The Modernization of Judaism According to the Teachings of Rabbi A.I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evreiskiye Uroki: Resources, Contacts, and Strategies in Jewish Education for Russian-Speaking Jews

Evreiskiye Uroki: Resources, Contacts, and Strategies in Jewish Education for Russian-Speaking Jews October 2003 UJA-Federation Leadership President Secretary Larry Zicklin* Esther Treitel Chair of the Board Executive Committee at Large Morris W. Offit* Froma Benerofe* Roger W. Einiger* Executive Vice President & CEO Matthew J. Maryles* John S. Ruskay Merryl Tisch* Chair, Caring Commission Marc A. Utay* Cheryl Fishbein* Erika Witover* Roy Zuckerberg* Chair Commission on Jewish Identity and Renewal Vice President for Strategic Planning Scott A. Shay* and Organizational Resources Alisa Rubin Kurshan Chair, Commission on the Jewish People Liz Jaffe* Vice President for Agency and External Relations Chair Louise B. Greilsheimer Jewish Communal Network Commission Stephen R. Reiner* Senior Vice President Paul M. Kane General Campaign Chair Jerry W. Levin* Chief Financial Officer Irvin A. Rosenthal Campaign Chairs Philip Altheim Executive Vice Presidents Emeriti Marion Blumenthal* Ernest W. Michel Philip L. Milstein Stephen D. Solender Daniel S. Och Managing Director of the Commission on Jodi J. Schwartz Jewish Identity and Renewal Lynn Tobias* Rabbi Deborah Joselow Treasurer *Executive Committee member Paul J. Konigsberg* EVREISKIYE UROKI: RESOURCES, CONTACTS, AND STRATEGIES IN JEWISH EDUCATION FOR RUSSIAN-SPEAKING JEWS ABBY KNOPP AND NADYA STRIZHEVSKAYA THE COMMISSION ON JEWISH IDENTITY AND RENEWAL UJA-FEDERATION OF NEW YORK 2003 Table of Contents Introduction __________________________________________________________ 1 A Brief Survey of Jewish -

Privatizing Religion: the Transformation of Israel's

Privatizing religion: The transformation of Israel’s Religious- Zionist community BY Yair ETTINGER The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. This paper is part of a series on Imagining Israel’s Future, made possible by support from the Morningstar Philanthropic Fund. The views expressed in this report are those of its author and do not represent the views of the Morningstar Philanthropic Fund, their officers, or employees. Copyright © 2017 Brookings Institution 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, D.C. 20036 U.S.A. www.brookings.edu Table of Contents 1 The Author 2 Acknowlegements 3 Introduction 4 The Religious Zionist tribe 5 Bennett, the Jewish Home, and religious privatization 7 New disputes 10 Implications 12 Conclusion: The Bennett era 14 The Center for Middle East Policy 1 | Privatizing religion: The transformation of Israel’s Religious-Zionist community The Author air Ettinger has served as a journalist with Haaretz since 1997. His work primarily fo- cuses on the internal dynamics and process- Yes within Haredi communities. Previously, he cov- ered issues relating to Palestinian citizens of Israel and was a foreign affairs correspondent in Paris. Et- tinger studied Middle Eastern affairs at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and is currently writing a book on Jewish Modern Orthodoxy. -

