TALL BEECH FERN a New Beech

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Native Herbaceous Perennials and Ferns for Shade Gardens

Green Spring Gardens 4603 Green Spring Rd ● Alexandria ● VA 22312 Phone: 703-642-5173 ● TTY: 703-803-3354 www.fairfaxcounty.gov/parks/greenspring NATIVE HERBACEOUS PERENNIALS AND FERNS FOR � SHADE GARDENS IN THE WASHINGTON, D.C. AREA � Native plants are species that existed in Virginia before Jamestown, Virginia was founded in 1607. They are uniquely adapted to local conditions. Native plants provide food and shelter for a myriad of birds, butterflies, and other wildlife. Best of all, gardeners can feel the satisfaction of preserving a part of our natural heritage while enjoying the beauty of native plants in the garden. Hardy herbaceous perennials form little or no woody tissue and live for several years. Some of these plants are short-lived and may live only three years, such as wild columbine, while others can live for decades. They are a group of plants that gardeners are very passionate about because of their lovely foliage and flowers, as well as their wide variety of textures, forms, and heights. Most of these plants are deciduous and die back to the ground in the winter. Ferns, in contrast, have no flowers but grace our gardens with their beautiful foliage. Herbaceous perennials and ferns are a joy to garden with because they are easily moved to create new design combinations and provide an ever-changing scene in the garden. They are appropriate for a wide range of shade gardens, from more formal gardens to naturalistic woodland gardens. The following are useful definitions: Cultivar (cv.) – a cultivated variety designated by single quotes, such as ‘Autumn Bride’. -

Thelypteridaceae – Marsh Fern Family

THELYPTERIDACEAE – MARSH FERN FAMILY Plant: fern, terrestrial (rarely epiphytic) Root: Stem and Leaves: stems erect to creeping, usually with 2 vascular bundles, cresent-shaped; leaves either monomorphic (one leaf type) or slightly dimorphic (blade differences minor), scales mostly absent, blade pinnate to pinnate-pinnatifid (rarely by-pinnate or more divided) Fruit (Sori): sori on veins and of various shapes but usually not elongate, an indusium often with hairs, spores monolete, bilateral Other: Division Pteridophyta (Ferns) Genera: 30+ genera * Fern terminology is discussed in PLANT TERMS, a separate tab on the HOME page. WARNING – family descriptions are only a layman’s guide and should not be used as definitive THELYPTERIDACEAE – MARSH FERN FAMILY Eastern Marsh Fern; Thelypteris palustris Schott var. pubescens (G. Lawson) Fernald Eastern Marsh Fern - P1 USDA Thelypteris palustris Schott var. pubescens (G. Lawson) Fernald Thelypteridaceae (Marsh Fern Family) Near Mingo National Wildlife Refuge, Stoddard County, Missouri Notes: fern, deciduous; leaves somewhat dimorphic (pinnae of fertile leaves somewhat narrower, more erect), up to 1m, lanceolate with proximal pinnae a little shorter, mostly pinnate-pinnatifid, terminal pinnae just pinnatifid, pinnatifid segments of pinnae entire, veins usually forked, hairs on costae and often on veins; petiole smooth and straw colored; spore cases round, medial; indusia peltate to reniform (sometimes leaf blade strongly revolute); costae slightly hairy and scaly with a front groove; seeps and marshy areas; summer to fall [V Max Brown, 2017] Eastern Marsh Fern – P2 Thelypteris palustris Schott var. pubescens (G. Lawson) Fernald [V Max Brown, 2017] Sporangia Indusia Costae (midrib), veins, and sori with hairs. -

Ferns of the National Forests in Alaska

Ferns of the National Forests in Alaska United States Forest Service R10-RG-182 Department of Alaska Region June 2010 Agriculture Ferns abound in Alaska’s two national forests, the Chugach and the Tongass, which are situated on the southcentral and southeastern coast respectively. These forests contain myriad habitats where ferns thrive. Most showy are the ferns occupying the forest floor of temperate rainforest habitats. However, ferns grow in nearly all non-forested habitats such as beach meadows, wet meadows, alpine meadows, high alpine, and talus slopes. The cool, wet climate highly influenced by the Pacific Ocean creates ideal growing conditions for ferns. In the past, ferns had been loosely grouped with other spore-bearing vascular plants, often called “fern allies.” Recent genetic studies reveal surprises about the relationships among ferns and fern allies. First, ferns appear to be closely related to horsetails; in fact these plants are now grouped as ferns. Second, plants commonly called fern allies (club-mosses, spike-mosses and quillworts) are not at all related to the ferns. General relationships among members of the plant kingdom are shown in the diagram below. Ferns & Horsetails Flowering Plants Conifers Club-mosses, Spike-mosses & Quillworts Mosses & Liverworts Thirty of the fifty-four ferns and horsetails known to grow in Alaska’s national forests are described and pictured in this brochure. They are arranged in the same order as listed in the fern checklist presented on pages 26 and 27. 2 Midrib Blade Pinnule(s) Frond (leaf) Pinna Petiole (leaf stalk) Parts of a fern frond, northern wood fern (p. -

