ethnic group development plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Ethnic Group Development Plan Nam Beng Irrigation Subproject Tai Lue Village, Lao PDR TABLE OF CONTENTS Topics Page LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND TERMS v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A10-1 A. Introduction A10-1 B. The Nam Beng Irrigation Subproject A10-1 C. Ethnic Groups in the Subproject Areas A10-2 D. Socio-Economic Status A10-2 a. Land Issues A10-3 b. Language Issues A10-3 c. Gender Issues A10-3 d. Social Health Issues A10-4 E. Potential Benefits and Negative Impacts of the Subproject A10-4 F. Consultation and Disclosure A10-5 G. Monitoring A10-5 1. BACKGROUND INFORMATION A10-6 1.1 Objectives of the Ethnic Groups Development Plan A10-6 1.2 The Northern Rural Infrastructure Development Sector Project A10-6 (NRIDSP) 1.3 The Nam Beng Irrigation Subproject A10-6 2. -

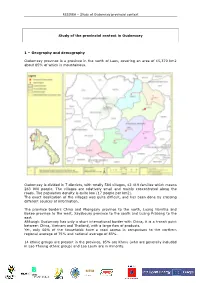

Study of the Provincial Context in Oudomxay 1

RESIREA – Study of Oudomxay provincial context Study of the provincial context in Oudomxay 1 – Geography and demography Oudomxay province is a province in the north of Laos, covering an area of 15,370 km2 about 85% of which is mountainous. Oudomxay is divided in 7 districts, with totally 584 villages, 42 419 families which means 263 000 people. The villages are relatively small and mainly concentrated along the roads. The population density is quite low (17 people per km2). The exact localization of the villages was quite difficult, and has been done by crossing different sources of information. The province borders China and Phongsaly province to the north, Luang Namtha and Bokeo province to the west, Xayaboury province to the south and Luang Prabang to the east. Although Oudomxay has only a short international border with China, it is a transit point between China, Vietnam and Thailand, with a large flow of products. Yet, only 66% of the households have a road access in comparison to the northern regional average of 75% and national average of 83%. 14 ethnic groups are present in the province, 85% are Khmu (who are generally included in Lao Theung ethnic group) and Lao Loum are in minority. MEM Lao PDR RESIREA – Study of Oudomxay provincial context 2- Agriculture and local development The main agricultural crop practiced in Oudomxay provinces is corn, especially located in Houn district. Oudomxay is the second province in terms of corn production: 84 900 tons in 2006, for an area of 20 935 ha. These figures have increased a lot within the last few years. -

Market Chain Assessments

Sustainable Rural Infrastructure and Watershed Management Sector Project (RRP LAO 50236) Market Chain Assessments February 2019 Lao People’s Democratic Republic Sustainable Rural Infrastructure and Watershed Management Sector Project Sustainable Rural Infrastructure and Watershed Management Sector Project (RRP LAO 50236) CONTENTS Page I. HOUAPHAN VEGETABLE MARKET CONNECTION 1 A. Introduction 1 B. Ban Poua Irrigation Scheme 1 C. Markets 1 D. Market Connections 4 E. Cross cutting issues 8 F. Conclusion 9 G. Opportunity and Gaps 10 II. XIANGKHOUANG CROP MARKETS 10 A. Introduction 10 B. Markets 11 C. Conclusion 17 D. Gaps and Opportunities 17 III. LOUANGPHABANG CROP MARKET 18 A. Introduction 18 B. Markets 18 C. Market connections 20 D. Cross Cutting Issues 22 E. Conclusion 23 F. Opportunities and Gaps 23 IV. XAIGNABOULI CROP MARKETS 24 A. Introduction 24 B. Market 24 C. Market Connection 25 D. Conclusion 28 E. Opportunities and Gaps 28 V. XIANGKHOUANG (PHOUSAN) TEA MARKET 29 A. Introduction 29 B. Xiangkhouang Tea 30 C. Tea Production in Laos 30 D. Tea Markets 31 E. Xiangkhouang Tea Market connection 33 F. Institutional Issues 38 G. Cross Cutting Issues 41 H. Conclusion 41 I. Opportunities and Gaps 42 VI. XIANGKHOUANG CATTLE MARKET CONNECTION ANALYSIS 43 A. Introduction 43 B. Markets 43 C. Export markets 44 D. Market Connections 46 E. Traders 49 F. Vietnamese Traders 49 G. Slaughterhouses and Butchers 50 H. Value Creation 50 I. Business Relationships 50 J. Logistics and Infrastructure 50 K. Quality – Assurance and Maintenance 50 L. Institutions 50 M. Resources 51 N. Cross Cutting Issues 51 O. Conclusion 51 P. -