Special Lecture by Dr. Marc Shapiro,New

The Nazir in New York ב”ה The Nazir in New York Josh Rosenfeld I. Mishnat ha-Nazir הוצאת נזר דוד שע”י מכון אריאל ירושלים, 2005 קכ’36+ עמודים הראל כהן וידידיה כהן, עורכים A few years ago, during his daily shiur, R. Herschel Schachter related that he and his wife had met someone called ‘the Nazir’ during a trip to Israel. R. Schachter quoted the Nazir’s regarding the difficulty Moshe had with the division of the land in the matter the daughters of Zelophehad and the Talmudic assertion (Baba Batra 158b) that “the air of the Land of Israel enlightens”. Although the gist of the connection I have by now unfortunately forgotten, what I do remember is R. Schachter citing the hiddush of a modern-day Nazir, and how much of a curio it was at the time. ‘The Nazir’, or R. David Cohen (1887-1972) probably would have been quite satisfied with that. Towards the end of Mishnat ha-Nazir (Jerusalem, 2005) – to my knowledge, the most extensive excerpting of the Nazir’s diaries since the the three-volume gedenkschrift Nezir Ehav (Jerusalem, 1978), and the selections printed in Prof. Dov Schwartz’ “Religious Zionism: Between Messianism and Rationalism” (Tel Aviv, 1999) – we see the Nazir himself fully conscious of the hiddush :(עמ’ ע) of his personal status נזיר הנני, שם זה הנני נושא בהדר קודש. אלמלא לא באתי אלא בשביל זה, לפרסם שם זה, להיות בלבות זרע קודש ישראל, צעירי הצאן, זכרונות קודשי עברם הגדול, בגילוי שכינה, טהרה וקדושה, להכות בלבם הרך גלי געגועים לעבר זה שיקום ויהיה לעתיד, חידוש ימינו כקדם, גם בשביל זה כדאי לשאת ולסבול and :(זכרונות מבית אבא מארי ,similarly (p. -

In Dedication of Mr

Weekly Internet Parsha Sheet Re'eh 5777 [See end re eclipse] Rabbi Wein’s Weekly Blog People, who make poor choices, do so on the basis of emotion, desire, PEOPLE foolishness and illusory hopes and false ideas. These are the products Standing on the corner of two major thoroughfares in midtown Manhattan of distorted vision - the inability to see things clearly. Only clear recently I was struck by the number and variety of people walking past. There vision can lead to wise and correct choices. The commandments that were hordes of them all purposefully heading towards some appointed place and event. They were a composite of all of humanity, representing every color the Torah enjoins us to observe are a form of corrective lenses to aid of human skin, babel of languages, all social strata, faiths and ethnic origins. us in seeing things clearly and accurately. When I was a blasé New Yorker twenty-three years ago I never noticed that all People have to pass an eye and vision test in order to be able to legally of these people existed and were parading before me. The anonymity of urban operate an automobile. How much more so is an eye and vision test life allows one to ignore people as though they do not exist. We tend to see necessary when life and death itself is in question? The Torah advises only what we wish to see, the people we can recognize and with whom we can us to always choose life. This is the basis for all Jewish society identify, and we are oblivious to everyone else. -

Sunday, May 24Th 2020

Rabbi David Stav Yeshivat Hakotel Presents Be Inspired for Shavuos and Matan Torah An Unprecedented Worldwide Achdus Learning Experience The World’s Leading Rabbonim, Educators, and Speakers ראש חודש יו, תש“ - SUNDAY, MAY 24TH 2020 US CENTRAL: 9:00 am - 1:30 pm US WEST: 7:00 am - 11:30 am US EAST: 10:00 am - 2:30 pm / / UK: 3:00pm - 7:30 pm / ISRAEL: 5:00 pm - 9:30 pm Chief Rabbis Chief Rabbi Shlomo Amar Chief Rabbi Yisrael Meir Lau Chief Rabbi David Lau Chief Rabbi Yitzchak Yosef Chief Rabbi Warren Goldstein, South Africa Chief Rabbi Ephraim Mirvis, UK Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, UK Senior Roshei Yeshiva Rav Yaakov Bender, Yeshiva Darchei Torah Rav Yisroel Reisman, Torah Voda'as Rav Yitzchak Berkovits, Aish Hatorah Rav Hershel Schachter, RIETS Rav Reuven Feinstein, Yeshiva of Staten Island Rav Asher Weiss, Minchas Asher Rav Avigdor Nevenzahl, Yeshivat Hakotel Rav Baruch Wieder, Yeshivat Hakotel Distinguished Speakers Rebbetzin Aviva Feiner Rav David Aaron Rav YY Jacobson Rav Michael Rosensweig Rebbetzin Tziporah Gottlieb (Heller) Rav Elimelech Biderman Rav Zev Leff Rav YY Rubinstein Mrs. Michal Horowitz Rav Mendel Blachman Rav Aryeh Lebowitz Rav Jacob J. Schacter Mrs. Chani Juravel Rav Yitzchak Breitowitz Rav Menachem Leibtag Rav Ben Zion Shafier Mrs. Yael Kaisman Rav Steven Burg Rav Aharon Lopiansky Rav Efraim Shapiro Mrs. Miriam Kosman Rav Dovid Cohen Rav Eli Mansour Rav Moshe Taragin Rebbetzin Lauren Levin Rav Eytan Feiner Rav Judah Mischel Rav Reuven Taragin Mrs. Sivan Rahav Meir Rav Dovid Fohrman Rav Shraga Neuberger Rav Hanoch Teller Rabbanit Yemima Mizrachi Rav Yoel Gold Rav Noach Isaac Oelbaum Rav Dr. -

