Kansas City, Kansas CLG Phase 3 Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

White House Special Files Box 45 Folder 22

Richard Nixon Presidential Library White House Special Files Collection Folder List Box Number Folder Number Document Date Document Type Document Description 45 22 n.d. Other Document Itinerary of Vice President Richard Nixon - Sept. 19 - Sept. 24, 1960. 32 pages. Wednesday, May 23, 2007 Page 1 of 1 t I 1• STRICTLY CONFIDENTIAL ITINERARY OF VICE PRESIDENT RICHARD NIXON September 19 through September 24. 1960 Monday. September 19 Convair Aircraft 3:15 PM EDT Depart Washington National Airport enroute (200 mi. -1:15) to Wilkes-Barre - Scranton Airport 4:30 PM EDT Arrive Wilkes-Barre - Scranton Airport. AM: John located near Avoca. Pa, Whitaker Population of Wilkes-Barre is 90.000 U. S. Senator for Pennsylvania is Hugh Scott Candidates for Congress are: Dr. Donald Ayers (11th District) William Scranton (10th District) Edwin M. Kosik is in charge of arrangements Reception Committee: Lester Burl ein, Chairman 10th Congressional District Mrs. Audrey Kelly, Represents Women of 10th District J. Julius Levy. former United States Attorney Donald Sick. Chairman Young Republicans. Wyoming County Charles" Harte. Minority Commissioner. Lackawanna County Miss Gail Harris. Vice Chairman, Lackawanna County Flowers for Mrs. Nixon presented by Gail Harris, Vice Chairman. Lackawanna County Joseph Smith is Motorcade Chairman 4:59 PM Depart airport by motorcade enroute to Wilkes-Barre via Thruway 5: 15 PM ARRIVE CITY SQUARE Bad weather alternative: Masonic Auditorium Page 1 Page 2 Monday, September 19 (continued) Platform Committee: Former Governor John Fine Former Governor Arthur James Joe Gale, County Chairman Mrs. Mina McCracken, Vice Chairman, Luzerne County Max Rosen, Luzerne County Nixon-Lodge Volunteers Chairman Former State Senator Andrew Sardoni Dr. -

Kansas City Star Magazine Collection (K0595)

THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MISSOURI RESEARCH CENTER-KANSAS CITY K0595 Kansas City Star Magazine Collection [Native Sons Archives] 1924-1926 .3 cubic foot A near complete set of the short-lived art and culture magazine published by the Kansas City Star newspaper. HISTORY: A special project of Laura Nelson Kirkwood, the magazine was printed in Germany and illustrated by well-known artists. It proved too expensive to continue publication. PROVENANCE: This gift was received from The Native Sons of Kansas City as part of accession KA0590 on July 17, 1990. COPYRIGHT AND RESTRICTIONS: The Donor has given and assigned to the State Historical Society of Missouri all rights of copyright which the Donor has in the Materials and in such of the Donor’s works as may be found among any collections of Materials received by the Society from others. PREFERRED CITATION: Specific item; folder number; The Kansas City Star Magazine Collection (K0595); The State Historical Society of Missouri Research Center-Kansas City [after first mention may be abbreviated to SHSMO-KC]. CONTACT: The State Historical Society of Missouri Research Center-Kansas City 302 Newcomb Hall, University of Missouri-Kansas City SHSMO-KC August 29, 2013 PRELIMINARY K0595 The Kansas City Star Magazine Collection Page 2 5123 Holmes Street, Kansas City, MO 64110-2499 (816) 235-1543 [email protected] http://shs.umsystem.edu/index.shtml DESCRIPTION: The collection includes original magazine publications. Included in each publication are: a study and description of the cover art or other famous works of art; short stories and serials; articles about famous people, some with local connections; photographs of area homes, people, events; photographs of national or international interest; society news; fashion illustrations by Edna Marie Dunn; illustrated poetry and cartoons by Dale Beronius; and advertisements for local businesses. -

Louis Edward Holland (1878-1960) Papers (K0019)

THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MISSOURI RESEARCH CENTER-KANSAS CITY K0019 Louis Edward Holland (1878-1960) Papers ca. 1916-1960 210 cubic feet Papers documenting the public career of Louis E. Holland, long-time friend of President Harry S. Truman. Holland, a Kansas City businessman, was actively involved in national transportation issues-particularly the automobile and airplane, advertising and publishing. BIOGRAPHY: Louis Edward Holland was born in Parma, New York, June 20, 1878. He was educated in the public schools in Rochester, New York. In 1901 Holland married Adelia Garrett. The next year they moved to Kansas City where Holland, a machinist who learned photo-engraving on the job at the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, had a position with Thompson and Slaughter Engraving Company. Soon he went to work for Teachenor and Bartberger, the largest engraving business in Kansas City. He built a reputation of quality work for the local advertising agencies, many of whom contributed monies to help him organize the Holland Engraving Company in 1916. Holland was president of the Kansas City Chamber of Commerce, 1925-27; and managing director, 1928-31. During his tenure with the Chamber, Holland: helped get Kansas City on the first air mail route by contract carriers; promoted the establishment of the Kansas City Municipal Airport; and convinced an airline, the forerunner of Trans World Airlines (TWA) to establish their headquarters here. Holland was president of the Associated Advertising Clubs of the World, 1922-25, and chairman of the committee that set up the National Better Business bureau. In December of 1929, Adelia Holland died after a long illness. -

Beautiful and Damned: Geographies of Interwar Kansas City by Lance

Beautiful and Damned: Geographies of Interwar Kansas City By Lance Russell Owen A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geography in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Michael Johns, Chair Professor Paul Groth Professor Margaret Crawford Professor Louise Mozingo Fall 2016 Abstract Beautiful and Damned: Geographies of Interwar Kansas City by Lance Russell Owen Doctor of Philosophy in Geography University of California, Berkeley Professor Michael Johns, Chair Between the World Wars, Kansas City, Missouri, achieved what no American city ever had, earning a Janus-faced reputation as America’s most beautiful and most corrupt and crime-ridden city. Delving into politics, architecture, social life, and artistic production, this dissertation explores the geographic realities of this peculiar identity. It illuminates the contours of the city’s two figurative territories: the corrupt and violent urban core presided over by political boss Tom Pendergast, and the pristine suburban world shaped by developer J. C. Nichols. It considers the ways in which these seemingly divergent regimes in fact shaped together the city’s most iconic features—its Country Club District and Plaza, a unique brand of jazz, a seemingly sophisticated aesthetic legacy written in boulevards and fine art, and a landscape of vice whose relative scale was unrivalled by that of any other American city. Finally, it elucidates the reality that, by sustaining these two worlds in one metropolis, America’s heartland city also sowed the seeds of its own destruction; with its cultural economy tied to political corruption and organized crime, its pristine suburban fabric woven from prejudice and exclusion, and its aspirations for urban greatness weighed down by provincial mindsets and mannerisms, Kansas City’s time in the limelight would be short lived. -

Wilson, Francis M. (1867-1932), Papers, 1853-1946 1039 27.4 Linear Feet, 14 Volumes

C Wilson, Francis M. (1867-1932), Papers, 1853-1946 1039 27.4 linear feet, 14 volumes This collection is available at The State Historical Society of Missouri. If you would like more information, please contact us at [email protected]. INTRODUCTION Papers of a U.S. district attorney, receiver for the Kansas City Railways Company, and Democratic nominee for governor of Missouri in 1928 and 1932, who died a month before the election of 1932. Also papers concerning his father, R.P.C. Wilson, I. DONOR INFORMATION The papers were deposited with the University of Missouri by Francis M. Wilson II on 19 October 1957 (Accession No.3329). An addition was made on 21 December 1958 by Francis M. Wilson II (Accession No.3374). BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Francis Murray Wilson was born in Platte County, Missouri, on June 13, 1867. His family was prominent in the history of the state. His father, Robert P.C. Wilson, lawyer, served as U.S. Congressman from Missouri from 1889-1893. His mother was Caroline F. Murray. Francis Wilson’s grandfather, John Wilson, served Missouri as a pioneer lawyer. After growing to boyhood in Platte County, Francis graduated from Vanderbilt University and Centre College. Returning to Platte County, he read law in his father’s office and worked in Kansas City as a stenographer for Pratt, McCreary and Perry. He started practicing law in 1889 at the age of 29. He served as city attorney of Platte County from 1894-1898, and in 1899, he was appointed Missouri State Senator to fill an unexpired term. -

