Cambridge-Exeter Repetitive Thought Scale)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The David Attenborough Building Pembroke St, Cambridge CB2 3QY

Venue The David Attenborough Building Pembroke St, Cambridge CB2 3QY http://www.conservation.cam.ac.uk/ Cambridge Cambridge is a university city and the county town of Cambridgeshire, England, on the River Cam about 50 miles (80 km) north of London. At the United Kingdom Census 2011, its population was 123,867, including 24,488 students. There is archaeological evidence of settlement in the area in the Bronze Age and in Roman Britain; under Viking rule, Cambridge became an important trading centre. The first town charters were granted in the 12th century, although city status was not conferred until 1951. Cambridge is the home of the University of Cambridge, founded in 1209 and one of the top five universities in the world. The university includes the Cavendish Laboratory, King's College Chapel, and the Cambridge University Library. The Cambridge skyline is dominated by the last two buildings, along with the spire of the Our Lady and the English Martyrs Church, the chimney of Addenbrooke's Hospital and St John's College Chapel tower. Cambridge is at the heart of the high-technology Silicon Fen with industries such as software and bioscience and many start-up companies spun out of the university. Over 40% of the workforce have a higher education qualification, more than twice the national average. Cambridge is also home to the Cambridge Biomedical Campus, one of the largest biomedical research clusters in the world, soon to be home to AstraZeneca, a hotel and relocated Papworth Hospital. Parker's Piece hosted the first ever game of Association football. The Strawberry Fair music and arts festival and Midsummer Fairs are held on Midsummer Common, and the annual Cambridge Beer Festival takes place on Jesus Green. -

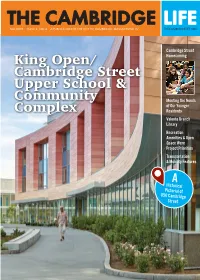

King Open/Cambridge Street Upper School & Community Complex

THE CAMBRIDGE LIFE FALL 2019 ISSUE 3, VOL.4 A PUBLICATION OF THE CITY OF CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS THECAMBRIDGELIFE.ORG Cambridge Street King Open/ Homecoming Cambridge Street Upper School & Community Meeting the Needs of Our Younger Complex Residents Valente Branch Library Recreation Amenities & Open Space Were Project Priorities Transportation & Mobility Features A Historical Pictorial of 850 Cambridge Street King Open/Cambridge Street Upper School & Community Complex Site Map Project Overview The 273,000 square foot facility at 850 Cambridge St. opened in September 2019 and houses the King Open School (JK-5), Cambridge Street Upper School (6-8), Cambridge Public Schools Administration, King Open Preschool, King Open Extended Day (KOED), Community Schools, and Valente Library The $159 million school and community complex is a net zero-ready project that consumes no fossil fuels onsite, has a highly efficient design to minimize energy demand, and incorporates the City’s largest solar array to renewably produce much of the energy needed. Remaining energy will come from the electrical grid, and when Cambridge secures 100% renewable electricity supply, the complex will achieve net zero emissions. Site amenities and open spaces include Gold Star Pool, two gyms, two basketball courts, Charles G. Rossi Bocce Court, five playgrounds, outdoor splash pad, Cambridge Street Plaza, Valente Reading Garden, a Learning Courtyard/Outdoor Classroom, and a 380-seat auditorium. “One of the important considerations throughout this entire process was to make sure we successfully met the needs of the students, staff, the school administration, the neighborhood, and users of Cambridge Street,” said Lisa Peterson, Deputy City Manager and King Open/Cambridge Street Upper School & Community Complex Project Manager, adding that an extensive community process was conducted. -