The Fern Family Blechnaceae: Old and New

ANDRÉ LUÍS DE GASPER THE FERN FAMILY BLECHNACEAE: OLD AND NEW GENERA RE-EVALUATED, USING MOLECULAR DATA Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia Vegetal do Departamento de Botânica do Instituto de Ciências Biológicas da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, como requisito parcial à obtenção do título de Doutor em Biologia Vegetal. Área de Concentração Taxonomia vegetal BELO HORIZONTE – MG 2016 ANDRÉ LUÍS DE GASPER THE FERN FAMILY BLECHNACEAE: OLD AND NEW GENERA RE-EVALUATED, USING MOLECULAR DATA Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia Vegetal do Departamento de Botânica do Instituto de Ciências Biológicas da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, como requisito parcial à obtenção do título de Doutor em Biologia Vegetal. Área de Concentração Taxonomia Vegetal Orientador: Prof. Dr. Alexandre Salino Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais Coorientador: Prof. Dr. Vinícius Antonio de Oliveira Dittrich Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora BELO HORIZONTE – MG 2016 Gasper, André Luís. 043 Thefern family blechnaceae : old and new genera re- evaluated, using molecular data [manuscrito] / André Luís Gasper. – 2016. 160 f. : il. ; 29,5 cm. Orientador: Alexandre Salino. Co-orientador: Vinícius Antonio de Oliveira Dittrich. Tese (doutorado) – Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Departamento de Botânica. 1. Filogenia - Teses. 2. Samambaia – Teses. 3. RbcL. 4. Rps4. 5. Trnl. 5. TrnF. 6. Biologia vegetal - Teses. I. Salino, Alexandre. II. Dittrich, Vinícius Antônio de Oliveira. III. Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. Departamento de Botânica. IV. Título. À Sabrina, meus pais e a vida, que não se contém! À Lucia Sevegnani, que não pode ver esta obra concluída, mas que sempre foi motivo de inspiração. -

Notes on Rust Fungi in China 4. Hosts and Distribution of <I> Hyalopsora

MYCOTAXON ISSN (print) 0093-4666 (online) 2154-8889 Mycotaxon, Ltd. ©2018 January–March 2018—Volume 133, pp. 23–29 https://doi.org/10.5248/133.23 Notes on rust fungi in China 4. Hosts and distribution of Hyalopsora aspidiotus and H. hakodatensis Jing-Xin Ji1, Zhuang Li2, Yu Li1, Jian-Yun Zhuang3, Makoto Kakishima1, 4* 1 Engineering Research Center of Chinese Ministry of Education for Edible and Medicinal Fungi, Jilin Agricultural University, Changchun, Jilin 130118, China 2 College of Plant Pathology, Shandong Agricultural University, Tai’an 271000, China 3 Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 10001, China 4 University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8572, Japan * Correspondence to: [email protected] Abstract—Hosts and distribution in China of two fern rust fungi, Hyalopsora aspidiotus and H. hakodatensis, are clarified based on new collections and examination of herbarium specimens. The ferns Athyrium iseanum, Deparia orientalis, and Phegopteris connectilis are newly identified hosts for H. hakodatensis, while Gymnocarpium jessoense represents a new host for H. aspidiotus in China. The rusts are also reported as new for several Chinese provinces. Key words—Pucciniomycetes, taxonomy, Uredinales Introduction Rust fungi on ferns—species of Hyalopsora, Milesina, and Uredinopsis (together with anamorphic taxa designated as Milesia)—are distributed mainly in temperate to cold areas, especially where their alternate hosts (Abies species) are found (Cummins & Hiratsuka 2003). Many fern rust species are believed to occur in China because of the wide range of areas suitable for their growth. However, these rust fungi have been insufficiently investigated on the mainland. Tai (1979), who listed two Hyalopsora, six Milesina, and eight Uredinopsis species, recorded most of the sixteen species from Taiwan. -

