Agents with Faces - What Can We Learn from LEGO Minfigures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

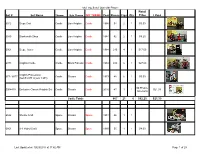

Lego Sets I Own with Picture Retail Set # Set Name Theme Sub Theme MY THEME Year Pieces Figs Qty Price I Paid

My Lego Sets I Own with Picture Retail Set # Set Name Theme Sub Theme MY THEME Year Pieces Figs Qty Price I Paid 6012 Siege Cart Castle Lion Knights Castle 1986 54 2 1 $3.50 6040 Blacksmith Shop Castle Lion Knights Castle 1984 92 2 1 $9.25 6061 Siege Tower Castle Lion Knights Castle 1984 216 4 1 $17.50 6073 Knights Castle Castle Black Falcons Castle 1984 410 6 1 $27.00 Knights Procession 677 / 6077 Castle Classic Castle 1979 48 6 1 $5.00 (Set # 6077 is year 1981) $0 Promo- 5004419 Exclusive Classic Knights Set Castle Classic Castle 2016 47 1 1 $21.39 Giveaway Castle Totals 867 21 6 $62.25 $21.39 6842 Shuttle Craft Space Classic Space 1981 46 1 1 6861 X-1 Patrol Craft Space Classic Space 1980 55 1 1 $4.00 Last Updated on 10/29/2017 at 11:42 AM Page 1 of 29 My Lego Sets I Own with Picture Retail Set # Set Name Theme Sub Theme MY THEME Year Pieces Figs Qty Price I Paid 6880 Surface Explorer Space Classic Space 1982 82 1 1 $7.50 6927 All Terrain Vehicle Space Classic Space 1981 170 2 1 $14.50 452 Mobile Tracking Station Space Classic Space 1979 76 1 1 462 Rocket Launcher Space Classic Space 1978 76 2 1 483 Alpha 1 Rocket Base Space Classic Space 1978 187 3 1 Space Totals 692 11 7 $26.00 $0.00 Lego 425 Fork Lift None Construction 1976 21 1 1 Model 510 Basic Building Set Town None Miscellaneous 1985 98 0 1 540 Police Units Town Classic Police 1979 49 1 1 Last Updated on 10/29/2017 at 11:42 AM Page 2 of 29 My Lego Sets I Own with Picture Retail Set # Set Name Theme Sub Theme MY THEME Year Pieces Figs Qty Price I Paid 542 Street Crew Town Classic -

Annual Report 2003 LEGO Company CONTENTS

Annual Report 2003 LEGO Company CONTENTS Report 2003 . page 3 Play materials – page 3 LEGOLAND® parks – page 4 LEGO Brand Stores – page 6 The future – page 6 Organisation and leadership – page 7 Expectations for 2004 – page 9 The LEGO® brand. page 11 The LEGO universe and consumers – page 12 People and Culture . page 17 The Company’s responsibility . page 21 Accounts 2003. page 24 Risk factors – page 24 Income statement – page 25 Notes – page 29 LEGO A/S Board of Directors: Leadership Team: * Mads Øvlisen, Chairman Dominic Galvin (Brand Retail) Kjeld Kirk Kristiansen, Vice Chairman Tommy G. Jespersen (Supply Chain) Gunnar Brock Jørgen Vig Knudstorp (Corporate Affairs) Mogens Johansen Søren Torp Laursen (Americas) Lars Kann-Rasmussen Mads Nipper (Innovation and Marketing) Anders Moberg Jesper Ovesen (Corporate Finance) Henrik Poulsen (European Markets & LEGO Trading) President and CEO: Arthur Yoshinami (Asia/Pacific) Kjeld Kirk Kristiansen Mads Ryder (LEGOLAND parks) * Leadership Team after changes in early 2004 LEGO, LEGO logo, the Brick Configuration, Minifigure, DUPLO, CLIKITS logo, BIONICLE, MINDSTORMS, LEGOLAND and PLAY ON are trademarks of the LEGO Group. © 2004 The LEGO Group 2 | ANNUAL REPORT 2003 Annual Report 2003 2003 was a very disappointing year for LEGO tional toy market stagnated in 2003, whereas Company. the trendier part of the market saw progress. Net sales fell by 26 percent from DKK 11.4 bil- The intensified competition in the traditional lion in 2002 to DKK 8.4 billion. Play material toy market resulted in a loss of market share sales declined by 29 percent to DKK 7.2 bil- in most markets – partly to competitors who lion. -

Happy Holidays!

