Global-GMG Merger Inquiry: Appendices and Glossary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EMBARGOED 00.01 2 February 2012 REGIONAL

PRESS RELEASE – EMBARGOED 00.01 2 February 2012 Year-on-Year growth for Smooth Radio UK and Real Radio brand Almost 5.6 million adults tune into a GMG Radio station each week – an extra 376,000 (YonY) Smooth Radio’s digital audience approaches 1 million adults each week GMG Radio’s Smooth Radio and Real Radio brands have recorded impressive year-on- year growth, according to the latest audience research out today (Thursday). 5.6 million adults now tune into one of the group’s stations each week - 376,000 more than a year ago. Smooth Radio UK’s weekly reach now stands at over 3.3 million adult listeners a week, up 231,000 on the same time last year. The audience also likes what they hear, with total hours listened to the station now standing at 25.75 million - almost two million (1.88m) more than a year ago – making it the UK’s second most listened to national commercial radio station. Simon Bates at Breakfast is celebrating his first year on Smooth Radio and has grown the breakfast audience by 69,000 to almost 1.4 million a week (YoY). For the group’s Real Radio brand the audience growth trend is also upwards. The stations, which broadcast on FM in Wales, Scotland, the North East and North West of England and Yorkshire and digitally across the UK, have added a total of 164,000 new adult listeners in the last year to give them a new weekly reach of just over 2.5 million adults. -

Aid to Channel 4 Linked to Digital Switchover Invitation to Submit Comments Pursuant to Article 88(2) of the EC Treaty

C 137/16EN Official Journal of the European Union 4.6.2008 STATE AID — UNITED KINGDOM State aid C 13/08 (ex N 589/07) — Aid to Channel 4 linked to digital switchover Invitation to submit comments pursuant to Article 88(2) of the EC Treaty (Text with EEA relevance) (2008/C 137/10) By means of the letter dated 2 April 2008 reproduced in the authentic language on the pages following this summary, the Commission notified the United Kingdom of its decision to initiate the procedure laid down in Article 88(2) of the EC Treaty concerning the proposed financial support to Channel 4 to enable it to meet the costs of digital switchover. Interested parties may submit their comments on the measure in respect of which the Commission is initi- ating the procedure within one month of the date of publication of this summary and the following letter, to: European Commission Directorate-General for Competition State Aid Registry SPA 3 6/5 B-1049 Brussels Fax (32-2) 296 12 42 These comments will be communicated to the United Kingdom. Confidential treatment of the identity of the interested party submitting the comments may be requested in writing, stating the reasons for the request. TEXT OF SUMMARY The UK authorities accept that the notified measure constitutes an aid within the meaning of Article 87(1) of the Treaty. They argue however that the measure is compatible with the Treaty by virtue of Article 86(2), having regard to the Commission's 1 PROCEDURE Communication ( ) on the application of the State aid rules in relation to public service broadcasting (‘the Communication’) and the three particular criteria according to which the compati- The measures on which the Commission has opened the proce- bility of aid of this nature falls to be judged, namely, definition, dure laid down in Article 88(2) was brought to the Commis- entrustment and proportionality. -

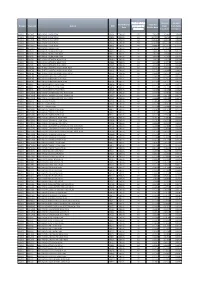

Domain Stationid Station UDC Performance Date

Number of days Amount Amount Performance Total Per Domain StationId Station UDC processed for from from Public Date Minute Rate distribution Broadcast Reception RADIO BR ONE BBC RADIO 1 NON PEAK BRA01 CENSUS 92 7.8347 4.2881 3.5466 RADIO BR ONE BBC RADIO 1 LOW PEAK BRB01 CENSUS 92 10.7078 7.1612 3.5466 RADIO BR ONE BBC RADIO 1 HIGH PEAK BRC01 CENSUS 92 13.5380 9.9913 3.5466 RADIO BR TWO BBC RADIO 2 NON PEAK BRA02 CENSUS 92 17.4596 11.2373 6.2223 RADIO BR TWO BBC RADIO 2 LOW PEAK BRB02 CENSUS 92 24.9887 18.7663 6.2223 RADIO BR TWO BBC RADIO 2 HIGH PEAK BRC02 CENSUS 92 32.4053 26.1830 6.2223 RADIO BR1EXT BBC RADIO 1XTRA NON PEAK BRA10 CENSUS 92 1.4814 1.4075 0.0739 RADIO BR1EXT BBC RADIO 1XTRA LOW PEAK BRB10 CENSUS 92 2.4245 2.3506 0.0739 RADIO BR1EXT BBC RADIO 1XTRA HIGH PEAK BRC10 CENSUS 92 3.3534 3.2795 0.0739 RADIO BRASIA BBC ASIAN NETWORK NON PEAK BRA65 CENSUS 92 1.4691 1.4593 0.0098 RADIO BRASIA BBC ASIAN NETWORK LOW PEAK BRB65 CENSUS 92 2.4468 2.4371 0.0098 RADIO BRASIA BBC ASIAN NETWORK HIGH PEAK BRC65 CENSUS 92 3.4100 3.4003 0.0098 RADIO BRBEDS BBC THREE COUNTIES RADIO NON PEAK BRA62 CENSUS 92 0.1516 0.1104 0.0411 RADIO BRBEDS BBC THREE COUNTIES RADIO LOW PEAK BRB62 CENSUS 92 0.2256 0.1844 0.0411 RADIO BRBEDS BBC THREE COUNTIES RADIO HIGH PEAK BRC62 CENSUS 92 0.2985 0.2573 0.0411 RADIO BRBERK BBC RADIO BERKSHIRE NON PEAK BRA64 CENSUS 92 0.0803 0.0569 0.0233 RADIO BRBERK BBC RADIO BERKSHIRE LOW PEAK BRB64 CENSUS 92 0.1184 0.0951 0.0233 RADIO BRBERK BBC RADIO BERKSHIRE HIGH PEAK BRC64 CENSUS 92 0.1560 0.1327 0.0233 RADIO BRBRIS BBC -

