Jutland: Acrimony to Resolution Holger Herwig

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

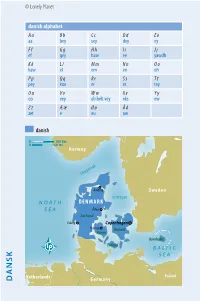

Danish Alphabet DENMARK Danish © Lonely Planet

© Lonely Planet danish alphabet A a B b C c D d E e aa bey sey dey ey F f G g H h I i J j ef gey haw ee yawdh K k L l M m N n O o kaw el em en oh P p Q q R r S s T t pey koo er es tey U u V v W w X x Y y oo vey do·belt vey eks ew Z z Æ æ Ø ø Å å zet e eu aw danish 0 100 km 0 60 mi Norway Skagerrak Aalborg Sweden Kattegat NORTH DENMARK SEA Århus Jutland Esberg Copenhagen Odense Zealand Funen Bornholm Lolland BALTIC SEA Poland Netherlands Germany DANSK DANSK DANISH dansk introduction What do the fairy tales of Hans Christian Andersen and the existentialist philosophy of Søren Kierkegaard have in common (apart from pondering the complexities of life and human character)? Danish (dansk dansk), of course – the language of the oldest European monarchy. Danish contributed to the English of today as a result of the Vi- king conquests of the British Isles in the form of numerous personal and place names, as well as many basic words. As a member of the Scandinavian or North Germanic language family, Danish is closely related to Swedish and Norwegian. It’s particularly close to one of the two official written forms of Norwegian, Bokmål – Danish was the ruling language in Norway between the 15th and 19th centuries, and was the base of this modern Norwegian literary language. In pronunciation, however, Danish differs considerably from both of its neighbours thanks to its softened consonants and often ‘swallowed’ sounds. -

CEMENT for BUILDING with AMBITION Aalborg Portland A/S Portland Aalborg Cover Photo: the Great Belt Bridge, Denmark

CEMENT FOR BUILDING WITH AMBITION Aalborg Portland A/S Cover photo: The Great Belt Bridge, Denmark. AALBORG Aalborg Portland Holding is owned by the Cementir Group, an inter- national supplier of cement and concrete. The Cementir Group’s PORTLAND head office is placed in Rome and the Group is listed on the Italian ONE OF THE LARGEST Stock Exchange in Milan. CEMENT PRODUCERS IN Cementir's global organization is THE NORDIC REGION divided into geographical regions, and Aalborg Portland A/S is included in the Nordic & Baltic region covering Aalborg Portland A/S has been a central pillar of the Northern Europe. business community in Denmark – and particularly North Jutland – for more than 125 years, with www.cementirholding.it major importance for employment, exports and development of industrial knowhow. Aalborg Portland is one of the largest producers of grey cement in the Nordic region and the world’s leading manufacturer of white cement. The company is at the forefront of energy-efficient production of high-quality cement at the plant in Aalborg. In addition to the factory in Aalborg, Aalborg Portland includes five sales subsidiaries in Iceland, Poland, France, Belgium and Russia. Aalborg Portland is part of Aalborg Portland Holding, which is the parent company of a number of cement and concrete companies in i.a. the Nordic countries, Belgium, USA, Turkey, Egypt, Malaysia and China. Additionally, the Group has acti vities within extraction and sales of aggregates (granite and gravel) and recycling of waste products. Read more on www.aalborgportlandholding.com, www.aalborgportland.dk and www.aalborgwhite.com. Data in this brochure is based on figures from 2017, unless otherwise stated. -