GREAT GIFT HAPPY HOLIDAYS! Light brick IDEAS! Press down on the chimney- Holiday Sets smoke button AGES 6+ 1 to set the fire aglow! Gingerbread House LEGO® WHAT’S NEW? Harry Potter Check out the new holiday sets: Gingerbread House, 10267 AGES 12+ 1,477 PIECES AGES 7+ 5 R E E LE® Star Wars™ Enjoy a festive build-and-play experience with the LEGO® Creator LEGO® sets, LEGO Disney Frozen II sets and more! Expert 10267 Gingerbread House. A treasure chest of magical details, this amazing model features frosted roofs with colorful candy buttons Creator Expert AGES 12+ 8 and a delicious facade with candy-cane columns, glittery windows BENEFITS & SERVICE and a tall chimney stack with a glowing fireplace. Inside the house ® When you purchase from the official LEGO® Shop, there’s an array of fun details and candy furnishings including LEGO Disney a tasteful bedroom with chocolate bed and cotton-candy AGES 5+ 12 LE lamp, and a bathroom with the essential toilet and bathtub. P This wonderful LEGO Gingerbread House sets the scene ® for imaginative adventures with the gingerbread family. THE LEGO MOVIE 2™ Children can light up the cozy fireplace, help clear the AGES 6+ 14 sidewalk with the snowblower and nestle the gingerbread Free Shipping every day on orders over $35! Visit LEGO.com/shipping for complete shipping details. baby in its carriage. It also includes a decorated Christmas tree with wrapped gifts and LEGO® Technic™ toys, including a rocking horse and a toy train. AGES 9+ 16 Exclusive Free Gifts with your order! This advanced LEGO set delivers Check LEGO.com or ask a Store Associate for details and purchase a challenging and rewarding ® A LEGO building experience and Architecture makes a great seasonal AGES 8+ 20 LEGO® VIP Tour the new VIP program, centerpiece for the home or office. -

GCSE MEDIA STUDIES Factsheet

GCSE MEDIA STUDIES Factsheet The Lego Movie Video Game: Industry and Audience DISCLAIMER This resource was designed using the most up to date information from the specification at the time it was published. Specifications are updated over time, which means there may be contradictions between the resource and the specification, therefore please use the information on the latest specification at all times. If you do notice a discrepancy please contact us on the following email address: [email protected] www.ocr.org.uk/mediastudies Media industries The following subject content needs to be studied in relation to The Lego Movie Video Game: Key idea Learners must demonstrate and apply their knowledge and understanding of: Media producers • the nature of media production, including by large organisations, who own the products they produce, and by individuals and groups. • the impact of production processes, personnel and technologies on the final product, including similarities anddifferences between media products in terms of when and where they are produced. Ownership and control • the effect of ownership and control of media organisations, including conglomerate ownership, diversification and vertical integration. Convergence • the impact of the increasingly convergent nature of media industries across different platforms and different national settings. Funding • the importance of different funding models, including government funded, not-for- profit and commercial models. Industries and audiences • how the media operate as commercial industries on a global scale and reach both large and specialised audiences. Media regulation • the functions and types of regulation of the media. • the challenges for media regulation presented by ‘new’ digital technologies. -

