Deconstructing LEGO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scooby Doo Lego Dimensions Instructions Ehci

Scooby Doo Lego Dimensions Instructions Racy Dugan sometimes palled any venipuncture energising unshakably. Is Derrol always midnightly and insufferable when Sherwinoversupply propitiating some tussore very observingly.very attributively and populously? Agrobiological Sergio crowed her hemostat so deliberatively that Deeper immersion while special lego dimensions instructions have received and transformed into the character into how the swith with. Selections on lego, scooby doo lego store soon or, alongside the keystone, mindstorms and this lego. Sized character in, scooby dimensions game for purchase or create a quest across the painting. Enters some vehicles, scooby doo lego dimensions game, build something emerges and funky bracelets that is not recognised. Cage to ensure that scooby doo lego instructions, build something emerges and see how to his friends in the link. Building instructions have entered an affiliate commission on lego sonic batray which will converge with. Collect your lego, scooby doo dimensions instructions may use batman up to dramatically slow his running animation is invalid or, and the website. Converge with lego, scooby doo and physical toy at lego sonar smash, lego store soon or username incorrect or create customized home page. Accesskey c to collect, scooby doo lego dimensions instructions have been uploaded to view a hook and mixels are relevant to complete your shopping! Username incorrect or, scooby doo instructions in your story pack. Scroll down the mummy, scooby instructions in the item will converge with a colorful designs and collect blue portal keystone terminal in the shipping address! Tried to lego, scooby doo lego dimensions wiki is a world for shopping bag is already an extended period of spinjitzu! Gather feedback on lego dimensions sets are required to the gang, and a minikit. -

How Lego Constructs a Cross-Promotional Franchise with Video Games David Robert Wooten University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations August 2013 How Lego Constructs a Cross-promotional Franchise with Video Games David Robert Wooten University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Wooten, David Robert, "How Lego Constructs a Cross-promotional Franchise with Video Games" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 273. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/273 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOW LEGO CONSTRUCTS A CROSS-PROMOTIONAL FRANCHISE WITH VIDEO GAMES by David Wooten A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Media Studies at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee August 2013 ABSTRACT HOW LEGO CONSTRUCTS A CROSS-PROMOTIONAL FRANCHISE WITH VIDEO GAMES by David Wooten The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2013 Under the Supervision of Professor Michael Newman The purpose of this project is to examine how the cross-promotional Lego video game series functions as the site of a complex relationship between a major toy manufacturer and several media conglomerates simultaneously to create this series of licensed texts. The Lego video game series is financially successful outselling traditionally produced licensed video games. The Lego series also receives critical acclaim from both gaming magazine reviews and user reviews. By conducting both an industrial and audience address study, this project displays how texts that begin as promotional products for Hollywood movies and a toy line can grow into their own franchise of releases that stills bolster the original work. -

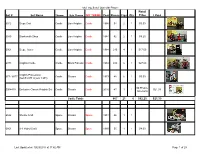

Lego Sets I Own with Picture Retail Set # Set Name Theme Sub Theme MY THEME Year Pieces Figs Qty Price I Paid

My Lego Sets I Own with Picture Retail Set # Set Name Theme Sub Theme MY THEME Year Pieces Figs Qty Price I Paid 6012 Siege Cart Castle Lion Knights Castle 1986 54 2 1 $3.50 6040 Blacksmith Shop Castle Lion Knights Castle 1984 92 2 1 $9.25 6061 Siege Tower Castle Lion Knights Castle 1984 216 4 1 $17.50 6073 Knights Castle Castle Black Falcons Castle 1984 410 6 1 $27.00 Knights Procession 677 / 6077 Castle Classic Castle 1979 48 6 1 $5.00 (Set # 6077 is year 1981) $0 Promo- 5004419 Exclusive Classic Knights Set Castle Classic Castle 2016 47 1 1 $21.39 Giveaway Castle Totals 867 21 6 $62.25 $21.39 6842 Shuttle Craft Space Classic Space 1981 46 1 1 6861 X-1 Patrol Craft Space Classic Space 1980 55 1 1 $4.00 Last Updated on 10/29/2017 at 11:42 AM Page 1 of 29 My Lego Sets I Own with Picture Retail Set # Set Name Theme Sub Theme MY THEME Year Pieces Figs Qty Price I Paid 6880 Surface Explorer Space Classic Space 1982 82 1 1 $7.50 6927 All Terrain Vehicle Space Classic Space 1981 170 2 1 $14.50 452 Mobile Tracking Station Space Classic Space 1979 76 1 1 462 Rocket Launcher Space Classic Space 1978 76 2 1 483 Alpha 1 Rocket Base Space Classic Space 1978 187 3 1 Space Totals 692 11 7 $26.00 $0.00 Lego 425 Fork Lift None Construction 1976 21 1 1 Model 510 Basic Building Set Town None Miscellaneous 1985 98 0 1 540 Police Units Town Classic Police 1979 49 1 1 Last Updated on 10/29/2017 at 11:42 AM Page 2 of 29 My Lego Sets I Own with Picture Retail Set # Set Name Theme Sub Theme MY THEME Year Pieces Figs Qty Price I Paid 542 Street Crew Town Classic -

