A Stitch in Time: New Embroidery, Old Fabric, Changing Values

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Machine Embroidery Threads

Machine Embroidery Threads 17.110 Page 1 With all the threads available for machine embroidery, how do you know which one to choose? Consider the thread's size and fiber content as well as color, and for variety and fun, investigate specialty threads from metallic to glow-in-the-dark. Thread Sizes Rayon Rayon was developed as an alternative to Most natural silk. Rayon threads have the soft machine sheen of silk and are available in an embroidery incredible range of colors, usually in size 40 and sewing or 30. Because rayon is made from cellulose, threads are it accepts dyes readily for color brilliance; numbered unfortunately, it is also subject to fading from size with exposure to light or frequent 100 to 12, laundering. Choose rayon for projects with a where elegant appearance is the aim and larger number indicating a smaller thread gentle care is appropriate. Rayon thread is size. Sewing threads used for garment also a good choice for machine construction are usually size 50, while embroidered quilting motifs. embroidery designs are almost always digitized for size 40 thread. This means that Polyester the stitches in most embroidery designs are Polyester fibers are strong and durable. spaced so size 40 thread fills the design Their color range is similar to rayon threads, adequately without gaps or overlapping and they are easily substituted for rayon. threads. Colorfastness and durability make polyester When test-stitching reveals a design with an excellent choice for children's garments stitches so tightly packed it feels stiff, or other items that will be worn hard stitching with a finer size 50 or 60 thread is and/or washed often. -

Powerhouse Museum Lace Collection: Glossary of Terms Used in the Documentation – Blue Files and Collection Notebooks

Book Appendix Glossary 12-02 Powerhouse Museum Lace Collection: Glossary of terms used in the documentation – Blue files and collection notebooks. Rosemary Shepherd: 1983 to 2003 The following references were used in the documentation. For needle laces: Therese de Dillmont, The Complete Encyclopaedia of Needlework, Running Press reprint, Philadelphia, 1971 For bobbin laces: Bridget M Cook and Geraldine Stott, The Book of Bobbin Lace Stitches, A H & A W Reed, Sydney, 1980 The principal historical reference: Santina Levey, Lace a History, Victoria and Albert Museum and W H Maney, Leeds, 1983 In compiling the glossary reference was also made to Alexandra Stillwell’s Illustrated dictionary of lacemaking, Cassell, London 1996 General lace and lacemaking terms A border, flounce or edging is a length of lace with one shaped edge (headside) and one straight edge (footside). The headside shaping may be as insignificant as a straight or undulating line of picots, or as pronounced as deep ‘van Dyke’ scallops. ‘Border’ is used for laces to 100mm and ‘flounce’ for laces wider than 100 mm and these are the terms used in the documentation of the Powerhouse collection. The term ‘lace edging’ is often used elsewhere instead of border, for very narrow laces. An insertion is usually a length of lace with two straight edges (footsides) which are stitched directly onto the mounting fabric, the fabric then being cut away behind the lace. Ocasionally lace insertions are shaped (for example, square or triangular motifs for use on household linen) in which case they are entirely enclosed by a footside. See also ‘panel’ and ‘engrelure’ A lace panel is usually has finished edges, enclosing a specially designed motif. -

Advanced Multi-Needle Embroidery

PR1055X 10-NEEDLE EMBROIDERY . ADVANCED MULTI-NEEDLE EMBROIDERY Experience the Power of 10 • 10 Needles and Large 10.1" Built-in High Definition • Industry-First InnovEye Technology with Virtual LCD Display Design Preview Increase your productivity with 10 needles and stitch designs up to Get a real-time camera view of the needle area and see your 10 colors without changing thread. View your creations in a class- embroidery design on your fabric – no scanning needed! Also, scan leading crisp, vivid color LCD display and navigate easily with the your fabric or garment, preview your design on-screen, and you’re scrolling menu and large, intuitive icons. View 29 built-in tutorial ready to embroider. It works with the optional cap and cylinder videos or MP4 files on-screen. frames for tight spaces. • Brother-Exclusive My Design Center Built-in Software • Wireless LAN Connectivity – My Stitch Monitor Mobile App for Virtually Endless Design Possibilities Keep track of your embroidery with the My Stitch Monitor mobile Draw designs directly onto the screen or use the included scanning app on your iOS or AndroidTM device. Follow the progress of your frame to scan art to embroider. With up to 1600% zoom, view the project and get alerts when it’s time to change threads or when your smallest details of your designs on the LCD display. embroidery is finished. • Add Beautiful Stippling and Decorative Fills • Wireless LAN Connectivity – Link Function Accurately add stippling or echo stitching to any embroidery design, With wireless LAN connectivity and PE-DESIGN 11 software*, you can or save the outline, and then choose from 26 new built-in decorative link as many as 10 machines without a cable. -

