The Case of Preparation for the Pyeongchang Olympics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Levi, Finland on 14 Th November 2008

1 To the • National Ski Associations • Members of the FIS Council • Committee Chairmen Oberhofen, 19th November 2008 SL/er FIS Council Meeting 14 th November 2008, Levi (FIN) Dear Mr. President, Dear Ski friends, In accordance with art. 32.2 of the FIS Statutes we take pleasure in sending you today A SHORT SUMMARY of the most important decisions of the FIS Council Meeting, 14 th November 2008 in Levi (FIN) 1. Members present The following Council Members were present at the meeting in Levi, Finland on 14 th November 2008: Short Summary of the Agenda FIS Council Meeting, Levi (FIN), 14 th November 2008 2 President Gian Franco Kasper, Vice-Presidents Yoshiro Ito, Bill Marolt, Carl Eric Stålberg, Leonid Tyagachev and Members Jaakko Holkeri, Milan Jirasek, Janez Kocijancic, Sung-Won Lee, Alain Méthiaz, Giovanni Morzenti, Eduardo Roldan, Pablo Rosenkjer, Sverre Seeberg, Patrick Smith, Fritz Wagnerberger, Werner Woerndle and Secretary General Sarah Lewis. 2. Minutes from the Council Meetings in Cape Town (RSA) The minutes from the Council Meetings in Cape Town (RSA) 26th to 29 th May 2008 and the newly elected Council on 31 st May 2008 were approved with minor amendments under Item 14.1.2, Possible Violations of FIS and IOC Anti- Doping Rules during the Olympic Winter Games 2006 in Torino and Item 5 Minutes of the newly-elected FIS Council, Appointment of FIS Committees. 2.1 Matters Arising The Council addressed remarks from Austria, Canada and the USA that were raised in relation to the FIS Medical Rules and Guidelines, notably the FIS Event Organiser Medical Support Requirements for Alpine, Ski Jumping, Snowboard and Freestyle Disciplines. -

Brazil, Japan, and Turkey

BRAZIL | 1 BRAZIL, JAPAN, AND TURKEY With articles by Marcos C. de Azambuja Henri J. Barkey Matake Kamiya Edited By Barry M. Blechman September 2009 2 | AZAMBUJA Copyright ©2009 The Henry L. Stimson Center Cover design by Shawn Woodley Photograph on the front cover from the International Atomic Energy Agency All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written consent from The Henry L. Stimson Center. The Henry L. Stimson Center 1111 19th Street, NW 12th Floor Washington, DC 20036 phone: 202-223-5956 fax: 202-238-9604 www.stimson.org BRAZIL | 3 PREFACE I am pleased to present Brazil, Japan, and Turkey, the sixth in a series of Stimson publications addressing questions of how the elimination of nuclear weapons might be achieved. The Stimson project on nuclear security explores the practical dimensions of this critical 21st century debate, to identify both political and technical obstacles that could block the road to “zero,” and to outline how each of these could be removed. Led by Stimson's co-founder and Distinguished Fellow Dr. Barry Blechman, the project provides useful analyses that can help US and world leaders make the elimination of nuclear weapons a realistic and viable option. The series comprises country assessments, published in a total of six different monographs, and a separate volume on such technical issues as verification and enforcement of a disarmament regime, to be published in the fall. This sixth monograph in the series, following volumes on France and the United Kingdom, China and India, Israel and Pakistan, Iran and North Korea, and Russia and the United States, examines three countries without nuclear weapons of their own, but which are nonetheless key states that would need to be engaged constructively in any serious move toward eliminating nuclear weapons. -

I Love Korea!

I Love Korea! TheThe story story of of why why 33 foreignforeign tourists tourists fellfell in in love love with Korea. Korea. Co-plannedCo-planned by bythe the Visit Visit Korea Korea Committee Committee & & the the Korea Korea JoongAng JoongAng Daily Daily I Love Korea! The story of why 33 foreign tourists fell in love with Korea. Co-planned by the Visit Korea Committee & the Korea JoongAng Daily I Love Korea! This book was co-published by the Visit Korea Committee and the Korea JoongAng Daily newspaper. “The Korea Foreigners Fell in Love With” was a column published from April, 2010 until October, 2012 in the week& section of the Korea JoongAng Daily. Foreigners who visited and saw Korea’s beautiful nature, culture, foods and styles have sent in their experiences with pictures attached. I Love Korea is an honest and heart-warming story of the Korea these people fell in love with. c o n t e n t s 012 Korea 070 Heritage of Korea _ Tradition & History 072 General Yi Sun-sin 016 Nature of Korea _ Mountains, Oceans & Roads General! I get very emotional seeing you standing in the middle of Seoul with a big sword 018 Bicycle Riding in Seoul 076 Panmunjeom & the DMZ The 8 Streams of Seoul, and Chuseok Ah, so heart breaking! 024 Hiking the Baekdudaegan Mountain Range Only a few steps separate the south to the north Yikes! Bang! What?! Hahaha…an unforgettable night 080 Bukchon Hanok Village, Seoul at the Jirisan National Park’s Shelters Jeongdok Public Library, Samcheong Park and the Asian Art Museum, 030 Busan Seoul Bicycle Tour a cluster of -

