Amicus Brief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The “Radical” Notion of the Presumption of Innocence

EXECUTIVE SESSION ON THE FUTURE OF JUSTICE POLICY THE “RADICAL” MAY 2020 Tracey Meares, NOTION OF THE Justice Collaboratory, Yale University Arthur Rizer, PRESUMPTION R Street Institute OF INNOCENCE The Square One Project aims to incubate new thinking on our response to crime, promote more effective strategies, and contribute to a new narrative of justice in America. Learn more about the Square One Project at squareonejustice.org The Executive Session was created with support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation as part of the Safety and Justice Challenge, which seeks to reduce over-incarceration by changing the way America thinks about and uses jails. 04 08 14 INTRODUCTION THE CURRENT STATE OF WHY DOES THE PRETRIAL DETENTION PRESUMPTION OF INNOCENCE MATTER? 18 24 29 THE IMPACT OF WHEN IS PRETRIAL WHERE DO WE GO FROM PRETRIAL DETENTION DETENTION HERE? ALTERNATIVES APPROPRIATE? TO AND SAFEGUARDS AROUND PRETRIAL DETENTION 33 35 37 CONCLUSION ENDNOTES REFERENCES 41 41 42 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AUTHOR NOTE MEMBERS OF THE EXECUTIVE SESSION ON THE FUTURE OF JUSTICE POLICY 04 THE ‘RADICAL’ NOTION OF THE PRESUMPTION OF INNOCENCE “It was the smell of [] death, it was the death of a person’s hope, it was the death of a person’s ability to live the American dream.” That is how Dr. Nneka Jones Tapia described the Cook County Jail where she served as the institution’s warden (from May 2015 to March 2018). This is where we must begin. EXECUTIVE SESSION ON THE FUTURE OF JUSTICE POLICY 05 THE ‘RADICAL’ NOTION OF THE PRESUMPTION OF INNOCENCE Any discussion of pretrial detention must Let’s not forget that Kalief Browder spent acknowledge that we subject citizens— three years of his life in Rikers, held on presumed innocent of the crimes with probable cause that he had stolen a backpack which they are charged—to something containing money, a credit card, and an iPod that resembles death. -

Demanding a Speedy Trial: Re-Evaluating the Assertion Factor in the Baker V

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 67 Issue 1 Article 12 2016 Demanding a Speedy Trial: Re-Evaluating the Assertion Factor in the Baker v. Wingo Test Seth Osnowitz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Seth Osnowitz, Demanding a Speedy Trial: Re-Evaluating the Assertion Factor in the Baker v. Wingo Test, 67 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 273 (2016) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol67/iss1/12 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 67·Issue 1·2016 Demanding a Speedy Trial: Re-Evaluating the Assertion Factor in the Barker v. Wingo Test Contents Introduction .................................................................................. 273 I. Background and Policy of Sixth Amendment Right to Speedy Trial .......................................................................... 275 A. History of Speedy Trial Jurisprudence ............................................ 276 B. Policy Considerations and the “Demand-Waiver Rule”..................... 279 II. The Barker Test and Defendants’ Assertion of the Right to a Speedy Trial .................................................................. 282 A. Rejection of the -

Speedy Trial

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 68 Article 7 Issue 4 December Winter 1977 Speedy Trial Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Speedy Trial, 68 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 543 (1977) This Criminal Law is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAW & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 68, No. 4 Copyright @ 1977 by Northwestern University School of Law Printed in U.S.A. SPEEDY TRIAL United States v. Lovasco, 97 S. Ct. 2044 (1977). The Supreme Court of the United States has v. Marion,7 the Supreme Court focused on the recognized that the right to a speedy trial "is language of the sixth amendment8 and con- one of the most basic rights preserved by our cluded that the sixth amendment speedy trial Constitution."' The right, as encompassed by provision does not apply until an individual the sixth amendment to the United States Con- becomes an accused, that is either through stitution,2 can be traced to the Magna Carta of arrest or indictment. The Court also stated 1215,3 which states, "we will sell to no man, we that Rule 48(b) of the Federal Rules of Criminal will not deny or defer to any man either justice Procedure9 is limited in application to post- or right. -

