Media and Nation Building in Twentieth-Century India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GIPE-012270-Contents.Pdf

SELECTIONS FROM OFFICIAL LETTERS AND DOCUMENTS RELATING TO THE UfE OF RAJA RAMMOHUN ROY VOL. I EDITED BY lW BAHADUR RAMAPRASAD CHANDA, F.R.A.S.B. L.u Supmnteml.nt of lhe ArchteO!ogit:..S Section. lnd;.n MMe~~m, CUct<lt.t. AND )ATINDRA KUMAR MAJUMDAR, M.A., Ph.D. (LoNDON), Of the Middk Temple, 11uris~er-M-Ltw, ddfJOcote, High Court, C41Cflll4 Sometime Professor of Pb.Josophy. Presidency College, C..Scutt.t. With an Introductory Memoir CALCUTIA ORIENTAL BOOK AGENCY 9> PANCHANAN GHOSE LANE, CALCUTTA Published in 1938 Printed and Published by J. C. Sarkhel, at the Calcutta Oriental Press Ltd., 9, Pancb&nan Ghose Lane, Calcutta. r---~-----~-,- 1 I I I I I l --- ---·~-- ---' -- ____j [By courtesy of Rammohun Centenary Committee] PREFACE By his refor~J~ing activities Raja Rammohun Roy made many enemies among the orthodox Hindus as well as orthodox Christians. Some of his orthodox countrymen, not satis· fied with meeting his arguments with arguments, went to the length of spreading calumnies against him regarding his cha· racter and integrity. These calumnies found their way into the works of som~ of his Indian biographers. Miss S, D. Collet has, however, very ably defended the charact~ of the Raja against these calumniet! in her work, "The Life and Letters of Raja Rammohun Roy." But recently documents in the archives of the Governments of Bengal and India as well as of the Calcutta High Court were laid under contribution to support some of these calumnies. These activities reached their climax when on the eve of the centenary celebration of the death of Raja Rammohun Roy on the 27th September, 1933, short extracts were published from the Bill of Complaint of a auit brought against him in the Supreme Court by his nephew Govindaprasad Roy to prove his alleged iniquities. -

Special Bulletin Remembering Mahatma Gandhi

Special Bulletin Remembering Mahatma Gandhi Dear Members and Well Wishers Let me convey, on behalf of the Council of the Asiatic Society, our greetings and good wishes to everybody on the eve of the ensuing festivals in different parts of the country. I take this opportunity to share with you the fact that as per the existing convention Ordinary Monthly Meeting of the members is not held for two months, namely October and November. Eventually, the Monthly Bulletin of the Society is also not published and circulated. But this year being the beginning of 150 years of Birth Anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi, the whole nation is up on its toes to celebrate the occasion in the most befitting manner. The Government of India has taken major initiatives to commemorate this eventful moment through its different ministries. As a consequence, the Ministry of Culture, Govt. of India, has followed it up with directives to various departments and institutions-attached, subordinate, all autonomous bodies including the Asiatic Society, under its control for taking up numerous academic programmes. The Asiatic Society being the oldest premier institution of learning in whole of this continent, which has already been declared as an Institution of National Importance since 1984 by an Act of the Parliament, Govt. of India, has committed itself to organise a number of programmes throughout the year. These programmes Include (i) holding of a National Seminar with leading academicians who have been engaged in the cultivation broadly on the life and activities (including the basic philosophical tenets) of Mahatma Gandhi, (ii) reprinting of a book entitled Studies in Gandhism (1940) written and published by late Professor Nirmal Kumar Bose (1901-1972), and (iii) organizing a series of monthly lectures for coming one year. -

Gandhi Wields the Weapon of Moral Power (Three Case Stories)