Th-12Th Century Spain), Zion Halo Tishali

Zionism, A-Zionism and Anti-Zionism, Week 1 R’ Mordechai Torczyner – [email protected] 1. Israel’s Scroll of Independence The State of Israel will be open to Jewish immigration and the ingathering of the exiles, working toward development of the land for the benefit of all of its inhabitants. It will be founded upon the principles of freedom, justice and peace, by the light of the visions of the prophets of Israel. It will maintain full, equal social and political rights for all her citizens, without distinction based on religion, race or sex. It will guarantee freedom of religion, conscience, language, education and culture. It will guard the sacred places of all religions…. Religious Zionism לו .Rabbi Yitzhak Reines (19th century Lithuania), Or Chadash al Zion, pg .2 It was already envisioned regarding us from the start that the result of the pursuits and oppressions Israel would bear in its exile would be an improvement in its moral state. We now see that these pursuits have awakened and continue to awaken the Zionist ideal, at the least distancing the nation from assimilation, returning to the moral good. Thus there is no doubt that this Zionist movement is that which they prophesied from the start. 3. Deuteronomy 11:17-18 …And Gd will close the heavens and there will be no rain, and the land will not give its produce, and you will quickly be lost from upon the good land Gd is giving you. And you shall place these words upon your hearts and souls … 4. Midrash, Sifri Devarim 43 "And you will quickly be lost… and you shall place these words" – Even though I exile you from the land, be marked by your mitzvot, so that when you return they will not be new for you. -

Influential Ultra-Orthodox Women Are Change Agents for Peace

The ultra-Orthodox women visit the Rabin Center and look at a wall with graffiti that was done by youth the week after the assassination of Prime Minister Rabin. Photo credit: Base for Discussion (B4D) Peacebuilding in practice #1 Influential ultra-Orthodox women are change agents for peace Interpeace’s engagement with ultra-Orthodox women aims to promote the emergence of a new women leadership that is representative of the ultra-Orthodox population in Israel and at the same time committed to dialogue and peace. Influential ultra-Orthodox women are change agents for peace All Rights Reserved, Interpeace, 2014 The ideas, reflexions, and commentaries contained herein are the exclusive responsibility of Interpeace. To- tal or partial reproduction is authorized provided attribution to the source document is properly acknowl- edged. The ultra-Orthodox women visit the Rabbin Center and meet with Rabin’s daughter, Dalia Rabin, who is pictured fourth from right. Photo credit: Base for Discussion (B4D) Peacebuilding in practice #1: Influential ultra-Orthodox women are change agents for peace Background Up until now high-level peace negotiations between Israel and Palestine have lacked broad-based public participation. Without that support, all outcomes from the negotiation table are at much higher risk of failure. Within Israel, there are key sectors of the population that have not been involved in peace initiatives, but who have an influence on the peace process. Most peace initiatives have focused on those in Israel who are already part of the peace camp. If a future accord is to bring lasting peace, it is essential that sidelined groups are brought into the peace process, especially as there will potentially be a referendum on the subject. -