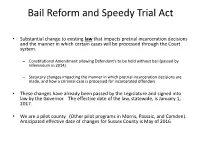

Bail Reform and Speedy Trial Act

Bail Reform and Speedy Trial Act • Substantial change to existing law that impacts pretrial incarceration decisions and the manner in which certain cases will be processed through the Court system. – Constitutional Amendment allowing Defendant’s to be held without bail (passed by referendum in 2014) – Statutory changes impacting the manner in which pretrial incarceration decisions are made, and how a criminal case is processed for incarcerated offenders • These changes have already been passed by the Legislature and signed into law by the Governor. The effective date of the law, statewide, is January 1, 2017. • We are a pilot county. (Other pilot programs in Morris, Passaic, and Camden). Anticipated effective date of changes for Sussex County is May of 2016. Current Processing of a Criminal Case ARREST/CHARGE SUMMONS WARRANT Central Judicial 1st Appearance/Bail AP not Processing Review (within 72 AP is present Hours) present Plea Hearing Case Resolved Early Case Not Resolved Grand Jury Disposition Presentation Conference Sentencing Arraignment Conference Status Conference Pre-Trial Conference Trial Aspects of Existing System That Will Change • Under the current system, the SCPO is not required, and does not, have an AP present at CJP Court. − CJP Court currently sits 1 day per week and is in session for about 4 hours • Under the current system, for defendants remanded to the jail on a warrant, no weekend appearance is necessary. − This is so because the first appearance/bail review does not need to take place for 72 hours. − Therefore, for a defendant arrested on a Friday, we can legally wait until Monday for the first appearance/bail review Aspects of Existing System That Will Change (Continued) • Under the current system, there are no lengthy testimonial hearings prior to the EDC conference. -

Effect of the Right to Speedy Trial on Nolle Prosequi William S

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of North Carolina School of Law NORTH CAROLINA LAW REVIEW Volume 46 | Number 2 Article 7 2-1-1968 Constitutional Law -- Effect of the Right to Speedy Trial on Nolle Prosequi William S. Geimer Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation William S. Geimer, Constitutional Law -- Effect of the Right to Speedy Trial on Nolle Prosequi, 46 N.C. L. Rev. 387 (1968). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr/vol46/iss2/7 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Law Review by an authorized editor of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 19681 RIGHT TO SPEEDY TRIAL allow the court to continue the appointment if it determined counsel was required.50 STEPHEN E. CULBRETHr Constitutional Law-Effect of the Right to Speedy Trial on Nolle Prosequi In Klopfer v. North Carolina,'theUnited States Supreme Court held that the sixth amendment guarantee of the right to speedy trial is a basic right protected by the Constitution and is therefore incorporated into the due process clause and made obligatory upon the states under the fourteenth amendment.2 Implicit in the de- cision is the proposition that the speedy trial guarantee is to be en- forced against the states according to the federal standard.3 In Klopfer, a violation of the sixth amendment was found in the use of the North Carolina procedural device of "nolle prosequi with leave." Its objectionable characteristic is the power given the state solicitor to suspend indefinitely action on a case, after an indictment has been filed, and notwithstanding defendant's timely demand for trial. -

Florida's New Speedy Trial Rule: the "Window of Recapture"

