Criminal Procedure -- the Potential Defendant's Right to a Speedy Trial, 48 N.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Studying the Exclusionary Rule in Search and Seizure Dallin H

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. Reprinted for private circulation from THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LAW REVIEW Vol. 37, No.4, Summer 1970 Copyright 1970 by the University of Chicago l'RINTED IN U .soA. Studying the Exclusionary Rule in Search and Seizure Dallin H. OakS;- The exclusionary rule makes evidence inadmissible in court if law enforcement officers obtained it by means forbidden by the Constitu tion, by statute or by court rules. The United States Supreme Court currently enforces an exclusionary rule in state and federal criminal, proceedings as to four major types of violations: searches and seizures that violate the fourth amendment, confessions obtained in violation of the fifth and' sixth amendments, identification testimony obtained in violation of these amendments, and evidence obtained by methods so shocking that its use would violate the due process clause.1 The ex clusionary rule is the Supreme Court's sole technique for enforcing t Professor of Law, The University of Chicago; Executive Director-Designate, The American Bar Foundation. This study was financed by a three-month grant from the National Institute of Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice of the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration of the United States Department of Justice. The fact that the National Institute fur nished financial support to this study does not necessarily indicate the concurrence of the Institute in the statements or conclusions in this article_ Many individuals assisted the author in this study. Colleagues Hans Zeisel and Franklin Zimring gave valuable guidance on analysis, methodology and presentation. Colleagues Walter J. -

The “Radical” Notion of the Presumption of Innocence

EXECUTIVE SESSION ON THE FUTURE OF JUSTICE POLICY THE “RADICAL” MAY 2020 Tracey Meares, NOTION OF THE Justice Collaboratory, Yale University Arthur Rizer, PRESUMPTION R Street Institute OF INNOCENCE The Square One Project aims to incubate new thinking on our response to crime, promote more effective strategies, and contribute to a new narrative of justice in America. Learn more about the Square One Project at squareonejustice.org The Executive Session was created with support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation as part of the Safety and Justice Challenge, which seeks to reduce over-incarceration by changing the way America thinks about and uses jails. 04 08 14 INTRODUCTION THE CURRENT STATE OF WHY DOES THE PRETRIAL DETENTION PRESUMPTION OF INNOCENCE MATTER? 18 24 29 THE IMPACT OF WHEN IS PRETRIAL WHERE DO WE GO FROM PRETRIAL DETENTION DETENTION HERE? ALTERNATIVES APPROPRIATE? TO AND SAFEGUARDS AROUND PRETRIAL DETENTION 33 35 37 CONCLUSION ENDNOTES REFERENCES 41 41 42 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AUTHOR NOTE MEMBERS OF THE EXECUTIVE SESSION ON THE FUTURE OF JUSTICE POLICY 04 THE ‘RADICAL’ NOTION OF THE PRESUMPTION OF INNOCENCE “It was the smell of [] death, it was the death of a person’s hope, it was the death of a person’s ability to live the American dream.” That is how Dr. Nneka Jones Tapia described the Cook County Jail where she served as the institution’s warden (from May 2015 to March 2018). This is where we must begin. EXECUTIVE SESSION ON THE FUTURE OF JUSTICE POLICY 05 THE ‘RADICAL’ NOTION OF THE PRESUMPTION OF INNOCENCE Any discussion of pretrial detention must Let’s not forget that Kalief Browder spent acknowledge that we subject citizens— three years of his life in Rikers, held on presumed innocent of the crimes with probable cause that he had stolen a backpack which they are charged—to something containing money, a credit card, and an iPod that resembles death. -

A Critique of Two Arguments Against the Exclusionary Rule: the Historical Error and the Comparative Myth, 32 Wash