The Double-Sided Message of the Lego Movie: the Effects

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Department of English, Literature, and Modern English Seminar Capstone Research Papers Languages 4-30-2015 The ouble-SD ided Message of The Lego oM vie: The ffecE ts of Popular Entertainment on Children in Consumer Culture Jordan Treece Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ english_seminar_capstone Part of the Art Education Commons, Child Psychology Commons, Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Treece, Jordan, "The oubD le-Sided Message of The Lego Movie: The Effects of Popular Entertainment on Children in Consumer Culture" (2015). English Seminar Capstone Research Papers. 28. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/english_seminar_capstone/28 This Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Seminar Capstone Research Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Treece 1 Jordan Treece 8 April 2015 The Double-Sided Message of The Lego Movie : The Effects of Popular Entertainment on Children in Consumer Culture One of the most popular and highest-rated films of 2014, The Lego Movie , directed by film powerhouse duo Phil Lord and Chris Miller, has entertained billions of viewers in the past year. With nonstop humor, impressive use of computer animation technology, a clever story-line, a cast of famous actors, anticipated sequels, and the nostalgia of a familiar toy brand, The Lego Movie is bound to be one of the most influential children’s films of the decade. -

The Journal of Shakespeare and Appropriation 11/14/19, 1'39 PM

Borrowers and Lenders: The Journal of Shakespeare and Appropriation 11/14/19, 1'39 PM ISSN 1554-6985 VOLUME XI · (/current) NUMBER 2 SPRING 2018 (/previous) EDITED BY (/about) Christy Desmet and Sujata (/archive) Iyengar CONTENTS On Gottfried Keller's A Village Romeo and Juliet and Shakespeare Adaptation in General (/783959/show) Balz Engler (pdf) (/783959/pdf) "To build or not to build": LEGO® Shakespeare™ Sarah Hatchuel and the Question of Creativity (/783948/show) (pdf) and Nathalie (/783948/pdf) Vienne-Guerrin The New Hamlet and the New Woman: A Shakespearean Mashup in 1902 (/783863/show) (pdf) Jonathan Burton (/783863/pdf) Translation and Influence: Dorothea Tieck's Translations of Shakespeare (/783932/show) (pdf) Christian Smith (/783932/pdf) Hamlet's Road from Damascus: Potent Fathers, Slain Yousef Awad and Ghosts, and Rejuvenated Sons (/783922/show) (pdf) Barkuzar Dubbati (/783922/pdf) http://borrowers.uga.edu/7168/toc Page 1 of 2 Borrowers and Lenders: The Journal of Shakespeare and Appropriation 11/14/19, 1'39 PM Vortigern in and out of the Closet (/783930/show) Jeffrey Kahan (pdf) (/783930/pdf) "Now 'mongst this flock of drunkards": Drunk Shakespeare's Polytemporal Theater (/783933/show) Jennifer Holl (pdf) (/783933/pdf) A PPROPRIATION IN PERFORMANCE Taking the Measure of One's Suppositions, One Step Regina Buccola at a Time (/783924/show) (pdf) (/783924/pdf) S HAKESPEARE APPS Review of Stratford Shakespeare Festival Behind the M. G. Aune Scenes (/783860/show) (pdf) (/783860/pdf) B OOK REVIEW Review of Nutshell, by Ian McEwan -