Les Îles De La Manche ~ the Channel Islands

ROLL OF HONOUR 1 The Battle of Jutland Bank ~ 31st May 1916 Les Îles de la Manche ~ The Channel Islands In honour of our Thirty Six Channel Islanders of the Royal Navy “Blue Jackets” who gave their lives during the largest naval battle of the Great War 31st May 1916 to 1st June 1916. Supplement: Mark Bougourd ~ The Channel Islands Great War Study Group. Roll of Honour Battle of Jutland Les Îles de la Manche ~ The Channel Islands Charles Henry Bean 176620 (Portsmouth Division) Engine Room Artificer 3rd Class H.M.S. QUEEN MARY. Born at Vale, Guernsey 12 th March 1874 - K.I.A. 31 st May 1916 (Age 42) Wilfred Severin Bullimore 229615 (Portsmouth Division) Leading Seaman H.M.S. INVINCIBLE. Born at St. Sampson, Guernsey 30 th November 1887 – K.I.A. 31 st May 1916 (Age 28) Wilfred Douglas Cochrane 194404 (Portsmouth Division) Able Seaman H.M.S. BLACK PRINCE. Born at St. Peter Port, Guernsey 30 th September 1881 – K.I.A. 31 st May 1916 (Age 34) Henry Louis Cotillard K.20827 (Portsmouth Division) Stoker 1 st Class H.M.S. BLACK PRINCE. Born at Jersey, 2 nd April 1893 – K.I.A. 31 st May 1916 (Age 23) John Alexander de Caen 178605 (Portsmouth Division) Petty Officer 1 st Class H.M.S. INDEFATIGABLE. Born at St. Helier, Jersey 7th February 1879 – K.I.A. 31 st May 1916 (Age 37) The Channel Islands Great War Study Group. - 2 - Centenary ~ The Battle of Jutland Bank www.greatwarci.net © 2016 ~ Mark Bougourd Roll of Honour Battle of Jutland Les Îles de la Manche ~ The Channel Islands Stanley Nelson de Quetteville Royal Canadian Navy Lieutenant (Engineer) H.M.S. -

Jabberwock No 85

BERWO JAB CK The Magazine of the Society of Friends of the Fleet Air Arm Museum IN THISIN THIS EDITION: EDITION: • Memoirs of Captain Keith Leppard and Sqn Ldr Maurice Biggs • Peter Twiss • Christmas Lunch notice • Hawker Sea Fury detail • The first angled deck • HMS Engadine at theBattle of Jutland • Society Visit to the Meteorological Office • Book Review - “Air War in the Mediterranean” PLUS: All the usual features; news from the Museum, snippets from Council meetings, monthly talks programme, latest membership numbers... No. 85 November 2016 No. 85 November 2016 Published by The Society of Friends of the Fleet Air Arm Museum Published by The Society of Friends of the Fleet Air Arm Museum Jabberwock No 85. November 2016 Patron: Rear Admiral A R Rawbone CB, AFC, RN President: Gordon Johnson FLEET AIR ARM MUSEUM RNAS Yeovilton Somerset BA22 8HT Telephone: 01935 840565 SOFFAAM email: [email protected] SOFFAAM website: fleetairarmfriends.org.uk Registered Charity No. 280725 Sunset - HMS Illustrious 1 Jabberwock No 85. November 2016 The Society of Friends of the Fleet Air Arm Museum Admission Vice Presidents Members are admitted to the Museum Rear Admiral A R Rawbone CB, AFC, RN free of charge, on production of a valid F C Ott DSC BSc (Econ) membership card. Members may be Lt Cdr Philip (Jan) Stuart RN accompanied by up to three guests (one David Kinloch guest only for junior members) on any Derek Moxley one visit, each at a reduced entrance Gerry Sheppard fee, currently 50% of the standard price. Members are also allowed a 10% Bill Reeks discount on goods purchased from the shop. -

