ABSTRACT: This Pape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Resistance of the Monks RIGHTS Buddhism and Activism in Burma WATCH

Burma HUMAN The Resistance of the Monks RIGHTS Buddhism and Activism in Burma WATCH The Resistance of the Monks Buddhism and Activism in Burma Copyright © 2009 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-544-X Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org September 2009 1-56432-544-X The Resistance of the Monks Buddhism and Activism in Burma I. Summary and Key Recommendations....................................................................................... 1 Methodology ....................................................................................................................... 26 II. Burma: A Long Tradition of Buddhist Activism ....................................................................... 27 Buddhism in Independent Burma During the Parliamentary Period ...................................... 33 Buddhism and the State After the 1962 Military Takeover ................................................... -

Myanmar AI Index: ASA 16/034/2007 Date: 23 October 2007

Amnesty.org feature Eighteen years of persecution in Myanmar AI Index: ASA 16/034/2007 Date: 23 October 2007 On 24 October 2007, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi will have spent 12 of the last 18 years under detention. She may be the best known of Myanmar’s prisoners of conscience, but she is far from the only one. Amnesty International believes that, even before the recent violent crackdown on peaceful protesters, there were more than 1,150 political prisoners in the country. Prisoners of conscience among these include senior political representatives of the ethnic minorities as well as members of the NLD and student activist groups. To mark the 18th year of Aung San Suu Kyi's persecution by the Myanmar, Amnesty International seeks to draw the world's attention to four people who symbolise all those in detention and suffering persecution in Myanmar. These include Aung San Suu Kyi herself; U Win Tin, Myanmar's longest-serving prisoner of conscience; U Khun Htun Oo, who is serving a 93 year sentence; and Zaw Htet Ko Ko, who was arrested after participating in the recent demonstrations in the country. Read more about these four people: Daw Aung San Suu Kyi Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s party won the general elections in Myanmar in 1990. But, instead of taking her position as national leader, she was kept under house arrest by the military authorities and remains so today. At 62, Aung San Suu Kyi is the General Secretary and a co-founder of Myanmar’s main opposition party, the National League for Democracy (NLD). -

Summary of Current Situation Monthly Trend Analysis

Chronology of Political Prisoners in Burma for February 2009 Summary of current situation There are a total of 2,128 political prisoners in Burma. 1 These include: CATEGORY NUMBER Monks 220 Members of Parliament 15 Students 229 88 Generation Students Group 47 Women 186 NLD members 456 Members of the Human Rights Defenders and Promoters network 42 Ethnic nationalities 203 Cyclone Nargis volunteers 20 Teachers 26 Media activists 43 Lawyers 15 In poor health 115 Since the protests in August 2007 leading to last September’s Saffron Revolution, a total of 1,052 activists have been arrested and are still in detention. Monthly trend analysis 250 In the month of February 2009, 4 200 activists were arrested, 5 were sentenced, and 30 were released. On 150 Arrested 20 February the military regime Sentenced 100 Released announced an amnesty for 6,313 50 prisoners, beginning 21 February. To date AAPP has been able to confirm 0 Nov-08 Dec-08 Jan-09 Feb-09 the release of just 30 political prisoners. This month the UN Special Envoy Ibrahim Gambari and the UN Special Rapporteur on the human rights situation in Myanmar Tomas Ojea Quintana both visited Burma. At the time of the Special Rapporteur’s visit, political prisoners U Thura aka Zarganar, Zaw Thet Htway, Thant Sin Aung, Tin Maung Aye aka Gatone, Kay Thi Aung aka Ma Ei, Wai Myo Htoo aka Yan Naing, Su Su Nway and Nay Myo Kyaw aka Nay Phone Latt all had their sentences reduced. However they all still face long prison terms of between 8 years and 6 months, and 35 years. -

