Judicial Clerkship Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fellows of the American Bar Foundation

THE FELLOWS OF THE AMERICAN BAR FOUNDATION 2015-2016 2015-2016 Fellows Officers: Chair Hon. Cara Lee T. Neville (Ret.) Chair – Elect Michael H. Byowitz Secretary Rew R. Goodenow Immediate Past Chair Kathleen J. Hopkins The Fellows is an honorary organization of attorneys, judges and law professors whose pro- fessional, public and private careers have demonstrated outstanding dedication to the welfare of their communities and to the highest principles of the legal profession. Established in 1955, The Fellows encourage and support the research program of the American Bar Foundation. The American Bar Foundation works to advance justice through ground-breaking, independ- ent research on law, legal institutions, and legal processes. Current research covers meaning- ful topics including legal needs of ordinary Americans and how justice gaps can be filled; the changing nature of legal careers and opportunities for more diversity within the profession; social and political costs of mass incarceration; how juries actually decide cases; the ability of China’s criminal defense lawyers to protect basic legal freedoms; and, how to better prepare for end of life decision-making. With the generous support of those listed on the pages that follow, the American Bar Founda- tion is able to truly impact the very foundation of democracy and the future of our global soci- ety. The Fellows of the American Bar Foundation 750 N. Lake Shore Drive, 4th Floor Chicago, IL 60611-4403 (800) 292-5065 Fax: (312) 564-8910 [email protected] www.americanbarfoundation.org/fellows OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS OF THE Rew R. Goodenow, Secretary AMERICAN BAR FOUNDATION Parsons Behle & Latimer David A. -

One Man's Token Is Another Woman's Breakthrough - the Appointment of the First Women Federal Judges

Volume 49 Issue 3 Article 2 2004 One Man's Token is Another Woman's Breakthrough - The Appointment of the First Women Federal Judges Mary L. Clark Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr Part of the Judges Commons Recommended Citation Mary L. Clark, One Man's Token is Another Woman's Breakthrough - The Appointment of the First Women Federal Judges, 49 Vill. L. Rev. 487 (2004). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr/vol49/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Villanova Law Review by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Clark: One Man's Token is Another Woman's Breakthrough - The Appointment 2004] Article ONE MAN'S TOKEN IS ANOTHER WOMAN'S BREAKTHROUGH? THE APPOINTMENT OF THE FIRST WOMEN FEDERAL JUDGES MARY L. CLARK* I. INTRODUCTION NIO women served as Article III judges in the first one hundred and fifty years of the American republic.' It was not until Franklin Del- ano Roosevelt named Florence Ellinwood Allen to the U.S. Court of Ap- peals in 1934 that women were included within the ranks of the federal 2 judiciary. This Article examines the appointment of the first women federal judges, addressing why and how presidents from Roosevelt through Ford named women to the bench, how the backgrounds and experiences of these nontraditional appointees compared with those of their male col- leagues and, ultimately, why it matters that women have been, and con- tinue to be, appointed. -

Miriam G. Cederbaum.2.2

IN MEMORIAM: JUDGE MIRIAM GOLDMAN CEDARBAUM Sonia Sotomayor * Miriam Cedarbaum had been a judge on the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York for six years when I joined that court in 1992. I count myself as lucky for so many reasons, but getting to serve alongside and learn from Judge Cedarbaum falls high on that list. Judge Cedarbaum mentored me in my first few years on the bench and served as a steady source of strength and wisdom in the years after. This relationship began when she stopped by my office during my first week on the bench, a tradition she followed with every new judge on her court. It continued afterwards because our offices were on the same floor of the Thurgood Marshall Courthouse, just around the corner, and we kept the same arrangement when renovations moved us to the Daniel Patrick Moynihan Courthouse. I learned much from Judge Cedarbaum. In this space, I want to record those lessons so that other judges, those not fortunate enough to be paid a visit by her during their first week on the bench, can learn from her still. Be careful. A district court judge labors in the boiler room of our judicial system. Alarms constantly sound, work never stops, and thanks rarely materialize. While toiling away, a district court judge may be tempted to cut corners, to make the job just a little easier. Not Judge Cedarbaum. Read any one of Judge Cedarbaum’s decisions and her attention to the facts and mastery of the legal issues leap off the page. -