Washington and Lee Law Review Volume 32 | Issue 4 Article 4 Fall 9-1-1975 A Critique Of Two Arguments Against The Exclusionary Rule: The iH storical Error And The Comparative Myth Donald E. Wilkes, Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Donald E. Wilkes, Jr., A Critique Of Two Arguments Against The Exclusionary Rule: The Historical Error And The Comparative Myth, 32 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 881 (1975), https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr/vol32/iss4/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington and Lee Law Review at Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington and Lee Law Review by an authorized editor of Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Critique of Two Arguments Against the Exclusionary Rule: The Historical Error and The Comparative Myth DONALD E. WILKES, JR.* Introduction "The great body of the law of evidence consists of rules that oper- ate to exclude relevant evidence."' The most controversial of these rules are those which prevent the admission of probative evidence because of the irregular manner in which the evidence was obtained. Depending on whether the method of obtaining violated a provision of positive law, irregularly obtained evidence' may be separated into two classes. Evidence obtained by methods which meet legal requirements but contravene some moral or ethical principle is un- fairly obtained evidence. -

Terrorism, Miranda, and Related Matters

Terrorism, Miranda, and Related Matters Charles Doyle Senior Specialist in American Public Law April 24, 2013 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41252 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Terrorism, Miranda, and Related Matters Summary The Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution provides in part that “No person ... shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” In Miranda v. Arizona, the Supreme Court declared that statements of an accused, given during a custodial interrogation, could not be introduced in evidence in criminal proceedings against him, unless he were first advised of his rights and waived them. In Dickerson v. United States, the Court held that the Miranda exclusionary rule was constitutionally grounded and could not be replaced by a statutory provision making all voluntary confessions admissible. In New York v. Quarles, the Court recognized a “limited” “public safety” exception to Miranda, but has not defined the exception further. The lower federal courts have construed the exception narrowly in cases involving unwarned statements concerning the location of a weapon possibly at hand at the time of an arrest. The Supreme Court has yet to decide to what extent Miranda applies to custodial interrogations conducted overseas. The lower federal courts have held that the failure of foreign law enforcement officials to provide Miranda warnings prior to interrogation does not preclude use of any resulting statement in a subsequent U.S. criminal trial, unless interrogation was a joint venture of U.S. -

Demanding a Speedy Trial: Re-Evaluating the Assertion Factor in the Baker V

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 67 Issue 1 Article 12 2016 Demanding a Speedy Trial: Re-Evaluating the Assertion Factor in the Baker v. Wingo Test Seth Osnowitz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Seth Osnowitz, Demanding a Speedy Trial: Re-Evaluating the Assertion Factor in the Baker v. Wingo Test, 67 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 273 (2016) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol67/iss1/12 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 67·Issue 1·2016 Demanding a Speedy Trial: Re-Evaluating the Assertion Factor in the Barker v. Wingo Test Contents Introduction .................................................................................. 273 I. Background and Policy of Sixth Amendment Right to Speedy Trial .......................................................................... 275 A. History of Speedy Trial Jurisprudence ............................................ 276 B. Policy Considerations and the “Demand-Waiver Rule”..................... 279 II. The Barker Test and Defendants’ Assertion of the Right to a Speedy Trial .................................................................. 282 A. Rejection of the -

Speedy Trial

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 68 Article 7 Issue 4 December Winter 1977 Speedy Trial Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Speedy Trial, 68 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 543 (1977) This Criminal Law is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAW & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 68, No. 4 Copyright @ 1977 by Northwestern University School of Law Printed in U.S.A. SPEEDY TRIAL United States v. Lovasco, 97 S. Ct. 2044 (1977). The Supreme Court of the United States has v. Marion,7 the Supreme Court focused on the recognized that the right to a speedy trial "is language of the sixth amendment8 and con- one of the most basic rights preserved by our cluded that the sixth amendment speedy trial Constitution."' The right, as encompassed by provision does not apply until an individual the sixth amendment to the United States Con- becomes an accused, that is either through stitution,2 can be traced to the Magna Carta of arrest or indictment. The Court also stated 1215,3 which states, "we will sell to no man, we that Rule 48(b) of the Federal Rules of Criminal will not deny or defer to any man either justice Procedure9 is limited in application to post- or right. -