Bullets in the Alms Bowl

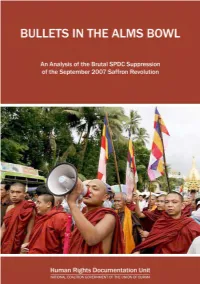

BULLETS IN THE ALMS BOWL An Analysis of the Brutal SPDC Suppression of the September 2007 Saffron Revolution March 2008 This report is dedicated to the memory of all those who lost their lives for their part in the September 2007 pro-democracy protests in the struggle for justice and democracy in Burma. May that memory not fade May your death not be in vain May our voices never be silenced Bullets in the Alms Bowl An Analysis of the Brutal SPDC Suppression of the September 2007 Saffron Revolution Written, edited and published by the Human Rights Documentation Unit March 2008 © Copyright March 2008 by the Human Rights Documentation Unit The Human Rights Documentation Unit (HRDU) is indebted to all those who had the courage to not only participate in the September protests, but also to share their stories with us and in doing so made this report possible. The HRDU would like to thank those individuals and organizations who provided us with information and helped to confirm many of the reports that we received. Though we cannot mention many of you by name, we are grateful for your support. The HRDU would also like to thank the Irish Government who funded the publication of this report through its Department of Foreign Affairs. Front Cover: A procession of Buddhist monks marching through downtown Rangoon on 27 September 2007. Despite the peaceful nature of the demonstrations, the SPDC cracked down on protestors with disproportionate lethal force [© EPA]. Rear Cover (clockwise from top): An assembly of Buddhist monks stage a peaceful protest before a police barricade near Shwedagon Pagoda in Rangoon on 26 September 2007 [© Reuters]; Security personnel stepped up security at key locations around Rangoon on 28 September 2007 in preparation for further protests [© Reuters]; A Buddhist monk holding a placard which carried the message on the minds of all protestors, Sangha and civilian alike. -

The Massive Increase in Burma's Political Prisoners September 2008

The Future in the Dark: The Massive Increase in Burma’s Political Prisoners September 2008 Jointly Produced by: Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (Burma) and United States Campaign for Burma The Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (Burma) (AAPP) is dedicated to provide aid to political prisoners in Burma and their family members. The AAPP also monitors and records the situation of all political prisoners and condition of prisons and reports to the international community. For further information about the AAPP, please visit to our website at www.aappb.org. The United States Campaign for Burma (USCB) is a U.S.-based membership organization dedicated to empowering grassroots activists around the world to bring about an end to the military dictatorship in Burma. Through public education, leadership development initiatives, conferences, and advocacy campaigns at local, national and international levels, USCB works to empower Americans and Burmese dissidents-in-exile to promote freedom, democracy, and human rights in Burma and raise awareness about the egregious human rights violations committed by Burma’s military regime. For further information about the USCB, please visit to our website at www.uscampaignforburma.org 1 Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (Burma) P.O Box 93, Mae Sot, Tak Province 63110, Thailand [email protected], www.aappb.org United States Campaign for Burma 1444 N Street, NW, Suite A2, Washington, DC 20005 Tel: (202) 234 8022, Fax: (202) 234 8044 [email protected], www.uscampaignforburma.org -

11-Monthly Chronology of Burma Political Prisoners for November 2008

Chronology of Political Prisoners in Burma for November 2008 Summary of current situation There are a total of 2164 political prisoners in Burma. These include: CATEGORY NUMBER Monks 220 Members of Parliament 17 Students 271 Women 184 NLD members 472 Members of the Human Rights Defenders and Promoters network 37 Ethnic nationalities 211 Cyclone Nargis volunteers 22 Teachers 25 Media activists 42 Lawyers 13 In poor health 106 Since the protests in August 2007, leading to last September’s Saffron Revolution, a total of 1057 activists have been arrested. Monthly trend analysis In the month of November, at least 215 250 political activists have been sentenced, 200 the majority of whom were arrested in 1 50 Arrested connection with last year’s popular Sentenced uprising in August and September. They 1 00 Released include 33 88 Generation Students Group 50 members, 65 National League for 0 Democracy members and 27 monks. Sep-08 Oct-08 Nov-08 The regime began trials of political prisoners arrested in connection with last year’s Saffron Revolution on 8 October last year. Since then, at least 384 activists have been sentenced, most of them in November this year. This month at least 215 activists were sentenced and 19 were arrested. This follows the monthly trend for October, when there were 45 sentenced and 18 arrested. The statistics confirm reports, which first emerged in October, that the regime has instructed its judiciary to expedite the trials of detained political activists. This month Burma’s flawed justice system has handed out severe sentences to leading political activists. -