The BBC's Use of Spectrum

The BBC’s Efficient and Effective use of Spectrum Review by Deloitte & Touche LLP commissioned by the BBC Trust’s Finance and Strategy Committee BBC’s Trust Response to the Deloitte & Touche LLPValue for Money study It is the responsibility of the BBC Trust,under the As the report acknowledges the BBC’s focus since Royal Charter,to ensure that Value for Money is the launch of Freeview on maximising the reach achieved by the BBC through its spending of the of the service, the robustness of the signal and licence fee. the picture quality has supported the development In order to fulfil this responsibility,the Trust and success of the digital terrestrial television commissions and publishes a series of independent (DTT) platform. Freeview is now established as the Value for Money reviews each year after discussing most popular digital TV platform. its programme with the Comptroller and Auditor This has led to increased demand for capacity General – the head of the National Audit Office as the BBC and other broadcasters develop (NAO).The reviews are undertaken by the NAO aspirations for new services such as high definition or other external agencies. television. Since capacity on the platform is finite, This study,commissioned by the Trust’s Finance the opportunity costs of spectrum use are high. and Strategy Committee on behalf of the Trust and The BBC must now change its focus from building undertaken by Deloitte & Touche LLP (“Deloitte”), the DTT platform to ensuring that it uses its looks at how efficiently and effectively the BBC spectrum capacity as efficiently as possible and uses the spectrum available to it, and provides provides maximum Value for Money to licence insight into the future challenges and opportunities payers.The BBC Executive affirms this position facing the BBC in the use of the spectrum. -

GMG Radio Response to the Ofcom Consultation on Review of Procedures for Handling Broadcasting Complaints, Investigations and Sanctions

GMG Radio response to the Ofcom consultation on review of procedures for handling broadcasting complaints, investigations and sanctions Introduction GMG Radio plc is part of The Guardian Media Group and operates fourteen analogue licences within the UK under the separate Real, Smooth and Rock Radio brands. The company was an inaugural partner and is currently a 35% shareholder in the MXR regional multiplex consortium as well as being a long-term service provider on each of its platforms. GMG Radio is also a founding partner and stakeholder in Digital Radio UK, the body charged with helping prepare the UK for digital switchover. GMG Radio considers regulatory compliance to be a hugely important and crucial element to our overall business operation and welcomes proposals which are genuinely designed to assist in improving standards and enhance understanding of regulatory procedures. We note this consultation seeks stakeholder views on proposed changes to procedures as opposed to responses to specific questions. Current understanding Ofcom has no wish to dilute the current process by which it can diligently follow when investigating breaches of broadcast licences, investigating complaints including those on fairness and privacy issues and the consideration of statutory sanctions for proven breaches. As such this consultation is specifically placed within the public arena in order to enlist stakeholder opinions on planned changes which are ultimately designed to ensure an ongoing commitment to the principles of continued fairness to those directly involved and at the same time introduce new procedures which are clearer, simpler and can be implemented as effectively and efficiently as possible. The consultation documents sets out proposals for new procedures covering the handling of broadcasting complaints, investigations and sanctions and it invites written views and comments on each of them prior to the publishing of a finalized version. -

