Lochries 0516 Sml.Pdf (3.572Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bridgeness Distance Slab

SHORTER NOTES | 519 Bridgenese Th s distance slab Joanna Close-Brooks* The Roman distance slab from Bridgeness at the eastern end of the Antonine Wall, found in 1868 bees ,ha n repeatedly published recentls ha d yan , been discusse detaidn i Phillipy lb s (1974) and Keppie (1979). The slab has been displayed in the National Museum since its discovery. In the winter of 1979/80 it was taken down from the wall of the Roman gallery and cleaned and e Museum'repaire th e stafl f th o f y b d s Conservation Laboratory unde e directioth r f Miso n s Mary MacQueen preparation i display, w ne a r . nfo Washin accumulatee gth d dusgrimd an t e frostone frone th m th f e o t revealed faint traces of red paint in parts of the carving, traces which now appear pink, and which showed up most clearly whe stone wetpainns traced th e confinere e wa .Th f tar s o specifido t c areas particulan i , r letterine incisee th th o t d dgan grooves definin pelte gth a ornamen eitheo tt inscriptione r sidth f eo . left-hane th n I d panel paind beheadere , e nece tth see e th tracef kb o n nn o e dsca th Britot a d nan s severehi bas f o ed head alsd an o, curiousl groove th n i ye formin divisioe gth n betweee th n bottom horseman' e edgth f eo horseright-hans e bace shi th cloath f n ko I .d kan d pane paind lre t seee b nsoldiecloae n e onlth th ca f kn o y o r farthes righe th to tt agains aedicula,e pillae th tth f ro and in this case the entire cloak appears to have been painted red. -

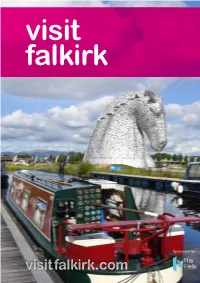

2020 Visit Falkirk Area Guide

visit falkirk Sponsored by visitfalkirk.com Welcome to Falkirk, Scotland! The Falkirk area sits at the very heart of Scotland, midway between Edinburgh and Glasgow with excellent motorway and rail links and two international airports close by. Falkirk is home to two of the world’s Heritage most unique attractions which are The Falkirk area is rich in history, with World transforming the Scottish landscape: Heritage UNESCO site the Antonine Wall, • The Falkirk Wheel including Rough Castle, one of the best preserved Roman Forts; baronial mansion • The Helix Park ‘Home of the Kelpies’ 5 star Callendar House, home to a working The Falkirk area is also home to a great Georgian Kitchen; the Falkirk Trinity Church range of further attractions including; & the Faw Kirk Graveyard including the Tomb the historic Callendar House and Park, of Sir John de Graeme (William Wallace’s right a large section of the John Muir Way, hand man); The Steeple; Dunmore Pineapple; the Antonine Wall (a UNESCO World Kinneil House and Museum featuring Heritage Site), Bo’ness & Kinneil excellent examples of renaissance art; The Hippodrome in Bo’ness; 4 star Bo’ness & Railway, Blackness Castle, Museum of Kinneil Railway a working steam railway Scottish Railways, Kinneil House and including Scotland’s largest Railway museum; Museum and much much more. and the ship that never sailed Blackness Why not Visit Falkirk today? Castle. Immerse yourself in 2000 years of heritage. Further details on the Falkirk area and attractions can be found in this leafet, at www.visitfalkirk.com or you can follow us on Facebook, Twitter @Vfalkirk, Instagram and YouTube. -

The Antonine Wall

FRONTIERS OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE WORLD HERITAGE SITE THE ANTONINE WALL Management Plan 2014-19 CONSULTATION REPORT & SEA STATEMENT CONSULTATION REPORT & SEA STATEMENT THE ANTONINE WALL CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 1. Introduction 3 1.1 Background to the consultation 1.1 Background to the consultation 3 A consultative draft of the Antonine Wall Management Plan 2014-19 was issued for public consultation on 1.2 The consultation 4 1 April 2013, remaining open for 12 weeks, until 1.3 Report objectives 4 28 June 2013. Both the consultation draft and the final 1.4 The approach to consultation 5 Management Plan can be found on this webpage: www.historic-scotland.gov.uk 1.5 Analysis of consultation responses 5 The draft Management Plan was developed jointly by 2. How have views and information the six Partners: East Dunbartonshire Council, Falkirk been taken into account? 6 Council, Glasgow City Council, Historic Scotland, North 2.1 Introduction 6 Lanarkshire Council, and West Dunbartonshire Council. 2.2 What options were considered It sets out the long-term (30-year) vision for the and how were they identified? 6 management of the Antonine Wall which is then 2.3 What environmental effects were refined into a series of key objectives for a five-year predicted by the SEA? 7 period. These objectives seek to both build on the achievements of the first five-year Management Plan 2.4 What were the views on the (2008-12) and to lay the foundations for further Management Plan as a whole development in the one that will follow. -