Taxonomic, Phylogenetic, and Functional Diversity of Ferns at Three Differently Disturbed Sites in Longnan County, China

diversity Article Taxonomic, Phylogenetic, and Functional Diversity of Ferns at Three Differently Disturbed Sites in Longnan County, China Xiaohua Dai 1,2,* , Chunfa Chen 1, Zhongyang Li 1 and Xuexiong Wang 1 1 Leafminer Group, School of Life Sciences, Gannan Normal University, Ganzhou 341000, China; [email protected] (C.C.); [email protected] (Z.L.); [email protected] (X.W.) 2 National Navel-Orange Engineering Research Center, Ganzhou 341000, China * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +86-137-6398-8183 Received: 16 March 2020; Accepted: 30 March 2020; Published: 1 April 2020 Abstract: Human disturbances are greatly threatening to the biodiversity of vascular plants. Compared to seed plants, the diversity patterns of ferns have been poorly studied along disturbance gradients, including aspects of their taxonomic, phylogenetic, and functional diversity. Longnan County, a biodiversity hotspot in the subtropical zone in South China, was selected to obtain a more thorough picture of the fern–disturbance relationship, in particular, the taxonomic, phylogenetic, and functional diversity of ferns at different levels of disturbance. In 90 sample plots of 5 5 m2 along roadsides × at three sites, we recorded a total of 20 families, 50 genera, and 99 species of ferns, as well as 9759 individual ferns. The sample coverage curve indicated that the sampling effort was sufficient for biodiversity analysis. In general, the taxonomic, phylogenetic, and functional diversity measured by Hill numbers of order q = 0–3 indicated that the fern diversity in Longnan County was largely influenced by the level of human disturbance, which supports the ‘increasing disturbance hypothesis’. -

Broad Beech Fern: What You Can Do to Help Broad Beech Fern (Phegopteris Hexagonoptera) Is an Understorey Species of Deciduous Forests

Saving Broad Beech Fern: What you can do to help Broad Beech Fern (Phegopteris hexagonoptera) is an understorey species of deciduous forests. It is very similar to the more common Northern Beech Fern (Phegopteris connectilis). Do you live near Broad Beech Fern? Broad Beech Fern is found only in southern Ontario and southern Quebec. Broad Beech Fern grows in maple forests with moist or wet soils. It prefers shade and thrives in forests with a closed canopy. What you can do to help Learn to identify this plant. If you are lucky enough to discover a new population of Broad Photo credit: Arieh Tal (www. nttlphoto.com) Beech Fern, be sure to report it to the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. Do not collect this plant or its parts for medicinal, ornamental or any other uses. Note “wings” on midvein between Take care during maple syrup harvesting. Avoid driving vehicles, placing equipment and lowest and second- trampling in Broad Beech Fern habitat, which lowest pair of is typically very moist or even flooded in early leaflets spring. Contact your local Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources or Conservation Authority Photo credit: Janet Novak office for additional advice if you are considering maple syrup harvest near Broad Field check Beech Fern populations. Height: up to 50 cm Avoid logging near Broad Beech Fern Leaf: 20-40 cm long; triangular shape; populations as it reduces shade and moisture required for growth. Here are a few tips if you 24 or more leaflets; lowest pair of need to harvest: leaflets tapered on both ends; midvein • Consult with your local Ontario Ministry of winged between lowest and second- Natural Resources, Conservation lowest pair of leaflets Authority or Woodlot Association before Petiole (leaf stem): slender 15-20 cm logging near the Broad Beech Fern long, smooth and straw coloured populations. -

Natural Community and Plant Inventory of Grass River Natural

Natural Community Delineation and Floristic Quality Assessments of Grass River Natural Area, Antrim County, Michigan Prepared by: Rachel Hackett, Phyllis Higman, and Liana May Michigan Natural Features Inventory PO Box 13036 Lansing, MI 48901-3036 For: Grass River Natural Area 6500 Alden Hwy, Bellaire, MI 49615 December 31, 2017 Report No. 2017-12 Funding for this project was provided by the Grass River Natural Area through a grant from the Grand Traverse Regional Community Foundation. Suggested Citation: Hackett, R.A., P. Higman, and L. May. 2017. Natural Community Delineation and Floristic Quality Assessments of Grass River Natural Area, Antrim County, Michigan. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2017-12, Lansing, MI. 64 pp. Appendices: 62 pp. Copyright 2017 Michigan State University Board of Trustees. Michigan State University Extension programs and materials are open to all without regard to race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientations, marital status, or family status. Cover photographs: Utricularia cornuta in northern fen, MI #1A, Antrim Co., Mich., June 20, 2017; Sarracenia purpurea in rich conifer swamp, DELANGE #1B, Antrim Co., MI, June 23, 2017. All photographs in report by R.A. Hackett unless otherwise noted. Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... -