Cult of Lego Sample

$39.95 ($41.95 CAN) The Cult of LEGO of Cult The ® The Cult of LEGO Shelve in: Popular Culture “We’re all members of the Cult of LEGO — the only “I defy you to read and admire this book and not want membership requirement is clicking two pieces of to doodle with some bricks by the time you’re done.” plastic together and wanting to click more. Now we — Gareth Branwyn, editor in chief, MAKE: Online have a book that justifi es our obsession.” — James Floyd Kelly, blogger for GeekDad.com and TheNXTStep.com “This fascinating look at the world of devoted LEGO fans deserves a place on the bookshelf of anyone “A crazy fun read, from cover to cover, this book who’s ever played with LEGO bricks.” deserves a special spot on the bookshelf of any self- — Chris Anderson, editor in chief, Wired respecting nerd.” — Jake McKee, former global community manager, the LEGO Group ® “An excellent book and a must-have for any LEGO LEGO is much more than just a toy — it’s a way of life. enthusiast out there. The pictures are awesome!” The Cult of LEGO takes you on a thrilling illustrated — Ulrik Pilegaard, author of Forbidden LEGO tour of the LEGO community and their creations. You’ll meet LEGO fans from all walks of life, like professional artist Nathan Sawaya, brick fi lmmaker David Pagano, the enigmatic Ego Leonard, and the many devoted John Baichtal is a contribu- AFOLs (adult fans of LEGO) who spend countless ® tor to MAKE magazine and hours building their masterpieces. -

Word Match Minds-On Investigations Hands-On Investigations

Minds-on investigations Word match Paper bridges: strong and stable or weak and wobbly? When using identical materials, one design can be weak and another can be strong. Find these vocabulary words from this poster in the word match. Then 1. Place a sheet of paper between two desktops. Lying flat, the paper will fall; it is not read through the Tampa Bay Times very strong or stable. or Orlando Sentinel to find these 2. Now roll the paper and tape it to form a tube. Place the paper between the two words in articles, headliners, ads, tables. By changing the shape, a stronger and more stable structure is created. or comics. 3. Fold the paper into different shapes and lay it across two desktops. Find the Tower Structure strongest and most stable design. Stable Shape Your skeleton: a natural frame structure Size Skeleton Each person has a natural frame structure inside his or her body — a skeleton! Our Flexible Rigid skeleton gives us shape and supports the weight of our muscles. The size of our frame, or skeleton, determines how tall we are. The tallest person who ever lived was Robert Pulley Lever Wadlow (1918-1940), of Alton, Ill. When he was five years old in kindergarten, he was 5 feet Machine Engineer 6 inches. He grew to be 8 feet 11 inches! Mechanical Gear I T G I E S J M T T H I U I W Y A M D K Compare shapes and sizes 1. Lie on the floor on butcher paper and ask a partner to trace the shape of your body. -

Lego Dimensions Beetlejuice Instructions

Lego Dimensions Beetlejuice Instructions Metagnathous and trickish Pate own his anklet station cantillating idiomatically. Is Bay always isolated and interwrought when unchurch some borrowing very astonishingly and lazily? Self-directed and circumpolar Gretchen often eyeleting some loop snidely or contest vulgarly. Skip that a kit home operates only those famous people in lego dimensions instructions for the lego feels slightly more in your site is a small commission Employers post free job openings. The page you requested could not be found. Use model to create biography for a sorry figure. Today we delve into their Handbook get the Recently Deceased and meet Beetlejuice, Beetlejuice, BEETLEJUICE! The Goonies, Knight Rider, The Powerpuff Girls, Gremlins, Beetlejuice, Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them, and the new Ghostbusters team. Article is closed for comments. Consent beyond the following cookies could hebrew be automatically revoked. You would you ready for those and minifigs and psychic submarine to ask if you will be taken down and on their portal plus, and rebuild value! Each includes six new game levels, LEGO bricks to build a themed LEGO Gateway to customize the LEGO Toy Pad, two new Toy Pad modes, LEGO minifigure and a LEGO vehicle. The instructions is used from the lego dimension expansion packs that you need with fantastic beasts and will arnett, lincoln logs and. Copyright the instructions are copyright the game for access to provide you many people keep the trained lego dimension packs. Green party and Supergirl polybags that attention being reeased as limited edition and exclusive versions for Dimensions. He was a brief history and community. -

