Poetryjosephine00milerich.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bookman Anthology of Verse

The Bookman Anthology Of Verse Edited by John Farrar The Bookman Anthology Of Verse Table of Contents The Bookman Anthology Of Verse..........................................................................................................................1 Edited by John Farrar.....................................................................................................................................1 Hilda Conkling...............................................................................................................................................2 Edwin Markham.............................................................................................................................................3 Milton Raison.................................................................................................................................................4 Sara Teasdale.................................................................................................................................................5 Amy Lowell...................................................................................................................................................7 George O'Neil..............................................................................................................................................10 Jeanette Marks..............................................................................................................................................11 John Dos Passos...........................................................................................................................................12 -

Donahue Poetry Collection Prints 2013.004

Donahue Poetry Collection Prints 2013.004 Quantity: 3 record boxes, 2 flat boxes Access: Open to research Acquisition: Various dates. See Administrative Note. Processed by: Abigail Stambach, June 2013. Revised April 2015 and May 2015 Administrative Note: The prints found in this collection were bought with funds from the Carol Ann Donahue Memorial Poetry endowment. They were purchased at various times since the 1970s and are cataloged individually. In May 2013, it was transferred to the Sage Colleges Archives and Special Collections. At this time, the collection was rehoused in new archival boxes and folders. The collection is arranged in call number order. Box and Folder Listing: Box Folder Folder Contents Number Number Control Folder 1 1 ML410 .S196 C9: Sports et divertissements by Erik Satie 1 2 N620 G8: Word and Image [Exhibition] December 1965, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum 1 3 N6494 .D3 H8: Dada Manifesto 1949 by Richard Huelsenbeck 1 4 N6769 .G3 A32: Kingling by Ian Gardner 1 5 N7153 .T45 A3 1978X: Drummer by Andre Thomkins 1 6 NC790 .B3: Landscape of St. Ives, Huntingdonshire by Stephen Bann 1 7 NC1820 .R6: Robert Bly Poetry Reading, Unicorn Bookshop, Friday, April 21, 8pm 1 8 NC1850 .P28 P3 V.1: PN2 Experiment 1 9 NC1850 .P28 P3 V.2: PN2 Experiment 1 10 NC1850 .P28 P3 V.4: PN2 Experiment 1 11 NC1850 .P28 P3 V.5: PN2 Experiment 1 12 NC1850 .P28 P3 V.6: PN2 Experiment 1 13 NC1850 .P28 P3 V.7: PN2 Experiment 1 14 NC1850 .P28 P3 V.9: PN2 Experiment 1 15 NC1850 .P28 P3 V.10: PN2 Experiment 1 16 NC1850 .P28 P3 V.12: PN2 Experiment 1 17 NC1850 .P28 P3 V.13: PN2 Experiment 1 18 NC1860 .N4: Peace Post Card no. -

Addison Street Poetry Walk

THE ADDISON STREET ANTHOLOGY BERKELEY'S POETRY WALK EDITED BY ROBERT HASS AND JESSICA FISHER HEYDAY BOOKS BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA CONTENTS Acknowledgments xi Introduction I NORTH SIDE of ADDISON STREET, from SHATTUCK to MILVIA Untitled, Ohlone song 18 Untitled, Yana song 20 Untitied, anonymous Chinese immigrant 22 Copa de oro (The California Poppy), Ina Coolbrith 24 Triolet, Jack London 26 The Black Vulture, George Sterling 28 Carmel Point, Robinson Jeffers 30 Lovers, Witter Bynner 32 Drinking Alone with the Moon, Li Po, translated by Witter Bynner and Kiang Kang-hu 34 Time Out, Genevieve Taggard 36 Moment, Hildegarde Flanner 38 Andree Rexroth, Kenneth Rexroth 40 Summer, the Sacramento, Muriel Rukeyser 42 Reason, Josephine Miles 44 There Are Many Pathways to the Garden, Philip Lamantia 46 Winter Ploughing, William Everson 48 The Structure of Rime II, Robert Duncan 50 A Textbook of Poetry, 21, Jack Spicer 52 Cups #5, Robin Blaser 54 Pre-Teen Trot, Helen Adam , 56 A Strange New Cottage in Berkeley, Allen Ginsberg 58 The Plum Blossom Poem, Gary Snyder 60 Song, Michael McClure 62 Parachutes, My Love, Could Carry Us Higher, Barbara Guest 64 from Cold Mountain Poems, Han Shan, translated by Gary Snyder 66 Untitled, Larry Eigner 68 from Notebook, Denise Levertov 70 Untitied, Osip Mandelstam, translated by Robert Tracy 72 Dying In, Peter Dale Scott 74 The Night Piece, Thorn Gunn 76 from The Tempest, William Shakespeare 78 Prologue to Epicoene, Ben Jonson 80 from Our Town, Thornton Wilder 82 Epilogue to The Good Woman of Szechwan, Bertolt Brecht, translated by Eric Bentley 84 from For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide I When the Rainbow Is Enuf, Ntozake Shange 86 from Hydriotaphia, Tony Kushner 88 Spring Harvest of Snow Peas, Maxine Hong Kingston 90 Untitled, Sappho, translated by Jim Powell 92 The Child on the Shore, Ursula K. -