1 MULTIUSE, EMBROIDERY and SEWING SCISSORS Stainless Steel

WWW.RAMUNDI.IT GIMAP s.r.l. 23834 PREMANA (LC) ITALY Zona Ind. Giabbio Tel. +39 0341 818 000 The line is composed by extremely high performance items, result of over 70 years of research of perfect cutting performances. Every single item is produced with the best materials and is carefully controlled by the expert hands of our artisans, from the raw material to the last control phase. The Extra line quality will satisfy all your needs. MULTIUSE, EMBROIDERY AND SEWING SCISSORS Stainless steel and handles in nylon 6 Series of professional scissors for textile, embroidery and multipurpose use. Made in AISI 420 steel, these scissors will allow you to made every kind of job with an extreme confort and precision. The scissors are made with special machines that make a perfect finish and operation that lasts over time. Nylon 6 handle are made with fiberglass with an innovative design and it can be use in contact with food. multiuse scissors in stainless steel and handles 553/5 in nylon 6 13 cm 553/6 15 cm 553 552/7,5 19 cm 552/8,5 21 cm 552/9,5 24 cm 552/10,5 26 cm 552/11 28 cm 552M Left- hand 22 cm 552 240/1/3,5 Embroidery scissors 9 cm 241/1/4 Embroidery scissors bent 10 cm 241/1/4 240/1/3,5 351/4 Sewing scissors 10,5 cm 351/5 12,5 cm 351/6 15 cm 351 485/7 Multiuse scissors 19 cm 360MN/4,5 Thread clipper 485/7 360MN/4,5 1 WWW.RAMUNDI.IT GIMAP s.r.l. -

Owl Whipstitch Instructions

Sew Cute Patterns Plush Baby Owl Pattern Whipstitch Tutorial www.sewcutepatterns.com Copyright Sew Cute Patterns Copyright © 2013 by Sew Cute Patterns All rights reserved. No part of this pattern may be reproduced electronically or in print in any form without the written permission of the publisher. Patterns may not be sold or distributed in any manner. Finished sewing projects may be resold by whatever means desired. Your stuffed baby owl will be created with a whipstitch which is done by hand using embroidery floss and a sewing needle. What is a whipstitch? A whipstitch is simply a stitch that passes over the edge of the fabric. Watch a video example at: http://www.sewcutepatterns.com/p/whipstitch.html Begin the whipstitch by tying a knot in the end of the thread. Then poke the needle through the top layer of fabric, about 1/8" in Then go over the edge of the fabric and poke the needle up through both layers of fabric about 1/8" from the edge. The distance between the stitches can vary depending on how you'd like the stitch to look. Generally, about 3/4" or a tab wider is good. Repeat till you get to the end of the fabric you are stitching. Tie a knot to secure. When whipsitching, you want to use a fabric type that won't fray around the edges. Felt fabric is best not only because it doesn't fray but because it doesn't have a lot of pull. So the stitch looks good. Felt however is very limited in colors and patterns and it’s not very soft. -

Gale Owen-Crocker (Ed.), the Bayeux Tapestry. Collected Papers, Aldershot, Hampshire (Ashgate Publishing) 2012, 374 P

Francia-Recensio 2013/1 Mittelalter – Moyen Âge (500–1500) Gale Owen-Crocker (ed.), The Bayeux Tapestry. Collected Papers, Aldershot, Hampshire (Ashgate Publishing) 2012, 374 p. (Variorum Collected Studies Series, CS1016), ISBN 978-1-4094-4663-7, GBP 100,00. rezensiert von/compte rendu rédigé par George Beech, Kalamazoo, MI Scholarly interest in the Bayeux Tapestry has heightened to a remarkable degree in recent years with an increased outpouring of books and articles on the subject. Gale Owen-Crocker has contributed to this perhaps more than anyone else and her publications have made her an outstanding authority on the subject. And the fact that all but three of the seventeen articles published in this collection date from the past ten years shows the degree to which her fascination with the tapestry is alive and active today. Since her own specialty has been the history of textiles and dress one might expect that these articles would deal mainly with the kinds of materials used in the tapestry, the system of stitching, and the like. But this is not so. Although she does indeed treat these questions she also approaches the tapestry from a number of other perspectives. After an eight page introduction to the whole collection the author groups the first three articles under the heading of »Textile«. I. »Behind the Bayeux Tapestry«, 2009. In this article she describes the first examination of the back of the tapestry in 1982–1983 which was accomplished by looking under earlier linings which had previously covered it, and the light which this shed on various aspects of its production – questions of color, type of stitching used, and later repairs. -