Florida State University Law Review Volume 13 Issue 1 Article 2 Spring 1985 Florida's New Speedy Trial Rule: The "Window of Recapture" John F. Yetter Florida State University College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the Criminal Procedure Commons Recommended Citation John F. Yetter, Florida's New Speedy Trial Rule: The "Window of Recapture", 13 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 9 (1985) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol13/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA'S NEW SPEEDY TRIAL RULE: THE "WINDOW OF RECAPTURE" JOHN F. YETTER* The Florida Supreme Court amended the criminal speedy trial rule, Rule 3.191, Florida Rules of Criminal Procedure, effective January 1, 1985.1 Under the previous rule, an accused was abso- lutely discharged from prosecution if the time provisions were vio- * Professor of Criminal Law and Associate Dean, Florida State University. Chairman, Criminal Procedure Rules Committee of the Florida Bar. Lehigh University, B.A., B.S., 1963; Duquesne University, J.D., 1967; Yale University, LLM., 1968. 1. Florida Bar Re: Amendment to Rules-Criminal Procedure, 462 So. 2d 386 (Fla. 1984). Neither the amendment, nor the commentary to it, contains any provision relating to the transitional period. The state may contend that the amendment permits recapture of defendants in any case where the underlying speedy trial time had not expired as of January 1, 1985. -

Speedy Trials: Recent Developments Concerning a Vital Right Stephen F

Fordham Urban Law Journal Volume 4 4 Article 6 Number 2 1976 Speedy Trials: Recent Developments Concerning a Vital Right Stephen F. Chepiga Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Stephen F. Chepiga, Speedy Trials: Recent Developments Concerning a Vital Right, 4 Fordham Urb. L.J. 351 (1976). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol4/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Urban Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTES SPEEDY TRIALS: RECENT DEVELOPMENTS CONCERNING A VITAL RIGHT I. Introduction Historically, Anglo-American law has jealously guarded the right of an accused to have a speedy trial in a criminal prosecution., Englishmen formally claimed the right in the Magna Charta of 1215.2 In the United States, it is extended to defendants in. federal cases by the sixth amendment to the Constitution.' Through incor- poration into the fourteenth amendment, the protection is likewise available to defendants in state prosecutions.' Notwithstanding constitutional provisions and Supreme Court decisions, the concept of a speedy trial in the United States has always been ambiguous. Until recent times it has been considered a matter that could only be defined in the context of the special circumstances of individual cases.5 The right was said to be "consis- tent with delays"; 6 thus there has been less than an absolute guar- antee that a defendant would be tried within a short time of his arrest or indictment. -

Local Ref.Pdf

Table of Contents (Nominal) CONTENTS Page No. Chapter 1. Introduction 1-16 Chapter 2. Data Analysis 17-89 Chapter 3: Major findings 90-117 Chapter 4: How long the Wheels of Justice shall hold 118-144 on for appearance of the accused? Chapter 5: Whose case is it in any way? Police, 145-166 Prosecution or the Victim Chapter 6 Can there be a time frame for completing 167-175 Investigation? Chapter 7 Recommendations 176-182 i Table of Contents (Detailed) Chapter Page No. CONTENTS No. List of Abbreviations vii List of Cases viii - x List of Tables xi Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION 1-16 A. What amounts to delay? 7-13 B. Objectives of the Study 14 C. Limitations of the Study 14 D. Methodology 14-16 Chapter 2 DATA ANALYSIS 17-89 A. Stage I: Analysis of Form 1 17-29 B. State II: Analysis of Form 2, 3 and 4 30-40 C. Stage III: Sample Study of life cycle of 41-49 pending and disposed of cases D. Stage IV: Questionnaires 50-89 Chapter 3 MAJOR FINDINGS 90-117 A. Non-appearance of the accused at 90-95 different stages of Trial B. Fall out of absconding on criminal 95-98 ii adjudication C. Procedural and penal safeguards to 98-102 check and deal with non-appearance of the accused D. How far Sec.299 Cr.P.C been 102-107 effective? E. Avoidable delays at the stage of 107-111 commitment of cases to the court of sessions F. Delay at the stage of Prosecution 111-116 Evidence G. -