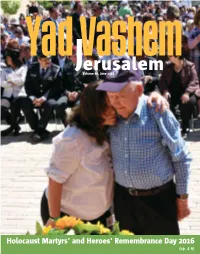

Jerusalemhem Volume 80, June 2016

Yad VaJerusalemhem Volume 80, June 2016 Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Day 2016 (pp. 4-9) Yad VaJerusalemhem Contents Volume 80, Sivan 5776, June 2016 Inauguration of the Moshe Mirilashvili Center for Research on the Holocaust in the Soviet Union ■ 2-3 Published by: Highlights of Holocaust Remembrance Day 2016 ■ 4-5 Students Mark Holocaust Remembrance Day Through Song, Film and Creativity ■ 6-7 Leah Goldstein ■ Remembrance Day Programs for Israel’s Chairman of the Council: Rabbi Israel Meir Lau Security Forces ■ 7 Vice Chairmen of the Council: ■ On 9 May 2016, Yad Vashem inaugurated Dr. Yitzhak Arad Torchlighters 2016 ■ 8-9 Dr. Moshe Kantor the Moshe Mirilashvili Center for Research on ■ 9 Prof. Elie Wiesel “Whoever Saves One Life…” the Holocaust in the Soviet Union, under the Chairman of the Directorate: Avner Shalev Education ■ 10-13 auspices of its world-renowned International Director General: Dorit Novak Asper International Holocaust Institute for Holocaust Research. Head of the International Institute for Holocaust Studies Program Forges Ahead ■ 10-11 The Center was endowed by Michael and Research and Incumbent, John Najmann Chair Laura Mirilashvili in memory of Michael’s News from the Virtual School ■ 10 for Holocaust Studies: Prof. Dan Michman father Moshe z"l. Alongside Michael and Laura Chief Historian: Prof. Dina Porat Furthering Holocaust Education in Germany ■ 11 Miriliashvili and their family, honored guests Academic Advisor: Graduate Spotlight ■ 12 at the dedication ceremony included Yuli (Yoel) Prof. Yehuda Bauer Imogen Dalziel, UK Edelstein, Speaker of the Knesset; Zeev Elkin, Members of the Yad Vashem Directorate: Minister of Immigration and Absorption and Yossi Ahimeir, Daniel Atar, Michal Cohen, “Beyond the Seen” ■ 12 Matityahu Drobles, Abraham Duvdevani, New Multilingual Poster Kit Minister of Jerusalem Affairs and Heritage; Avner Prof. -

Publications

Publications: Monographs: The Ultraorthodox Jews in Israel at the 21st Century, Berlin 2021 (in print). [in German] Exile or Home? The Immigration and Integration of Polish Jews from 1968 into Israel: a qualitative case study based on interview analysis, Potsdam 2014. [in German] Documentary Movie: „There is No Return to Egypt“. Polish Jews from 1968 in Israel today, 45mins, Potsdam, 2014. [in Polish and Hebrew with German and English subtitles] Link: https://web.ub.uni-potsdam.de/php/show_multimediafile.php?mediafile_id=508 Papers (selection): „Grandpa, next month I’ll move to Berlin“. The Return of Israeli Jews to Germany in Israeli Documentary Films in the 21st Century, in: Doron Kiesel and Lea Wohl (eds.), Ambivalences. Jewish Filmmakers and their Relationship to Germany, Berlin 2020 (in print). [in German] „Entre Aversion et nostalgie. Immigration et intégration des Juifs polonais de 1968 en Israel – analyse d’interviews et documentation filmée“, Bulletin du Centre de recherche fran recherche français à Jérusalem, 22, 2013. „The 1968 Immigrants from Poland in Israel. A documentary film by Eik Dödtmann and Klemens Czyzydlo”, in: Israel and Poland in 1945-2005. Selected Aspects of Jewish Life in Both Countries, Kraków, pp. 43-53. Selected journalistic articles, book reviews, interviews [originals in German]: “In the Name of Zionism. How Jewish Immigrants change their Names into Hebrew because of Ideology, to have better Career Chances or in Fear of Discrimination”, Jüdische Zeitung, July 2014. “«They are there, we are here». Shalom Cohen is the new spiritual leader of the Sephardic- religious Party Shass“, Jüdische Zeitung, June 2014. “In the Future even more rightwing? A recent survey shows that the majority of Israelis in the Age between 15 to 18 support rightwing parties”, Jüdische Zeitung, May 2014. -