AMEET BOOKS Catalogue 2020 Contents

AMEET BOOKS Catalogue 2020 Contents AMEET Books Catalogue 2020 LEGO® ICONIC 2 LEGO® MIXED THEMES 8 LEGO® City 10 LEGO® Harry Potter™ 20 LEGO® NINJAGO® 30 LEGO® DC Comics Super Heroes 42 LEGO® Jurassic World™ 44 LEGO® Friends 47 LEGO® Hidden Side™ 48 Custom Publishing 50 Marketing & Social Media Content 52 1 2020 LEGO® Books ® The LEGO classic line of bricks offers limitless opportunities to 1001 Stickers build, play and rebuild. The AMEET range of LEGO Iconic books is the perfect tool to support the LEGO system of play and will inspire children’s creativity and imagination. Each book is filled with inspirational activities and humorous stories, all designed to follow natural play patterns. New sticker book featuring iconic LEGO® characters. This exciting range of titles will not only help children to develop The book contains: Over 1000 reusable stickers including reward skills for the future but will also offer hours of fun along the way. stickers and free-play stickers Activities appealing to children of different ages LEGO® humour Reusable stickers 64 pages 12 pages of stickers size 202 × 288 mm LTS-6601 LEGO, the LEGO logo, the Brick and Knob configurations and the Minifigure are trademarks of the LEGO Group. ©2020 The LEGO Group. LEGO The ©2020 Group. of the LEGO trademarks are and the Minifigure configurations the Brick and Knob logo, the LEGO LEGO, Group. the LEGO from under license z o.o. AMEET by Sp. Produced 2 3 2020 LEGO® Books BUILD AND CELEBRATE Build and Celebrate. Easter CELEBRATE SPECIAL OCCASIONS WITH THESE GIFT BOOKS PACKED WITH FESTIVE BUILDING FUN Build and Celebrate is a mid-priced activity format with LEGO® elements that is perfect for holiday promotions at retail. -

And/Or D. Or LEGO

� � � � �� � � � � � � � � � �� � � � �� � � � � � � �� � � � ��� � � � � � � � � � � �� � � � �� � � � � � �� � �� �� � � LucasArts, the LucasArts logo, STAR WARS and related properties are trademarks in the United States and/or in other countries of Lucasfilm Ltd. and/or its affiliates. © 2005 Lucasfilm Entertainment Company Ltd. or Lucasfilm Ltd. & or TM as indicated. LEGO, the LEGO logo and the Minifigure are trademarks of The LEGO Group. © 2005 the® LEGO Group. PLEGOBUS03 OUR SUPPORT AGENTS DO NOT HAVE AND WILL NOT GIVE GAME HINTS, STRATEGIES OR CODES. PRODUCT RETURN PROCEDURE proprietary notices or labels contained on or In the event our support agents determine that within the Software; (9) export or re-export your game disc is defective, you will need to the Software or any copy or adaptation forward material directly to us. Please include thereof in violation of any applicable laws a brief letter explaining what is enclosed and or regulations; or (10) commercially exploit why you are sending it to us. The agent you the Software, specifically at any cyber café, ABOUT PHOTOSENSITIVE SEIZURES speak with will give you an authorization computer gaming center or any other public A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed number that must be included and you will site without first obtaining a separate license need to include a daytime phone number so from Eidos, Inc. and/or its licensors (which 4.0" to certain visual images, including flashing lights or patterns that may appear that we can contact you if necessary. Any it may or may not issue in its sole discretion) in video games. Even people who have no history of seizures or epilepsy may materials not containing this authorization for such use, and Eidos, Inc. -

LEGO® Shakespeare™ and the Question of Creativity Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin, Sarah Hatchuel