Channel Islanders Who Fell on the Somme

JOURNAL August 62 2016 ‘General Salute, Present Arms’ At Thiepval 1st July, 2016 Please note that Copyright responsibility for the articles contained in this Journal rests with the Authors as shown. Please contact them directly if you wish to use their material. 1 IN REMEMBRANCE OF THOSE WHO FELL 1st August, 1916 to 31st October, 1916 August, 1916 01. Adams, Frank Herries 17. Flux, Charles Thomas 01. Jefferys, Ernest William 17. Russell, Thomas 01. Neyrand, Charles Jacques AM 17. Stone, Frederick William 01. Powney, Frank 18. Bailey, Stanley George 03. Courtman, Walter Herbert 18. Berty, Paul Charles 03. Hamon, Alfred 18. Marriette, William Henry 03. Loader, Percy Augustus 18. Meagher, William Edward 03. Wimms, John Basil Thomas 18. Warne, Albert Edward 05. Dallier, Léon Eugène 19. Churchill, Samuel George 05. Du Heaume, Herbert Thomas 19. Hill, Charles Percy 05. Villalard, John Francis 19. Le Cocq, Yves Morris E 06. Muspratt, Frederic 21. Le Venois, Léon 08. Rouault, Laurent Pierre 23. Collings, Eric d’Auvergne 09. Sinnatt, William Hardie 24. Cleal, Edward A 10. Falla, Edward 24. Gould, Patrick Wallace 11. Mitchell, Clifford George William 24. Herauville, Louis Eugène Auguste 12. Davis, Howard Leopold 24. Le Rossignol, Wilfred 12. Game, Ambrose Edward 26. Capewell, Louis, Joseph 12. Hibbs, Jeffery 26. Harel, Pierre 12. Jeanvrin, Aimé Ferdinand 26. Le Marquand, Edward Charles 13. Balston, Louis Alfred 27. Guerin, John Francis Marie 15. de Garis, Harold 28. Greig, Ronald Henry 16. Bessin, Charles 28. Guerin, Léon Maximillien 16. De la Haye, Clarence John 29. Le Masurier, John George Walter 17. Fleury, Ernest September, 1916 01. -

Midshipman Trevor George Lawless HAYLES, HMS Defence

GREAT WAR STAINED GLASS WINDOW MEMORIALS IN KENT No. 10: St Mary’s, Greenhithe Midshipman Trevor George Lawless Hayles HMS Defence KIA 31 May 1916, Battle of Jutland Window: St Mary’s, Greenhithe Kent links: Birthplace, Family home Medals: British and Victory medals War Grave: Plymouth Naval Memorial HMS Defence (left) and HMS Warrior at 6.20pm 31May 1916 Source: www.europeana1914-1918en/en/europeana/record/2022362 Trevor George Lawless Hayles was born on 11 March 1900 in Rainham, Kent.1 He was the only child of Trevor and Millie (née Lawless) Hayles, who had married in Croydon in June 1899. Millie was the daughter of an army surgeon. Trevor Hayles Snr, son of a broker, was at this time an Assistant Paymaster in the Royal Navy based at Southsea.2 He was subsequently to spend most of the Great War commanding the General Mess and Cookery School at Chatham, except for a few months from August 1918 when he was posted to the staff of the C-in-C Mediterranean.3 He retired from the navy in 1928, with the rank of Rear-Admiral Paymaster, and served in the Home Guard in 1940.4 He and his wife eventually retired to Malta, where they died within months of each other in 1959.5 1 Service Record, Trevor George Lawless Hayles, TNA PRO ADM/196/123. 2 Surrey Church of England Marriage Registers, Ancestry.Co. 3 Service Record, Trevor Hayles, TNA PRO ADM/196/82. 4 Service Record, Trevor Hayles, TNA PRO ADM/196/172. 5 Probate Records, April and June 1959, Ancestry.Co. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