Elinor Morton Wylie - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Elinor Morton Wylie - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Elinor Morton Wylie(7 September 1885 – 16 December 1928) Elinor Wylie was an American poet and novelist popular in the 1920s and 1930s. "She was famous during her life almost as much for her ethereal beauty and personality as for her melodious, sensuous poetry." <b>Family and Childhood</b> Elinor Wylie was born Elinor Morton Hoyt in Somerville, New Jersey, into a socially prominent family. Her grandfather, Henry M. Hoyt, was a governor of Pennsylvania. Her aunt was Helen Hoyt, a minor poet. Her parents were Henry Martyn Hoyt, Jr., who would be United States Solicitor General from 1903 to 1909; and Anne Morton McMichael (born July 31, 1861 in Pa.). Their other children were: Henry Martyn Hoyt (May 8, 1887 in Pa. – 1920 in New York City) who married Alice Gordon Parker (1885–1951) Constance A. Hoyt (May 20, 1889 in Pa. – 1923 in Bavaria, Germany) who married Ferdinand von Stumm-Halberg on March 30, 1910 in Washington, D.C. Morton McMichael Hoyt (born April 4, 1899 in Washington, D.C.), three times married and divorced Eugenia Bankhead, known as "Sister" and sister of Tallulah Bankhead Nancy McMichael Hoyt (born October 1, 1902 in Washington, D.C) romance novelist who wrote Elinor Wylie: The Portrait of an Unknown Woman (1935). She married Edward Davison Curtis; they divorced in 1932. Elinor was educated at Miss Baldwin's School (1893–97), Mrs. Flint's School (1897–1901), and finally Holton-Arms School (1901–04). -

Jack Spicer Papers, 1939-1982, Bulk 1943-1965

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt9199r33h No online items Finding Aid to the Jack Spicer Papers, 1939-1982, bulk 1943-1965 Finding Aid written by Kevin Killian The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ © 2007 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the Jack Spicer BANC MSS 2004/209 1 Papers, 1939-1982, bulk 1943-1965 Finding Aid to the Jack Spicer Papers, 1939-1982, bulk 1943-1965 Collection Number: BANC MSS 2004/209 The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California Finding Aid Written By: Kevin Killian Date Completed: February 2007 © 2007 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: Jack Spicer papers Date (inclusive): 1939-1982, Date (bulk): bulk 1943-1965 Collection Number: BANC MSS 2004/209 Creator : Spicer, Jack Extent: Number of containers: 32 boxes, 1 oversize boxLinear feet: 12.8 linear ft. Repository: The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California 94720-6000 Abstract: The Jack Spicer Papers, 1939-1982, document Spicer's career as a poet in the San Francisco Bay Area. Included are writings, correspondence, teaching materials, school work, personal papers, and materials relating to the literary magazine J. Spicer's creative works constitute the bulk of the collection and include poetry, plays, essays, short stories, and a novel. Correspondence is also significant, and includes both outgoing and incoming letters to writers such as Robin Blaser, Harold and Dora Dull, Robert Duncan, Lewis Ellingham, Landis Everson, Fran Herndon, Graham Mackintosh, and John Allan Ryan, among others. -