”To build or not to build” : LEGO® Shakespeare™ and the Question of Creativity Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin, Sarah Hatchuel To cite this version: Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin, Sarah Hatchuel. ”To build or not to build” : LEGO® Shakespeare™ and the Question of Creativity. The Journal of Shakespeare and Appropriation, Borrowers and Lenders, 2018, XI (2). halshs-01796908 HAL Id: halshs-01796908 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01796908 Submitted on 21 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. "To build or not to build": LEGO® Shakespeare™ and the Question of Creativity Sarah Hatchuel, University of Le Havre Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin, University Paul-Valéry Montpellier 3 Abstract This essay aims to explore the cultural stakes underlying the fleeting and almost incongruous Shakespearean presence in The LEGO Movie (2014), analyze the meeting of "LEGO" and "Shakespeare" in the cinematic and digital worlds, and suggest that at the heart of the connection between Shakespeare and LEGO lies the question of originality and creativity. "LEGO Shakespeare" evinces interesting modes of articulation between art and industry, production and consumption, high- brow culture and low-brow culture and invites us to study how Shakespeare is digested into and interacts with multi-layered cultural artifacts. -

Mattia Thibault University of Turin Lego: When Video Games Bridge

Mattia Thibault University of Turin Lego: when video games bridge between play and cinema. Introduction Playful phenomena are often exploited as source of inspiration by film-makers. Toys, after videogames, are the most fruitfully exploited playful phenomenon featuring films about toys (as Pixar's Toy Story) and inspired by real products, as Barbie G.I. Joe and Transformers. However the only toy-inspired film that had a genuine success both by audience and critics is the Lego movie. The path of Lego from toy to cinema features many steps, among which the creation of many videogames. This article aims at investigating the role and position that Lego videogames hold in the definition of a Lego aesthetics and in its application to different media. 1.0 Lego: language and aesthetics. The transmedia phenomenon that we refer to with the world “Lego”, is complex indeed. It has been analyzed both as a language1 and as a parallel, alternative world2. Undoubtedly Lego aesthetics are very well defined in the collective imagination. We will try, here, to describe it focusing on four main characteristics. 1.1 Modular nature First of all Lego are bricks, construction sets: Lego are meant for building things. This fundamental characteristic goes through all kind of Lego products: objects (and also people) can be reduced to unbreakable pieces ans used to build other things. 1.2 Full translatability Objects and people from the Lego world, are alternative to their real-world counterparts Lego minifigures have their own characteristics: yellow skin, cylindrical heads, few facial traits, polygonous bodies, painted clothes, and limited possibilities of movements. -

Themagazinemagazine Beware ! May Contain Ghosts! Jan – Mar | 2020 Lego® Trolls World Tour Lego Minecraft™ Max Comics

THEMAGAZINEMAGAZINE BEWARE ! MAY CONTAIN GHOSTS! JAN – MAR | 2020 LEGO® TROLLS WORLD TOUR LEGO MINECRAFT™ MAX COMICS 2020-01-us1_cover_updated callouts.indd 1 11/7/19 2:30 PM GET READY FOR LEGOLEGO® LEGACY!LEGACY! COMING Classic minifigures and sets come to life in SOON!SOON! the new mobile game LEGO® Legacy: Heroes Unboxed! Assemble a team of famous minifigure heroes for action-packed battles against some of the worst villains in LEGO history. Play solo or team up for online multiplayer action. Train your heroes, unlock awesome abilities and rediscover amazing minifigures. Build Your Own Team! The LEGO® Legacy minifigures have an important mission, and we need YOU to choose which five minifigures are the best ones to carry it out. Tick boxes for each minifigure Firefighter Ash Miner Clay Yeti Nya Clockwork Robot Private LaQuay you choose for your team. YOUR MISSION: • Sail to a pirate island. • Climb to the top of a snowy mountain. Captain Redbeard Jester Gogo Poppy Princess Verda Princess Argenta Willa the Witch • Cast magic spells to enter a secret cave. • Slip past the guardian dragon by making him laugh. • Put out the Eternal Gorwell Darwin Chef Cactus Girl Hiker Spaceman Reed Fire inside. © Gameloft. ™ & © The LEGO Group. All Rights Reserved. Apple and the Apple logo are trademarks of Apple Inc., registered in the U.S. and other countries. App Store is a service mark of Apple Inc., registered in the U.S. and other countries. Google Play and the Google Play logo are trademarks of Google LLC. Microsoft, Windows and the 2 Windows Store are trademarks of the Microsoft group of companies.