The Unruly Exclusionary Rule

Marquette Law Review Volume 78 Article 3 Issue 1 Fall 1994 The nrU uly Exclusionary Rule: Heeding Justice Blackmun's Call to Examine the Rule in Light of Changing Judicial Understanding About Its Effects Outside the Courtroom Harry M. Caldwell Carol A. Chase Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Harry M. Caldwell and Carol A. Chase, The Unruly Exclusionary Rule: Heeding Justice Blackmun's Call to Examine the Rule in Light of Changing Judicial Understanding About Its Effects Outside the Courtroom, 78 Marq. L. Rev. 45 (1994). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol78/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE UNRULY EXCLUSIONARY RULE: HEEDING JUSTICE BLACKMUN'S CALL TO EXAMINE THE RULE IN LIGHT OF, CHANGING JUDICIAL UNDERSTANDING ABOUT ITS EFFECTS OUTSIDE THE COURTROOM HARRY M. CALDWELL* CAROL A. CHASE** I. INTRODUCTION There is a war raging in the hearts and minds of most Americans over the efficacy of the American Criminal Justice system. Americans are concerned with rising crime and they sense that the criminal justice sys- tem is not adequately protecting them from crime or criminals. If pressed to identify a focal point of criticism of the justice system, many would name the Exclusionary Rule. The Rule is popularly believed to exclude even the most damning evidence for the slightest police error. -

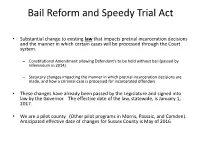

Bail Reform and Speedy Trial Act

Bail Reform and Speedy Trial Act • Substantial change to existing law that impacts pretrial incarceration decisions and the manner in which certain cases will be processed through the Court system. – Constitutional Amendment allowing Defendant’s to be held without bail (passed by referendum in 2014) – Statutory changes impacting the manner in which pretrial incarceration decisions are made, and how a criminal case is processed for incarcerated offenders • These changes have already been passed by the Legislature and signed into law by the Governor. The effective date of the law, statewide, is January 1, 2017. • We are a pilot county. (Other pilot programs in Morris, Passaic, and Camden). Anticipated effective date of changes for Sussex County is May of 2016. Current Processing of a Criminal Case ARREST/CHARGE SUMMONS WARRANT Central Judicial 1st Appearance/Bail AP not Processing Review (within 72 AP is present Hours) present Plea Hearing Case Resolved Early Case Not Resolved Grand Jury Disposition Presentation Conference Sentencing Arraignment Conference Status Conference Pre-Trial Conference Trial Aspects of Existing System That Will Change • Under the current system, the SCPO is not required, and does not, have an AP present at CJP Court. − CJP Court currently sits 1 day per week and is in session for about 4 hours • Under the current system, for defendants remanded to the jail on a warrant, no weekend appearance is necessary. − This is so because the first appearance/bail review does not need to take place for 72 hours. − Therefore, for a defendant arrested on a Friday, we can legally wait until Monday for the first appearance/bail review Aspects of Existing System That Will Change (Continued) • Under the current system, there are no lengthy testimonial hearings prior to the EDC conference. -

1.4 Sources of Law

1.4 Sources of Law Below is a brief summary of the sources of law for addressing racial disparities in North Carolina criminal cases. These sources are discussed in greater detail in the applicable chapters of this manual. Equal Protection. As long ago as 1891, the U.S Supreme Court recognized that under the Fourteenth Amendment, “no state can deprive particular persons or classes of persons of equal and impartial justice under the law.”91 The Equal Protection Clause has been the subject of numerous interpretations in the intervening years. As one scholar observed, however, it was “[n]ot until the last decade of the Warren Court,” when heightened scrutiny became law, “[that] the equal protection clause evolve[d] from a largely moribund constitutional provision to a potent egalitarian instrument.”92 Today, the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment is an important source of rights for defendants challenging unequal treatment in the criminal justice system. It may be relied on by defendants challenging practices such as selective policing based on race,93 selective prosecution based on race,94 discrimination in the pretrial release setting,95 racially biased jury selection procedures,96 racially biased grand jury foreperson selection procedures,97 race-based use of peremptory challenges,98 and considerations of race at sentencing.99 Due Process. The Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution prevents states from depriving “any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law.” This right includes protections against racial bias in criminal cases. For example, the Due Process Clause is an important source of rights for defendants challenging an unreliably suggestive cross-racial identification.100 Fourth Amendment. -