George Ehrlich Papers, (K0067

THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MISSOURI RESEARCH CENTER-KANSAS CITY K0067 George Ehrlich Papers 1946-2002 65 cubic feet, oversize Research and personal papers of Dr. George Ehrlich, professor of Art and Art History at the University of Missouri-Kansas City and authority on Kansas City regional architecture. DONOR INFORMATION The papers were donated by Dr. George Ehrlich on August 19, 1981 (Accession No. KA0105). Additions were made on July 23, 1982 (Accession No. KA0158); April 7, 1983 (Accession No. KA0210); October 15, 1987 (Accession No. KA0440); July 29, 1988 (Accession No. KA0481); July 26, 1991 (Accession No. KA0640). An addition was made on March 18, 2010 by Mila Jean Ehrlich (Accession No. KA1779). COPYRIGHT AND RESTRICTIONS The Donor has given and assigned to the University all rights of copyright, which the Donor has in the Materials and in such of the Donor’s works as may be found among any collections of Materials received by the University from others. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Dr. George Ehrlich, emeritus professor of Art History at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, was born in Chicago, Illinois, on January 28, 1925. His education was primarily taken at the University of Illinois, from which he received B.S. (Honors), 1949, M.F.A., 1951, and Ph.D., 1960. His studies there included art history, sculpture, architecture, history, and English literature. Dr. Ehrlich served as a member of the United States Army Air Force, 1943- 1946. He was recalled to active duty, 1951-1953 as a First Lieutenant. Dr. Ehrlich joined the faculty at the University of Missouri-Kansas City in 1954. -

Nelly Don: an Educational Leader

Lindenwood University Digital Commons@Lindenwood University Dissertations Theses & Dissertations Spring 4-2018 Nelly Don: An Educational Leader Lisa S. Thompson Lindenwood University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lindenwood.edu/dissertations Part of the Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons Recommended Citation Thompson, Lisa S., "Nelly Don: An Educational Leader" (2018). Dissertations. 192. https://digitalcommons.lindenwood.edu/dissertations/192 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses & Dissertations at Digital Commons@Lindenwood University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Lindenwood University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nelly Don: An Educational Leader by Lisa S. Thompson A Dissertation submitted to the Education Faculty of Lindenwood University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education School of Education Nelly Don: An Educational Leader by Lisa S. Thompson This dissertation has been approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education at Lindenwood University by the School of Education Declaration of Originality I do hereby declare and attest to the fact that this is an original study based solely upon my own scholarly work here at Lindenwood University and that I have not submitted it for any other college or university course or degree here or elsewhere. Full Legal Name: Lisa Sonya Thompson Acknowledgements I would first like to thank Dr. Joseph Alsobrook and Dr. John Long. It was their leadership and guidance that allowed for a contract degree comprised of coursework from both Educational Leadership and Fashion Design programs. -

H. Doc. 108-222

EIGHTY-FIRST CONGRESS JANUARY 3, 1949, TO JANUARY 3, 1951 FIRST SESSION—January 3, 1949, to October 19, 1949 SECOND SESSION—January 3, 1950, to January 2, 1951 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—ALBEN W. BARKLEY, of Kentucky PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—KENNETH D. MCKELLAR, 1 of Tennessee SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—LESLIE L. BIFFLE, 1 of Arkansas SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—JOSEPH C. DUKE, 1 of Arizona SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—SAM RAYBURN, 1 of Texas CLERK OF THE HOUSE—RALPH R. ROBERTS, 1 of Indiana SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—JOSEPH H. CALLAHAN, 1 of Kentucky DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—WILLIAM M. MILLER, 1 of Mississippi POSTMASTER OF THE HOUSE—FINIS E. SCOTT, 1 of Tennessee ALABAMA Wilbur D. Mills, Kensett Helen Gahagan Douglas, Los SENATORS James W. Trimble, Berryville Angeles Lister Hill, Montgomery Boyd Tackett, Nashville Gordon L. McDonough, Los Angeles John J. Sparkman, Huntsville Brooks Hays, Little Rock Donald L. Jackson, Santa Monica Cecil R. King, Los Angeles REPRESENTATIVES W. F. Norrell, Monticello Oren Harris, El Dorado Clyde Doyle, Long Beach Frank W. Boykin, Mobile Chet Holifield, Montebello George M. Grant, Troy CALIFORNIA Carl Hinshaw, Pasadena George W. Andrews, Union Springs SENATORS Harry R. Sheppard, Yucaipa Sam Hobbs, Selma Albert Rains, Gadsden Sheridan Downey, 2 San Francisco John Phillips, Banning Edward deGraffenried, Tuscaloosa Richard M. Nixon, 3 Whittier Clinton D. McKinnon, San Diego Carl Elliott, Jasper William F. Knowland, Piedmont COLORADO Robert E. Jones, Jr., Scottsboro REPRESENTATIVES SENATORS Laurie C. Battle, Birmingham Hubert B. Scudder, Sebastopol Clair Engle, Red Bluff Edwin C. -