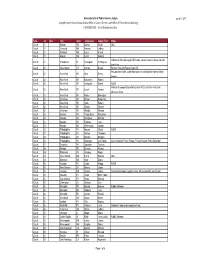

Anecdotal List of Public Interest Judges Compiled by the Harvard

Anecdotal List of Public Interest Judges as of 11/3/17 Compiled by the Harvard Law School Office of Career Services and Office of Public Interest Advising. CONFIDENTIAL - for HLS Applicants Only Type Cir Dist City State Judge Last Judge First Notes Circuit 01 Boston MA Barron David OLC Circuit 01 Concord NH Howard Jeffrey Circuit 01 Portland ME Lipez Kermit Circuit 01 Boston MA Lynch Sandra Worked at Harvard Legal Aid Bureau; started career in legal aid and Circuit 01 Providence RI Thompson O. Rogeree family law Circuit 02 New Haven CT Carney Susan Former Yale and Peace Corps GC Has partnered with Judge Katzmann on immigration representation Circuit 02 New York NY Chin Denny project Circuit 02 New York NY Katzmann Robert Circuit 02 New York NY Livingston Debra AUSA Worked as cooperating attorney with ACLU and New York Civil Circuit 02 New York NY Lynch Gerard Liberties Union Circuit 02 New York NY Parker Barrington Circuit 02 Syracuse NY Pooler Rosemary Circuit 02 New York NY Sack Robert Circuit 02 New York NY Straub Chester Circuit 02 Geneseo NY Wesley Richard Circuit 03 Newark NJ Trump Barry Maryanne Circuit 03 Newark NJ Chagares Michael Circuit 03 Newark NJ Fuentes Julio Circuit 03 Newark NJ Greenaway Joseph Circuit 03 Philadelphia PA Krause Cheryl AUSA Circuit 03 Philadelphia PA McKee Theodore Circuit 03 Philadelphia PA Rendell Marjorie Circuit 03 Philadelphia PA Restrepo Luis Felipe ACLU National Prison Project; Former Federal Public Defender Circuit 03 Scranton PA Vanaskie Thomas Circuit 04 Raleigh NC Duncan Allyson Circuit 04 Richmond -

Master of Laws

APPLYING FOR & FINANCING YOUR LLM MASTER OF LAWS APPLICATION REQUIREMENTS APPLICATION CHECKLIST Admission to the LLM program is highly For applications to be considered, they must include the following: competitive. To be admitted to the program, ALL APPLICANTS INTERNATIONAL APPLICANTS applicants must possess the following: • Application & Application Fee – apply • Applicants with Foreign Credentials - For electronically via LLM.LSAC.ORG, and pay applicants whose native language is not • A Juris Doctor (JD) degree from an ABA-accredited non-refundable application fee of $75 English and who do not posses a degree from law school or an equivalent degree (a Bachelor of Laws • Official Transcripts: all undergraduate and a college or university whose primary language or LL.B.) from a law school outside the United States. graduate level degrees of instruction is English, current TOEFL or IELTS • Official Law School or Equivalent Transcripts scores showing sufficient proficiency in the • For non-lawyers interested in the LLM in Intellectual • For non-lawyer IP professionals: proof of English language is required. The George Mason Property (IP) Law: a Bachelor’s degree and a Master’s minimum of four years professional experience University Scalia Law School Institution code degree in another field, accompanied by a minimum in an IP-related field is 5827. of four years work experience in IP may be accepted in • 500-Word Statement of Purpose • TOEFL: Minimum of 90 in the iBT test lieu of a law degree. IP trainees and Patent Examiners • Resume (100 or above highly preferred) OR (including Bengoshi) with four or more years of • Letters of Recommendation (2 required) • IELTS: Minimum of 6.5 (7.5 or above experience in IP are welcome to apply. -

Journeyaugust 2019 the MAGAZINE of ST. PAUL LUTHERAN CHURCH

journey THE MAGAZINE OF ST. PAUL LUTHERAN CHURCH August 2019 Journey | August 2019 1 PASTOR’S column Yellow buttercups He wore one of those flimsy gowns as he sat in the green recliner of his hospi- tal room. My friend isn’t used to sitting still. He normally walks a couple miles a day. His mind is what I call kitchen knife sharp, which is I didn’t know what a close cousin of razor sharp. On this day, he wasn’t talk- a yellow buttercup was. ing much, though. The nurse had resecured the oxygen Floral typology isn’t my tube over his 78-year old ears, and that plastic tube was strong suit, anymore pumping life straight into his nostrils. than bringing home At one point during my conversation with his wife, flowers to my wife is George spoke up and I turned to listen. “You know,” he (she will tell you). But said, “two days ago, who would’ve guessed I’d be here? I was pretty sure the Life was happening. I never think about all the things flower is yellow, and that have to work inside my body every hour of every resembling of a cup, day. Organs functioning synchronistically. Chemical which sounds an awful levels in line. Blood producing the right kind of cells in lot like a tulip; though the right kind of numbers. It’s not until something big it’s not that, which I learned online moments ago. happens that we suddenly realize how dependent we This morning I made a hospice call. -