Gandhi wields the weapon of moral power (Three Case Stories) By Gene Sharp Foreword by: Dr. Albert Einstein First Published: September 1960 Printed & Published by: Navajivan Publishing House Ahmedabad 380 014 (INDIA) Phone: 079 – 27540635 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.navajivantrust.org Gandhi wields the weapon of moral power FOREWORD By Dr. Albert Einstein This book reports facts and nothing but facts — facts which have all been published before. And yet it is a truly- important work destined to have a great educational effect. It is a history of India's peaceful- struggle for liberation under Gandhi's guidance. All that happened there came about in our time — under our very eyes. What makes the book into a most effective work of art is simply the choice and arrangement of the facts reported. It is the skill pf the born historian, in whose hands the various threads are held together and woven into a pattern from which a complete picture emerges. How is it that a young man is able to create such a mature work? The author gives us the explanation in an introduction: He considers it his bounden duty to serve a cause with all his ower and without flinching from any sacrifice, a cause v aich was clearly embodied in Gandhi's unique personality: to overcome, by means of the awakening of moral forces, the danger of self-destruction by which humanity is threatened through breath-taking technical developments. The threatening downfall is characterized by such terms as "depersonalization" regimentation “total war"; salvation by the words “personal responsibility together with non-violence and service to mankind in the spirit of Gandhi I believe the author to be perfectly right in his claim that each individual must come to a clear decision for himself in this important matter: There is no “middle ground ". -

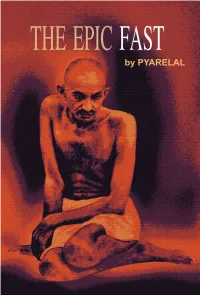

The Epic Fast

The Epic Fast The Epic Fast By : Pyarelal First Published: 1932 Printed & Published by: Navajivan Publishing House Ahmedabad 380 014 (INDIA) Phone: 079 – 27540635 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.navajivantrust.org www.mkgandhi.org Page 1 The Epic Fast To The Down-Trodden of the World www.mkgandhi.org Page 2 The Epic Fast PUBLISHER'S NOTE This book was first published in 1932 i.e. immediately after Yeravda Pact. Reader may get glimpses of that period from the Preface of the first edition by Pyarelal Nayar and from the Foreward by C. Rajagopalachari. Due to the debate regarding constitutional provisions about reservation after six decades of independence students of Gandhian Thought have been searching the book which has been out of print since long. A publisher in Tamilnadu has asked for permission to translate the book in Tamil and for its publication. We welcomed the proposal and agreed to publish the Tamil version. Obviously the original book in English too will be in demand on publication of the Tamil version. Hence this reprint. We are sure, this publication will help our readers as a beacon light to reach out to the inner reaches of their conscience to find the right path in this world of conflicting claims. In this context, Gandhiji's The Epic Fast has no parallel. 16-07-07 www.mkgandhi.org Page 3 The Epic Fast PREFACE OF THE FIRST EDITION IT was my good fortune during Gandhiji's recent fast to be in constant attendance on him with Sjt. Brijkishen of Delhi, a fellow worker in the cause. -

A Hermeneutic Study of Bengali Modernism

Modern Intellectual History http://journals.cambridge.org/MIH Additional services for Modern Intellectual History: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here FROM IMPERIAL TO INTERNATIONAL HORIZONS: A HERMENEUTIC STUDY OF BENGALI MODERNISM KRIS MANJAPRA Modern Intellectual History / Volume 8 / Issue 02 / August 2011, pp 327 359 DOI: 10.1017/S1479244311000217, Published online: 28 July 2011 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S1479244311000217 How to cite this article: KRIS MANJAPRA (2011). FROM IMPERIAL TO INTERNATIONAL HORIZONS: A HERMENEUTIC STUDY OF BENGALI MODERNISM. Modern Intellectual History, 8, pp 327359 doi:10.1017/S1479244311000217 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/MIH, IP address: 130.64.2.235 on 25 Oct 2012 Modern Intellectual History, 8, 2 (2011), pp. 327–359 C Cambridge University Press 2011 doi:10.1017/S1479244311000217 from imperial to international horizons: a hermeneutic study of bengali modernism∗ kris manjapra Department of History, Tufts University Email: [email protected] This essay provides a close study of the international horizons of Kallol, a Bengali literary journal, published in post-World War I Calcutta. It uncovers a historical pattern of Bengali intellectual life that marked the period from the 1870stothe1920s, whereby an imperial imagination was transformed into an international one, as a generation of intellectuals born between 1885 and 1905 reinvented the political category of “youth”. Hermeneutics, as a philosophically informed study of how meaning is created through conversation, and grounded in this essay in the thought of Hans Georg Gadamer, helps to reveal this pattern. -