Planning and Urban Design

Planning and Urban Design 701 North 7th Street, Room 423 Phone: (913) 573-5750 Kansas City, Kansas 66101 Fax: (913) 573-5796 Email: [email protected] www.wycokck.org/planning To: Unified Government Board of Commissioners From: Planning and Urban Design Staff Date: August 27, 2020 Re: MP-2020-6 GENERAL INFORMATION Applicant: Ryan Conk Status of Applicant: Representative KC The Yards 2, LLC One Indiana Square, Suite 3000 Indianapolis, Indiana 46202 N Requested Actions: Master Plan Amendment from Industrial to Mixed Use. Date of Application: June 26, 2020 Purpose: To amend the City-Wide Master Plan Land Use N designation from Industrial to Mixed Use in order to allow for future mixed-use development. Property Location: 200 South James Street N MP-2020-6 August 27, 2020 1 Commission Districts: District Commissioner: Brian McKiernan Commissioner At Large: Tom Burroughs Existing Zoning: M-3 Heavy Industrial District Adjacent Zoning: North: M-3 Heavy Industrial District South: M-3 Heavy Industrial District East: Kansas City, Missouri West: Kansas River Adjacent Uses: North: Business campus parking South: Industrial business East: Parking lots and garage (Missouri) West: Kansas River Total Tract Size: 17.37 Acres Master Plan Designation: The City-Wide Master Plan designates this property as Industrial. Major Street Plan: The Citywide Master Plan designates James Street as a Class B Thoroughfare. However, the applicant property can only be accessed by a portion of State Line Road that lies completely in Kansas City, Jackson County, Missouri. Required Parking: Section 27-470(f) requires no less than one (1) space per 500 square feet of building area provided. -

4490Annual Report Nyc Dept P

DEPARTMENTOF PARKS, CITY OF NEW YORK. ANNUAL REPORT 8 FOR THE YE.4R ENDING DECEMBER 31, 1899. COMMISSIONERS : GEORGE C. CLAUSEN (President), Boroughs of Manhattan and Richmond. AUGUST MOEBUS, Borough of The Bronx. GEORGE V. BROWER, Boroughs of Brooklyn and Queens. Landscape Architect, JOHNDEWOLF. Secretary, W1LLl.S HOLLY. NEW YORK: MARTIN B. RROWN CO., PRINTERS AND STATIONERS, Nos. 49 TO 57 PARKPLACE. -- 1900. DEPARTMENT OF PARKS. REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDING DECEMBER 31, 1899, DEPARTMENTOF PARKS-CITY OF NEW YORK, THEARSENAL, CENTRAL PARK, January 2, 1900. Non. ROBERTA. VAN WYCK,Mayor : SIR-I have the honor to send herewith the annual reports of the Commissioners of Parks, of the operations of the Department in the borough divisions over which they have administrative jurisdiction, for the year 1899. Very respectfully yours, WILLIS HOLLY, Secretary, Park Board SCHEDULE. I. Manhattan and Richmond. / 3. Brooklyn and Queens. 2. The Bronx. 1 4. Addenda. DEPARTMENTOF PARKS-CITY OF NEW YORK,) THEARSENAL, CENTRAL PARK, January 2, Ip. { Hon. ,ROBERTA. VANWYCK, Mayor: SIR-I have the honor to transmit herewith my report of the operations of the Department of Parks, Boroughs of Manhattan and Richmond, for the year 1899. A notable administration feature of the year's work of the Department in these boroughs was the reception tendered by the citizens of New York to Admiral Dewey on his return from the Philippines. In this great popular demonstration the Deparlment was vitally concerned, as the site of the memorial arch, erected.in honor of the naval heroes, was within the jur~sdictionof the Department and most of the stand provision, at the reviewing point and other places along the line of march, had to be made on ground belonging to the park system. -