Burma Page 1 of 30

2008 Human Rights Report: Burma Page 1 of 30 2008 Human Rights Report: Burma BUREAU OF DEMOCRACY, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND LABOR 2008 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices February 25, 2009 Burma, with an estimated population of 54 million, is ruled by a highly authoritarian military regime dominated by the majority ethnic Burman group. The State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), led by Senior General Than Shwe, was the country's de facto government. Military officers wielded the ultimate authority at each level of government. In 1990 prodemocracy parties won more than 80 percent of the seats in a general parliamentary election, but the regime continued to ignore the results. The military government controlled the security forces without civilian oversight. The regime continued to abridge the right of citizens to change their government and committed other severe human rights abuses. Government security forces allowed custodial deaths to occur and committed other extrajudicial killings, disappearances, rape, and torture. The government detained civic activists indefinitely and without charges. In addition regime-sponsored mass-member organizations engaged in harassment, abuse, and detention of human rights and prodemocracy activists. The government abused prisoners and detainees, held persons in harsh and life-threatening conditions, routinely used incommunicado detention, and imprisoned citizens arbitrarily for political motives. The army continued its attacks on ethnic minority villagers. Aung San Suu Kyi, general secretary of the National League for Democracy (NLD), and NLD Vice-Chairman Tin Oo remained under house arrest. The government routinely infringed on citizens' privacy and restricted freedom of speech, press, assembly, association, religion, and movement. -

The Future in the Dark: the Massive Increase in Burma's Political

The Future in the Dark: The Massive Increase in Burma’s Political Prisoners, September 2008 Jointly Produced by Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (Burma) and United States Campaign for Burma The Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (Burma) (AAPP) is dedicated to provide aid to political prisoners in Burma and their family members. The AAPP also monitors and records the situation of all political prisoners and condition of prisons and reports to the international community. For further information about the AAPP, please visit to our website at www.aappb.org . The United States Campaign for Burma (USCB) is a U.S.-based membership organization dedicated to empowering grassroots activists around the world to bring about an end to the military dictatorship in Burma. Through public education, leadership development initiatives, conferences, and advocacy campaigns at local, national and international levels, USCB works to empower Americans and Burmese dissidents-in-exile to promote freedom, democracy, and human rights in Burma and raise awareness about the egregious human rights violations committed by Burma’s military regime. For further information about the USCB, please visit to our website at www.uscampaignforburma.org 1 Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (Burma) P.O Box 93, Mae Sot, Tak Province 63110, Thailand [email protected] , www.aappb.org United States Campaign for Burma 1444 N Street, NW, Suite A2, Washington, DC 20005 Tel: (202) 234 8022, Fax: (202) 234 8044 [email protected], www.uscampaignforburma.org -

Burma Page 1 of 30

2009 Human Rights Report: Burma Page 1 of 30 Home » Under Secretary for Democracy and Global Affairs » Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor » Releases » Human Rights Reports » 2009 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices » East Asia and the Pacific » Burma 2009 Human Rights Report: Burma BUREAU OF DEMOCRACY, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND LABOR 2009 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices March 11, 2010 Burma, with an estimated population of 54 million, is ruled by a highly authoritarian military regime dominated by the majority ethnic Burman group. The State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), led by Senior General Than Shwe, was the country's de facto government. Military officers wielded the ultimate authority at each level of government. In 1990 prodemocracy parties won more than 80 percent of the seats in a general parliamentary election, but the regime continued to ignore the results. In May 2008 the regime held a referendum on its draft constitution and declared the constitution had been approved by 92.48 percent of voters, a figure no independent observers believed was valid. The constitution specifies that the SPDC will continue to rule until a new parliament is convened, scheduled to take place following national elections in 2010. The military government controlled the security forces without civilian oversight. The regime continued to abridge the right of citizens to change their government and committed other severe human rights abuses. Government security forces allowed custodial deaths to occur and committed extrajudicial killings, disappearances, rape, and torture. The government detained civic activists indefinitely and without charges. In addition regime-sponsored mass-member organizations engaged in harassment, abuse, and detention of human rights and prodemocracy activists. -