The Ferns and Their Relatives (Lycophytes)

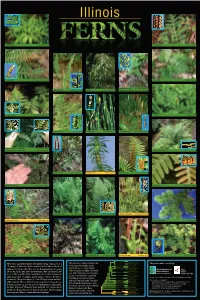

N M D R maidenhair fern Adiantum pedatum sensitive fern Onoclea sensibilis N D N N D D Christmas fern Polystichum acrostichoides bracken fern Pteridium aquilinum N D P P rattlesnake fern (top) Botrychium virginianum ebony spleenwort Asplenium platyneuron walking fern Asplenium rhizophyllum bronze grapefern (bottom) B. dissectum v. obliquum N N D D N N N R D D broad beech fern Phegopteris hexagonoptera royal fern Osmunda regalis N D N D common woodsia Woodsia obtusa scouring rush Equisetum hyemale adder’s tongue fern Ophioglossum vulgatum P P P P N D M R spinulose wood fern (left & inset) Dryopteris carthusiana marginal shield fern (right & inset) Dryopteris marginalis narrow-leaved glade fern Diplazium pycnocarpon M R N N D D purple cliff brake Pellaea atropurpurea shining fir moss Huperzia lucidula cinnamon fern Osmunda cinnamomea M R N M D R Appalachian filmy fern Trichomanes boschianum rock polypody Polypodium virginianum T N J D eastern marsh fern Thelypteris palustris silvery glade fern Deparia acrostichoides southern running pine Diphasiastrum digitatum T N J D T T black-footed quillwort Isoëtes melanopoda J Mexican mosquito fern Azolla mexicana J M R N N P P D D northern lady fern Athyrium felix-femina slender lip fern Cheilanthes feei net-veined chain fern Woodwardia areolata meadow spike moss Selaginella apoda water clover Marsilea quadrifolia Polypodiaceae Polypodium virginanum Dryopteris carthusiana he ferns and their relatives (lycophytes) living today give us a is tree shows a current concept of the Dryopteridaceae Dryopteris marginalis is poster made possible by: { Polystichum acrostichoides T evolutionary relationships among Onocleaceae Onoclea sensibilis glimpse of what the earth’s vegetation looked like hundreds of Blechnaceae Woodwardia areolata Illinois fern ( green ) and lycophyte Thelypteridaceae Phegopteris hexagonoptera millions of years ago when they were the dominant plants. -

Syllabus for Post Graduate Course in Botany (2016 – 2017 Onward)