Shifting Cultivation in Laos: Transitions in Policy and Perspective

Shifting Cultivation in Laos: Transitions in Policy and Perspective This report has been commissioned by the Secretariat of the Sector Working Group For Agriculture and Rural Development (SWG-ARD) and was written by Miles Kenney-Lazar Graduate School of Geography, Clark University, USA [email protected] The views contained in this report are those of the researcher and may not necessary reflect those of the Government of Lao PDR 1 Abbreviations and acronyms ACF Action Contre la Faim CCAFS Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security CGIAR Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research CPI Committee for Planning and Investment DAEC Department of Agricultural Extension and Cooperatives DCCDM Department of Climate Change and Disaster Management DAFO District Agriculture and Forestry Office DLUP Department of Land Use Planning EC European Commission FS 2020 Forest Strategy to the Year 2020 GOL Government of Laos ha hectares IIED International Institute for Environment and Development Lao PDR Lao People‘s Democratic Republic LFAP Land and Forest Allocation Program LPRP Lao People‘s Revolutionary Party MAF Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry MONRE Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment MPI Ministry of Planning and Investment NAFRI National Agriculture and Forestry Research Institute NA National Assembly NEM New Economic Mechanism NLMA National Land Management Authority NGPES National Growth and Poverty Eradication Strategy NNT NPA Nakai-Nam Theun National Protected Area NPEP National Poverty Eradication Program NTFPs -

Sin City: Illegal Wildlife Trade in Laos' Special Economic Zone

SIN CITY Illegal wildlife trade in Laos’ Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS CONTENTS This report was written by the Environmental Investigation Agency. 2 INTRODUCTION Special thanks to Education for Nature Vietnam (ENV), the Rufford Foundation, Ernest Kleinwort 3 PROFILE OF THE GOLDEN TRIANGLE SPECIAL Charitable Trust, Save Wild Tigers and Michael Vickers. ECONOMIC ZONE & KINGS ROMANS GROUP Report design by: 5 WILDLIFE TRADE AT THE GT SEZ www.designsolutions.me.uk March 2015 7 REGIONAL WILDLIFE CRIME HOTSPOTS All images © EIA/ENV unless otherwise stated. 9 ILLEGAL WILDLIFE SUPERMARKET 11 LAWLESSNESS IN THE GOLDEN TRIANGLE SPECIAL ECONOMIC ZONE 13 WILDLIFE CLEARING HOUSE: LAOS’ ROLE IN REGIONAL AND GLOBAL WILDLIFE TRADE 16 CORRUPTION & A LACK OF CAPACITY 17 DEMAND DRIVERS OF TIGER TRADE IN LAOS 19 CONCLUSIONS 20 RECOMMENDATIONS ENVIRONMENTAL INVESTIGATION AGENCY (EIA) 62/63 Upper Street, London N1 0NY, UK Tel: +44 (0) 20 7354 7960 Fax: +44 (0) 20 7354 7961 email: [email protected] www.eia-international.org EIA US P.O.Box 53343 Washington DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 483 6621 Fax: +202 986 8626 email: [email protected] COVER IMAGE: © Monkey Business Images | Dreamstime.com 1 INTRODUCTION This report takes a journey to a dark corner of north-west Lao PDR (hereafter referred to as Laos), in the heart of the Golden Triangle in South-East Asia. The Environmental Investigation While Laos’ wildlife laws are weak, there The blatant illegal wildlife trade by Agency (EIA) and Education for Nature is not even a pretence of enforcement in Chinese companies in this part of Laos Vietnam (ENV) have documented how the GT SEZ. -