A Streamlined Model of Tribal Appellate Court Rules for Lay Advocates and Pro Se Litigants

American Indian Law Journal Volume 4 Issue 1 Article 4 12-15-2015 A Streamlined Model of Tribal Appellate Court Rules for Lay Advocates and Pro Se Litigants Gregory D. Smith J.D. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/ailj Part of the Courts Commons, and the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Gregory D. J.D. (2015) "A Streamlined Model of Tribal Appellate Court Rules for Lay Advocates and Pro Se Litigants," American Indian Law Journal: Vol. 4 : Iss. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/ailj/vol4/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications and Programs at Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian Law Journal by an authorized editor of Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. A Streamlined Model of Tribal Appellate Court Rules for Lay Advocates and Pro Se Litigants Cover Page Footnote Gregory D. Smith, [J.D., Cumberland School of Law, 1988; B.S., Middle Tennessee State University, 1985; Special Courts Certification, National Judicial College, 2014], is a Justice on the Pawnee Nation Supreme Court in Oklahoma and the Alternate Judge on the Gila River Indian Community Court of Appeals in Arizona. Each court is the highest appellate court in their respective tribal nations. Both positions are part-time judgeships. Mr. Smith also has a law practice in Clarksville, Tennessee and is the part-time municipal judge for Pleasant View, Tennessee. Judge Smith has presented between 650–700 appeals for courts all over the United States. -

Joint Public Health and Law Programs

JOINT PUBLIC HEALTH AND LAW tuition rate and fees are charged for semesters when no Law School courses are taken, including summer sessions. PROGRAMS Visit the Hirsh Program website (http://publichealth.gwu.edu/ Program Contact: J. Teitelbaum programs/joint-jdllm-mphcertificate/) for additional information. The Milken Institute of School of Public Health (SPH), through its Hirsh Health Law and Policy Program, cooperates with the REQUIREMENTS Law School to offer public health and law students multiple programs that foster an interdisciplinary approach to the study MPH requirements in the joint degree programs of health policy, health law, public health, and health care. The course of study for the standalone MPH degree, in one of Available joint programs include the master of public health several focus areas, (http://publichealth.gwu.edu/node/766/) (http://bulletin.gwu.edu/public-health/#graduatetext) (MPH) consists of 45 credits, including a supervised practicum. In the and juris doctor (https://www.law.gwu.edu/juris-doctor/) (JD); dual degree programs with the Law School, the Milken Institute MPH and master of laws (https://www.law.gwu.edu/master- School of Public Health (GWSPH) accepts 8 Law School credits of-laws/) (LLM); and JD or LLM and SPH certificate in various toward completion of the MPH degree. Therefore, Juris doctor subject areas. LLM students may be enrolled in either the (JD) and master of laws (LLM) students in the dual program general or environmental law program at the Law School. complete only 37 credits of coursework through GWSPH to obtain an MPH degree. Application of credits between programs Depending upon the focus area in which a JD student chooses For the JD/MPH, 8 JD credits are applied toward the MPH and to study, as a rule, the joint degree can be earned in three- up to 12 MPH credits may be applied toward the JD. -

Montgomery County Circuit Court FY 2015 Annual Statistical Digest

FY2015 Statistical Digest Montgomery County Circuit Court Administrative Office of Montgomery County Circuit Court 1 Table of Contents Ensuring Accountability and Public Trust: Continual, Collaborative Review of Court Performance ........................................................................................................................ 2 Montgomery County and Circuit Court Statistics............................................................ 3 Population of Montgomery County ................................................................................................... 3 Racial and Ethnic Diversity - Minorities are Majority Population ................................................... 5 Increase in Foreign-Born Residents ................................................................................................. 7 Maturing County Population ...........................................................................................................14 Crime Statistics ................................................................................................................................ 17 Domestic Violence Statistics ........................................................................................................... 23 Workload and Case Processing Analysis .......................................................................... 26 Workload Analysis ........................................................................................................................... 26 Case Processing Analysis -