Exploring Scotland's World Heritage Sites Leaflet

The Forth Bridge Skara Brae Village Bay. Photographer: Lorne Gill New Kilpatrick Cemetery Exploring Scotland’s World The Forth Bridge St Kilda The Forth Bridge represents the pinnacle of 19th-century bridge One hundred miles off the west coast of Scotland the clear Atlantic Heritage construction and is without doubt the world’s greatest cantilever waters of the St Kilda archipelago supports a diverse and stunning trussed bridge. When opened in 1890 it had the longest bridge range of animals and plants, several unique to the islands. Its cliffs spans in the world, a record held for 27 years. It was also the world’s and sea stacks are home to the largest colony of seabirds in Europe, Sites first major steel structure, and today remains a potent symbol of including gannets and puffins; its waters contain remarkable marine Britain’s industrial, scientific, architectural and transport heritage. communities, while the wild Soay sheep trace their ancestry back The bridge forms a unique milestone in the evolution of bridge and thousands of years. other steel construction, is innovative in its design, its concept, its materials and in its enormous scale. It marks a landmark event in the Despite the remoteness of the islands and their harsh environment, application of science to architecture. It remains a working estuary people lived and farmed there for millennia. They caught seabirds crossing, and today is busier than ever. for food, feathers and oil, grew some crops and kept livestock. Well-preserved remains of this human occupation can be seen on Spectacular views of the Forth Bridge can be gained from historic the main island of Hirta and the smaller islands. -

Planning Performance Framework 2020

PLANNING PERFORMANCE FRAMEWORK Planning and Building Standards Service July 2020 Planning Performance Framework Foreword Welcome to the annual Planning community needs and ensuring the health important step forward this year with the Performance Framework which outlines and well-being of our teams. It has been Council agreeing to purchase the site and our performance, showcases our good to see how the team has reacted, the submission of the Planning in Principle achievements and improvements in with many pragmatic measures being application which will allow this 63 hectare 2019- 20. taken forward and a clear commitment site to be remediated and developed, part to continue to provide a service in very of our City Deal project. Last year’s Planning Performance difficult and challenging times. Framework was peer reviewed by The Place and Design Panel continues to Edinburgh City Council who are part of Before the pandemic, development be recognised nationally and has become our Solace Benchmarking Group. Officers interest in West Dunbartonshire was high embedded in the planning process in from Edinburgh City Council visited the with the first phase of the Dumbarton West Dunbartonshire. In September, we Council in January 2020 to share good waterfront path being opened for use. co-hosted an event - Place and Design: practice and they indicated that there is Queens Quay continues to progress with Interventions to Create Successful Places a strong sense of collaborative working the waterfront path now constructed, the with over 70 delegates from the public within the planning service, which created spine road through the site complete and and private sectors to share insight a good team ethos where sharing the care home and the energy centre and experience of these interventions. -

The Antonine Wall Interpretation Plan and Access Strategy

FRONTIERS OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE WORLD HERITAGE SITE THE ANTONINE WALL Interpretation Plan and Access Strategy INTERPRETATION PLAN & Access Strategy March 2014 The Antonine Wall 2 Interpretation Plan & Access Strategy Contents ____________________________________________________________________ 1. Background and Context 3 1.1 Introduction 3 1.2 Current Situation 3 1.3 Key Issues 4 1.4 Other Challenges 6 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2. Access Strategy 9 2.1 Background 9 2.2 Current Audiences 13 2.3 Non-attenders 17 2.4 Barriers to Access 18 2.5 Methods for Overcoming Barriers to Access 25 2.6 Target Audiences 31 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3. Meeting Visitor Expectations 34 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 4. Significance of the Antonine Wall 36 4.1 Statement of Outstanding Universal Value 36 4.2 Significance 36 4.3 Contemporary values 37 4.4 Tangible and Intangible Heritage 38 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 5. Interpretive Objectives 42 5.1 Knowledge and Understanding 42 5.2 Skills 42 5.3 Enjoyment, Inspiration and Creativity 42 5.4 Attitude and Values 42 5.5 Activity, Behaviour and Progression 42 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Historic Environment Strategy for Falkirk 2018