List of Poems Used in Literary Criticism Contests, 2009

UIL Literary Criticism Poetry Selections 2021 William Wordsworth's "Strange Fits of Passion Have I Known" Percy Bysshe Shelley "To Wordsworth" Mark Hoult's clerihew "[Edmund Clerihew Bentley]" unattributed clerihew "[Lady Gaga—]" 2021 A 2021 Richard Wilbur's "The Catch" William Wordsworth's "[Most sweet it is with unuplifted eyes]" William Wordsworth's "She Dwelt among Untrodden Ways" Marge Piercy's "What's That Smell in the Kitchen?" Robert Browning's "Meeting at Night" Donald Justice's "Sonnet: The Poet at Seven" 2021 B 2021 William Wordsworth's "To Sleep" William Wordsworth's "Lucy Gray" William Wordsworth's "The Solitary Reaper" Richard Wilbur's "Boy at the Window" Alfred, Lord Tennyson's "Tears, Idle Tears" 2021 D 2021 Christina Rossetti's "Sleeping at Last" William Wordsworth's "[My heart leaps up when I behold]" William Wordsworth's "I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud" William Wordsworth's "The World Is Too Much with Us" John Keats's "On Seeing the Elgin Marbles" Anthony Hecht's "The End of the Weekend" 2021 R 2021 Elizabeth Bishop's "Little Exercise" Billy Collins's "Dharma" William Wordsworth's "Expostulation and Reply" William Wordsworth's "Matthew" Charles Lamb's "The Old Familiar Faces" Louis Untermeyer's "The Victory of the Beet-Fields" 2021 S 2021 Ralph Waldo Emerson's "Bramha" Elinor Wylie's "Pretty Words" italics indicate that the poem is found in Part 4 UIL Literary Criticism Poetry Selections 2020 Percy Bysshe Shelley's "Ozymandias" Percy Bysshe Shelley's "Song: To the Men of England" William Shakespeare's Sonnet 73 A Alanis Morissette's "Head over Feet" Mary Holtby's "Milk-cart" Emily Dickinson's "[A Bird came down the Walk]" 2020 Percy Bysshe Shelley's "Ozymandias" and Sheikh Sa'di's "[A Vision of the Sultan Mahmud]" Percy Bysshe Shelley's "England in 1819" Percy Bysshe Shelley's "One word is too often profaned" B William Shakespeare's Sonnet 2 John Updike's "Player Piano" 2020 Thomas Hardy's "Transformations" Percy Bysshe Shelley's "[Tell me thou Star, whose wings of light]" Percy Bysshe Shelley's "To Wordsworth" Percy Bysshe Shelley's "To Jane. -

Published Occasionally by the Friends of the Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley, California 94720

PUBLISHED OCCASIONALLY BY THE FRIENDS OF THE BANCROFT LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA 94720 No. 6l May 197s Dr. and Mrs. David Prescott Barrows, with their children, Anna, Ella, Tom, and Betty, at Manila, ig And it is the story of "along the way" that '111 Along the Way comprises this substantial transcript, a gift from her children in honor of Mrs. Hagar's You Have Fun!" seventy-fifth birthday. In her perceptive introduction to Ella Bar From a childhood spent for the most part rows Hagar's Continuing Memoirs: Family, in the Philippines where her father, David Community, University, Marion Sproul Prescott Barrows, served as General Super Goodin notes that the last sentence of this intendent of Education, Ella Barrows came interview, recently completed by Bancroft's to Berkeley in 1910, attended McKinley Regional Oral History Office, ends with the School and Berkeley High School, and en phrase: "all along the way you have fun!" tered the University with its Class of 1919. [1] Life in the small college town in those halcy Annual Meeting: June 1st Bancroft's Contemporary on days before the first World War is vividly recalled, and contrasted with the changes The twenty-eighth Annual Meeting of Poetry Collection brought about by the war and by her father's The Friends of The Bancroft Library will be appointment to the presidency of the Uni held in Wheeler Auditorium on Sunday IN THE SUMMER OF 1965 the University of versity in December, 1919. From her job as afternoon, June 1st, at 2:30 p.m. -

