From Ter-Petrossian to Kocharian: Explaining Continuity in Armenian Foreign Policy, 1991–2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asala & ARF 'Veterans' in Armenia and the Nagorno-Karabakh Region

Karabakh Christopher GUNN Coastal Carolina University ASALA & ARF ‘VETERANS’ IN ARMENIA AND THE NAGORNO-KARABAKH REGION OF AZERBAIJAN Conclusion. See the beginning in IRS- Heritage, 3 (35) 2018 Emblem of ASALA y 1990, Armenia or Nagorno-Karabakh were, arguably, the only two places in the world that Bformer ASALA terrorists could safely go, and not fear pursuit, in one form or another, and it seems that most of them did, indeed, eventually end up in Armenia (36). Not all of the ASALA veterans took up arms, how- ever. Some like, Alex Yenikomshian, former director of the Monte Melkonian Fund and the current Sardarapat Movement leader, who was permanently blinded in October 1980 when a bomb he was preparing explod- ed prematurely in his hotel room, were not capable of actually participating in the fighting (37). Others, like Varoujan Garabedian, the terrorist behind the attack on the Orly Airport in Paris in 1983, who emigrated to Armenia when he was pardoned by the French govern- ment in April 2001 and released from prison, arrived too late (38). Based on the documents and material avail- able today in English, there were at least eight ASALA 48 www.irs-az.com 4(36), AUTUMN 2018 Poster of the Armenian Legion in the troops of fascist Germany and photograph of Garegin Nzhdeh – terrorist and founder of Tseghakronism veterans who can be identified who were actively en- tia group of approximately 50 men, and played a major gaged in the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh (39), but role in the assault and occupation of the Kelbajar region undoubtedly there were more. -

"From Ter-Petrosian to Kocharian: Leadership Change in Armenia

UC Berkeley Recent Work Title From Ter-Petrosian to Kocharian: Leadership Change in Armenia Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0c2794v4 Author Astourian, Stephan H. Publication Date 2000 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California University of California, Berkeley FROM TER-PETROSIAN TO KOCHARIAN: LEADERSHIP CHANGE IN ARMENIA Stephan H. Astourian Berkeley Program in Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies Working Paper Series This PDF document preserves the page numbering of the printed version for accuracy of citation. When viewed with Acrobat Reader, the printed page numbers will not correspond with the electronic numbering. The Berkeley Program in Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies (BPS) is a leading center for graduate training on the Soviet Union and its successor states in the United States. Founded in 1983 as part of a nationwide effort to reinvigorate the field, BPSs mission has been to train a new cohort of scholars and professionals in both cross-disciplinary social science methodology and theory as well as the history, languages, and cultures of the former Soviet Union; to carry out an innovative program of scholarly research and publication on the Soviet Union and its successor states; and to undertake an active public outreach program for the local community, other national and international academic centers, and the U.S. and other governments. Berkeley Program in Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies University of California, Berkeley Institute of Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies 260 Stephens Hall #2304 Berkeley, California 94720-2304 Tel: (510) 643-6737 [email protected] http://socrates.berkeley.edu/~bsp/ FROM TER-PETROSIAN TO KOCHARIAN: LEADERSHIP CHANGE IN ARMENIA Stephan H. -

Conflicts in the Caucasus. Ethnic Conflicts of Small Nations Or Political Battles of Great Powers?

Conflicts in the Caucasus. Ethnic Conflicts of Small Nations or Political Battles of Great Powers? Senior Project Thesis Luka Liparteliani Submitted in Partial fulfillment Of the Requirements for the degree of Degree Earned In International Economy and Relations State University of New York Empire State College 2021 Reader: Dr. Max Hilaire Statutory Declaration / Čestné prohlášení I, Luka Liparteliani, declare that the paper entitled: Conflicts In The Caucasus. Ethnic Conflicts Of Small Nations Or Political Battles of Great Powers? was written by myself independently, using the sources and information listed in the list of references. I am aware that my work will be published in accordance with § 47b of Act No. 111/1998 Coll., On Higher Education Institutions, as amended, and in accordance with the valid publication guidelines for university graduate theses. Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto práci vypracoval/a samostatně s použitím uvedené literatury a zdrojů informací. Jsem vědom/a, že moje práce bude zveřejněna v souladu s § 47b zákona č. 111/1998 Sb., o vysokých školách ve znění pozdějších předpisů, a v souladu s platnou Směrnicí o zveřejňování vysokoškolských závěrečných prací. In Prague, 24.04.2021 Luka Liparteliani 1 Acknowledgements As any written work in the world would not have been done without suggestions and advice of others, this paper has been inspired and influenced by people that I am grateful for. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to professor Dr. Max Hilarie for he has guided me through the journey of working on this thesis. I would also like to thank professor Oscar Hidalgo for his inspirational courses and for giving me the knowledge in the political science field, without which this paper could not have been done. -