Nandan Gupta. `Prak-Bibar` Parbe Samaresh Basu. Nimai Bandyopadhyay

BOOK DESCRIPTION AUTHOR " Contemporary India ". Nandan Gupta. `Prak-Bibar` Parbe Samaresh Basu. Nimai Bandyopadhyay. 100 Great Lives. John Cannong. 100 Most important Indians Today. Sterling Special. 100 Most Important Indians Today. Sterling Special. 1787 The Grand Convention. Clinton Rossiter. 1952 Act of Provident Fund as Amended on 16th November 1995. Government of India. 1993 Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action. Indian Institute of Human Rights. 19e May ebong Assame Bangaliar Ostiter Sonkot. Bijit kumar Bhattacharjee. 19-er Basha Sohidera. Dilip kanti Laskar. 20 Tales From Shakespeare. Charles & Mary Lamb. 25 ways to Motivate People. Steve Chandler and Scott Richardson. 42-er Bharat Chara Andolane Srihatta-Cacharer abodan. Debashish Roy. 71 Judhe Pakisthan, Bharat O Bangaladesh. Deb Dullal Bangopadhyay. A Book of Education for Beginners. Bhatia and Bhatia. A River Sutra. Gita Mehta. A study of the philosophy of vivekananda. Tapash Shankar Dutta. A advaita concept of falsity-a critical study. Nirod Baron Chakravarty. A B C of Human Rights. Indian Institute of Human Rights. A Basic Grammar Of Moden Hindi. ----- A Book of English Essays. W E Williams. A Book of English Prose and Poetry. Macmillan India Ltd.. A book of English prose and poetry. Dutta & Bhattacharjee. A brief introduction to psychology. Clifford T Morgan. A bureaucrat`s diary. Prakash Krishen. A century of government and politics in North East India. V V Rao and Niru Hazarika. A Companion To Ethics. Peter Singer. A Companion to Indian Fiction in E nglish. Pier Paolo Piciucco. A Comparative Approach to American History. C Vann Woodward. A comparative study of Religion : A sufi and a Sanatani ( Ramakrishana). -

Sita Devi-Shanta Devi and Women's Educational Development in 20 Century Bengal

Volume : 1 | Issue : 1 | January 2012 ISSN : 2250 - 1991 Research Paper Education Sita Devi-Shanta Devi and Women's Educational Development in 20th Century Bengal * Prarthita Biswas * Asst. Prof., Pailan College of Education, Joka, Kolkata ABSTRACT This synopsis tries to investigate the cultural as well as educational development of women of the 20th Century Bengali society which has been observed in the writing writings of Shanta Devi and Sita Devi concerning women and to examine in details about the women's literary works during that time. It would be fruitful to historically review the short stories as well as the novels of both Shanta Devi and Sita Devi to get a critical understanding about the various spheres they touched many of which are still being debated till date. The study may not be able to settle the debates going on for centuries about women emancipation and specially about women's educational development in 20th Century Bengal but will sincerely attempt to help scholars think in a more practical and objective manner . Keywords : Women's Education, Emancipation, Literary Works, Women's Enlightenment Introduction 1917, Sita Devi's first original short story Light of the Eyes appeared in Prabasi, her sister's first one Sunanda appearing he two sisters, Sita Devi and Shanta Devi from whose in the same magazine a month later. work a selection is translated and offered to the In 1918, they wrote in collaboration a novel, “Udyanlata” (The TEnglish-reading public are daughters of Sri Garden Creeper in English) , a serial for Prabasi. This was Ramananda Chatterjee, a well-known personality and who given over a column in the Times Literary Supplement, from the launched “Prabasi Patrika” in the year 1901. -

Indian Statistical Institute Alumni Association (Isiaa)

