Medieval Hand Stitching and Finishing Techniques by Lady Sidney Eileen of Starkhafn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cora Ginsburg Llc Titi Halle Owner

CoraGinsburg-11/2006.qxd 11/22/06 11:26 AM Page 1 CORA GINSBURG LLC TITI HALLE OWNER A Catalogue of exquisite & rare works of art including 17th to 20th century costume textiles & needlework Winter 2006 by appointment 19 East 74th Street tel 212-744-1352 New York, NY 10021 fax 212-879-1601 www.coraginsburg.com [email protected] EMBROIDERED LINEN FOREHEAD CLOTH English, ca. 1610 Triangular in shape and lavishly embellished, a forehead cloth—also called a cross-cloth or crosset—was a feminine accessory sometimes worn with a coif, an informal type of cap. Rare after the mid-seventeenth century, forehead cloths first appeared in conjunction with the coif around 1580; embroidered with patterns to match, they were worn around the forehead and draped over the coif with the point facing backwards. Though the occasions on which a lady might wear a forehead cloth are not fully known, it seems that they were used for bedside receptions and in times of sickness. In his 1617 travels through Ireland, English author Fynes Moryson observed that, “Many weare such crosse-clothes or forehead clothes as our women use when they are sicke.” The remarkable embroidery seen here shows the practiced hand of a professional. Much fine needlework was accomplished domestically in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England, but there were also workshops and skilled individuals that catered to the luxury trade. The Broderers’ Company, an organization for professional needleworkers, was founded under Royal Charter in 1561; specialists were also retained for wealthy private households, and journeymen embroiderers were hired as necessity demanded. -

Winter Mitten Making

1 Winter Mitten Making By: Kielyn & Dave Marrone Version 2.0, October 2015 http://lureofthenorth.com 2 Note 1- This booklet is part of a series of DIY booklets published by Lure of the North. For all other publications in this series, please see our website at lureofthenorth.com. Published instructional booklets can be found under "Info Hub" in the main navigation menu. Note 2 – Lure Mitten Making Kits: These instructions are intended to be accompanied by our Mitten Making Kit, which is available through the “Store” section of our website at: http://lureofthenorth.com/shop. Of course, you can also gather all materials yourself and simply use these instructions as a guide, modifying to suit your requirements. Note 3 - Distribution: Feel free to distribute these instructions to anyone you please, with the requirement that this package be distributed in its entirety with no modifications whatsoever. These instructions are also not to be used for any commercial purpose. Thank you! Note 4 – Feedback and Further Help: Feedback is welcomed to improve clarity in future editions. For even more assistance you might consider taking a mitten making workshop with us. These workshops are run throughout Ontario, and include hands-on instructions and all materials. Go to lureofthenorth.com/calendar for an up to date schedule. Our Philosophy: This booklet describes our understanding of a traditional craft – these skills and this knowledge has traditionally been handed down from person to person and now we are attempting to do the same. We are happy to have the opportunity to share this knowledge with you, however, if you use these instructions and find them helpful, please give credit where it is due. -

Machine Embroidery Threads

Machine Embroidery Threads 17.110 Page 1 With all the threads available for machine embroidery, how do you know which one to choose? Consider the thread's size and fiber content as well as color, and for variety and fun, investigate specialty threads from metallic to glow-in-the-dark. Thread Sizes Rayon Rayon was developed as an alternative to Most natural silk. Rayon threads have the soft machine sheen of silk and are available in an embroidery incredible range of colors, usually in size 40 and sewing or 30. Because rayon is made from cellulose, threads are it accepts dyes readily for color brilliance; numbered unfortunately, it is also subject to fading from size with exposure to light or frequent 100 to 12, laundering. Choose rayon for projects with a where elegant appearance is the aim and larger number indicating a smaller thread gentle care is appropriate. Rayon thread is size. Sewing threads used for garment also a good choice for machine construction are usually size 50, while embroidered quilting motifs. embroidery designs are almost always digitized for size 40 thread. This means that Polyester the stitches in most embroidery designs are Polyester fibers are strong and durable. spaced so size 40 thread fills the design Their color range is similar to rayon threads, adequately without gaps or overlapping and they are easily substituted for rayon. threads. Colorfastness and durability make polyester When test-stitching reveals a design with an excellent choice for children's garments stitches so tightly packed it feels stiff, or other items that will be worn hard stitching with a finer size 50 or 60 thread is and/or washed often. -