DAY 1: Cambridge

Expat Explore - Version: Sat Sep 25 2021 10:34:53 GMT+0000 (Coordinated Universal Time) Page: 1/9 Itinerary for Great Britain Christmas Tour • Expat Explore Start Point: End Point: Outside Hotel Novotel at Greenwich Outside Hotel Novotel at Greenwich station, station, 173-185 Greenwich High Road, London, SE10 173-185 Greenwich High Road, London, SE10 8JA 8JA 06:30 hrs 17:30 hrs – 20:30 hrs Hotel lobby at Holiday Inn Express, Greenwich, 85 Bugsby Way, Greenwich, London, SE10 0GD 07:00 hrs DAY 1: Start of tour in London - Cambridge - York Welcome to your Christmas tour of Great Britain! Today you will fill your lungs with fresh, English countryside air, as you depart the city of London, and head to where the grass is greener. Arriving in Cambridge, your first adventure will have you punting along the river in traditional style, taking in the stunning scenery and epic, historical buildings in the most relaxing way. Simply wonderful! The Expat Explore - Version: Sat Sep 25 2021 10:34:53 GMT+0000 (Coordinated Universal Time) Page: 2/9 afternoon sees you continuing your rural ‘rovering’, towards York, a mecca for history buffs and lovers of fine architecture and culture. Your walking tour offers fascinating insights, stories and history of the city. Tonight you will enjoy dinner in a traditional Sunday Roast dinner at a British pub - don’t forget to try the Yorkshire puddings! Experiences Cambridge punting: Float down the River Cam as you go punting - an age-old tradition in Cambridge Walking tour of York: Gain insights into this historic walled city on a walking tour with your Expat Explore tour leader. -

The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences Edited by R

Cambridge University Press 0521845548 - The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences Edited by R. Keith Sawyer Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences Learning sciences is an interdisciplinary field that studies teaching and learning. The sciences of learning include cognitive science, educational psychology, computer sci- ence, anthropology, sociology, neuroscience, and other fields. The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences shows how educators can use the learning sciences to design more effective learning environments, including school classrooms and informal settings such as science centers or after-school clubs, online distance learning, and computer- based tutoring software. The chapters in this handbook describe exciting new classroom environments, based on the latest science about how children learn. CHLS is a true handbook: readers can use it to design the schools of the future – schools that will prepare graduates to participate in a global society that is increasingly based on knowledge and innovation. R. Keith Sawyer is Associate Professor of Education at Washington University in St. Louis. He received his Ph.D. in Psychology at the University of Chicago and his S.B. in Computer Science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He studies cre- ativity, collaboration, and learning. Dr. Sawyer has written or edited eight books. His most recent book is Explaining Creativity: The Science of Human Innovation (2006). © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521845548 - The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences Edited by R. Keith Sawyer Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences Edited by R. Keith Sawyer Washington University © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521845548 - The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences Edited by R. -

Cambridge and Peterborough ICS Development Plan 31St March 2021

Cambridge and Peterborough ICS Development Plan 31st March 2021 NHS England and NHS Improvement Contents Section Page Executive summary 3 System overview 4-9 Cambridge and Peterborough ICS development plan 10-22 Gap analysis 23-30 Next steps 31-32 2 | Executive summary Cambridge and Peterborough have recently been successful in our application for ICS designation. Whilst this is a significant step in our journey as a system, we also acknowledge that there is much work to be done to make the C&P ICS a success. Our ambition is to launch our ICS in shadow form during Q4 of 2021/22 before the new ICS establishment is formalised in Q1 2022/23. There are a significant number of development steps that we need to take in order to meet this ambition, which have been grouped thematically to include: • System roles and capabilities • System leadership and accountability • System oversight and quality improvement • Leadership and people development • Financial framework and use of resources • System and digital transformation Each of these themes requires a significant amount of engagement, design work, implementation work, and throughout we must ensure that we continue to deliver business as usual activities and meet our operational and strategic targets. As a result, we have developed the following plan to set out how we aim to deliver the spectrum of activities required to ensure we progress towards our future vision whilst meeting the current needs of our local population and stakeholders. Whilst developing the plan, we have ensured it will deliver against five key development areas highlighted to us by the regional team including: finance, regional clinical leadership, workforce, provider collaboration and Local Authority engagement. -