Primary Source and Background Documents D

Note: Original spelling is retained for this document and all that follow. Appendix 1: Primary source and background documents Document No. 1: Germany's Declaration of War with Russia, August 1, 1914 Presented by the German Ambassador to St. Petersburg The Imperial German Government have used every effort since the beginning of the crisis to bring about a peaceful settlement. In compliance with a wish expressed to him by His Majesty the Emperor of Russia, the German Emperor had undertaken, in concert with Great Britain, the part of mediator between the Cabinets of Vienna and St. Petersburg; but Russia, without waiting for any result, proceeded to a general mobilisation of her forces both on land and sea. In consequence of this threatening step, which was not justified by any military proceedings on the part of Germany, the German Empire was faced by a grave and imminent danger. If the German Government had failed to guard against this peril, they would have compromised the safety and the very existence of Germany. The German Government were, therefore, obliged to make representations to the Government of His Majesty the Emperor of All the Russias and to insist upon a cessation of the aforesaid military acts. Russia having refused to comply with this demand, and having shown by this refusal that her action was directed against Germany, I have the honour, on the instructions of my Government, to inform your Excellency as follows: His Majesty the Emperor, my august Sovereign, in the name of the German Empire, accepts the challenge, and considers himself at war with Russia. -

Memoirs of Hydrography

MEMOIRS 07 HYDROGRAPHY INCLUDING Brief Biographies of the Principal Officers who have Served in H.M. NAVAL SURVEYING SERVICE BETWEEN THE YEARS 1750 and 1885 COMPILED BY COMMANDER L. S. DAWSON, R.N. I 1s t tw o PARTS. P a r t II.—1830 t o 1885. EASTBOURNE: HENRY W. KEAY, THE “ IMPERIAL LIBRARY.” iI i / PREF A CE. N the compilation of Part II. of the Memoirs of Hydrography, the endeavour has been to give the services of the many excellent surveying I officers of the late Indian Navy, equal prominence with those of the Royal Navy. Except in the geographical abridgment, under the heading of “ Progress of Martne Surveys” attached to the Memoirs of the various Hydrographers, the personal services of officers still on the Active List, and employed in the surveying service of the Royal Navy, have not been alluded to ; thereby the lines of official etiquette will not have been over-stepped. L. S. D. January , 1885. CONTENTS OF PART II ♦ CHAPTER I. Beaufort, Progress 1829 to 1854, Fitzroy, Belcher, Graves, Raper, Blackwood, Barrai, Arlett, Frazer, Owen Stanley, J. L. Stokes, Sulivan, Berard, Collinson, Lloyd, Otter, Kellett, La Place, Schubert, Haines,' Nolloth, Brock, Spratt, C. G. Robinson, Sheringham, Williams, Becher, Bate, Church, Powell, E. J. Bedford, Elwon, Ethersey, Carless, G. A. Bedford, James Wood, Wolfe, Balleny, Wilkes, W. Allen, Maury, Miles, Mooney, R. B. Beechey, P. Shortland, Yule, Lord, Burdwood, Dayman, Drury, Barrow, Christopher, John Wood, Harding, Kortright, Johnson, Du Petit Thouars, Lawrance, Klint, W. Smyth, Dunsterville, Cox, F. W. L. Thomas, Biddlecombe, Gordon, Bird Allen, Curtis, Edye, F. -

Download the Full PDF Here

THE PHILADELPHIA PAPERS A Publication of the Foreign Policy Research Institute GREAT WAR AT SEA: REMEMBERING THE BATTLE OF JUTLAND by John H. Maurer May 2016 13 FOREIGN POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE THE PHILADELPHIA PAPERS, NO. 13 GREAT WAR AT SEA: REMEMBERING THE BATTLE OF JUTLAND BY JOHN H. MAURER MAY 2016 www.fpri.org 1 THE PHILADELPHIA PAPERS ABOUT THE FOREIGN POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE Founded in 1955 by Ambassador Robert Strausz-Hupé, FPRI is a non-partisan, non-profit organization devoted to bringing the insights of scholarship to bear on the development of policies that advance U.S. national interests. In the tradition of Strausz-Hupé, FPRI embraces history and geography to illuminate foreign policy challenges facing the United States. In 1990, FPRI established the Wachman Center, and subsequently the Butcher History Institute, to foster civic and international literacy in the community and in the classroom. ABOUT THE AUTHOR John H. Maurer is a Senior Fellow of the Foreign Policy Research Institute. He also serves as the Alfred Thayer Mahan Professor of Sea Power and Grand Strategy at the Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island. The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone, and do not represent the settled policy of the Naval War College, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. Foreign Policy Research Institute 1528 Walnut Street, Suite 610 • Philadelphia, PA 19102-3684 Tel. 215-732-3774 • Fax 215-732-4401 FOREIGN POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE 2 Executive Summary This essay draws on Maurer’s talk at our history institute for teachers on America’s Entry into World War I, hosted and cosponsored by the First Division Museum at Cantigny in Wheaton, IL, April 9-10, 2016. -