Asia Lights up Winter Yog

Official Newsletter of the Olympic Council of Asia Edition 48 - March 2020 ASIA LIGHTS UP WINTER YOG GOLD MEDALS GALORE AT LAUSANNE 2020 OCA Games Updates NOC News in Pictures OCA pays tribute to Sultan Qaboos Regional Games Round-up Contents Inside Sporting Asia, Edition 48 – March 2020 Sporting Asia is the official 3 President’s Message newsletter of the Olympic Council of Asia, published quarterly. 4 - 7 News in Pictures 10 Executive Editor / Director General Husain Al-Musallam 8 - 9 Awards [email protected] Director, Int’l & NOC Relations 10 - 13 OCA Games Updates Vinod Tiwari [email protected] 10 - 11 6th Asian Beach Games Sanya 2020 Director, Asian Games Department Haider A. Farman 12 - 13 19th Asian Games Hangzhou 2022 [email protected] 14 Inside the OCA Editor Jeremy Walker 15 [email protected] 15 - 22 Asia at the 3rd Winter Youth Olympic Executive Secretary Games Lausanne 2020 Nayaf Sraj [email protected] NOC Focus: Singapore 23 Olympic Council of Asia PO Box 6706, Hawalli Zip Code 32042 24 - 25 30th Southeast Asian Games Philippines 2019 Kuwait Telephone: +965 22274277 - 88 Fax: +965 22274280 - 90 24 26 - 27 13th South Asian Games Nepal 2019 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ocasia.org 28 - 29 Road to Tokyo 2020 30 - 31 Asia’s Olympic Era 30 Tokyo 2020 28 31 Beijing 2022 32 - 33 Women in Sport Front Cover: Korea’s You Young won the 34 News in Brief ladies’ figure skating gold medal at the Winter Youth Olympic Games Lausanne 35 Obituary: Sultan Qaboos of Oman 2020 and was named No. -

4. the Winter Olympics As a Construction Project

Edinburgh Research Explorer The 2018 Winter Olympic Games in PyeongChang Citation for published version: Lee, J-W 2018, 'The 2018 Winter Olympic Games in PyeongChang: In between a mega sporting event and a mega construction project ', Regeneration, Enterprise, Sport and Tourism , Liverpool, United Kingdom, 20/02/18 - 21/02/18. Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Other version General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 06. Oct. 2021 The 2018 Winter Olympic Games in Pyeongchang: In between a mega sporting event and a mega construction project Dr Jung Woo Lee (Edinburgh Critical Studies in Sport Research Group) OUTLINE 1. The 2018 Pyeongchang Winter Olympics 2. Olympic Agenda 2020 3. The Olympics / Development Industry Complex 4. The Winter Olympics as a Construction Project 5. Who is winning the Games? 6. Implications 1. The 2018 Pyeongchang Winter Olympics A Sporting Spectacle for Two Weeks 16 Years of Preparation: Third Time Lucky? Candidate City for 2010, 2014, and 2018 Winter Olympics 1. -