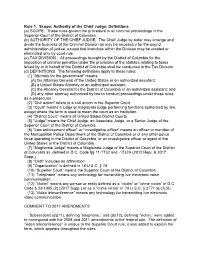

Rule 1. Scope; Authority of the Chief Judge; Definitions (A) SCOPE

Rule 1. Scope; Authority of the Chief Judge; Definitions (a) SCOPE. These rules govern the procedure in all criminal proceedings in the Superior Court of the District of Columbia. (b) AUTHORITY OF THE CHIEF JUDGE. The Chief Judge by order may arrange and divide the business of the Criminal Division as may be necessary for the sound administration of justice, except that branches within the Division may be created or eliminated only by court rule. (c) TAX DIVISION. All proceedings brought by the District of Columbia for the imposition of criminal penalties under the provisions of the statutes relating to taxes levied by or in behalf of the District of Columbia shall be conducted in the Tax Division. (d) DEFINITIONS. The following definitions apply to these rules: (1) “Attorney for the government” means: (A) the Attorney General of the United States or an authorized assistant; (B) a United States Attorney or an authorized assistant; (C) the Attorney General for the District of Columbia or an authorized assistant; and (D) any other attorney authorized by law to conduct proceedings under these rules as a prosecutor. (2) “Civil action” refers to a civil action in the Superior Court. (3) “Court” means a judge or magistrate judge performing functions authorized by law, except where the term is used to mean the court as an institution. (4) “District Court” means all United States District Courts. (5) “Judge” means the Chief Judge, an Associate Judge, or a Senior Judge of the Superior Court of the District of Columbia. (6) “Law enforcement officer” or “investigative officer” means an officer or member of the Metropolitan Police Department of the District of Columbia or of any other police force operating in the District of Columbia, or an investigative officer or agent of the United States or the District of Columbia. -

Speedy Trial and Related Issues

Chapter 7 Speedy Trial and Related Issues 7.1 Statutory Protections against Delayed Prosecution 7-2 A. Statute of Limitations for Misdemeanors B. Compliance with Statute of Limitations C. Waiver of Statute of Limitations D. Statutory Limitations on Jurisdiction of Juvenile Court E. Rights of Prisoners F. Pretrial Release G. Other Statutory Deadlines 7.2 Pre-Accusation Delay 7-13 A. Constitutional Basis of Right B. Proving Prejudice C. Reason for Delay D. Case Summaries on Pre-Accusation Delay E. Investigating Pre-Accusation Delay F. Motions to Dismiss 7.3 Post-Accusation Delay 7-17 A. Constitutional Basis of Right B. Test for Speedy Trial Violation C. When Right Attaches D. Case Summaries on Post-Accusation Delay E. Remedy for Speedy Trial Violation F. Motions for Speedy Trial 7.4 Prosecutor’s Calendaring Authority 7-29 A. Generally B. Simeon v. Hardin C. Calendaring Statute D. Other Limits E. District Court Proceedings ___________________________________________________________ This chapter covers four related issues concerning trial delay: • statutory protections against delayed prosecution of a criminal defendant; • constitutional protections against prolonged delay between the commission of the offense and the defendant’s arrest or indictment on the charge; 7-1 Ch. 7: Speedy Trial and Related Issues (Mar. 2019) 7-2 • constitutional protections against prolonged delay after arrest or indictment; and • limits on prosecutors’ use of their calendaring authority. The Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and the Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution, as well as analogous provisions in North Carolina’s Constitution (article I, sections 18 and 19), are the primary sources of law guaranteeing a defendant charged with a felony the right to a timely prosecution and a speedy trial. -