Societal Perceptions of the Conflict in Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh

Caucasus Institute Policy Paper Societal Perceptions of the Conflict in Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh Hrant Mikaelian © 2017 Caucasus Institute, Yerevan Policy Paper www.c-i.am SOCIETAL PERCEPTIONS OF THE CONFLICT IN ARMENIA AND NAGORNO-KARABAKH Caucasus Institute Policy Paper Yerevan, December 2017 Author: Hrant Mikaelian, Research Fellow at the Caucasus Institute Editors: Nina Iskandaryan, Liana Avetisyan 1 This policy paper is part of a project on Engaging society and decision-makers in dialogue for peace over the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict implemented by the Caucasus Institute with support from the UK Government’s Conflict, Stability and Security Fund. Page The project is aimed at reducing internal vulnerabilities created by unresolved conflicts and inter-ethnic tension, and increasing the space for constructive dialogue on conflict resolution, creating capacities and incentives for stakeholders in Armenia and Nagorno- Karabakh for resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, reconciliation and peace- building. Opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and may not reflect the views of the Caucasus Institute or any other organization, including project sponsors and organizations with which the authors are affiliated. All personal and geographical names used in this volume are spelled the way they were spelled by the authors. SOCIETAL PERCEPTIONS OF THE CONFLICT IN ARMENIA AND NAGORNO-KARABAKH War or Peace? Public Opinion and Expectations ............................................................................... -

Thomas De Waal the Caucasus

THE CAUCASUS This page intentionally left blank THE CAUCASUS AN INTRODUCTION Thomas de Waal 1 2010 1 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2010 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data de Waal, Thomas. The Caucasus : an introduction / Thomas de Waal. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-539976-9; 978-0-19-539977-6 (pbk.) 1. Caucasus Region—Politics and government. 2. Caucasus Region—History. 3. Caucasus Region—Relations—Russia. 4. Russia—Relations—Caucasus Region. 5. Caucasus Region—Relations—Soviet Union. 6. Soviet Union—Relations—Caucasus Region. I. Title. DK509.D33 2010 947.5—dc22 2009052376 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper To Zoe This page intentionally left blank Contents Introduction 1 1. -

Former President Kocharyan Arrested for Using Deadly Force in 2008 Russian, Armenian KOCHARYAN, from Page 1 Serious Concern About It

AUG 4, 2018 Mirror-SpeTHE ARMENIAN ctator Volume LXXXIX, NO. 3, Issue 4547 $ 2.00 NEWS The First English Language Armenian Weekly in the United States Since 1932 INBRIEF Armenian Companies Former President Kocharyan Arrested To Take Part in Japan Tourism Expo For Using Deadly Force in 2008 YEREVAN (Armenpress) — Seven Armenian tourism companies will participate in Tourism YEREVAN (RFE/RL and Armenpress) — politically motivated. of a disputed presidential election held in Expo Japan 2018, from September 20 to 23, in Lawyers for former President Robert One of them, Aram Orbelian, said that February 2008, two months before he com- Tokyo, the Small and Medium Entrepreneurship Kocharyan said on Monday, July 30, that they expect Armenia’s Court of Appeals to pleted his second and final term. The accusa- Development National Center (SME DNC) founda- they will appeal a Yerevan district court’s start considering their petition this week. tion stems from the use of deadly force on tion announced. decision to allow law-enforcement authori- Kocharyan was arrested late on Friday, July On July 27, SME DNC executive director Arshak ties to arrest the former Armenian presi- 27, one day after being charged with “over- Grigoryan, president of the Tourism Committee, dent on coup charges which he denies as throwing the constitutional order” in the wake Hripsime Grigoryan, and executive director of the Tourism Development Foundation of Armenia Ara Khzmalyan signed a memorandum of cooperation for properly preparing and successfully participat- ing in the expo. According to the document, the sides will exchange their experience, knowledge and infor- mation with each other. -

Forced Displacement in the Nagorny Karabakh Conflict: Return and Its Alternatives