School Choice Guide 2013-2014

beijingkids edition February 2013 PRICE:RMB¥10.00(DOMESTIC) US$4.95(ABROAD) School Choice Guide 2013-2014 Feature 10 Charting Your Course A guide to education systems in Beijing 24 Moving Towards Independence The ins and outs of middle school prep 28 Internationally-Minded 10 How to approach bilingual education Listings 33 Schools by Alphabetical Order 34 Schools by Area (List) 35 Schools by Education System 36 Schools by Area (Chart) 37 Schools by Age Group 24 38 School Profiles Directories 104 Family Health 105 Family Life 105 Family Travel 107 Fun Stuff 107 Shopping 28 108 Sports ON THE COVER: Calista (age 9) and her brother Ethan Family Focus Shepheard (age 6) are Year 4 and Year 1 students respectively at The British School of Beijing (BSB). Calista’s favorite subjects are PE and music – where she plays the 112 The Carr Family cello. Ethan enjoys recess and his favorite ASA is swimming with BSB’s Splash Club. Photo by Littleones Kids & Family Portrait Studio. A special thanks to The British School of Beijing. 《中国妇女》英文刊 2012 年 2 月(下半月) WOMEN OF CHINA English Monthly WOMEN OF CHINA English Monthly Sponsored and administrated by ALL-CHINA WOMEN’S FEDERATION 中华全国妇女联合会主管/主办 Published by WOMEN’S FOREIGN LANGUAGE PUBLICATIONS OF CHINA 中国妇女外文期刊社出版 Publishing Date: February 1st, 2012 本期出版时间: 2012年2月1日 Adviser 顾 问 彭 云 PENG PEIYUN 中华全国妇女联合会名誉主席 全国人大常委会前副委员长 Honorary President of the ACWF and Former Vice-Chairperson of the NPC Standing Committee Adviser 顾 问 顾秀莲 GU XIULIAN 全国人大常委会前副委员长 Former Vice-Chairperson of the NPC Standing Committee Director -

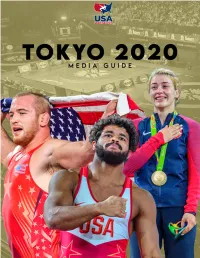

Themat.Com | @Usawrestling | #Tokyo2020 1 Table of Contents

themat.com | @usawrestling | #Tokyo2020 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Info 3 Schedule & press info 4-5 U.S. Team preview Greco-Roman 7 Roster 8 Expected field 9-14 Bios & previews Women’s freestyle 16 Roster 17 Expected field 18-23 Bios & previews Men’s freestyle 25 Roster 26 Expected field 27-32 Bios & previews Coaches 34 Greco-Roman 35 Women’s freestyle 36 Men’s freestyle 2020 USA Wrestling Tokyo Olympics Media Guide Credits Team Leaders 38 Bios The 2020 USA Wrestling Tokyo Olympics media guide was edited and designed by Taylor Miller. Special History thanks to USA Wrestling communications staff Mike 40-44 World and Olympic records Willis and Gary Abbott. Photos by Tony Rotundo. themat.com | @usawrestling | #Tokyo2020 2 SCHEDULE & PRESS iNFO 2020 TOKYO OLYMPIC GAMES USOPC WRESTLING PRESS OFFICERS at Tokyo, Japan (Aug. 1-7, 2021) Gary Abbott Sunday, Aug. 1 Email - [email protected] 11 a.m. – Qualification rounds (GR 60, 130; WFS 76 kg) Phone number - +1 719-659-9637 6:15 p.m. – Semifinals (GR 60, 130; WFS 76 kg) Monday, Aug. 2 11 a.m. – Qualification rounds (GR 77, 97; WFS 68 kg) Taylor Miller 11 a.m. – Repechage (GR 60, 130; WFS 76 kg) Email - [email protected] 6:15 p.m. – Semifinals (GR 77, 97; WFS 68 kg) Phone number - +1 405-420-8622 7:30 p.m. - Finals (GR 60, 130; WFS 76 kg) Tuesday, Aug. 3 11 a.m. – Qualification rounds (GR 67, 87; WFS 62 kg) Updates on the Olympic Wrestling competition will 11 a.m. – Repechage (GR 77, 97; WFS 68 kg) be provided on TeamUSA.org as well as on USA 6:15 p.m. -

New Officiating Standards Here to Stay the 2006-2007-Season Will Be One of the Most Important in Many There Will Always Be Judgment Involved

October 2006 Volume 10 Number 5 Published by the International Ice Hockey Federation Editor-in-Chief Jan-Ake Edvinsson Supervising Editor Kimmo Leinonen Editor Szymon Szemberg Assistant Editor Jenny Wiedeke Photos: JANI RAJAMÄKI “GOTTA LOVE THE NEW GAME, EH, REF?”: Players like Canada’s Sidney Crosby are major beneficiaries of the stricter rule interpretations that were introduced midway through the international 2005-2006 season. And it’s important that the entire hockey community supports the referees (here Peter Jonak, Slovakia) in enforcing the tighter application of the rules, especially on the restraining fouls, holding, hooking and interference. There is no way back, writes IIHF President René Fasel in his editorial. New officiating standards here to stay The 2006-2007-season will be one of the most important in many There will always be judgment involved. The referees are instructed to crack down on years in international hockey. It is the season when the stricter rule fouls that impede a player that has gained a positional advantage over his opponent. enforcement is in place from day one. And there is no going back. They are not instructed to indulge in a fundamentalist interpretation of the rule book. This requires very difficult decision making and a very well-developed feeling for the game and its flow. We don’t want the referees to take over the game and become RENÉ FASEL EDITORIAL stars, what we want is the offensive player skating without being hooked and held. ■■ The Olympic Winter Games in Turin and the IIHF World Championships in Latvia ■■ Through the process, we have noted that the changes are easier to implement in proved that letting the stars shine by getting holding, hooking and interference out of the top hockey nations where, obviously, the general skill level is higher. -