Our Future in the Past Historic Environment Strategy for Falkirk 2018 A NE FOR A' Contents Historic Environment Strategy for Falkirk 2018 Contents Foreword 01 Executive Summary 03 1. Introduction 05 1.1 The Historic Environment of Falkirk 1.2 Statutory Designations 1.3 Non - Statutory Designations 2. Why is a new Strategy Required? 11 2.1 Making Better Places 2.2 Changing Context 3. Benefits of the Historic Environment 13 3.1 Well-being 3.2 Cultural identity 3.3 Economic benefit 3.4 Tourism 4. Policy Context 17 4.1 National Framework 4.2 Local Context 5. Achievements 19 5.1 Improved Sense of Place and Co-ordinated Attention to the Historic Environment 5.2 Townscape Heritage Initiatives 5.3 The Falkirk Townscape Heritage Initiative 5.4 Other Local Achievements 5.5 Antonine Wall Frontiers of the Roman Empire World Heritage Site 5.6 Falkirk : Landscape, Industry and Work 6. Challenges 27 6.1 Shrinking Resources 6.2 Deteriorating Condition and Erosion 6.3 Energy Efficiency 6.4 Shortage of Traditional Building Skills and Materials 6.5 Climate Change 7. Opportunities 31 7.1 Funding Sources 7.2 Heritage Network 8. Strategic Vision and Themes 33 8.1 Vision for Historic Environment of Falkirk 8.2 Themes 8.3 Priority Actions 8.4 Action Plan 9. Monitoring Performance 45 9.1 Measuring Success 9.2 Reviewing Progress 10. Further Information Sources 47 10.1 Links to Planning Policies, Supplementary Guidance, Conservation Area Appraisals and Management Plans 10.2 Links to Sites and Monument Record and HES Designations 10.3 Falkirk’s Buildings at Risk 10.4 THI Community Engagement Programme 2013 - 2018 10.5 Local Trails and Information Panels 10.6 Funding Sources Foreword 01 Foreword Our area has a fantastically interesting and varied historic environment consisting of many different kinds of historic artefacts, sites and buildings; many of these Battle of Falkirk Muir Heritage Trail sites and buildings are nationally important. -

Free Visitor Map Inside!

free visitor map inside! WELCOME to Falkirk, Scotland! The Falkirk area sits at the very heart of Scotland, midway between Edinburgh and Glasgow with excellent motorway and rail links and two international airports close by. Falkirk is home to two of the world’s most unique attractions which are transforming the Scottish landscape: • The Falkirk Wheel • The Kelpies in Helix Park The Falkirk area is also home to a great range of further attractions including; the historic Callendar House and Park, a large section of the John Muir Way, the Antonine Wall (a UNESCO World Heritage Site), Bo’ness and Kinneil Steam Railway, Blackness Castle, Kinneil House and Museum and much much more. Why not Visit Falkirk today? Further details on the Falkirk area and attractions can be found in this leaflet, at www.visitfalkirk.com or you can follow us on Facebook and Twitter. The Kelpies The Falkirk Wheel The Helix The Helix has transformed 350 hectares in Falkirk into a brand new recreational green space and visitor attraction, including lagoon, wetlands, splash play area, trails and outdoor event space. The jewel within this project,The Kelpies, stand 30 metres tall, and are the world’s largest equine sculptures. Towering over the Forth & Clyde canal, they form a dramatic gateway to the canal entrance on the East Coast of Scotland. Visitors can experience a tour inside The Kelpies and hear all about their origin and inspiration. The Kelpie visitor centre and gift shop opens in 2015. The Falkirk Wheel Scotland’s most exciting example of 21st century engineering, The Falkirk Wheel, is the World’s first rotating boatlift and eye-catching working sculpture which links the Forth & Clyde Canal with the Union Canal. -

The Antonine Wall Management Plan 2014-19

FRONTIERS OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE WORLD HERITAGE SITE THE ANTONINE WALL Management Plan 2014-19 FRONTIERS OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE WORLD HERITAGE SITE THE ANTONINE WALL Management Plan 2014-19 COVER: Rough Castle © Crown Copyright: RCAHMS Unless otherwise specified, images are © Crown Copyright reproduced courtesy of Historic Scotland. www.historicscotlandimages.gov.uk FOREWORD by Ms Fiona Hyslop, MSP, Cabinet Secretary for Culture and External Affairs This new five year Management Plan seeks to capitalise and build on previous work, and I am delighted to see that benefits for local, national and international communities continue to be prioritised. The Antonine Wall is a site that has a presence on the international stage as part of a serial transnational World Heritage Site. It represents the outward looking nature of heritage work in Scotland. There are valuable opportunities to be grasped, particularly in the areas of learning, tourism and research. Strong partnership In 2008, when the Antonine Wall was nominated as working around best practice approaches to site part of the Frontiers of the Roman Empire World management and conservation are being developed by Heritage Site, a Management Plan was drafted as part the Partners and I look forward to seeing this partnership of the UNESCO requirements. This set out some of the approach developing further over the next five years. key management concerns for the first five years of This Management Plan includes many actions inscription, and laid the groundwork for the requested by local groups, community councils and development of the international partnership model others following a wide public consultation exercise. -