Forced displacement in the Nagorny Karabakh conflict: return and its alternatives August 2011 conciliation resources Place-names in the Nagorny Karabakh conflict are contested. Place-names within Nagorny Karabakh itself have been contested throughout the conflict. Place-names in the adjacent occupied territories have become increasingly contested over time in some, but not all (and not official), Armenian sources. Contributors have used their preferred terms without editorial restrictions. Variant spellings of the same name (e.g., Nagorny Karabakh vs Nagorno-Karabakh, Sumgait vs Sumqayit) have also been used in this publication according to authors’ preferences. Terminology used in the contributors’ biographies reflects their choices, not those of Conciliation Resources or the European Union. For the map at the end of the publication, Conciliation Resources has used the place-names current in 1988; where appropriate, alternative names are given in brackets in the text at first usage. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of Conciliation Resources or the European Union. Altered street sign in Shusha (known as Shushi to Armenians). Source: bbcrussian.com Contents Executive summary and introduction to the Karabakh Contact Group 5 The Contact Group papers 1 Return and its alternatives: international law, norms and practices, and dilemmas of ethnocratic power, implementation, justice and development 7 Gerard Toal 2 Return and its alternatives: perspectives -

Dissertation Final Aug 31 Formatted

Identity Gerrymandering: How the Armenian State Constructs and Controls “Its” Diaspora by Kristin Talinn Rebecca Cavoukian A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science University of Toronto © Copyright by Kristin Cavoukian 2016 Identity Gerrymandering: How the Armenian State Constructs and Controls “Its” Diaspora Kristin Talinn Rebecca Cavoukian Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science University of Toronto 2016 Abstract This dissertation examines the Republic of Armenia (RA) and its elites’ attempts to reframe state-diaspora relations in ways that served state interests. After 17 years of relatively rocky relations, in 2008, a new Ministry of Diaspora was created that offered little in the way of policy output. Instead, it engaged in “identity gerrymandering,” broadening the category of diaspora from its accepted reference to post-1915 genocide refugees and their descendants, to include Armenians living throughout the post-Soviet region who had never identified as such. This diluted the pool of critical, oppositional diasporans with culturally closer and more compliant emigrants. The new ministry also favoured geographically based, hierarchical diaspora organizations, and “quiet” strategies of dissent. Since these were ultimately attempts to define membership in the nation, and informal, affective ties to the state, the Ministry of Diaspora acted as a “discursive power ministry,” with boundary-defining and maintenance functions reminiscent of the physical border policing functions of traditional power ministries. These efforts were directed at three different “diasporas:” the Armenians of Russia, whom RA elites wished to mold into the new “model” diaspora, the Armenians of Georgia, whose indigeneity claims they sought to discourage, and the “established” western diaspora, whose contentious public ii critique they sought to disarm. -

Contesting National Identities in an Ethnically Homogeneous State: the Case of Armenian Democratization

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 4-2009 Contesting National Identities in an Ethnically Homogeneous State: The Case of Armenian Democratization Arus Harutyunyan Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Harutyunyan, Arus, "Contesting National Identities in an Ethnically Homogeneous State: The Case of Armenian Democratization" (2009). Dissertations. 667. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/667 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONTESTING NATIONAL IDENTITIES IN AN ETHNICALLY HOMOGENEOUS STATE: THE CASE OF ARMENIAN DEMOCRATIZATION by Arus Harutyunyan A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science Advisor: Emily Hauptmann, Ph.D. Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan April 2009 Copyright by Arus Harutyunyan 2009 UMI Number: 3354070 Copyright 2009 by Harutyunyan, Arus All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Setting Football Records with Axis. Axis Network Cameras Form Backbone of Security Video Surveillance System at Vazgen Sargsyan Republican Stadium in Armenia

Case study Setting football records with Axis. Axis network cameras form backbone of security video surveillance system at Vazgen Sargsyan Republican Stadium in Armenia. Organization: Football Federation of Armenia Location: Yerevan, Armenia Industry segment: Stadiums/Venues Application: Safety and security Axis partner: IU Networks, Abris Distribution, Inc Mission Vazgen Sargsyan Republican Stadium was built in the IU Networks installed AXIS Q6045-E, AXIS P5414-E, capital of Armenia in 1937. Modernization of the and AXIS P5534-E PTZ Network Cameras as well as stadium started in the late 2000s with the goal of AXIS P1354-E Fixed Network Cameras and AXIS Camera bringing it up to UEFA standards to host the national Station software for video surveillance. football team. In particular, the stadium had to be equipped inside and outside with fixed color cameras Result with pan/tilt motors, allowing for highly detailed images Currently, the Republican Stadium is equipped with 56 that could be controlled from the stadium management Axis IP cameras arranged in such a way as to cover center. every square meter of the territory, from the main entrance to the terrace, and identify people and objects Solution inside the viewing angle. Such a video surveillance When designing the security video surveillance system system ensures security and efficient monitoring at for Vazgen Sargsyan Stadium, the Football Federation every entrance and exit, prevents possible accidents, of Armenia decided to go for Axis products. Such crite- and continuously operates in any climatic conditions. ria as image quality, high durability of cameras, and the altogether top-of-the-line quality of the products were taken into account. -