Olympic Family Guide Contents

PyeongChang 2018 Olympic Family Guide Contents 04 Б Welcome Message from the IOC President 05 Б Welcome Message from the POCOG President 07 Б Olympic Winter Games PyeongChang 2018 10 Б Olympic Family Hotels 23 Б Medical Services 26 Б Arrivals & Departures 32 Б Olympic Family Transport Services 55 Б Accreditation 60 Б Ceremonies and Events 63 Б Tickets 67 Б Competition Venues 69 Б Competition Schedule 71 Б Medals Plaza 72 Б Olympic Club 73 Б Olympic Villages 76 Б International Broadcast Centre (IBC) / Main Press Centre (MPC) Complex 78 Б Cultural Programme 80 Б Miscellaneous Information 84 Б Acronyms 85 Б Venue Codes 04 | PyeongChang 2018 Welcome Message from the IOC President Thomas Bach IOC President, Olympic Champion, Fencing, 1976 Dear Friends, Welcome to the Olympic Winter Games PyeongChang 2018! The first Olympic Winter Games in the Republic of Korea will be an amazing experience for everyone. These Games will be inspiring, opening new horizons and bringing the Olympic spirit to a new generation. The Olympic Family Guide offers all the information and practical advice to make your stay in PyeongChang and your Games experience as fulfilling and enjoyable as possible. Our thanks go to the entire team at the Organizing Committee for their effort and commitment to ensuring an extraordinary and memorable event for the athletes, spectators and all the Olympic Family. The Olympic Winter Games PyeongChang 2018 will be a moment for the Olympic spirit to inspire the world. I wish you a wonderful stay in PyeongChang! Olympic Family Guide | 05 Welcome Message from the POCOG President LEE Hee-beom President & CEO of the PyeongChang 2018 Organizing Committee Welcome to Korea. -

Pyeongchang 2018 Paralympic Family Guide Contents

PyeongChang 2018 Paralympic Family Guide Contents 04 • Welcome Message from the IPC President 05 • Welcome Message from the POCOG President 07 • Paralympic Winter Games PyeongChang 2018 10 • Paralympic Family Hotels 15 • Medical Services 19 • Arrivals & Departures 24 • Paralympic Family Transport Services 35 • Accreditation 38 • Opening and Closing Ceremonies 40 • Tickets 45 • Competition Schedule 46 • Competition Venues 48 • Medals Plaza 49 • Paralympic Village 52 • Cultural Programme 55 • International Broadcast Centre (IBC) / Main Press Centre (MPC) Complex 57 • Miscellaneous Information 60 • Acronyms 61 • Venue Codes 04 | PyeongChang 2018 Paralympic Family Guide | 05 Welcome Message Welcome Message from the IPC President from the POCOG President Andrew Parsons LEE Hee-beom IPC President President & CEO of the PyeongChang 2018 Organizing Committee On behalf of the International Paralympic Committee, it is my great pleasure to Welcome to Korea. Welcome to PyeongChang! welcome the whole Paralympic Family to the PyeongChang 2018 Paralympic Winter It is my pleasure to begin by welcoming all Paralympic Family members to the Games. PyeongChang 2018 Paralympic Winter Games. These Games mark the start of three successive editions of the Paralympics that We had a dream. A dream to bring back the enthusiasm of the Paralympic Summer will be held in Asia with Tokyo 2020 and Beijing 2022 already on the horizon. Such a Games Seoul 1988 by hosting the Paralympic Winter Games in Korea. I still vividly platform presents the Paralympic Movement with a unique opportunity to grow in size remember the scene in Durban at the 123rd IOC Session when PyeongChang was and scale in Asia and we will do all we can to take full advantage. -