Cora Seton's Chance Creek Holiday Cardinal Craft

Cora Seton’s Chance Creek Holiday Cardinal Craft Materials: 1 sheet red felt Scraps of yellow and black felt White embroidery floss Small amount of stuffing—in a pinch, cotton balls or tissues work Directions: A word about embroidery floss: Embroidery floss comes in strands of 6 threads twisted together. When you are ready to sew, you will need to cut a length of the floss and then unwind 1 strand from the other five. Do this slowly and carefully, or your floss will knot up. You will thread that one strand through the needle, even up the two ends, and knot them together—so I sewed with doubled thread for all steps below, which means I cut a piece of floss twice as long as I wanted it to be once I doubled it up. Here’s a video on separating embroidery floss. Note that she cuts a piece pretty short. I did twice as long: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=11_udtynLtg A word about stitching: In the interest of keeping this project as simple as possible, I have chosen fairly straight-forward stitches to use. Please feel free to embellish your project your own way! Get as fancy as you like. I have used the whip stitch and the back stitch: The whip stitch is for joining two edges together. Thread your needle and knot your embroidery floss. Start on the inside of one of the pieces of felt you are sewing together. Run your needle through the felt, match up the edge of your two pieces, run the floss over the top of the edges, and poke the needle through the felt, coming out about an eighth of an inch from the first needle hole. -

The Bayeux Tapestry Embroiderers Story PDF Book

THE BAYEUX TAPESTRY EMBROIDERERS STORY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jan Messent | 112 pages | 01 Jan 2011 | Search Press Ltd | 9781844485840 | English | Tunbridge Wells, United Kingdom The Bayeux Tapestry Embroiderers Story PDF Book Lists with This Book. Oxford University Press. The tapestry is a band of linen feet 70 metres long and Want to Read saving…. Is any historical primary source of information entirely reliable? Richard Burt, University of Florida. Reopening with new conditions: Only the gallery of the Tapestry is open, the interpretation floors remain closed Timetable: 9. The Latin textual inscriptions above the story-boards use Old English letter forms, and stylistically the work has parallels in Anglo-Saxon illuminated manuscripts. What's on? According to Sylvette Lemagnen, conservator of the tapestry, in her book La Tapisserie de Bayeux :. Hearing this news, William decides to cross the Channel in to reclaim his throne…. With a visit to the museum, you can discover the complete Bayeux Tapestry, study it close up without causing damage to it, and understand its history and how it was created thanks to an audio-guide commentary available in 16 languages. Rachelle DeMunck rated it it was amazing Sep 06, Open Preview See a Problem? Heather Cawte rated it it was amazing Apr 05, American historian Stephen D. The design and embroidery of the tapestry form one of the narrative strands of Marta Morazzoni 's novella The Invention of Truth. It required special storage in with the threatened invasion of Normandy in the Franco-Prussian War and again in — by the Ahnenerbe during the German occupation of France and the Normandy landings. -

What Are Fabric Scissors?

What are fabric scissors? Fabric scissors or fabric shears as they are more commonly referred to are the main tool used for cutting out your fabric. There are various different types of fabric shears on the market which range from general purpose to a traditional tailors shears. Shears should cut cleanly and smoothly so the type you choose usually depends on what material you need to cut and what you find comfortable to use. If you are buying hand crafted shears, your choice will also be influenced by the shear manufacturers skill and the quality of steel used. Heavy fabrics such as leather and denim are easier to cut using shears that have longer handles or sharper blades. Synthetic fabrics tend to slip on smooth blades so a serrated pair for better control would be the answer. Elastic or pivoted shears offer precision cutting right to the tip of the blades. Most dressmakers shears are angled (or bent) to keep the blades flat on the table reducing disruption to your lay. But very angled shears can be awkward to use if you need to stretch across a table. Lightweight shears are recommended for occasional use where as drop forged shears are for more prolonged use. The size you choose should depend largely on what you find comfortable to use. If possible try to borrow a pair to handle them and see if they suit you before buying. They mustn’t be to heavy for comfort. If you are in doubt, then go for the larger size. The maintenance of scissors and shears is very important, yet often neglected. -