AFRA AFSHARIPOUR University of California, Davis, School of Law

AFRA AFSHARIPOUR University of California, Davis, School of Law 400 Mrak Hall Drive, Davis, California 95616 (530) 754-0111 (work) • [email protected] _________________________________________________________________________________________ ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, DAVIS, SCHOOL OF LAW Davis, CA Senior Associate Dean for Academic Affairs July 2018-present Professor of Law (Acting Professor of Law July 2007-June 2012) July 2007-present Courses: Business Associations, Mergers and Acquisitions, Startups & Venture Capital, Corporate Governance, Antitrust, Business Planning Research: Comparative Corporate Law, Corporate Governance, Mergers and Acquisitions, Securities Regulation, Transactional Law RESEARCH AND VISITING POSITIONS CHINA UNIVERSITY OF POLITICAL SCIENCE AND LAW (CUPL) Beijing, China Visiting Scholar – Legal Experts Forum May 2019 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY, SCHOOL OF LAW Berkeley, CA Visiting Fellow, Berkeley Center for Law, Business and the Economy (BCLBE) August 2016-May 2017 NATIONAL CHIAO-TUNG UNIVERSITY Hsinchu City, Taiwan Visiting Scholar January 2017 NATIONAL LAW SCHOOL OF INDIA UNIVERSITY Bangalore, India Visiting Scholar June 2010 OTHER PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE DAVIS POLK & WARDWELL New York, NY and Menlo Park, CA Associate Summer 1998, October 2000-July 2007 Corporate: Advised clients on domestic and cross border mergers and acquisitions, public and private securities offerings, corporate governance and compliance matters, and bank regulatory matters. Pro Bono: Awarded State Bar -

The 2021-2022 Guide to State Court Judicial Clerkship Procedures

The 2021-2022 Guide to State Court Judicial Clerkship Procedures The Vermont Public Interest Action Project Office of Career Services Vermont Law School Copyright © 2021 Vermont Law School Acknowledgement The 2021-2022 Guide to State Court Judicial Clerkship Procedures represents the contributions of several individuals and we would like to take this opportunity to thank them for their ideas and energy. We would like to acknowledge and thank the state court administrators, clerks, and other personnel for continuing to provide the information necessary to compile this volume. Likewise, the assistance of career services offices in several jurisdictions is also very much appreciated. Lastly, thank you to Elijah Gleason in our office for gathering and updating the information in this year’s Guide. Quite simply, the 2021-2022 Guide exists because of their efforts, and we are very appreciative of their work on this project. We have made every effort to verify the information that is contained herein, but judges and courts can, and do, alter application deadlines and materials. As a result, if you have any questions about the information listed, please confirm it directly with the individual court involved. It is likely that additional changes will occur in the coming months, which we will monitor and update in the Guide accordingly. We believe The 2021-2022 Guide represents a necessary tool for both career services professionals and law students considering judicial clerkships. We hope that it will prove useful and encourage other efforts to share information of use to all of us in the law school career services community. -

Keeping the Judicial Law Clerk on Your Side

APPELLATE ADVOCACY Help the Clerk and Help Your Case Keeping the Judicial Law Clerk By Amanda E. Heitz on Your Side Although appellate Apart from the litigants and attorneys themselves, there practice articles often likely is nobody who will spend more time poring over cover how to write your briefs and the record than a judicial law clerk. At a briefs and motions for minimum, the judges deciding your case will rely on their clerks’ analyses of the record and research tifying the important legal issues and facts judges, we can forget of the issues—and many will also lean on on which an opinion will rely. Making an these clerks to propose an outcome and enemy of the law clerk may not sink your that our audience also craft language for written opinions. case, but it certainly will never help you. The role of law clerks in the judicial And keeping the law clerk on your side will includes law clerks, and process has been the subject of scholarly you give you another voice in chambers research and discussion for years. See, e.g., who can remind the judge of strong facts importantly, we need Stephen L. Wasby, The World of Law Clerks: or law that help your position. Tasks, Utilization, Reliance, and Influence, Accordingly, this article intends to pro- to help them focus on 98 Marq. L. Rev. 111 (2014); Todd C. Pep- vide practical tips from former law clerk pers et al., Inside Judicial Chambers: How perspectives that can help make you a bet- our arguments, too.