Activist Preferences, Party Size and Issue Selection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extremism in the Electoral Arena: Challenging the Myth of American Exceptionalism Gur Bligh

BYU Law Review Volume 2008 | Issue 5 Article 2 12-1-2008 Extremism in the Electoral Arena: Challenging the Myth of American Exceptionalism Gur Bligh Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/lawreview Part of the Election Law Commons Recommended Citation Gur Bligh, Extremism in the Electoral Arena: Challenging the Myth of American Exceptionalism, 2008 BYU L. Rev. 1367 (2008). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/lawreview/vol2008/iss5/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Brigham Young University Law Review at BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Law Review by an authorized editor of BYU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BLIGH.FIN 11/24/2008 5:55 PM Extremism in the Electoral Arena: Challenging the Myth of American Exceptionalism Gur Bligh Abstract: This Article explores the limitations that the American electoral system imposes upon extremist parties and candidates. Its thesis is that extremists, and particularly anti-liberal extremists, are excluded from the American electoral arena through a combination of direct and indirect mechanisms. This claim challenges the crucial premise of American constitutional theory that the free speech doctrine is a distinct area of “American exceptionalism.” That theory posits that the American strict adherence to viewpoint neutrality, the strong emphasis upon the “dissenter,” and the freedom granted to extremist speakers is exceptional among liberal democracies. The Article argues that once we focus upon the electoral arena as a distinct arena, we discover that in this domain of core political expression, dissenting extremists are marginalized and blocked and their viewpoints are not represented. -

Doomed to Failure? UKIP and the Organisational Challenges Facing Right-Wing Populist Anti-Political Establishment Parties

Abedi, A. and Lundberg, T.C. (2009) Doomed to failure? UKIP and the organisational challenges facing right-wing populist anti-political establishment parties. Parliamentary Affairs, 62 (1). pp. 72-87. ISSN 0031-2290 http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/41367 Deposited on: 22 October 2010 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Doomed to Failure? UKIP and the Organisational Challenges Facing Right-Wing Populist Anti-Political Establishment Parties This is a pre-copy editing, author-produced version of an article accepted for publication in Parliamentary Affairs following peer review. The definitive publisher-authenticated version (‘Doomed to Failure? UKIP and the Organisational Challenges Facing Right- Wing Populist Anti-Political Establishment Parties’, Parliamentary Affairs, 62(1): 72-87, January 2009) is available online at http://pa.oxfordjournals.org/content/62/1/72.abstract. Amir Abedi Thomas Carl Lundberg Department of Political Science School of Social and Political Sciences Western Washington University Adam Smith Building 516 High Street 40 Bute Gardens Bellingham, WA 98225-9082 University of Glasgow U.S.A. Glasgow G12 8RT +1-360-650-4143 Scotland [email protected] 0141-330 5144 [email protected] Abstract: Using the UK Independence Party (UKIP), we examine the effects of sudden electoral success on an Anti-Political Establishment (APE) party. The pressures of aspiring to government necessitate organisational structures resembling those of mainstream parties, while this aspiration challenges APE parties because they differ not just in terms of their policy profiles, but also in their more ‘unorthodox’ organisational make-up, inextricably linked to their electoral appeal. -

LGBTQ Election 2015 Update1

LGBTQ EQUALITY & Northern Ireland’s Political Parties An independent survey General Election 2015 UPDATED VERSION (1) In April 2015 I emailed all the political parties in Northern Ireland that have candidates standing the the 2015 General Election. I enclosed a list of questions about their policies and active records on important lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans* and queer issues. The following pages contain the original information and questions sent to the parties, along with their replies and some additonal facts about each party’s record on LGBTQ rights. All replies are printed exactly as received, except where editied (with due respect and care for key facts) to keep them roughly around the requested 150 word limit. Parties are listed in the order their answers were returned. Where parties have not responded, I have researched their available policies, manifestos and records online and compiled some information. While most of us who identfy as LGBT or Q are unlikely to vote based on a party’s LGBTQ policies alone, it does help to know what each party thinks of some of the issues that effect our lives. And, more importantly, what they have already done and what they plan to do to tackle some of the serious problems caused by homophobia and transphobia; invisibility; institutionalised discrimination and exclusion. I hope that it will be updated and added to over time. This is an independent survey. It has no agenda other than to give each party an opportunity put on paper what they intend to do to help us build a more equal Northern Ireland in terms of sexual orientation and gender identity. -