Elinor Wylie (1885-1928), Studio Portrait, Ca. 1914, by Debenham

Eli nor Wyli e (1 885-1928), studio portrait, ca. 19 14, by D ebenham and Gould Studio, Bourn emouth, England. Courtesy ofthe Berg Collection, New York Public l ibrary 28 Elinor Wylie's Mount Desert Island Retreat Car/Little The Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (1 792-1822) once voiced a desire to withdraw from the world with two yo ung girls, four or five years old, whom he would watch over as if he were their fa ther. In some sequestered spot, he would direct their education and observe the "impress ions of the world . upon the mind when it has been ve iled from human prejudice." 1 It was Elinor Wylie (1885-1 928), accl aimed writer and an authori ty on Shelley's life and writings, who conducted the poet's unusual social experiment in a short story published in the September 1927 issue of Harper 's Bazaar.2 The "seques tered spot" she chose fo r the poet and his pupils? Bar Island in the mouth of Somes H arbor. Wylie's fa nciful tale, titled ''A Birthday Cake for Lionel," opens this way: "It was the fo urth of August in the year 1832, and upon the ro und piney islet whi ch li es at the head of Somes' So und two little girls were engaged in icing a birthday cake."3 Artemis and Jezebel are making the cake fo r fo rty-year-old Li onel Anon, aka Percy Bysshe Shelley, who is away that day "fi shing the deep waters pas t Little C ranberry"-a long row even for the most hale of Romantic poets. -

Reflections on Poetry & Social Class

The Stamp of Class: Reflections on Poetry and Social Class Gary Lenhart http://www.press.umich.edu/titleDetailLookInside.do?id=104886 The University of Michigan Press, 2005. Opening the Field The New American Poetry By the time that Melvin B. Tolson was composing Libretto for the Republic of Liberia, a group of younger poets had already dis- missed the formalism of Eliot and his New Critic followers as old hat. Their “new” position was much closer to that of Langston Hughes and others whom Tolson perceived as out- moded, that is, having yet to learn—or advance—the lessons of Eliotic modernism. Inspired by action painting and bebop, these younger poets valued spontaneity, movement, and authentic expression. Though New Critics ruled the established maga- zines and publishing houses, this new audience was looking for something different, something having as much to do with free- dom as form, and ‹nding it in obscure magazines and readings in bars and coffeehouses. In 1960, many of these poets were pub- lished by a commercial press for the ‹rst time when their poems were gathered in The New American Poetry, 1946–1960. Editor Donald Allen claimed for its contributors “one common charac- teristic: total rejection of all those qualities typical of academic verse.” The extravagance of that “total” characterizes the hyperbolic gestures of that dawn of the atomic age. But what precisely were these poets rejecting? Referring to Elgar’s “Enigma” Variations, 85 The Stamp of Class: Reflections on Poetry and Social Class Gary Lenhart http://www.press.umich.edu/titleDetailLookInside.do?id=104886 The University of Michigan Press, 2005. -