Itinerary May Delayed Or Changed Depending Weather & Traffic Conditions

High1 MAP North Korea Chorwon Yanggu Panmunjon Chunchon Gangwon-do Gangneung Seoul Vivaldi Park Alpensia Ski Resort Yongpyeong Ski Resort Incheon Pyeongchang Samchok Gyeonggi-do High1 Ski Resort Chingju Chungcheongbuk-do Angdong Chongju Yondok Gyeongsangbuk-do Chungcheongnam-do Sangju Buyeo Daejon Kumchon Puhang Kunsan Daegu Gyeongju Chonju Jeollabuk-do Ulsan Gyeongsangnam-do Jinju Gwangju Masan Busan Jeollanam-do Mokpo Jeju Island Vivaldi Park Yongpyong Alpensia 4 2D1N ALPENSIA RESORT SKI FUN Booking Period: Now - 20 Feb 2019 (Block out Date : 21 - 24, 28 - 31 Dec 2018) Fr.S$278 Travel Period: 01 Dec 2018 - 28 Feb 2019 (Closing date is subjected to the weather condition) Inclusive: (1) 1N stay at Holiday Inn Suites 1 Bedroom Suite (22py) (based on double sharing) (2) 1D Ski Pass at Alpensia Resort (Lift Ticket: Morning + Afternoon) (3) 1D Ski Gear Rental (Ski, Boots and Pole) (4) Round Trip of "Snow Bus Korea" shuttle bus from Seoul Additional Prices in SGD Price in SGD / All prices mentioned is per person basis Items per person 2D1N ALPENSIA RESORT SKI FUN HOLIDAY INN SUITES 4* VALIDITY Adult / Child Ski Clothing Rental S$25 per day Double Extra Person Ski Gloves S$25 per pair 01 Dec 18 - 20 Dec 18 278 208 Goggle S$19 per day SUNDAY-THURSDAY 01 Dec 18 - 20 Dec 18 Helmet S$12 per day 318 208 FRIDAY-SATURDAY Night Ski Pass S$56 21 Dec 18 - 01 Jan 19 408 208 SUNDAY-THURSDAY Night Ski Gear S$25 21 Dec 18 - 01 Jan 19 438 208 Additional 1D Ski Pass 1 Bedroom Suite (22py) FRIDAY-SATURDAY & Rental S$115 (Double/Ondol = Max 3PAX) 02 Jan 19 - 01 Feb 19 *Need to book in advance 358 208 SUNDAY-THURSDAY Private Ski Lesson (2h) S$284 02 Jan 19 - 01 Feb 19 *Max 4 persons 388 208 FRIDAY-SATURDAY 02 Feb 19 - 09 Feb 19 448 208 10 Feb 19 - 28 Feb 19 278 208 SUNDAY-THURSDAY 10 Feb 19 - 28 Feb 19 318 208 FRIDAY-SATURDAY IMPORTANT NOTES ❶Prices are quoted in SGD per person & Subjected to change without prior notice. -

Global Legal Insights: Bribery & Corruption, 8Th Edition – Japan

Bribery & Corruption Eighth Edition Contributing Editors: Jonathan Pickworth & Jo Dimmock Global Legal Insights Bribery & Corruption 2021, Eighth Edition Contributing Editors: Jonathan Pickworth & Jo Dimmock Published by Global Legal Group GLOBAL LEGAL INSIGHTS – BRIBERY & CORRUPTION 2021, EIGHTH EDITION Contributing Editors Jonathan Pickworth & Jo Dimmock, White & Case LLP Head of Production Suzie Levy Senior Editor Sam Friend Production Editor Nicholas Catlin Publisher Jon Martin Chief Media Officer Fraser Allan We are extremely grateful for all contributions to this edition. Special thanks are reserved for Jonathan Pickworth and Jo Dimmock of White & Case LLP for all of their assistance. Published by Global Legal Group Ltd. 59 Tanner Street, London SE1 3PL, United Kingdom Tel: +44 207 367 0720 / URL: www.glgroup.co.uk Copyright © 2020 Global Legal Group Ltd. All rights reserved No photocopying ISBN 978-1-83918-090-3 ISSN 2052-5435 This publication is for general information purposes only. It does not purport to provide comprehensive full legal or other advice. Global Legal Group Ltd. and the contributors accept no responsibility for losses that may arise from reliance upon information contained in this publication. This publication is intended to give an indication of legal issues upon which you may need advice. Full legal advice should be taken from a qualified professional when dealing with specific situations. The information contained herein is accurate as of the date of publication. Printed and bound by TJ Books Limited, Trecerus