Effect of the Right to Speedy Trial on Nolle Prosequi William S

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of North Carolina School of Law NORTH CAROLINA LAW REVIEW Volume 46 | Number 2 Article 7 2-1-1968 Constitutional Law -- Effect of the Right to Speedy Trial on Nolle Prosequi William S. Geimer Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation William S. Geimer, Constitutional Law -- Effect of the Right to Speedy Trial on Nolle Prosequi, 46 N.C. L. Rev. 387 (1968). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr/vol46/iss2/7 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Law Review by an authorized editor of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 19681 RIGHT TO SPEEDY TRIAL allow the court to continue the appointment if it determined counsel was required.50 STEPHEN E. CULBRETHr Constitutional Law-Effect of the Right to Speedy Trial on Nolle Prosequi In Klopfer v. North Carolina,'theUnited States Supreme Court held that the sixth amendment guarantee of the right to speedy trial is a basic right protected by the Constitution and is therefore incorporated into the due process clause and made obligatory upon the states under the fourteenth amendment.2 Implicit in the de- cision is the proposition that the speedy trial guarantee is to be en- forced against the states according to the federal standard.3 In Klopfer, a violation of the sixth amendment was found in the use of the North Carolina procedural device of "nolle prosequi with leave." Its objectionable characteristic is the power given the state solicitor to suspend indefinitely action on a case, after an indictment has been filed, and notwithstanding defendant's timely demand for trial. -

Face to Face': Rediscovering the Right to Confront Prosecution Witnesses Richard D

University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository Articles Faculty Scholarship 2004 Face to Face': Rediscovering the Right to Confront Prosecution Witnesses Richard D. Friedman University of Michigan Law School, [email protected] Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles/728 Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles Part of the Common Law Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, and the Evidence Commons Recommended Citation Friedman, Richard D. "'Face to Face': Rediscovering the Right to Confront Prosecution Witnesses." Int'l J. Evidence & Proof 8, no. 1 (2004): 1-30. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 'Face to face': Rediscovering the right to confront prosecution witnesses By Richard D. Friedman* Ralph W.Aigler Professor of Law, University of Michigan Law School Abstract. The Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution protects the right of an accused 'to confront the witnesses against him'. The United States Supreme Court has treated this Confrontation Clause as a broad but rather easily rebuttable rule against using hearsay on behalf of a criminal prosecution; with respect to most hearsay, the exclusionary rule is overcome if the court is persuaded that the statement is sufficiently reliable, and the court can reach that conclusion if the statement fits within a 'firmly rooted' hearsay exception. -

The Implications of Incorporating the Eighth Amendment Prohibition on Excessive Bail

Hofstra Law Review Volume 43 | Issue 4 Article 4 1-1-2015 The mplicI ations of Incorporating the Eighth Amendment Prohibition on Excessive Bail Scott .W Howe Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Howe, Scott .W (2015) "The mpI lications of Incorporating the Eighth Amendment Prohibition on Excessive Bail," Hofstra Law Review: Vol. 43: Iss. 4, Article 4. Available at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr/vol43/iss4/4 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Howe: The Implications of Incorporating the Eighth Amendment Prohibitio THE IMPLICATIONS OF INCORPORATING THE EIGHTH AMENDMENT PROHIBITION ON EXCESSIVE BAIL Scott W.Howe* I. INTRODUCTION The Eighth Amendment prohibition on "excessive bail"' is perhaps the least developed of the criminal clauses in the Bill of Rights.2 The reasons have nothing to do with a scarcity of complaints about excessive bail in the trial courts. At any given time, about 500,000 criminally accused persons languish in jail in the United States,4 and not only defense lawyers in individual cases, but legal scholars who have studied the broader spectrum of cases regularly contend that many of these detentions are unnecessary.' Yet, claims of excessive bail virtually never receive an airing in the Supreme Court,6 unlike claims, for example, about unreasonable police invasions of privacy, 7 improper police interrogations,8 or cruel and unusual punishments.