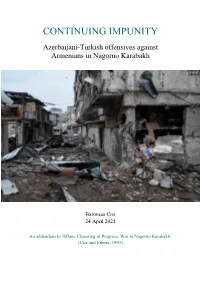

Continuing Impunity

CONTINUING IMPUNITY Azerbaijani-Turkish offensives against Armenians in Nagorno Karabakh Baroness Cox 24 April 2021 An addendum to ‘Ethnic Cleansing in Progress: War in Nagorno Karabakh’ (Cox and Eibner, 1993) CONTENTS Acknowledgements page 1 Introduction page 1 Background page 3 The 44-Day War page 3 Conclusion page 27 Appendix: ‘The Spirit of Armenia’ page 29 1. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to record my profound sympathy for all who suffered – and continue to suffer – as a result of the recent war and my deep gratitude to all whom I met for sharing their experiences and concerns. These include, during my previous visit in November 2020: the Presidents of Armenia and Nagorno Karabakh; the Human Rights Ombudsmen for Armenia and Nagorno Karabakh; members of the National Assembly of Armenia; Zori Balayan and his family, including his son Hayk who had recently returned from the frontline with his injured son; Father Hovhannes and all whom I met at Dadivank; and the refugees in Armenia. I pay special tribute to Vardan Tadevosyan, along with his inspirational staff at Stepanakert’s Rehabilitation Centre, who continue to co-ordinate the treatment of some of the most vulnerable members of their community from Yerevan and Stepanakert. Their actions stand as a beacon of hope in the midst of indescribable suffering. I also wish to express my profound gratitude to Artemis Gregorian for her phenomenal support for the work of my small NGO Humanitarian Aid Relief Trust, together with arrangements for many visits. She is rightly recognised as a Heroine of Artsakh as she stayed there throughout all the years of the previous war and has remained since then making an essential contribution to the community. -

A Lose-Lose Perspective for the Future of Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia-Azerbaijan Relations

GETTING TO KNOW NAGORNO-KARABAKH Rethinking-and-Changing: A Lose-Lose Perspective for the Future of Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia-Azerbaijan Relations Francesco TRUPIA, PhD Postdoc Fellow at the University Centre of Excellence Interacting Minds, Societies and Environment (IMSErt) - Nicolaus Copernicus University, Toruń – Poland The ‘Second Karabakh War’ has arguably ended the oldest conflict of the post-Soviet region. Nevertheless, the aftermath of the latest military confrontation between the Artsakh Armenian forces and Azerbaijan has made very little room for peacebuilding. Six months after, Armenia and Azerbaijan’s civil societies continue to take antagonistic approaches to the post-2020 ‘Nagorno-Karabakh issue’, which remains far from being solved and properly settled down. At present, both conflictual positions show two connected yet different processes of negotiations and reconciliation1. While on the one hand the two Caucasian nations are struggling to maximise their opportunities that stemmed from the post-2020 status quo, on the other hand suspicious ideas and radical plots have been circulating and casting dark shadows on the future of the Nagorno-Karabakh region and the South Caucasus. The recent crisis over the Syunik and Gegharkunik borderlands between Armenia and Azerbaijan, is here instructive for assessing the highly volatile scenario. As the title states, this essay attempts to provide a different perspective over the Nagorno-Karabakh rivalry through the lens of the ‘rethinking-and-changing’ approach rather than the old-fashioned paradigm of ‘forgiving-and-forgetting’. It is not here question the transition from warfare to peace scenario for overcoming the new status quo and avoiding new escalations. Conversely, this essay raises the following question: whom the current peacebuilding process is designed for? Hence, the choice to knowingly overlook the historical as well as latest military events in Nagorno-Karabakh has the scope of focusing on a future-oriented perspective of reconciliation.