Walking Through Social Research. London: Routledge. Listening Walks

Forthcoming in: Bates, C. and Rhys-Taylor, A. (eds.) (2017) Walking Through Social Research. London: Routledge. Listening walks: A method of multiplicity Dr Michael Gallagher, Manchester Metropolitan University Dr Jonathan Prior, Cardiff University Abstract A listening walk is a mode of walking in which listening to the sounds of spaces is the focus. In this chapter, we look at the potential of listening walks to act as a research method and pedagogic tool. We emphasise its flexibility and adaptability for different purposes and research topics. To make this argument, we consider a listening walk led by one of the authors in Edinburgh, Scotland. We demonstrate that, while listening walks have been posited as a means of producing research data about perceived soundscape quality, they also provide us with an endlessly repeatable and adaptable method that can address a much broader range of research questions, and can be embedded within a variety of teaching settings. Keywords listening, sound, soundwalk, soundscape, multi-sensory, pedagogy, Edinburgh, Brussels, multiplicity, audio 1 Author biographies Michael Gallagher is a research fellow in the Faculty of Education at Manchester Metropolitan University. His works spans human geography and childhood studies, with a particular interests in sound, media and experimental methods. Documentation of his research can be found at: http://www.michaelgallagher.co.uk Jonathan Prior is a lecturer in human geography in the School of Geography and Planning at Cardiff University. His research interests span environmental and landscape policy making and sonic geography. Within the latter area, he is working on ways in which geographers can better attend to the sonic components of environments. -

The Antonine Wall Research to Inform an Education Strategy

The Antonine Wall Towards an Education strategy The Antonine Wall Research to Inform an Education Strategy Commissioned by Historic Scotland 1 The Antonine Wall Towards an Education strategy Contents Executive Summary 3 1.0 Introduction 6 2.0 Methodology 8 3.0 Review of the Literature 10 4.0 Results of the audit 14 5.0 Consultation with schools 22 6.0 Further and Higher Education 35 7.0 Community learning and special interest groups 38 8.0 Triggers and Barriers 45 9.0 Examples of good practice 47 10.0 Detailed Recommendations 50 11.0 Identification of additional funding resources 53 12.0 Appendices 55 2 The Antonine Wall Towards an Education strategy Executive Summary Aim and Objectives The aim of this report is to provide recommendations to Historic Scotland (HS) and partners on the development of an Education Strategy for The Antonine Wall (TAW)and its component sites. The key objectives in our research were to establish what education resources connected to TAW currently exist, who holds them, who uses them and how; to establish what is currently being delivered by way of education programmes connected to TAW, by whom and for whom; to establish to what extent engagement with TAW is currently seen to be successful in supporting learning and teaching in communities, for special interest groups etc. and to identify other ways in which these non-formal education groups would like to engage with the Wall; to establish how engagement with TAW does already, and could further, support studies in the formal education sector, outlining educational -

The Antonine Wall World Heritage Site: a Short Guide

Frontiers Of The Roman Empire: The Antonine Wall World Heritage Site A Short Guide April 2019 NIO M O UN IM D R T IA A L • P • W L O A I R D L D N H O E M R I E TA IN G O E • PATRIM United Nations Frontiers of the Educational, Scientific and Roman Empire Cultural Organization inscribed on the World Heritage List in 2005 A Short Guide April 2019 A Short Guide April 2019 Contents Introduction This short guide is an introduction to the Frontiers of the Roman Empire: Antonine Wall (FRE:AW) World Heritage Site (WHS), its inscription on the World Heritage List, and its management and governance. It is one of a series of Site-specific short guides for each of Scotland’s six WHS. Introduction 1 For information outlining what World Heritage status is and what it means, the responsibilities SHETLAND Antonine Wall: Key Facts 2 and benefits attendant upon achieving World Heritage status, and current approaches The World Heritage Site and Buffer Zone 3 to protection and management see the World Heritage in Scotland short guide. See Further Information and Contacts Statement of Outstanding Universal Value 5 ORKNEY for more information. 1 Kirkwall Managing the Antonine Wall 6 Planning and the Antonine Wall 9 Western Isles Stornoway Further Information and Contacts 10 St kilda 2 Inverness Aberdeen World Heritage Sites in Scotland Perth KEY: 1 Heart of Neolithic Orkney Forth Bridge 6 5 3 2 St Kilda Edinburgh Glasgow 3 FRONTIERS OF THE ROMAN 4 EMPIRE: ANTONINE WALL 4 New Lanark 5 Old and New Towns of Edinburgh 6 Forth Bridge Cover image: The Antonine Wall at Bar Hill looking towards Croy Hill.