Wall Street 1987

WALL STREET ORIGINAL STORY AND SCREENPLAY BY STANLEY WEISER AND OLIVER STONE FIRST DRAFT EDWARD P~ESSMA.N PRODUCTIONS January 31, 1987 1 • EXT. WALL STREET - EARLY MORNING FADE IN. THE STREET. The most famous third of a mile in the world. Towering landmark structures nearly blot out the dreary grey flannel sky. The morning rush hour crowds swarm through the dark, narrow streets like mice in a maze, all in pursuit of one thing: MONEY... CREDITS run. INT. SUBWAYPLATFORM - EARLY MORNING we hear the ROAR of the trains pulling out of the station. Blurred faces, bodies, suits, hats, attache cases float into view pressed like sardines against the sides of a door which now open, releasing an outward velocity of anger and greed, one of them JOE FOX. EXT. SUBWAYEXIT - MORNING The bubbling mass charges up the stairs. Steam rising from a grating, shapes merging into the crowd. Past the HOMELESS VETS, the insane BAG LADY with 12 cats and 20 shopping bags huddled in the corner of Trinity Church .•. Joe the Fox straggling behind, in a crumpied raincoat, tie askew, young, very young, his bleary face buried in~ Wall Street Journal, as he crosses the street against the light. JOE Why Fox? Why didn't you buy ... schmuck A car honks, swerving past. INT. OFFICE BUILDING - DAY Cavernous modern lobby. Bodies cramming into elevators. Joe, stuffing the newspaper into his coat, jams in. INT. ELEVATOR - MORNING Blank faces stare ahead, each lost in private thoughts, Joe again mouthing the thought, "stupid schmuck", his· ,:yes catching a blonde executive who quickly flicks her eyes away. -

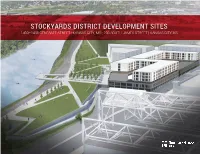

Stockyards District Development Sites 1400–1430 Genessee Street | Kansas City, Mo ; 200 South James Street | Kansas City, Ks

STOCKYARDS DISTRICT DEVELOPMENT SITES 1400–1430 GENESSEE STREET | KANSAS CITY, MO ; 200 SOUTH JAMES STREET | KANSAS CITY, KS TABLE OF CONTENTS 01 02 03 EXECUTIVE PROPERTY MARKET SUMMARY OVERVIEW OVERVIEW EXECUTIVE SUMMARY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SITE BOUNDARY Newmark Grubb Zimmer (NGZ) is pleased to present the opportunity to purchase LEVEE EASMENTS development ground located in the Stockyards District of Kansas City, Missouri and Kansas City, EXISTING WALLS Kansas. The property totals 17.365 acres of raw ground that can be split up to accommodate OTHER PARCELS multiple developments and uses, making it a prime site for urban mixed-use projects. Located on the Kansas side of the State Line, the property fronts the Kansas River to the West, and the Stockyards District to the East. Additionally, 3.4 acres are available in Kansas City, Missouri on Genessee Street located directly next to I-670. 1400-1430 Genessee Street, Kansas City, MO Location Stockyards District Zone M3-5, Urban Development Available 1.50 Acres Available 1.81 Acres 200 South James Street, Kansas City, KS Location Stockyards District 17.365 Acres Total Divisible/Flexible Available Sites 6 STOCKYARDS DISTRICT DEVELOPMENT SITES PROPERTY OVERVIEW River Market West Bottoms 1400-1430 GENESSEE STREET KANSAS CITY | MO Downtown Kansas City 200 SOUTH JAMES STREET KANSAS CITY | KS HyVee Arena American Royal 32 10 property Name HISTORY Since the establishment of the Kansas City Stockyards in 1871, the Stockyards District has been a booming area of business and commerce, ranging from millions of head of cattle trading per year, to recently 9 developed mixed-use projects including office, industrial, multifamily, and recreational uses.