Divcowest Welcomes Bristol Myers Squibb to Cambridge Crossing Global Biopharmaceutical Company to Join Philips, Sanofi, and Cerevel at CX in the First Half of 2023

DivcoWest Welcomes Bristol Myers Squibb to Cambridge Crossing Global Biopharmaceutical Company To Join Philips, Sanofi, and Cerevel at CX in the First Half of 2023 Cambridge, MA, (August 18, 2020) – DivcoWest announced today that it has signed a 360,000 square- foot lease with Bristol Myers Squibb (NYSE:BMY) at 250 Water Street in Cambridge Crossing (CX), the new and connected neighborhood at the intersection of Cambridge, Somerville, and Boston. The new building is currently under construction and is expected to be complete in late 2022. Bristol Myers Squibb plans to combine its Cambridge presence at the state-of-the-art laboratory and office building at 250 Water Street by the end of the first half of 2023. Dedicated to helping patients prevail over serious diseases, the biopharmaceutical company will join Philips North America, Sanofi, and Cerevel Therapeutics in the vibrant CX community. “At Cambridge Crossing (CX), our mission is to create a home for innovative companies that inspires collaboration and scientific breakthroughs. We are thrilled that global leader Bristol Myers Squibb has chosen CX as their future home,” said Mark Roopenian, Managing Director at DivcoWest. “CX is designed to be a network of forward-thinking changemakers like Bristol Myers Squibb, and we are proud to create a space for them at 250 Water Street so that they can pursue discoveries that positively transform patients’ lives.” With the addition of Bristol Myers Squibb, approximately 1.7 million square-feet of commercial space is now leased and preleased at CX. Remaining space available for lease at CX includes 110,000 SF of science and technology space at 250 Water Street and 600,000 SF in two future buildings. -

Economic Growth Potential of the Cambridge Norwich Technology Corridor

Economic Growth Potential of the Cambridge Norwich Technology Corridor Draft Final Report Adam Brown December Cambridge Econometrics [email protected] 2017 Cambridge, UK www.camecon.com Economic Growth Potential of the Cambridge Norwich Technology Corridor Cambridge Econometrics’ mission is to provide clear insights, based on rigorous and independent economic analysis, to support policy-makers and strategic planners in government, civil society and business in addressing the complex challenges facing society. Cambridge Econometrics Limited is owned by a charitable body, the Cambridge Trust for New Thinking in Economics. www.neweconomicthinking.org Cambridge Econometrics 2 Economic Growth Potential of the Cambridge Norwich Technology Corridor 1 Introduction Background Cambridge Econometrics has been commissioned by Breckland District Council and Partners to carry out an evidence review and analysis of sectoral growth potential for the Cambridge‐Norwich Technology Corridor (CNTC). The work is divided into three phases: Phase 1: Collection of economic data from a range of official government sources and presentation in graphical and GIS formats. Data on major growth sites is also to be collected and mapped. Phase 2: A statistical analysis of current sectoral strengths and weaknesses of the corridor and its sub‐areas using location quotient analysis, and an assessment of sectoral growth risks and opportunities based on national trends Phase 3: the presentation of a projection for population and economic growth for the next 15 years, combined with some recommendations for policy intervention The work builds on a previous study carried out by Bruton Knowles’ (BK, 2015), along with the marketing research of the Deyton Bell Report (2016), the New Anglia SEP (2017) and GCGP SEP (2013), and this work should be seen in the context of the recommendations outlined in those papers. -