23. Embroidery As an Embellishment in Fabric Decoration

EMBROIDERY AS AN EMBELLISHMENT IN FABRIC DECORATION By OLOWOOKERE PETER OLADIPO Department of Fine and Applied Arts, Federal College of Education, Osiele, Abeokuta. Abstract Nigeria is endowed with abundant human, natural and material resources, which could be used in different vocational practices. Practitioners have consistently practiced their art with attention to uniqueness and high quality forms, styles and content. Embroidery as a decorative process in Art has played principal roles in entrepreneurship development. Hence, this paper made a critical analysis of the forms, content and significant of embroidery in art, the thread colours, fabric motifs and pattern suitable for a successful embroidery design would also be considered. The general conclusion is that if embroidery is properly done, it would increase the embroiderers sense of creativity in our societal growth and the interested individual should be encourage to learn the craft so that the tradition will remain forever. Embroidery is an interesting stitching technique by which coloured threads, generally of silk or wool are used with a special needle to make a variety of stitches, and it is used to make an attractive design on garment, wall hanging or upholstery pieces. In Nigeria today, embroidery clothing are used far and wide and its unique feature and elegance remain the ability to trill and appeal to the people’s fervent love for it whereby the artisan considered different textile materials such as guinea brocade, damask and bringing out the significance of thread with which it is worked. Ojo (2000) defined, embroidery as an art of making pattern on textiles, leather, using threads of wool, linen, silk and needle. -

Glossary of Sewing Terms

Glossary of Sewing Terms Judith Christensen Professional Patternmaker ClothingPatterns101 Why Do You Need to Know Sewing Terms? There are quite a few sewing terms that you’ll need to know to be able to properly follow pattern instructions. If you’ve been sewing for a long time, you’ll probably know many of these terms – or at least, you know the technique, but might not know what it’s called. You’ll run across terms like “shirring”, “ease”, and “blousing”, and will need to be able to identify center front and the right side of the fabric. This brief glossary of sewing terms is designed to help you navigate your pattern, whether it’s one you purchased at a fabric store or downloaded from an online designer. You’ll find links within the glossary to “how-to” videos or more information at ClothingPatterns101.com Don’t worry – there’s no homework and no test! Just keep this glossary handy for reference when you need it! 2 A – Appliqué – A method of surface decoration made by cutting a decorative shape from fabric and stitching it to the surface of the piece being decorated. The stitching can be by hand (blanket stitch) or machine (zigzag or a decorative stitch). Armhole – The portion of the garment through which the arm extends, or a sleeve is sewn. Armholes come in many shapes and configurations, and can be an interesting part of a design. B - Backtack or backstitch – Stitches used at the beginning and end of a seam to secure the threads. To backstitch, stitch 2 or 3 stitches forward, then 2 or 3 stitches in reverse; then proceed to stitch the seam and repeat the backstitch at the end of the seam. -

General Information

General Information: Summer dresses, made from lightweight fabric like silk organza or printed cotton, were popular during the time of the early bustle era from 1869-1876 for excursions to the sea or sporting activities like tennis. Hence the name “seaside costume” comes. Beside strong and light colors also striped fabrics were popular. Striped fabric often was cut on the bias for ruches and decorations to create lovely patterns. At the beginning of the era skirts were supported by smaller crinolines with an additional bustle at the back. At the middle of the seventies the crinoline was displaced by the actual tournure or “Cul de Paris”. Information’s about the sewing pattern: A seam allowance of 5/8” (1,5cm) is included, except other directions directly on the sewing pattern. Transfer all marks carefully when cutting the fabric. Pleas always do a mockup first. To get the desired shape the dress should be worn over a corset and suitable underpinnings. The dress is intended to be worn for more sporting activities, so it is designed to be worn over a small to a medium size bustle pad. If you want to wear the dress over a small crinoline or a larger bustle you have to spread the back width of the skirt to the hip era. Plan to make two or three pleats into the skirt gore #2 and #3 at the hip section. The front waist piece and the front apron are cut as one piece, at the side and the back the apron pieces are sewn on and folded into regular pleats at the back. -