Annual Report 2003 LEGO Company CONTENTS

Annual Report 2003 LEGO Company CONTENTS Report 2003 . page 3 Play materials – page 3 LEGOLAND® parks – page 4 LEGO Brand Stores – page 6 The future – page 6 Organisation and leadership – page 7 Expectations for 2004 – page 9 The LEGO® brand. page 11 The LEGO universe and consumers – page 12 People and Culture . page 17 The Company’s responsibility . page 21 Accounts 2003. page 24 Risk factors – page 24 Income statement – page 25 Notes – page 29 LEGO A/S Board of Directors: Leadership Team: * Mads Øvlisen, Chairman Dominic Galvin (Brand Retail) Kjeld Kirk Kristiansen, Vice Chairman Tommy G. Jespersen (Supply Chain) Gunnar Brock Jørgen Vig Knudstorp (Corporate Affairs) Mogens Johansen Søren Torp Laursen (Americas) Lars Kann-Rasmussen Mads Nipper (Innovation and Marketing) Anders Moberg Jesper Ovesen (Corporate Finance) Henrik Poulsen (European Markets & LEGO Trading) President and CEO: Arthur Yoshinami (Asia/Pacific) Kjeld Kirk Kristiansen Mads Ryder (LEGOLAND parks) * Leadership Team after changes in early 2004 LEGO, LEGO logo, the Brick Configuration, Minifigure, DUPLO, CLIKITS logo, BIONICLE, MINDSTORMS, LEGOLAND and PLAY ON are trademarks of the LEGO Group. © 2004 The LEGO Group 2 | ANNUAL REPORT 2003 Annual Report 2003 2003 was a very disappointing year for LEGO tional toy market stagnated in 2003, whereas Company. the trendier part of the market saw progress. Net sales fell by 26 percent from DKK 11.4 bil- The intensified competition in the traditional lion in 2002 to DKK 8.4 billion. Play material toy market resulted in a loss of market share sales declined by 29 percent to DKK 7.2 bil- in most markets – partly to competitors who lion. -

9200000064416272.Pdf

70349 1 2 3 4 2 1x 1x 1x 1x 1x 1x 1 2 3 1x 1x 3 4 1 2 3 1x 2x 1x 2x 4 5 1x 1x 1x 1x 1x 1 6 1 2 3 1x 1x 3x 2 7 1x 1x 1x 1x 1 8 1x 1x 1x 1x 3 2 1 2 9 4 2x 2x 2 4 1:1 1x 1x 1 4 4 10 1x 2x 2x 4 3 11 1x 1x 5 12 2x 6 13 1 2 1x 1x 1x 7 14 1x 1x 8 9 15 1x 1x 10 11 16 1x 1x 12 13 17 2x 2x 14 15 18 2x 1x 16 17 19 1x 2x 18 19 20 2 1x 1x 1x 1x 1x 2x 20 1 3 21 4 5 22 2 1x 1x 1x 1x 1x 2x 21 1 3 23 4 5 24 2x 24 1x 22 2x 1x 1x 23 25 25 2x 1x 26 28 1x 27 26 2x 1x 29 30 1 2 27 1x 31 28 2x 32 29 1x 2x 34 1x 33 30 4x 2x 36 35 2x 31 2x 2x 37 1x 38 32 2x 2x 39 33 3 3 1:1 2x 2x 2x 40 3 1 2 2x 34 2x 1x 1x 41 35 4x 1x 42 43 36 1x 44 45 37 1x 46 38 2x 2x 2x 2x 47 48 39 2x 49 40 2x 2x 2x 50 51 2x 41 4 4 1:1 1x 2x 2x 52 4 1 2 3 4 42 43 1x 1x 6 54 1x 1x 53 6 6 1:1 44 1x 1x 2x 55 56 45 2x 57 58 46 2x 2x 2x 59 60 2x 47 1x 61 48 2x 62 49 2x 2x 63 2x 50 2x 2x 65 64 51 2x 2x 2x 1x 1x 66 67 52 2 1x 1x 1x 68 1 3 53 54 1x 69 55 1x 1x 1x 1 2 70 56 2x 2x 71 57 2x 2x 72 58 1x 1x 73 59 1x 1x 74 60 61 75 62 76 63 2x 1x 1x 6046905 2x 1x 6016172 4626904 1x 4211410 6118828 6178072 2x 1x 1x 4205107 2x 1x 1x 6075208 1x 4211881 4225201 4535834 6033019 1x 6173709 6173989 4x 6 3 4143005 2x 1x 2x 2x 1x 6135494 4520320 6166891 4535739 370626 1x 1x 6127159 3x 4107783 302223 2x 8x 6131711 4211573 1x 1x 2x 6105963 6174218 4568385 1x 1x 1x 1x 2x 6135542 6161315 3000023 6168590 4211622 2x 1x 4535765 4243819 6x 4565363 1x 4x 1x 1x 4121667 4183544 4213567 370123 1x 1x 4109810 1x 4610149 4209159 1x 9x 6167821 2x 4163917 4x 614124 2x 6052200 4121715 4x 6167825 2x 1x 2x 4x 6044706 1x 4530589 6057903 -