Vital Statistics from the 1945 Exeter NH Annual Report

Vital Statistics from the 1945 Exeter NH Annual Report Marriages Date Place of Marriage Groom's Name Age Residence Groom's Parents Bride's Name Age Residence Bride's Parents 1/3/1945 Exeter Joseph L. Parent 21 Portland, ME Theodore P. Parent & Ozile Cote Ethel M. Sellick 20 Portland, ME Nelson J. Sellick & Addie B. Sellick 1/11/1945 Exeter Robert L. McMillan 20 R. Springs, NC Peyton McMillan & Lizzie Jones Shirley Lewis 21 Amesbury, MA Gilford H. Lewis & Idaletta Merchant 1/13/1945 Exeter Charles D. DeSmet, Jr. 22 St. Louis, MO Charles DeSmet & Julia A. Czerwinski Mildred V. Wasiewski 23 Exeter Stanley Wasiewski & Staffa Waleryszak 1/19/1945 Exeter John Papandrew 23 Exeter Vassileos Papendrew & Evangeline Efstathiou Betty J. Hilliard 20 Exeter Leon W. Hilliard & Marie L. Nouat 1/27/1945 Exeter William F. Roche 21 Roxbury, MA James J. Roche & Flora E. Kelley Wilma C. DuBeau 18 Roxbury, MA Ernest J. DuBeau & Elizabeth M. Lynn 1/27/1945 Exeter Roland J. Kinsman 42 Boston, MA Samuel W. Kinsman & Agnes A. Palmer Hilda A. Hunt 33 Boston, MA Theodore Hunt & Lydia Smith 2/22/1945 Exeter Wendell J. Sargent, Jr. 25 Exeter Wendell J. Sargent, Sr. & Ella Lane Audrey P. Higgins 20 Exeter Alfred H. Higgins, Sr. & Iva M. Collishaw 3/3/1945 Exeter R. M. Daughenbaugh 40 Stratham R. E. Daughenbaugh & Bessie A. Kirk Dorothy L. Welch 26 Exeter Fred R. Welch & Maude S. Stevens 3/9/1945 Rochester Clayton W. LaBree 40 Exeter Paul W. LaBree & Blanche E. Clifford Adelma E. Pelletier 22 Exeter Archie J. -

Leicester's Commonwealth

LEICESTER’S COMMONWEALTH 1 ___________________________________________________________________ The copy of a letter written by a Master of Art of Cambridge to his friend in London, concerning some talk passed of late between two worshipful and grave men about the present state and some proceedings of the Earl of Leicester and his friends in England. Conceived, spoken and published with most earnest protestation of all dutiful goodwill and affection towards her most excellent Majesty and the realm, for whose good only it is made common to many. Job cap. 20 verse 27 Revelabunt coeli iniquitatem eius, & terra consurget adversus eum. The heavens shall revile the wicked man’s iniquity, and the earth shall stand up to bear witness against him. Anno M. D. LXXXIIII. LEICESTER’S COMMONWEALTH 2 ___________________________________________________________________ The Epistle Directory To Mr. G.M. in Gracious Street in London. Dear & loving friend, I received about ten days gone your letter of the 9. of this present, wherein you demand & solicit again the thing that I so flatly denied you at my late being in your chamber - I mean, to put in writing the relation which then I made unto you of the speech had this last Christmas in my presence between my right worshipful good friend & patron & his guest the old lawyer, of some matters in our state & country. And for that you press me very seriously at this instant, both by request & many reasons, to yield to your desire herein, & not only this, but also to give my consent for the publishing of the same by such secret means as you assure me you can there find out, I have thought good to confer the whole matter with the parties themselves whom principally it concerneth (who at the receipt of your letter were not far off from me). -

The Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Local Transport Plan

Appendix 2 Report January 2020 The Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Local Transport Plan Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Combined Authority 23217301 Report January 2020 The Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Local Transport Plan Prepared by: Prepared for: Steer Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Combined 28-32 Upper Ground Authority London SE1 9PD The Incubator 2 First Floor Alconbury Weald Enterprise Campus Alconbury Weald Huntingdon Cambridgeshire PE28 4WX +44 20 7910 5000 www.steergroup.com Our ref: 23217301 Steer has prepared this material for Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Combined Authority. This material may only be used within the context and scope for which Steer has prepared it and may not be relied upon in part or whole by any third party or be used for any other purpose. Any person choosing to use any part of this material without the express and written permission of Steer shall be deemed to confirm their agreement to indemnify Steer for all loss or damage resulting therefrom. Steer has prepared this material using professional practices and procedures using information available to it at the time and as such any new information could alter the validity of the results and conclusions made. The Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Local Transport Plan | Report Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................ 6 Policy alignment ................................................................................................................. 7 Vision, -