Partisan Dealignment and the Rise of the Minor Party at the 2015 General Election

MEDIA@LSE MSc Dissertation Series Compiled by Bart Cammaerts, Nick Anstead and Richard Stupart “The centre must hold” Partisan dealignment and the rise of the minor party at the 2015 general election Peter Carrol MSc in Politics and Communication Other dissertations of the series are available online here: http://www.lse.ac.uk/media@lse/research/mediaWorkingPapers/Electroni cMScDissertationSeries.aspx MSc Dissertation of Peter Carrol Dissertation submitted to the Department of Media and Communications, London School of Economics and Political Science, August 2016, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the MSc in Politics and Communication. Supervised by Professor Nick Couldry. The author can be contacted at: [email protected] Published by Media@LSE, London School of Economics and Political Science ("LSE"), Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE. The LSE is a School of the University of London. It is a Charity and is incorporated in England as a company limited by guarantee under the Companies Act (Reg number 70527). Copyright, Peter Carrol © 2017. The authors have asserted their moral rights. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. In the interests of providing a free flow of debate, views expressed in this dissertation are not necessarily those of the compilers or the LSE. 2 MSc Dissertation of Peter Carrol “The centre must hold” Partisan dealignment and the rise of the minor party at the 2015 general election Peter Carrol ABSTRACT For much of Britain’s post-war history, Labour or the Conservatives have formed a majority government, even when winning less than half of the popular vote. -

Although Many European Radical Left Parties

Peace, T. (2013) All I'm asking, is for a little respect: assessing the performance of Britain's most successful radical left party. Parliamentary Affairs, 66(2), pp. 405-424. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/144518/ Deposited on: 21 July 2017 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk 2 All I’m asking, is for a little Respect: assessing the performance of Britain’s most successful radical left party BY TIMOTHY PEACE1 ABSTRACT This article offers an overview of the genesis, development and decline of the Respect Party, a rare example of a radical left party which has achieved some degree of success in the UK. It analyses the party’s electoral fortunes and the reasons for its inability to expand on its early breakthroughs in East London and Birmingham. Respect received much of its support from Muslim voters, although the mere presence of Muslims in a given area was not enough for Respect candidates to get elected. Indeed, despite criticism of the party for courting only Muslims, it did not aim to draw its support from these voters alone. Moreover, its reliance on young people and investment in local campaigning on specific political issues was often in opposition to the traditional ethnic politics which have characterised the electoral process in some areas. When the British public awoke on the morning of Friday 6th May 2005 most would have been unsurprised to discover that the Labour Party had clung on to power but with a reduced majority, as had been widely predicted. -