Speedy Trial Plan

SPEEDY TRIAL PLAN of the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA Local Criminal Rule 45.1 PLAN FOR THE DISPOSITION OF CRIMINAL CASES ADOPTED PURSUANT TO THE SPEEDY TRIAL ACT OF 1974 Pursuant to the provisions of 18 U.S.C. § 3165(c), the Plan for the Disposition of Criminal cases was approved by the Court on May 5, 1980, by the Judicial Counsel on May 13, 1980, and became effective July 1, 1980. This copy of the plan has been modified to incorporate the Court's practices as of October 30, 2002. Angela D. Caesar, Clerk UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA SPEEDY TRIAL PLAN TABLE OF SECTIONS A. Applicability and General Policy 1. Applicability (a) Other Rules (b) Offenses (c) Persons 2. Priorities in Scheduling Criminal Cases B. Time Limits and Related Provisions 3. Proceedings Before the Magistrate Judges (a) Time Limits Applicable to Preliminary Examinations (b) Bail Reports and Hearings 4. Time Within Which an Indictment or Information Must be Filed (a) Time Limits (b) Superseding Charges (c) Measurement of Time Periods (d) Related Procedures (e) Pre-Indictment Rulings on Excludable Time and Continuances 5. Time Within Which Arraignments Shall be Held (a) Time Limits (b) Measurement of Time Periods (c) Timing the Return of Indictments (d) Notification of Counsel and the Defendant (e) Transfer of Cases for Arraignment (f) Related Procedures 6. Time Within Which Pretrial Motions Must be Filed 1 7. Status Conference (a) Initial Conference (b) Further Hearings 8. Time Within Which Trial Must Commence (a) Time Limits (1) Time Limit Applicable to District Court (2) Time Limit Applicable to Trials Before Magistrates Judges (b) Retrial and Trial After Reinstatement of an Indictment or Information (c) Withdrawal of Plea (d) Superseding Charges (e) Measurement of Time Periods (f) Meeting the Scheduled Trial Date (1) In General (2) Transfer of Cases for Trial (g) Pretrial Rulings on Excludable Time and Continuances 9. -

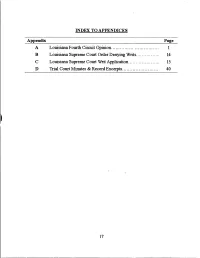

Appendix Page a Louisiana Fourth Circuit Opinion

INDEX TO APPENDICES Appendix Page A Louisiana Fourth Circuit Opinion................... 1 B Louisiana Supreme Court Order Denying Writs 14 C Louisiana Supreme Court Writ Application...... 15 D Trial Court Minutes & Record Excerpts........... 40 17 Office Of The Clerk Court of Appeal, Fourth Circuit Mailing Address: State of Louisiana 410 Royal Street Justin I. Woods New Orleans, Louisiana Clerk of Court 400 Royal Street 70130-2199 Third Floor (504) 412-6001 JoAnn Veal FAX (504) 412-6019 Chief Deputy Clerk of Court NOTICE OF -IUDGMENT AND CERTIFICATE OF MAILING I parties not represented by counsel, as listed below. jiw/rmi JUSTIN I. WOODS CLERK OF COURT 9018-KA-0777 C/W: 2018-K-1024 Michael Danon Nathaniel Lambert #90883 Donna Andrieu Sherry Watters MPEY/SPRUCE - 3 LOUISIANA APPELLATE PROJECT Leon Cannizzaro Louisiana State Prison District Attorney P. O. Box 58769 - Angola, LA 70712- New Orleans. LA 70158- ORLEANS PARISH 619 S. White Street New Orleans. LA 70119- ScottG. Vincent Assistant District Attorney 619 South White Street New Orleans, LA 70119- / STATE OF LOUISIANA NO. 2018-KA-0777 VERSUS COURT OF APPEAL NATHANIEL LAMBERT FOURTH CIRCUIT STATE OF LOUISIANA * * * * * * * CONSOLIDATED WITH: CONSOLIDATED WITH: STATE OF LOUISIANA NO. 2018-K-1024 VERSUS NATHANIEL LAMBERT APPEAL FROM CRIMINAL DISTRICT COURT ORLEANS PARISH NO. 387-752, SECTION “D” Honorable Paul A Bonin, Judge * * * * * * Judge Tiffany G. Chase * # * (Court composed of Judge Daniel L. Dysart, Judge Joy Cossich Lobrano, Judge Tiffany G. Chase) LOBRANO, J. CONCURS IN THE RESULT. Leon Cannizzaro, District Attorney Scott G. Vincent, Assistant District Attorney DISTRICT ATTORNEY’S OFFICE, ORLEANS PARISH 619 S.