The Conversion Crisis: Preserving the Jewish Character Of

Israel The The Conversion New Crisis: Preserving the Israelis Jewish Character of the Jewish State: By Jonathan Rosenblum he founders of the State of Israel understood that in order In a May 16, 2003, interview with The Jerusalem Post, That vision is a dangerous one. One may speak of a million T to preserve its authentic Jewish character and maintain the unity of Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon admitted that one of the new immigrants from the former Soviet Union, as Sharon the people, personal status had to be determined by the Chief Rabbinate. reasons for his decision to leave Likud’s traditional Chareidi does, or one may pay obeisance to the idea of a Jewish state However, at the present time, the so-called status quo is under attack allies out of his government coalition was his desire to bring (however defined), but it is pure cynicism to claim to favor from all sides, and concomitantly, national unity is seriously threatened. another one million immigrants from the former Soviet both. Fast-track conversion does not provide the magic means The last tidal wave of Russian immigration and the miniscule Union to Israel. “Without the Chareidim in key positions for reconciling these antagonistic goals and can only bring a dictating policy on this issue, there is a chance for greater number of negative consequences in its wake. immigration of the Bnei Menashe provide two quite different exam- immigration,” said the prime minister. ples of absorption into Israeli society. The Bnei Menashe allege to be Two months later, in response to Absorption Minister A Million New IsraelisÑA Mixed Blessing descendants of the tribe of Menashe and are sincerely interested in Tzippi Livni’s statement that more “Jews” emigrated from the leading observant Jewish lives. -

The Search for a Spiritual Revival of Judaism Among Russian Jews

Machanaim: The Search for a Spiritual Revival of Judaism among Russian Jews Byline: Kitrossky, Kara-Ivanov and Polonsky After the Six Day War there was a considerable renewal of interest in Israel throughout the world. At the same time, a Jewish national revival began in the USSR. Jewish identity started to acquire a new shape. Soviet Jews always had a distinct identity, but in many cases it was a "negative" one, caused by discrimination and persecution. Many people started investigating their Jewishness, learning Hebrew and thinking about going to Israel. But still more primary was the total rejection of the Soviet system, its regime, ideology, and values. This resulted in many Jews wanting to leave the USSR. By 1980 many Jews had applied for emigration from the USSR. The official destination was Israel, but a majority used their exit visas to go to the USA. In the seventies many people were able to emigrate, but some were refused permission to leave, and the Refusenik phenomenon was created. After the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 Jewish emigration practically stopped. Refuseniks and people planning eventually to leave the USSR were already far detached from Soviet ideology or had never been adherents of it. Refuseniks' Jewish national consciousness was developed to some extent. But they were trapped in a cold winter of the late days of failing Communism. Some of them became Zionists; others joined the struggle for human rights (the dissident movement), some tried to study Jewish culture, primarily Hebrew. Studying Jewish culture and traditions led some people to the Jewish religion. -

Israel's Chief Rabbinate, the Conversion Crisis, and Halakhic Chaos

Israel's Chief Rabbinate, the Conversion Crisis, and Halakhic Chaos These articles by Isi Leibler originally appeared in the Jerusalem Post and Yisrael Hayom. The tensions created by the ultra-Orthodox Chief Rabbinate within Israeli society have extended to the Diaspora and are now undermining relations with the Jewish state. Ironically, this is taking place at a time when many Israelis are returning to their spiritual roots. Although Tel Aviv remains outwardly a hedonistic secular city, the secular Ashkenazi outlook that dominated Israeli society is in decline, and even setting aside haredim, Israelis today have become increasingly more traditionally inclined and religiously observant. The past decades have witnessed the emergence of observant Jews at all senior levels of society. There has been a dramatic revolution in the Israel Defense Forces with national-religious soldiers now occupying senior positions, assuming roles in combat units parallel to what their kibbutz predecessors did in the early years of statehood. There is even a thirst for spiritual values among secular Israelis, accompanied by a major revival of the study of Jewish texts. Yet simultaneously, there is revulsion and rage at the corruption, extortion and political leverage imposed by powerful haredi political parties and their rabbis. Unfortunately, the ultra-Orthodox rabbis have effectively exploited their political leverage to assume control of the Chief Rabbinate, which, ironically, they themselves have always despised. Current Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi David Lau and his Sephardi counterpart, Chief Rabbi Yitzhak Yosef, represent the antithesis of the Chief Rabbinate created 90 years ago by Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, who strove to unite the nation.