The Mineral Industry of Laos in 2016

2016 Minerals Yearbook LAOS [ADVANCE RELEASE] U.S. Department of the Interior January 2020 U.S. Geological Survey The Mineral Industry of Laos By Yolanda Fong-Sam In 2016, the production of mineral commodities—notably References Cited copper, gold, and tin—represented a minor part of the economy Arion Legal Lao PDR Lawyers, 2017, Update on the revision of Lao Law of Laos. The legislative framework for the mineral sector on Minerals: Vientiane, Laos, Arion Legal Lao PDR Lawyers, June 16. in Laos is provided by the Law on Minerals No. 02/NA of (Accessed December 22, 2017, at http://arionlegal.la/update-on-the-revision- December 20, 2011 (Lao PDR Trade Portal, 2012; Arion Legal of-the-law-on-minerals/.) Lao PDR Lawyers, 2017). Data on mineral production are in Lao PDR Trade Portal, 2012, Law on Minerals (revised version) No. 02/NA: Vientiane, Laos, Ministry of Industry and Commerce, Department of Import table 1. Table 2 is a list of major mineral industry facilities. and Export. (Accessed December 22, 2017, at http://www.laotradeportal.gov.la/ More-extensive coverage of the mineral industry of Laos index.php?r=site/display&id=602.) can be found in previous editions of the U.S. Geological Survey Minerals Yearbook, volume III, Area Reports— International—Asia and the Pacific, which are available at https://www.usgs.gov/centers/nmic/asia-and-pacific. TABLE 1 LAOS: PRODUCTION OF MINERAL COMMODITIES1 (Metric tons, gross weight, unless otherwise noted) Commodity2 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 METALS Antimony, mine production, Sb content 521 804 620 -

District Population Projections

Ministry of Planning and Investment Lao Statistics Bureau District Population Projections Supported By: United Nations Population Fund Vientiane Capital, September 2019 District Population Projections Committees 2015-2035 Steering Committee 1. Mr Samaichan Boupha, Head of the Lao Statistics Bureau, Vice Minister of Planning and Investment 2. Ms Phonesaly Souksavath, Deputy Head of the Lao Statistics Bureau Technical Committee 1. Ms Thilakha Chanthalanouvong, General Director of Social Statistics Department, Lao Statistics Bureau 2. Ms Phoungmala Lasasy, Deputy Head of Register Statistics Division, Social Statistics Department Projection Committee 1. Mr Bounpan Inthavongthong, Technical Staff, Register Statistics Division, Social Statistics Department Supported By: United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) District Population Projections 2015-2035 I Forward Population projections are extremely important for effective management and administration of population growth and related demographic issues. If population projections are as accurate as possible, the government and policy makers will be informed to formulate policies and develop plans with greater precision in order to provide necessary and effective population services such as social services and social welfare. Due to this importance and necessity the Lao Statistics Bureau, under the Ministry of Planning and Investment has conducted this population projection by using the baseline data from the fourth Population and Housing Census in 2015. Population projections demonstrate a calculation of the population’s size and characteristics in the future. It is not possible to guarantee one hundred percent accurate estimations, even if the best available methodology was utilized in the estimation. Therefore, it is necessary for Lao Statistics Bureau to improve the population projections periodically in order to obtain a more accurate picture of the population in the future, which is estimated using data from several surveys such as Lao Social Indicator Survey and other surveys. -