INDIAN STATISTICAL INSTITUTE ALUMNI ASSOCIATION (ISIAA) Provisional Voter List (2015-2017) First and Middle SL.# Last Name E-mail Address Address Names 2 Ratan Kumar Ghosh [email protected] C/O Kajal Mukherjee, Flat No.204,8, Sultan Alam Road, Kolkata-700 033 4 Gour Mohan Chatterji Prof. & HOD, MBA Department , Galgotias Business School, 1, 8 Satyendra Nath Chakraborty [email protected] Knowledge Park - I, Greater Noida - 201306 10 Vinod Karan Sethi Institute of Social Sciences, University of Agra, U.P. 282 004 15 Biswatosh Sengupta [email protected] P35/A Motijheel Avenue, Kolkata 700 074 16 D.P Roychowdhury 18 Sanjit Kumar Banerjee B 5/3 Karunamoyee Housing Estate, Salt Lake, Kolkata 700 091 19 Baldev Raj Panesar Y.M.C.A., Wellington Branch, 42 S.N. Banerjee Road, Kolkata 700 014 20 Salil Kumar Chaudhuri [email protected] 42/6 Nabin Chandra Das Road, Kolkata 700 090 21 Manoj Kanti Ghosh A/9 Uttarayan Sarani, Nowdapara (North), Ariadaha, Kolkata 700 057 22 M.T. Jacob Joint Director, C.S.O., 1, Council House Street, Kolkata 700 001 Department of Mathematics, University of Western Australia Nedlando, 23 K. Vijayan [email protected] WEST AUSTRALIA 6009 [email protected], Flat No. 303, V. V. Vintage Residency, 6-3-1093 Rajbhavan Road, 24 V. Nagi Reddy [email protected] Somajiguda, Hyderabad 500082 National Institute of Biomedical Genomics, Netaji Subhas Sanatorium 25 Partha Pratim Majumder [email protected] (T.B. Hospital), 2nd Floor P.O.: N.S.S., Kalyani 741251 26 Amita Majumder [email protected] E.R.U., Indian Statistical Institute, 203, B.T. -

Mary Lago Collection Scope and Content Note

Special Collections 401 Ellis Library Columbia, MO 65201 (573) 882-0076 & Rare Books [email protected] University of Missouri Libraries http://library.missouri.edu/specialcollections/ Mary Lago Collection Scope and Content Note The massive correspondence of E. M. Forster, which Professor Lago gathered from archives all over the world, is one of the prominent features of the collection, with over 15,000 letters. It was assembled in preparation for an edition of selected letters that she edited in collaboration with P. N. Furbank, Forster’s authorized biographer. A similar archive of Forster letters has been deposited in King’s College. The collection also includes copies of the correspondence of William Rothenstein, Edward John Thompson, Max Beerbohm, Rabindranath Tagore, Edward Burne-Jones, D.S. MacColl, Christiana Herringham, and Arthur Henry Fox-Strangways. These materials were also gathered by her in preparation for subsequent books. In addition, the collection contains Lago’s extensive personal and professional correspondence, including correspondence with Buddhadeva Bose, Penelope Fitzgerald, P.N. Furbank, Dilys Hamlett, Krishna Kripalani, Celia Rooke, Stella Rhys, Satyajit Ray, Amitendranath Tagore, E.P. Thompson, Lance Thirkell, Pratima Tagore, John Rothenstein and his family, Eric and Nancy Crozier, Michael Holroyd, Margaret Drabble, Santha Rama Rau, Hsiao Ch’ien, Ted Uppmann, Edith Weiss-Mann, Arthur Mendel, Zia Moyheddin and numerous others. The collection is supplemented by extensive files related to each of her books, proof copies of these books, and files related to her academic career, honors, awards, and memorabilia. Personal material includes her journals and diaries that depict the tenuous position of a woman in the male-dominated profession of the early seventies. -