Multifunctional Blanket Stitch By: Magdamagda

Multifunctional Blanket Stitch By: magdamagda http://www.burdastyle.com/techniques/multifunctional-blanket-stitch What better time for hand sewing revelations than now when my sewing machine is in service? sigh I have been thinking about this for some time – one type of hand stitch that comes in handy in so many situations! I’ll point out the ones I thought about, new ideas are welcome! Known as the “blanket stitch” it can back up your sewing machine in some situations or even go where no sewing machine has gone before!!!! First this is how it’s done: I prefer to stitch right to left. Bring the thread to front at desired distance from the edge ( about 2 mm for buttonholes, 4-5 mm for serging). Take the thread over the edge of the cloth and pull the needle back to front through the same point. Make a loop around this thread segment at the cloth edge level. At some distance from the first “entry point” (3-4 mm for serging) and at the same distance from the edge thrust the needle from front to back and pull the needle through the loop formed by the remaining thread. You can help yourself by keeping the thread over the index finger of the left hand while doing so. Repeat, repeat, repeat..:) Tip: If you are serging, make sure not to pull the thread too much and cause the fabric to pluck. If you’re working on a button hole or doing some embroidery work pull the thread just right so that the thread remains straight: not too loose, not too tight:) Tip-tip:) : If the thread gets twisted on itself , you can straighten it out by sliding the needle close to the fabric and running the thread through your fingers from the fixed end towards the loose end (a few times) Note: Whatever you plan to use this stitch for, you’ll find it ideal when dealing with curved lines! A video to catch the basic move: Step 1 — [serging] Multifunctional Blanket Stitch 1 Use it for: 1) Serging (overcasting the raw edges of a fabric to prevent unraveling).. -

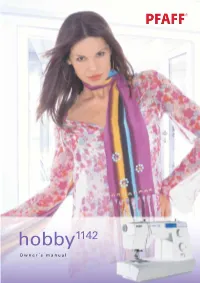

Hobby 1142-Manual-EN.Pdf

hobby114 2 Owner´s manual 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 28 8 9 27 211 2626 100 202 111 191 122 188 25 141 24 151 233 16 171 22 122 11 2020 133 Parts of your hobby™ 1142 sewing machine 1 Bobbin winder stop 2 Bobbin winder spindle 3 Hole for extra spool pin 4 Spool pin 5 Carrying handle 6 Bobbin thread guide 7 Take-up lever 8 Foot pressure dial 9 Face plate 10 Thread cutter 11 Buttonhole lever 12 Needle threader 13 Slide for lowering the feed dog 14 Needle plate 15 Accessory tray 16 Throat plate 17 Throat plate release button 18 Thumbscrew 19 Needle screw 20 Presser foot lifter 21 Thread tension dial 22 Reverse stitch lever 23 Power switch 24 Connecting socket 25 Stitch length dial 26 Stitch selector dial 27 Handwheel 28 Stitch width dial Congratulations on purchasing your new PFAFF® hobby! Your hobby is so easy to use and offers a whole range of features and accessories for you to explore. Please spend some time reading these operating instructions as it is a great way to learn the machine and also to make full use of the features. Your Pfaff dealer will be at your service with any help or advice you need. We wish you many enjoyable hours of sewing ! Some fabrics have excess dye which can cause discoloration on other fabric but also on your sewing machine. This discoloring may be very difÀ cult or impossible to remove. Fleece and denim fabric in especially red and blue often contain a lot of excess dye. -

Placket Construction Options

Placket Construction Options 1 Type1: Two Separate Bound Edges on a rectangular stitching box The key to this structure is that the bindings are initially stitched only to the seam allowances on each side, and NOT stitched across the end, of the clipped box, which means that they, and the clipped triangle at the bottom, remain loose and can be arranged before the nal nishing to go on either side of the fabric, as well as either over or under the other, after joining them at the sides. The widths and lengths of the bindings and the space between the sides of the clipped box determine all the other options available in this most exible of all the placket types I know of. Variation 1: Both bindings t inside the stitching box If you cut the bindings so the nished, folded widths of both are equal to or smaller than the space between the initial stitching lines, as shown above, you can arrange both ends at the clipped corners to all go on one side of the fabric (right or wrong side), along with the clipped triangle on the garment. You’ll get the best results if the underlapping binding is slightly smaller than the overlapping one. This can be man- aged by taking slightly deeper seam allowances when you join this piece, so they can initially be cut from the same strip. Or, you can place one end on each side with the Both ends on RS One end on RS, Both ends on WS triangle sandwiched in between. -