3 Radio and Audio Content 3 3.1 Recent Developments in Scotland

3 Radio and audio content 3 3.1 Recent developments in Scotland Real Radio Scotland has been rebranded as Heart In February 2014 Capital Scotland was sold to the Irish media holding company, Communicorp. It was sold as part of eight stations divested by Global Radio to satisfy the UK regulatory authorities following the acquisition, two years ago, of GMG Radio from Guardian Media Group. Under a brand licensing agreement, Communicorp has rebranded the 'Real' stations under the 'Heart' franchise and plans to relaunch the 'Smooth' stations following the reintroduction of local programming. Therefore, Real Radio Scotland was rebranded as Heart Scotland in May 2014. XFM Scotland was re-launched by its owners, Global Radio, in March 2014. 3.2 Radio station availability Five new community radio stations are available to listeners in Scotland Scotland’s community radio industry has continued to grow. There are now 23 community stations on air, out of the 31 licences that have been awarded in Scotland. New to air in 2013/14 were East Coast FM, Irvine Beat FM, Crystal Radio, and K107 FM. Irvine Beat FM has received funding from the Lottery Awards for All fund to build a training studio. Nevis Radio, which serves Fort William and the surrounding areas, was originally licensed as a commercial radio service, but having chosen to become a community radio service it was awarded this licence instead, on application. The remaining eight of the most recent round of licence awards are preparing to launch. A licensee has two years from the date of the licence award in which to launch a service. -

Pocketbook for You, in Any Print Style: Including Updated and Filtered Data, However You Want It

Hello Since 1994, Media UK - www.mediauk.com - has contained a full media directory. We now contain media news from over 50 sources, RAJAR and playlist information, the industry's widest selection of radio jobs, and much more - and it's all free. From our directory, we're proud to be able to produce a new edition of the Radio Pocket Book. We've based this on the Radio Authority version that was available when we launched 17 years ago. We hope you find it useful. Enjoy this return of an old favourite: and set mediauk.com on your browser favourites list. James Cridland Managing Director Media UK First published in Great Britain in September 2011 Copyright © 1994-2011 Not At All Bad Ltd. All Rights Reserved. mediauk.com/terms This edition produced October 18, 2011 Set in Book Antiqua Printed on dead trees Published by Not At All Bad Ltd (t/a Media UK) Registered in England, No 6312072 Registered Office (not for correspondence): 96a Curtain Road, London EC2A 3AA 020 7100 1811 [email protected] @mediauk www.mediauk.com Foreword In 1975, when I was 13, I wrote to the IBA to ask for a copy of their latest publication grandly titled Transmitting stations: a Pocket Guide. The year before I had listened with excitement to the launch of our local commercial station, Liverpool's Radio City, and wanted to find out what other stations I might be able to pick up. In those days the Guide covered TV as well as radio, which could only manage to fill two pages – but then there were only 19 “ILR” stations. -

BBC Radio Scotland’S Delivery of the BBC’S Public Purposes

BBC Nations Radio Review BBC Nations Radio Review Quantitative audience research assessing BBC Radio Scotland’s delivery of the BBC’s Public Purposes Prepared for September 20 2011 Prepared by Kantar Media: Trevor Vagg, Sara Reid and Julia Harrison. Ref: 45110564. © Kantar Media. Contact: 020 7656 5500 All rights reserved www.kantarmedia.com www.kantarmedia.com reserved P a g e | 2 Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Objectives.................................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Methodology ............................................................................................................................... 3 1.3 Explanation of Public Purposes and performance gaps.............................................................. 4 2. Executive summary ......................................................................................................................... 6 3. Overall performance measures for BBC Radio Scotland............................................................... 10 3.1 Overall impression of BBC Radio Scotland ................................................................................ 10 3.2 Likelihood to miss BBC Radio Scotland ..................................................................................... 12 3.3 Perceived value for money of BBC Radio Scotland .................................................................. -

Capital Birmingham Should Not Be Allowed to Make the Changes to The

Spence, Mr Consultation question: Should regional radio station Capital FM (Birmingham) be permitted to make the changes to its Character of Service as proposed with particular regard to the statutory criteria as set out in the summary? (The Broadcasting Act 1990 Section 106 (1A) (b) and (d) relating to Format changes). Capital Birmingham should not be allowed to make the changes to the Character of Service as this would essentially change the station from am urban/black music station to a hit music station format which can potentially stop playing urban music if they wanted to if in the future it becomes less mainstream. The format change represents a real danger to the radio landscape in Birmingham as it can so significantly reduce the choice of music available in the area over time. It will make the station sound too similar to it's main competitors in the area on FM. I am not happy with the decision in particular to remove the commitment to listeners of African or Afro-Caribbean origin in terms of content and music. I do not believe the music output of Capital Birmingham should be allowed to be aligned to that of Yorkshire or London without a readvertisement of the license as the change requested is far too significant. I believe that the format must retain the words 'URBAN CONTEMPORARY BLACK MUSIC' and 'REGGAE, RnB AND HIP HOP' in order to be an acceptable request. The new requested format is already provided in much better quality by BBC Radio 1. I am not happy with the way the station has been allowed to gradually change from Choice FM in the mid 90s to the present day Capital FM with such a dramatic change in music output despite only slight changes to the official OFCOM agreed station format, while Choice London and Capital FM co-exist in London providing 2 very different sounding services. -