Sister Nivedita's Ideas on Indian Nationhood and Their

Sister Nivedita’s Ideas on Indian Nationhood and their Contemporary Relevance © Vivekananda International Foundation, 2019 Vivekananda International Foundation 3, San Martin Marg, Chanakyapuri, New Delhi - 110021 Tel: 011-24121764, Fax: 011-43115450 E-mail: [email protected], Website: www.vifindia.org All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Published by Vivekananda International Foundation. | 2 Sister Nivedita’s Ideas on Indian Nationhood and their Contemporary Relevance About the Author Dr. Arpita Mitra has a doctoral degree in History from Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. She has been a Fellow (2015-2017) at the Indian Institute of Advanced Study, Shimla, where she has written a monograph on Swami Vivekananda's 'Neo-Vedanta'. Presently, she is Associate Fellow at the VIF, where she is working on different aspects of Indian history and culture. | 3 Sister Nivedita’s Ideas on Indian Nationhood and their Contemporary Relevance “We are a nation, as soon as we recognise ourselves as a nation.” ~ Sister Nivedita “…the love that Nivedita had for India was the truest of the true, not just a passing fancy. This love did not try to see the Indian scriptures validated in each action of the Indian people. Rather, it tried to penetrate all external layers to reach the innermost core of persons and to love that core. That is why she was not pained to see the extreme dereliction of India. All that was missing and inadequate in India simply aroused her love, not her censure or disrespect.” ~ Rabindranath Tagore Abstract ‘Nationalism’ has recently been a bone of contention in the Indian public sphere. -

The Dedicated

107818 SISTER NIVEDITA The Dedicated A BIOGRAPHY OF NIVEDITA by Uzelle Raymond an ASIA book THE JOHN DAY COMPANY NEW YORK. Copyright, 1953, by Lizelle Reymond All rights reserved. This book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form -without permission. Published by The John Day Company, 62 West 45th Street, New York 36, N.Y., and on the same day in Canada by Long- mans, Green & Company, Toronto. Translated from the French. The author acknowledges gratefully the aid of Katherine Woods in revising and pre- paring this book for American publication. library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 52-12681 Manufactured in the United States of America Preface SEVERAL YEARS ago, in a large city in India, I attended a theatri- cal performance by a remarkable traveling company, semi- professional, made up of some sixty children. At the end of the play the director of the company invited me to the religious service which was always celebrated by the young actors before they had their supper. On an improvised altar behind the scenes had been placed portraits of various gods, prophets, and great men: Gandhi was neighbor to Buddha, and Sri Rama- krishna's portrait stood dose to a Botticelli Madonna* Among all these serene faces, the one which most attracted my attention was that of a Western lady; and my hosts brought the picture to me so that I might look at it closely. It was an Irish* woman who had died a few years before, after devoting all her life to India: Sister Nivedita was the name she bore in India. -

Occassional Paper-2

Occasional Paper - 2 from The Library Raj Bhavan, Kolkata 19 September 2006 This Occasional Paper features English, the diarist being the first Mahatma Gandhi's last visit to this Governor of West Bengal, C. city, in August-September 1947. It Rajagopalachari (1878-1972). The also spotlights the part played by diary has been partially reproduced the Governor in the events that in a biography written by his son occurred on that visit. C.R. Narasimhan (1909-1989). We are honoured to carry a This Occasional Paper seeks reminiscence written specially for to recreate the atmosphere at us by Shri Jyoti Basu who had Beliaghata, Calcutta in the weeks called on Gandhi at of August-September 1947 Beliaghata.Saroj Mukherjee, through those two first-hand and daughter of Dr. K. N. Katju who rather little known accounts of was Governor of Orrisa (1947- diarists. 1948) and West Bengal (1948- This OP also carries excerpts 1951) and the distinguished from Narasimhan's biography of singer Juthika Roy have furnished his father and The Rajaji Story by interesting cameos. Rajmohan Gandhi. That period has been Nirmal Kumar Bose (1901- documented notably in two 1972) was central to the time spent accounts by direct witnesses and by Mahatma Gandhi in Bengal, in participants in the visit. The first 1946 and 1947. We are privileged of these is by Manu Gandhi (1927- to present in this OP a piece on 1969), a grand-niece of the NKB written for us by Professor Mahatma who wrote a daily diary André Béteille, Professor Emeritus in Gujarati which was translated of Sociology at Delhi University.