Military History Anniversaries 16 Thru 30 June

Military History Anniversaries 16 thru 30 June Events in History over the next 15 day period that had U.S. military involvement or impacted in some way on U.S military operations or American interests Jun 16 1832 – Native Americans: Battle of Burr Oak Grove » The Battle is either of two minor battles, or skirmishes, fought during the Black Hawk War in U.S. state of Illinois, in present-day Stephenson County at and near Kellogg's Grove. In the first skirmish, also known as the Battle of Burr Oak Grove, on 16 JUN, Illinois militia forces fought against a band of at least 80 Native Americans. During the battle three militia men under the command of Adam W. Snyder were killed in action. The second battle occurred nine days later when a larger Sauk and Fox band, under the command of Black Hawk, attacked Major John Dement's detachment and killed five militia men. The second battle is known for playing a role in Abraham Lincoln's short career in the Illinois militia. He was part of a relief company sent to the grove on 26 JUN and he helped bury the dead. He made a statement about the incident years later which was recollected in Carl Sandburg's writing, among others. Sources conflict about who actually won the battle; it has been called a "rout" for both sides. The battle was the last on Illinois soil during the Black Hawk War. Jun 16 1861 – Civil War: Battle of Secessionville » A Union attempt to capture Charleston, South Carolina, is thwarted when the Confederates turn back an attack at Secessionville, just south of the city on James Island. -

Maltese Casualties in the Battle of Jutland - May 31- June 1, 1916

., ~ I\ ' ' "" ,, ~ ·r " ' •i · f.;IHJ'¥T\f 1l,.l~-!l1 MAY 26, 2019 I 55 5~ I MAY 26, 2019 THE SUNDAY TIMES OF MALTA THE SUNDAY TIMES OF MALTA LIFE&WELLBEING HISTORY Maltese casualties in the Battle of Jutland - May 31- June 1, 1916 .. PATRICK FARRUGIA .... .. HMS Defence .. HMS lndefatigab!.e sinking HMS Black Prince ... In the afternoon and evening·of .. May 31, 1916, the Battle of Jutland (or Skagerrakschlact as it is krnwn •. to the Germans), was fought between the British Grand Fleet, under the command of Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, and the German High Seas Fleet commanded by Admiral Reinhold Scheer. It was to be the largest nava~ bat tle and the only full.-scale clash between battleships of the war. The British Grand Fleet was com posed of 151 warships, among which were 28 bat:leships and nine battle cruisers, wiile the German High Seas Fleet consisted of 99 war ships, including 16 battleships and 54 battle cruisers. Contact between these mighty fleets was made shortly after 2pm, when HMS Galatea reported that she had sighted the enemy. The first British disaster occured at 4pm, when, while engaging SMS Von der Tann, HMS Indefatigable was hit by a salvo onherupperdeck. The amidships. A huge pillar of smoke baden when they soon came under Giovanni Consiglio, Nicolo FOndac Giuseppe Cuomo and Achille the wounded men was Spiro Borg, and 5,769 men killed, among them missiles apparently penetrated her ascended to the sky, and she sank attack of the approaching battle aro, Emmanuele Ligrestischiros, Polizzi, resi1ing in Valletta, also lost son of Lorenzo and Lorenza Borg 72 men with a Malta connection; 25 'X' magazine, for she was sudcenly bow first.