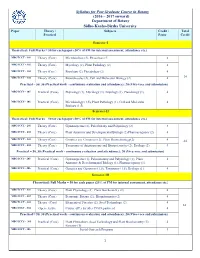

Syllabus for Post Graduate Course in Botany (2016 – 2017 onward) Department of Botany Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University Paper Theory / Subjects Credit / Total Practical Paper Credit Semester-I Theoretical: Full Marks = 50 for each paper (20% of FM for internal assessment, attendance etc.) MBOTCCT - 101 Theory (Core) Microbiology (2), Phycology (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 102 Theory (Core) Mycology (2), Plant Pathology (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 103 Theory (Core) Bryology (2), Pteridology (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 104 Theory (Core) Biomolecules (2), Cell and Molecular Biology (2) 4 24 Practical = 50, 30 (Practical work - continuous evaluation and attendance); 20 (Viva-voce and submission) MBOTCCS - 105 Practical (Core) Phycology (1), Mycology (1), Bryology (1), Pteridology (1). 4 MBOTCCS - 106 Practical (Core) Microbiology (1.5), Plant Pathology (1), Cell and Molecular 4 Biology (1.5). Semester-II Theoretical: Full Marks = 50 for each paper (20% of FM for internal assessment, attendance etc.) MBOTCCT - 201 Theory (Core) Gymnosperms (2), Paleobotany and Palynology (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 202 Theory (Core) Plant Anatomy and Developmental Biology (2) Pharmacognosy (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 203 Theory (Core) Genetics and Genomics (2), Plant Biotechnology(2) 4 24 MBOTCCT - 204 Theory (Core) Taxonomy of Angiosperms and Biosystematics (2), Ecology (2) 4 Practical = 50, 30 (Practical work - continuous evaluation and attendance); 20 (Viva-voce and submission) MBOTCCS - 205 Practical (Core) Gymnosperms (1), Palaeobotany and Palynology (1), Plant 4 Anatomy & Developmental Biology (1), Pharmacognosy (1). MBOTCCS - 206 Practical (Core) Genetics and Genomics (1.5), Taxonomy (1.5), Ecology (1). 4 Semester-III Theoretical: Full Marks = 50 for each paper (20% of FM for internal assessment, attendance etc.) MBOTCCT - 301 Theory (Core) Plant Physiology (2), Plant Biochemistry (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 302 Theory (Core) Economic Botany (2), Bioinformatics (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 303 Theory (Core) Elements of Forestry (2), Seed Technology (2). -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE ORCID ID: 0000-0003-0186-6546 Gar W. Rothwell Edwin and Ruth Kennedy Distinguished Professor Emeritus Department of Environmental and Plant Biology Porter Hall 401E T: 740 593 1129 Ohio University F: 740 593 1130 Athens, OH 45701 E: [email protected] also Courtesy Professor Department of Botany and PlantPathology Oregon State University T: 541 737- 5252 Corvallis, OR 97331 E: [email protected] Education Ph.D.,1973 University of Alberta (Botany) M.S., 1969 University of Illinois, Chicago (Biology) B.A., 1966 Central Washington University (Biology) Academic Awards and Honors 2018 International Organisation of Palaeobotany lifetime Honorary Membership 2014 Fellow of the Paleontological Society 2009 Distinguished Fellow of the Botanical Society of America 2004 Ohio University Distinguished Professor 2002 Michael A. Cichan Award, Botanical Society of America 1999-2004 Ohio University Presidential Research Scholar in Biomedical and Life Sciences 1993 Edgar T. Wherry Award, Botanical Society of America 1991-1992 Outstanding Graduate Faculty Award, Ohio University 1982-1983 Chairman, Paleobotanical Section, Botanical Society of America 1972-1973 University of Alberta Dissertation Fellow 1971 Paleobotanical (Isabel Cookson) Award, Botanical Society of America Positions Held 2011-present Courtesy Professor of Botany and Plant Pathology, Oregon State University 2008-2009 Visiting Senior Researcher, University of Alberta 2004-present Edwin and Ruth Kennedy Distinguished Professor of Environmental and Plant Biology, Ohio -

Fern Classification

16 Fern classification ALAN R. SMITH, KATHLEEN M. PRYER, ERIC SCHUETTPELZ, PETRA KORALL, HARALD SCHNEIDER, AND PAUL G. WOLF 16.1 Introduction and historical summary / Over the past 70 years, many fern classifications, nearly all based on morphology, most explicitly or implicitly phylogenetic, have been proposed. The most complete and commonly used classifications, some intended primar• ily as herbarium (filing) schemes, are summarized in Table 16.1, and include: Christensen (1938), Copeland (1947), Holttum (1947, 1949), Nayar (1970), Bierhorst (1971), Crabbe et al. (1975), Pichi Sermolli (1977), Ching (1978), Tryon and Tryon (1982), Kramer (in Kubitzki, 1990), Hennipman (1996), and Stevenson and Loconte (1996). Other classifications or trees implying relationships, some with a regional focus, include Bower (1926), Ching (1940), Dickason (1946), Wagner (1969), Tagawa and Iwatsuki (1972), Holttum (1973), and Mickel (1974). Tryon (1952) and Pichi Sermolli (1973) reviewed and reproduced many of these and still earlier classifica• tions, and Pichi Sermolli (1970, 1981, 1982, 1986) also summarized information on family names of ferns. Smith (1996) provided a summary and discussion of recent classifications. With the advent of cladistic methods and molecular sequencing techniques, there has been an increased interest in classifications reflecting evolutionary relationships. Phylogenetic studies robustly support a basal dichotomy within vascular plants, separating the lycophytes (less than 1 % of extant vascular plants) from the euphyllophytes (Figure 16.l; Raubeson and Jansen, 1992, Kenrick and Crane, 1997; Pryer et al., 2001a, 2004a, 2004b; Qiu et al., 2006). Living euphyl• lophytes, in turn, comprise two major clades: spermatophytes (seed plants), which are in excess of 260 000 species (Thorne, 2002; Scotland and Wortley, Biology and Evolution of Ferns and Lycopliytes, ed.