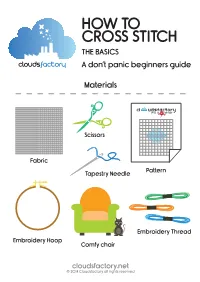

CROSS STITCH the BASICS Cloudsfactory a Don’T Panic Beginners Guide

HOW TO CROSS STITCH THE BASICS cloudsfactory A don’t panic beginners guide Materials cl udsfactory it's a affair Scissors Fabric Pattern Tapestry Needle Embroidery Thread Embroidery Hoop Comfy chair cloudsfactory.net © 2014 Cloudsfactory all rights reserved Thread your needle Your embroidery thread is made up of 6 strands. You will use 1, 2 or 3 strands (de- pending on your fabric count) for cross stitch. Separate your floss and thread your needle with just 2 or 3 strands, your choice! Find the center cl udsfactory it's a affair Find the center of your fabric as well as the center of the pattern. You can fold the fabric in half and then once more in half and place a needle or mark a dot with a water soluble marker in the center of your fabric. Pattern usually have a little black triangle or arrow ( ) that marks the center horizontally and vertically on the top and left of your grid. cloudsfactory.net © 2014 Cloudsfactory all rights reserved Start stitching! Begin by creating a half stitch on the front 2 4 of your work and hold the thread tail behind your work (step 1-2). 1 3 Cross the stitch diagonally to create your first full stitch (step 3-4). Flip your fabric over and pull the tail through the loop. This secures your first stitch! The main goal of neat cross stitching is to have your stitches all face the same direction, so if you have to make a row or more rows of the same color, you have first to complete a row of half stitches, going up at 1, down at 2, up at 3, down at 4, and so on (fig 1). -

Troubleshooting Embroidery Designs Written By: Kay Hickman, BERNINA Educator, Professional & Home Embroidery Specialist

BERNINA eBook Series JUST EMBROIDER IT! Troubleshooting Embroidery Designs Written by: Kay Hickman, BERNINA Educator, Professional & Home Embroidery Specialist Qualities of a Good Design § Maintenance Proper Setup § Problem / Solution Scenarios § Pressing Matters There is nothing quite as satisfying as stitching a perfect embroidery design for that special project. But it can also be frustrating when things go wrong. In order to troubleshoot and fix embroidery design problems, we need to first understand the qualities of a good design and how preventative maintenance can prevent a lot of issues from occurring in the first place. QUALITIES OF A GOOD DESIGN • The fabric is smooth and pucker-free around the outer edges of the design. • There are no traces of the bobbin thread showing on the top side. • There is no gapping between individual elements of a design or between the fill stitches and the design outlines. BACK SIDE • On the back (bobbin) side, you should see the bobbin thread. You should also see the needle threads around the edges of a fill or either side of a column type design. FRONT SIDE MAINTENANCE Preventative maintenance can go a long way to aid in getting a good stitch out. • Clean the machine every 3 to 4 hours of stitching time. This is especially crucial because the high speed of the embroidery creates more lint and fuzz than you encounter during normal sewing. Remove BEFORE HOOK OIL AFTER HOOK OIL all fuzz and check for tiny bits of thread that might • Follow the manufacturer’s suggestions and take be stuck in the bobbin case. -

Pulled Thread (Wrapin Stitch in Diagonal Rows)

PulledWork:aWhiteworkNeedleLaceTechnique ClassforWestKingdomNeedlworkers JuneCrownASXXXVIII bySabrinadelaBere The following project is designed as a sampler of stitches needle lace as it evolves in the 16th century. that have been found in whitework before 1600. The ouline of the design is taken from the example below of a 16th C. Pulled work is the distortion of the warp and weft threads to English pulled work coif and apron. Historically, multiple form patterns. The threads are litereally pulled out of stitches might be used in a piece, but within a single design, alingnment, bound into groups, and otherwise added to cre- it would not be a “sampler” of stitches.. ate patterns. Pulled work was also used to create a back- ground for other embroidery. Both the use of pulled work as Whitework is the pattern maker and as background are illustrated on the a modern term piece below. that refers to embroidery on The examples of whitework that have survived from the 12th, white linen (or 13th, and 14th C are all church linens. Most show what we cotton) and call surface embroidery stitches and some drawn work. One worked with a such example is the Opus Tutonicum (“German Whitework”) white thread that heralds from Lower Saxony in the 13th C. (linen, cotton, silk). There are In the late 15th C whitework, in various forms, is found on many forms of shirts and chemises. A number of European portraits have whitework, but bits of whitework showing around the edges of necklines the form we are and cuffs. It really comes into wide spread use for personal concentrating on here is pulled work.