42203-025: Northern Rural Infrastructure Development Sector

Indigenous Peoples Plan February 2021 LAO: Northern Rural Infrastructure Development Sector Project – Additional Financing Prepared by the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry for the Asian Development Bank. This indigenous peoples plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Ethnic Group Development Plan Nam Tin 2 PRI Subproject List of Abbreviations ADB : Asian Development Bank AF : Additional Financing CDO : Community Development Officer DAFO : District Agriculture and Forestry Office DCO : District Coordination Office DLWU : District Lao Women’s Union DMU : District Management Unit DOI : Department of Irrigation DOP : Department of Planning EA : Executing Agency EGDF : Ethnic Group Development Framework EGDP : Ethnic Group Development Plan EIA : Environmental Impact Assessment EIRR : Economic Internal Rate of Return EMP : Environmental Management Plan FS : Feasibility Study FHH : Female-Headed Household FPG : Farmers’ Production Group GAP : Gender Action Plan GIC : Grant Implementation Consultant GOL : Government of Lao PDR HH : -

Lao PDR Gender Integration Development Study Draft Final Report

Lao PDR Gender Integration Development Study Draft Final Report March 2019 Lao PDR Gender Integration Development Study Draft Final Report March 2019 Gender Integration Study Lao PDR Tel +942 6680 Lao PDR Gender Integration Study Draft Final Report Contents Amendment Record This report has been issued and amended as follows: Issue Revision Description Date Approved by 2 cwt Edits Mar 27 cwt [Gender Integration Study Report] Contents 1 Background and Introduction 11 1.1 The Forest Carbon Partnership Facility 11 1.2 Proposed Emissions Reduction Program 13 1.3 GID Study Methodology 15 2 The Study Area 17 2.1 Demographic Characteristics of Rural Households 17 2.2 Land Allocation in Selected ER-P Villages 22 2.3 Problematic Land Access, Use and Control Issues 23 2.4 Rural Households in the ER-P Provinces 25 2.5 The Changing Face of Land Use 26 2.6 Role of Livestock Development, Gender and Ethnic Equality and Human Nutrition 30 2.7 Changing Forest Landscape and its Importance 30 2.8 Non-Timber Forest Products 31 2.9 Household Dependency on Forestry 32 2.10 Loss of Agricultural and Forest Land 35 2.11 Understanding of REDD+ 37 2.12 Young Women Seeking Alternatives 40 2.13 The Green Climate Fund 44 3 Policy, Political and Institutional Support for Gender Issues 47 3.1 Policy 47 4 Priorities of Women in the ER-P Villages 49 4.1 Priorities 49 4.2 Action Plan for Gender Integration for the ER-P 50 4.3 Conclusions 57 5 Bibliography and Appendix 60 5.1 Bibliography 60 5.2 Appendix 61 Tables Table 1 Consultations with Ethnic Minority Groups ............................... -

The Mineral Industry of Laos in 2010

2010 Minerals Yearbook LAOS U.S. Department of the Interior August 2012 U.S. Geological Survey THE MINERAL INDUSTRY OF LAOS By Yolanda Fong-Sam In 2010, Laos produced a variety of mineral commodities. Commodity Review These included tin, copper concentrate, silver, and gold, of which production increased by 46%, 26%, 7.2%, and 0.6% Metals respectively, compared with that of 2009 (table 1). In April, the country began operating the Nam Theun 2 Bauxite and Alumina.—The Laos Bolaven Plateau bauxite dam, which is the largest hydroelectric dam in the country. project, which is located in the southern part of the country, was The project was a joint venture of the Government of Laos, being developed by Sino Australian Resources (Laos) Co., Ltd. the Electricity Generating Public Co. of Thailand, and the (SARCO), which was a joint venture between China Nonferrous French energy company Électricité de France. The dam is Metals Industry’s Foreign Engineering and Construction Co., located in central Laos in the Nam Theun River and was built Ltd. of China (51%) and ORD River Resources Ltd. of Australia at a cost of $1.3 billion, which was funded in part by the Asian (49%). SARCO had two tenements in the property; they were Development Bank and the World Bank. The majority (95%) of the LSI tenement, which covers a 66-square-kilometer (km²) the generated power was exported to neighboring Thailand, and area, and the Yuqida tenement, which covers a 42-km² area the remaining 5% was consumed locally, which met 20% of the (ORD River Resources Ltd., 2010a, p.