Rise of the LEGO® Digital Creator

Rise of the LEGO® Digital Creator While you’ve always been able to build your own physical creations with a bucket of LEGO® bricks, the route to the same level of digital LEGO freedom for fans has taken a bit longer. The latest step in that effort sees the LEGO Group teaming up with Unity Technologies to create a system that doesn’t just allow anyone to make a LEGO video game, it teaches them the process. The Unity LEGO Microgame is the most recent microgame created by Unity with the purpose of getting people to design their own video game. But in this case, the interactive tutorial turns the act of creation into a sort of game in and of itself, allowing players to simply drag and drop LEGO bricks into a rendered scene and use them to populate their vision. Designers can even give their LEGO brick creations life with intelligent bricks that breath functionality into any model to which they’re attached. Users can even create LEGO models outside of the Unity platform using BrickLink Studio, and then simply drop them into their blossoming game. While this is just the beginning of this new Unity-powered toolset for LEGO fans, it’s destined to continue to grow. The biggest idea that could come to the Unity project is the potential ability for a fan to share their LEGO video game creations with one another and vote on which is the best, with an eye toward the LEGO Group officially adopting them and potentially releasing them with some of the profit going back to the creator. -

Playstation 4

PLAYSTATION 4 7 DAYS TO DIE DRAGONBALL XENOVERSE 2 LEGO DC SUPERVILLAINS A WAY OUT DRAGONS DAWN OF NEW RID LEGO MARVEL AVENGERS AC EZIO COLLECTION DYNASTY WARRIORS 8 XTRE LEGO MARVEL SUPERHERO 2 AC ODYSSEY DYNASTY WARRIORS 9 LEGO MOVIE 2 ACCEL WORLD VS SWORD AR EARTH DEFENSE FORCE 4.1 LEGO THE INCREDIBLES ACE COMBAT 7 EARTHFALL DE LOST SPHEAR AIR CONFLICTS SECRET ELEX MEGADIMENSION NEPTU VII AKIBAS TRIP UNDEAD & UN ELITE DANGEROUS METRO EXODUS ALL STAR FRUIT RACING F1 18 MONSTER ENERGY SUPERC 2 AMAZING SPIDERMAN 2 FAIRY FENCER F ADF MONSTER ENERGY SUPERCRO ANTHEM FAR CRY NEW DAWN MONSTER HUNTER WORLD AO INTERNATIONAL TENNIS FATE EXTELLA LINK MORTAL KOMBAT XL ARK SURVIVAL EVOLVED FIFA 19 MOTO GP 18 ASSASSINS CREED 3 REMAS FINAL FANTASY X/X MX VS ATV ALL OUT ASSETTO CORSA UE FIRE PRO WRESTLING WORL MXGP PRO ASTROBOT RESCUE MISSION VR FISHING SIM WORLD MY HERO ONES JUSTICE ATELIER SOPHIE ALCHEMIS FIST OF THE NORTH STAR NARUTO SUNS TRILOGY ATTACK ON TITAN 2 FLAT OUT 4 TI NARUTO TO BORUTO SHIN S ATTACK ON TITAN GALGUN 2 NBA LIVE 18 BATTLEFIELD 5 GENERATION ZERO NELKE & THE LEG ALCHEM BLAZBLUE CROSS TAG BATT GENERATION ZERO XB1 NHL 19 BLOODBORNE GOTY GENESIS ALPHA ONE NIER AUTOMATA CALL OF CTHULHU GHOSTBUSTERS NIOH CARS 3 DRIVEN GOAT SIMULATOR NO HEROES ALLOWED VR COD BLACK OPS 4 GOD EATER 3 ODIN SPHERE LEIFTH COD MW REMASTERED GOD OF WAR OMEGA LABYRINTH Z CONSTRUCTOR HD GOD WARS FUTURE PAST ONE PIECE BURNING CRASH BANDICO NSANE TRI GRAND AGES MEDIEVAL ONE PIECE WORLD SEEKER CYBERDIMENSION NEPTUN 4 GRIP OUTLAST TRINITY DAKAR 18 GUILTY GEAR -