Cambridge City Council and South Cambridgeshire District Council

CAMBRIDGE CITY COUNCIL AND SOUTH CAMBRIDGESHIRE DISTRICT COUNCIL INDOOR SPORTS FACILITY STRATEGY 2015-2031 JUNE 2016 OFFICIAL-SENSITIVE The table below lists the changes applied to the May 2016 version of the Indoor Sports Facility Strategy. Section of the Indoor Changes to the Indoor Sports Facility Strategy (RD/CSF/200) Sports Facility Strategy Whole document Reference to Indoor Facility/Facilities Strategy changed to Indoor Sports Facility Strategy Whole document Acronym IFS (for Indoor Facility/Facilities Strategy) changed to ISFS (for Indoor Sports Facility Strategy) Paragraph 2.11 Delete final sentence of paragraph as no map is provided. South Cambridgeshire District completely encircles Cambridge. South Cambridgeshire District is bordered to the northeast by East Cambridgeshire District, to the southeast by St Edmundsbury District, to the south by Uttlesford District, to the southwest by North Hertfordshire District, to the west by Central Bedfordshire and to the northwest by Huntingdonshire District. The neighbouring counties are shown on Map 2.2 below: Paragraph 5.320 Add additional sentence to the end of paragraph 5.320 to clarify the usage of squash facilities. All the pay and play squash facilities across Cambridge and South Cambridgeshire District are located on education sites; all but Kelsey Kerridge therefore have limited day time access. However, the majority of squash is played in evenings and weekends, so this is less of an issue than it is for sports hall provision. CAMBRIDGE CITY COUNCIL AND SOUTH CAMBRIDGESHIRE DISTRICT COUNCIL INDOOR SPORTS FACILITY STRATEGY TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 CAMBRIDGE AND SOUTH CAMBRIDGESHIRE DISTRICT - INDOOR SPORTS FACILITY STRATEGY (ISFS) 3 VISION 3 AIMS 3 NEEDS, PRIORITIES AND OPPORTUNITIES 4 NEW SETTLEMENTS BEYOND 2031 7 RECOMMENDATIONS 13 CAMBRIDGE AND SOUTH CAMBRIDGESHIRE DISTRICT COUNCIL - PLAYING PITCH STRATEGY (PPS) 16 2. -

An Introduction to the 1801 Cabinet & Chair Makers' Norwich Book of Prices

An Introduction to the 1801 Cabinet & Chair Makers’ Norwich Book of Prices robert williams I Norwich at the beginning of the eighteenth century was the largest provincial town in England and was also an inland port, connected to Yarmouth by the river Yare. By 1801, when the second edition of the Cabinet & Chair Makers’ Norwich Book of Prices was published, it had fallen behind as the focus of economic growth had shifted to the new and developing centres in the North and Midlands. Without the mineral resources and water power that many of these centres possessed Norwich had slipped to ninth place and was now behind the main manufacturing centres and ports, which in order of size were, Manchester, Liverpool, Birmingham, Bristol, Leeds, Shefeld, Plymouth and Newcastle/Gateshead.1 Norwich’s prosperity had been based on weaving of worsted fabric, which had developed into a wide range of quality fabrics in bright colours, and by the middle of the eighteenth century perhaps up to half of the population was employed in cloth production. As machine made cottons captured the home market and with the advent of machine spun yarn from the north of England, the cottage industry of hand spinning on which Norwich relied went into a slow decline. The manufacturers became increasingly dependent on their export trade which sufered particularly during the wars against France of 1793–1815. By 1801 Norwich was still primarily an industrial town but the weaving trade was soon to be surpassed by leather making, brewing and agricultural products as well as banking and the beginnings of the insurance business.