James S. Jaffe Rare Books Llc

JAMES S. JAFFE RARE BOOKS LLC ARCHIVES & COLLECTIONS / RECENT ACQUISITIONS 15 Academy Street P. O. Box 668 Salisbury, CT 06068 Tel: 212-988-8042 Email: [email protected] Website: www.jamesjaffe.com Member Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America / International League of Antiquarian Booksellers All items are offered subject to prior sale. Libraries will be billed to suit their budgets. Digital images are available upon request. 1. [ANTHOLOGY] CUNARD, Nancy, compiler & contributor. Negro Anthology. 4to, illustrations, fold-out map, original brown linen over beveled boards, lettered and stamped in red, top edge stained brown. London: Published by Nancy Cunard at Wishart & Co, 1934. First edition, first issue binding, of this landmark anthology. Nancy Cunard, an independently wealthy English heiress, edited Negro Anthology with her African-American lover, Henry Crowder, to whom she dedicated the anthology, and published it at her own expense in an edition of 1000 copies. Cunard’s seminal compendium of prose, poetry, and musical scores chiefly reflecting the black experience in the United States was a socially and politically radical expression of Cunard’s passionate activism, her devotion to civil rights and her vehement anti-fascism, which, not surprisingly given the times in which she lived, contributed to a communist bias that troubles some critics of Cunard and her anthology. Cunard’s account of the trial of the Scottsboro Boys, published in 1932, provoked racist hate mail, some of which she published in the anthology. Among the 150 writers who contributed approximately 250 articles are W. E. B. Du Bois, Arna Bontemps, Sterling Brown, Countee Cullen, Alain Locke, Arthur Schomburg, Samuel Beckett, who translated a number of essays by French writers; Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, William Carlos Williams, Louis Zukofsky, George Antheil, Ezra Pound, Theodore Dreiser, among many others. -

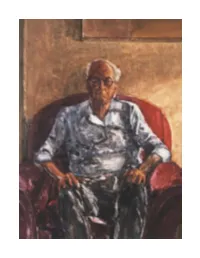

William Bronk

Neither Us nor Them: Poetry Anthologies, Canon Building and the Silencing of William Bronk David Clippinger Argotist Ebooks 2 * Cover image by Daniel Leary Copyright © David Clippinger 2012 All rights reserved Argotist Ebooks * Bill in a Red Chair, monotype, 20” x 16” © Daniel Leary 1997 3 The surest, and often the only, way by which a crowd can preserve itself lies in the existence of a second crowd to which it is related. Whether the two crowds confront each other as rivals in a game, or as a serious threat to each other, the sight, or simply the powerful image of the second crowd, prevents the disintegration of the first. As long as all eyes are turned in the direction of the eyes opposite, knee will stand locked by knee; as long as all ears are listening for the expected shout from the other side, arms will move to a common rhythm. (Elias Canetti, Crowds and Power) 4 Neither Us nor Them: Poetry Anthologies, Canon Building and the Silencing of William Bronk 5 Part I “So Large in His Singleness” By 1960 William Bronk had published a collection, Light and Dark (1956), and his poems had appeared in The New Yorker, Poetry, Origin, and Black Mountain Review. More, Bronk had earned the admiration of George Oppen and Charles Olson, as well as Cid Corman, editor of Origin, James Weil, editor of Elizabeth Press, and Robert Creeley. But given the rendering of the late 1950s and early 1960s poetry scene as crystallized by literary history, Bronk seems to be wholly absent—a veritable lacuna in the annals of poetry. -

View Prospectus

Archive from “A Secret Location” Small Press / Mimeograph Revolution, 1940s–1970s We are pleased to offer for sale a captivating and important research collection of little magazines and other printed materials that represent, chronicle, and document the proliferation of avant-garde, underground small press publications from the forties to the seventies. The starting point for this collection, “A Secret Location on the Lower East Side,” is the acclaimed New York Public Library exhibition and catalog from 1998, curated by Steve Clay and Rodney Phillips, which documented a period of intense innovation and experimentation in American writing and literary publishing by exploring the small press and mimeograph revolutions. The present collection came into being after the owner “became obsessed with the secretive nature of the works contained in the exhibition’s catalog.” Using the book as a guide, he assembled a singular library that contains many of the rare and fragile little magazines featured in the NYPL exhibition while adding important ancillary material, much of it from a West Coast perspective. Left to right: Bill Margolis, Eileen Kaufman, Bob Kaufman, and unidentified man printing the first issue of Beatitude. [Ref SL p. 81]. George Herms letter ca. late 90s relating to collecting and archiving magazines and documents from the period of the Mimeograph Revolution. Small press publications from the forties through the seventies have increasingly captured the interest of scholars, archivists, curators, poets and collectors over the past two decades. They provide bedrock primary source information for research, analysis, and exhibition and reveal little known aspects of recent cultural activity. The Archive from “A Secret Location” was collected by a reclusive New Jersey inventor and offers a rare glimpse into the diversity of poetic doings and material production that is the Small Press Revolution.