Broadcast Bulletin Issue Number 219 03/12/12

Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin Issue number 219 3 December 2012 1 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 219 3 December 2012 Contents Introduction 3 Notice of Sanction Sister Ruby Ramadan Special Radio Asian Fever (Leeds), 17 August 2011, 12:00 and 18 August 2011, 11:00 4 Standards cases In Breach Asian Sound Radio Asian Sound Radio, 9 April 2012, 11:30 to 12:30 6 American Dad FX, 11 August 2012, 20:30 14 GirlGirl ChatGirl TV (Sky Channel 937), 22 August 2012, 07:30 to 08:30 18 Big Wednesday with Shawn Phonic FM, 12 September 2012, 11:40 22 Borkotmoy Sehri NTV, 30 July 2012, 02:00 25 Advertising scheduling cases In Breach Advertising minutage and advertising break patterns Sahara One, 16 July 2012 to 31 July 2012, various times 28 Advertising minutage Vox Africa, 1 June 2012 to 5 July 2012, various times 30 Other Programmes Not in Breach 32 Complaints Assessed, Not Investigated 33 Investigations List 42 2 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 219 3 December 2012 Introduction Under the Communications Act 2003, Ofcom has a duty to set standards for broadcast content as appear to it best calculated to secure the standards objectives1, Ofcom must include these standards in a code or codes. These are listed below. The Broadcast Bulletin reports on the outcome of investigations into alleged breaches of those Ofcom codes, as well as licence conditions with which broadcasters regulated by Ofcom are required to comply. These include: a) Ofcom’s Broadcasting Code (“the Code”), which, can be found at: http://stakeholders.ofcom.org.uk/broadcasting/broadcast-codes/broadcast-code/. -

The Evolution of British Asian Radio in England: 1960 – 2004

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bournemouth University Research Online The Evolution of British Asian Radio in England: 1960 – 2004 Gloria Khamkar Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of Bournemouth University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2016 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and due acknowledgement must always be made of the use of any material contained in, or derived from, this thesis. II ABSTRACT Title: The Evolution of British Asian Radio in England: 1960 – 2004 Author: Gloria Khamkar This doctoral research examines the evolution of British Asian radio in England from 1960 to 2004. During the post-war period an Asian community started migrating to Britain to seek employment as a result of the industrial labour shortage. The BBC and the independent local radio sector tried to cater to this newly arrived migrant community through its radio output either in their mother tongue or in the English language. Later, this Asian community started its own separate radio services. This research project explores this transformation of Asian radio, from broadcasting radio programmes for the Asian community on existing radio stations, to the creation of independent local and community radio stations, catering to the Asian community exclusively in England. Existing research concentrates on the stereotype images and lack of representation of Asian community on the British radio; it lacks a comprehensive overview of the role of radio during the settlement period of the newly migrant Asian community. -

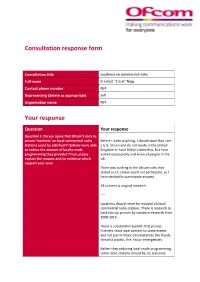

Localness on Commercial Radio Full Name Erzsebet “Erzsie” Nagy Contact Phone Number N/A Representing (Delete As Appropriate) Self Organisation Name N/A

Consultation response form Consultation title Localness on commercial radio Full name Erzsebet “Erzsie” Nagy Contact phone number N/A Representing (delete as appropriate) Self Organisation name N/A Your response Question Your response Question 1: Do you agree that Ofcom’s duty to secure ‘localness’ on local commercial radio Before I write anything, I should state that I am stations could be satisfied if stations were able a U.S. citizen and do not reside in the United to reduce the amount of locally-made Kingdom or have British citizenship, but have programming they provide? If not, please visited occasionally and know of people in the explain the reasons and/or evidence which UK. support your view. There was nothing in the Ofcom rules that stated a U.S. citizen could not participate, so I have decided to participate anyway. All content is original research. ---- Localness should never be reduced on local commercial radio stations. There is research to back this up, proven by statistical research from 2008-2014. There is substantial research that proves listeners value local content to some extent, and not just in major circumstances like floods, terrorist attacks, fire, major emergencies. Rather than reducing local-made programming, some radio stations should be, by statutory requirement, have as much local programming and content as necessary. There is substantial evidence from American researchers – 2004, 2008, 2012, 2014 that proved listeners value locality as a major selling point. Unofficial research in 2007 has proved this. No station should be local for only 3 hours a day, whatever the day of week.