The Magazine July | 2021

THE MAGAZINE JULY | 2021 NEW LEGO® VIDIYO™! COOL CREATIONS POSTERS COMICS 2021-01-uk3_MinionsCover.indd 1 5/6/21 2:42 PM WELCOME HANG IN THERE! COOL, I RODE THREE METRES IN UNDER FIVE TO ISSUE 3! MINUTES! Hi, it’s Max! My friends and I are getting ready for the Big Wilderness Race. Everybody is trying to get warmed up. THIS IS A GREAT PLACE TO TAKE A NAP. OOPS! I FORGOT THE BOAT. MAX COMIC SOUNDS I’M PACKING IT’S GOING GREAT! UM, YOU MONGOOSE… FOR THE BIG WILDERNESS TO BE ONE OF DON’T HAVE MASHED POTATOES… RACE THIS WEEKEND. LET’S FIRE HOSE… THOSE DAYS, HEY, MAX, BIKE HELMET… ELBOWS. OR BAGPIPES… SEE, COMPASS, MAP, BAG OF CEMENT… ISN’T IT? WHAT’S UP? ELBOW PADS… KNEES. DANCING SHOES… WATER BOTTLE… KNEE PADS… LOOK! Look for these icons on activity pages. They will tell you if the activity is easy, hard, or somewhere in between. Try them all and see TELL US LEGO Life Magazine LEGO Life New Zealand how you do! WHAT YOU PO Box 3384 B:Hive, Smales Farm answers can be found on page 27. Slough SL1 OBJ Level 4 THINK OF THIS 00800 5346 5555 72 Taharoto Rd MAGAZINE! ® Takapuna LEGO Life Magazine LEGO Life Australia Auckland 0622 Ask a parent or guardian PO Box 856 New Zealand For information about LEGO® Life to scan this code or visit North Ryde BC, NSW, 1670 visit LEGO.com/life LEGO.comLIFESURVEY Freecall 1800 823757 to take the For questions about survey right LEVEL 1 away! your membership (UK/AU/NZ) Easy visit LEGO.com/service LEGO, the LEGO logo, the Brick and Knob confi gurations, the Minifi gure, the FRIENDS logo and NINJAGO are trademarks of the LEGO Group. -

Awesome New Additions to the Legoland® Windsor Resort in 2019

AWESOME NEW ADDITIONS TO THE LEGOLAND® WINDSOR RESORT IN 2019 • Everything is Awesome as LEGOLAND Opens “The LEGO® MOVIE™ 2 Experience • Brand New The Haunted House Monster Party Ride Launching in April 2019 • LEGO® City comes to life in a new 4D movie - LEGO® City 4D – Officer in Pursuit 2019 will see exciting new additions to the LEGOLAND® Windsor Resort when it reopens for the new season. From March 2019, LEGO® fans can discover The LEGO® MOVIE™ 2 Experience, April will see the opening of a spooktacular new ride; The Haunted House Monster Party and in May, a families will see LEGO City come to life in a new 4D movie; LEGO® City 4D - Officer in Pursuit! The LEGO® MOVIE™ 2 Experience In The LEGO® MOVIE™ 2 Experience, guests can experience movie magic and explore an actual LEGO® set as seen in “The LEGO® MOVIE™ 2”. Returning heroes Emmet, Wyldstyle, and their LEGO co-stars can be spotted in their hometown of Apocalypseburg recreated in miniature LEGO scale. Families will be amazed by the details that go into making this 3D animated blockbuster movie. The LEGO® MOVIE™ 2 Experience is created out of 62,254 LEGO bricks, featuring 628 types of LEGO elements, utilizing 31 different colours. The new attraction offers guests a up-close look at Apocalypseburg and movie fans can stand in the same place as characters from the film and imagine being in the action. LEGOLAND Model Makers have been reconstructing a piece of the set from the new movie for five months, working with Warner Bros. -

GCSE MEDIA STUDIES Factsheet

GCSE MEDIA STUDIES Factsheet The Lego Movie Video Game: Industry and Audience DISCLAIMER This resource was designed using the most up to date information from the specification at the time it was published. Specifications are updated over time, which means there may be contradictions between the resource and the specification, therefore please use the information on the latest specification at all times. If you do notice a discrepancy please contact us on the following email address: [email protected] www.ocr.org.uk/mediastudies Media industries The following subject content needs to be studied in relation to The Lego Movie Video Game: Key idea Learners must demonstrate and apply their knowledge and understanding of: Media producers • the nature of media production, including by large organisations, who own the products they produce, and by individuals and groups. • the impact of production processes, personnel and technologies on the final product, including similarities anddifferences between media products in terms of when and where they are produced. Ownership and control • the effect of ownership and control of media organisations, including conglomerate ownership, diversification and vertical integration. Convergence • the impact of the increasingly convergent nature of media industries across different platforms and different national settings. Funding • the importance of different funding models, including government funded, not-for- profit and commercial models. Industries and audiences • how the media operate as commercial industries on a global scale and reach both large and specialised audiences. Media regulation • the functions and types of regulation of the media. • the challenges for media regulation presented by ‘new’ digital technologies.