B816 Dear Mr Kouchner, ASEM Summit

Bernard Kouchner Foreign Minister of the Republic of France French Presidency of the EU Brussels, 17 October 2008 Ref: B816 Dear Mr Kouchner, ASEM summit: human rights must be on the agenda Ahead of the 7th ASEM summit, on 24th and 25th October in Beijing, we are writing to urge the French Presidency to use the opportunity to raise, with the government of Myanmar through ASEM, concerns about ongoing human rights abuses in that country. In particular, we would like to highlight three current concerns regarding the situation in Myanmar: the new constitution and the 2010 elections; persecution of peaceful political dissent; and crimes against humanity in eastern Myanmar. The new constitution and the 2010 elections Myanmar’s government announced in February 2008 that it had completed the drafting of a new constitution, and despite the devastating consequences of Cyclone Nargis just a week earlier, which killed tens of thousands of people and displaced nearly a million more, held referendums on the constitution on 10 and 24 May. The government claimed that 92.4% of the population approved the constitution. Amnesty International is deeply concerned that, rather than attempting to introduce the rule of law and respect for human rights to Myanmar, this constitutional process seeks to perpetuate and legitimise the government’s continuing human rights abuses and ensure impunity for past, present and future violations. We are concerned that despite the obvious flaws in the drafting process and in the actual constitution, the referendum has been described as a positive or meaningful process on several occasions, both regionally and within the wider international community, since the government of Myanmar have presented it as part of their ‘Roadmap to Democracy’, paving the way for elections to be held in 2010. -

1. Frontcover-SCRUBBED

1 Profiles of '88 Generation Students The '88 Generation Students group is comprised of Burma's most prominent human rights activists after Nobel Peace Prize recipient Aung San Suu Kyi. After Burma's military regime drastically raised the price of fuel in August 2007, the '88 Generation Students organized a non-violent protest walk in which they were joined by hundreds of everyday Burmese people. The '88 students were immediately arrested and have been held ever since. Anger at the arrests and the Burmese regime's treatment of Buddhist monks spiraled into last September's "Saffron Revolution" that saw hundreds of thousands of Buddhist monks marching peacefully for change. In late August 2008, in a blunt rejection of the United Nations Security Council and just days after two UN envoys traveled to Burma seeking democratic change and improvements in human rights, the country's military regime hauled dozens of the '88 Generation Students from prison cells into court in order to begin "sham" trials that will likely result in over 150 years of incarceration. List of '88 Generation Students 1. Min Ko Naing 21. Thet Thet Aung (F) 2. Ko Ko Gyi 22. Ma Lay Mon (F) 3. Ko Pyone Cho 23. Ma Hnin May Aung@ Nobel 4. Min Zeya Aye (F) 5. Ko Mya Aye 24. Daw San San Tin (F) 6. Kyaw Min Yu @ Jimmy 25. Tharape Theint Theint Htun (F) 7. Zeya 26. Ma Aye Thida (F) 8. Kyaw Kyaw Htwe @ Markee 27. Ma Nwe Hnin Yee @ Noe Noe 9. Antbwe Kyaw (F) 10. Pandeik Htun 28. -

MYANMAR: Free the 88 Generation Students

MYANMAR: Free the 88 Generation Students Htay Kywe Mie Mie Zaw Htet Ko Ko Activists Htay Kywe, Mie Mie and Zaw Htet Ko Ko were arrested in the hunt for the people behind the major anti-government protests that began in August 2007, which were brought to an end by a violent crackdown by the authorities in late September. They are now facing a range of politically motivated charges. Amnesty International considers them to be prisoners of conscience. They are at risk of torture. All three are members of a pro-democracy group, the 88 Generation Students. They were arrested in the early hours of 13 October 2007 in a house where they were hiding, on the outskirts of the former capital, Yangon. The owner of the house and two other members of the 88 Generation Students were arrested with them. The 88 Generation Students group is largely made up of leaders of a massive pro-democracy uprising of 1988, when Myanmar had been under military rule for 26 years and the economy was in ruins. Htay Kywe, Mie Mie and Zaw Htet Ko Ko were involved in the early protest marches of August 2007, against sudden increases in fuel prices imposed by the state, but were soon forced into hiding as the authorities launched a search for those they thought were the leaders of the protests, in particular Htay Kywe. During the night of 21 August, 13 key 88 Generation Students activists were arrested. Htay Kywe and Mie Mie have each received 65 years' imprisonment. In November Mie Mie was transferred to Katha prison, Sagaing Division in northwestern Myanmar.