Elegant Table Runner H

Elegant Table Runner Designed By Patty Peterson Featuring Kreinik Metallic Machine Sewing Threads Finished size 11.5" X 40.75" ave you ever wondered how you can use the decorative stitches on H your sewing machine? Well here’s a quick and easy project where you can combine your machine’s decorative stitches with beautiful metallic threads and make an absolutely elegant table accessory. Whether you make it for your own home or as a gift, this table runner project will help you see the possibilities of those decorative machine stitches in a whole new light! ! SUPPLY LIST: 1.!!! Kreinik Metallic Machine Sewing Threads (34 colors available). This project uses:! Fine Twist threads: 0001 SILVER, 0002 PEWTER, 0003 WHITE GOLD, 0006 ANTIQUE DK GOLD 2.!!! Kreinik Silver Metallized Gimp:! 0030 SILVER, 0032 ANTIQUE GOLD, 0033 BRASSY GOLD! 3.!!! Size 14 Topstitch needle 4.!!! Sewing or embroidery machine/combination 5.!!! Walking foot or dual feed foot to construct table runner 6.!!! Tear-away stabilizer (depending on your hoop size) 7.!!! Bobbin thread 8.!!! Scissors 9.!!! Kreinik Custom Corder!™ 10. !If you plan on embroidering out the stitches in your embroidery hoop you will need 3/4 yard of Kona Bay, Black cotton fabric !! 11. If you are sewing the decorative stitches you will need!1/2 yard Kona Bay, Black cotton fabric 12.! Background fabric 13" x 44" (WOF) width of fabric (our model uses light weight patterned nylon)! 13.! Backing fabric: Kona Bay, Black cotton 13" X 44" (WOF) 14. !Extra fabric to sew test stitches, such as a couple of 6" x 6" squares 15. -

Stitches and Seam Techniques

Stitches and Seam Techniques Seen on Dark Age / Medieval Garments in Various Museum Collections The following notes have been gathered while attempting to learn stitches and construction techniques in use during the Dark Ages / Medieval period. The following is in no way a complete report, but only an indication of some techniques observed on extant Dark Ages / Medieval garments. Hopefully, others who are researching “actual” garments of the period in question will also report on their findings, so that comparisons can be made and a better total understanding achieved. Jennifer Baker –New Varangian Guard – Hodegon Branch – 2009 Contents VIKING AND SAXON STITCHES 1. RUNNING STITCH 2. OVERSEWING 3. HERRINGBONE 4. BLANKET STITCH SEAMS 1. SEAMS 2. BUTTED SEAMS 3. STAND-UP SEAM 4. SEAMS SPREAD OPEN AFTER JOIN IS MADE 5. “LAPPED” FELL SEAM 6. FELL SEAM WORKED ON WRONG SIDE OF GARMENT FINISHES ON RAW EDGES OF SEAMS SEWING ON TABLET WOVEN BRAID HEMS OTHER STITCHES FOUND IN ARCHEOLOGICAL FINDS REFERENCES 1 Stitches and Seam Techniques VIKING AND SAXON STITCHES There are only four basic stitches to master: 1. RUNNING STITCH , 2. OVERSEWING, ALSO KNOWN AS OVERCAST STITCH OR WHIP STITCH 3. HERRINGBONE , ALSO KNOWN AS CATCH STITCH 4. AND BLANKET STITCH. ALSO KNOWN AS BUTTONHOLE STITCH Running stitch is probably the easiest to start with followed by oversewing. With these two stitches you can make clothing. The other two are for decorative edging. These directions are for a right handed person, if you are left handed remember to reverse all directions. 2 Stitches and Seam Techniques RUNNING STITCH A running stitch is done through one or more layers of fabric (but normally two or more), with the needle going down and up, down and up, in an essentially straight line. -

Powerhouse Museum Lace Collection: Glossary of Terms Used in the Documentation – Blue Files and Collection Notebooks

Book Appendix Glossary 12-02 Powerhouse Museum Lace Collection: Glossary of terms used in the documentation – Blue files and collection notebooks. Rosemary Shepherd: 1983 to 2003 The following references were used in the documentation. For needle laces: Therese de Dillmont, The Complete Encyclopaedia of Needlework, Running Press reprint, Philadelphia, 1971 For bobbin laces: Bridget M Cook and Geraldine Stott, The Book of Bobbin Lace Stitches, A H & A W Reed, Sydney, 1980 The principal historical reference: Santina Levey, Lace a History, Victoria and Albert Museum and W H Maney, Leeds, 1983 In compiling the glossary reference was also made to Alexandra Stillwell’s Illustrated dictionary of lacemaking, Cassell, London 1996 General lace and lacemaking terms A border, flounce or edging is a length of lace with one shaped edge (headside) and one straight edge (footside). The headside shaping may be as insignificant as a straight or undulating line of picots, or as pronounced as deep ‘van Dyke’ scallops. ‘Border’ is used for laces to 100mm and ‘flounce’ for laces wider than 100 mm and these are the terms used in the documentation of the Powerhouse collection. The term ‘lace edging’ is often used elsewhere instead of border, for very narrow laces. An insertion is usually a length of lace with two straight edges (footsides) which are stitched directly onto the mounting fabric, the fabric then being cut away behind the lace. Ocasionally lace insertions are shaped (for example, square or triangular motifs for use on household linen) in which case they are entirely enclosed by a footside. See also ‘panel’ and ‘engrelure’ A lace panel is usually has finished edges, enclosing a specially designed motif.