Coalition in a Plurality System: Explaining Party System

Coalition in a Plurality System: Explaining Party System Fragmentation in Britain Jane Green Ed Fieldhouse Chris Prosser University of Manchester Paper prepared for the UC Berkeley British Politics Group election conference, 2nd September 2015. Abstract Electoral system theories expect proportional systems to enhance minor party voting and plurality electoral systems to reduce it. This paper illustrates how the likelihood of coalition government results in incentives to vote for minor parties in the absence of proportional representation. We advance a theory of why expectations of coalition government enhance strategic and sincere voting for minor parties. We demonstrate support for our theory using analyses of vote choices in the 2015 British general election. The findings of this paper are important for electoral system theories. They reveal that so-called proportional electoral system effects may arise, in part, due to the presence of coalition government that so often accompanies proportional representation. The findings also shed light on an important trend in British politics towards the fragmentation of the party system and a marked increase in this tendency in the 2015 British general election. 2 The 2015 general election result saw the Conservative party win a majority of seats in the House of Commons after a period of governing in coalition with the Liberal Democrats. At first glance the result may look like a return to the classic two-party majoritarian government under a plurality electoral system. But this conclusion would be wrong. 2015 represents a high watermark for votes for 'other' parties - those parties challenging the traditional establishment parties in Westminster. Vote shares for UKIP leapt from 3.1% to 12.6%, the Greens from 1.0% to 3.8%, the SNP leapt from 19.9% to 50% in Scotland and Plaid Cymru saw a small increase from 11.3% to 12.1% in Wales. -

Information on Cases

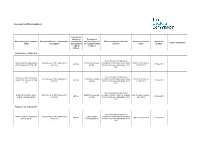

Casework and Investigations Decision on offence or Decision on Name and type of regulated Potential offence or contravention contravention sanction (imposed Brief summary of reason for Outcome or current Status last Further information entity investigated (by regulated on regulated entity decision status updated entity or or officer) officer) Published on 21 May 2019 The Commission considered, in Liberal Democrats (Kensington Late delivery of 2017 statement of £200 (fixed monetary accordance with the enforcement policy, Paid on initial notice on Offence 21 May 2019 and Chelsea accounting unit) accounts penalty) that sanctions were appropriate in this 25 April 2019 case. The Commission considered, in Liberal Democrats (Camborne, Late delivery of 2017 statement of £200 (fixed monetary accordance with the enforcement policy, Paid on initial notice on Redruth and Hayle accounting Offence 21 May 2019 accounts penalty) that sanctions were appropriate in this 25 April 2019 unit) case. The Commission considered, in Scottish Democratic Alliance Late delivery of 2017 statement of £200 (fixed monetary accordance with the enforcement policy, Due for payment by 12 Offence 21 May 2019 (registered political party) accounts penalty) that sanctions were appropriate in this June 2019 case. Published on 16 April 2019 The Commission considered, in British Resistance (registered Late delivery of 2017 statement of £300 (variable accordance with the enforcement policy, Offence Paid on 23 April 2019 21 May 2019 political party) accounts monetary penalty) that sanctions were appropriate in this case. The Commission considered, in Due for payment by 3 The Entertainment Party Late delivery of 2017 statement of £200 (fixed monetary accordance with the enforcement policy, May 2019. -

Independents in Australian Parliaments

The Age of Independence? Independents in Australian Parliaments Mark Rodrigues and Scott Brenton* Abstract Over the past 30 years, independent candidates have improved their share of the vote in Australian elections. The number of independents elected to sit in Australian parliaments is still small, but it is growing. In 2004 Brian Costar and Jennifer Curtin examined the rise of independents and noted that independents ‘hold an allure for an increasing number of electors disenchanted with the ageing party system’ (p. 8). This paper provides an overview of the current representation of independents in Australia’s parliaments taking into account the most recent election results. The second part of the paper examines trends and makes observations concerning the influence of former party affiliations to the success of independents, the representa- tion of independents in rural and regional areas, and the extent to which independ- ents, rather than minor parties, are threats to the major parities. There have been 14 Australian elections at the federal, state and territory level since Costar and Curtain observed the allure of independents. But do independents still hold such an allure? Introduction The year 2009 marks the centenary of the two-party system of parliamentary democracy in Australia. It was in May 1909 that the Protectionist and Anti-Socialist parties joined forces to create the Commonwealth Liberal Party and form a united opposition against the Australian Labor Party (ALP) Government at the federal level.1 Most states had seen the creation of Liberal and Labor parties by 1910. Following the 1910 federal election the number of parties represented in the House * Dr Mark Rodrigues (Senior Researcher) and Dr Scott Brenton (2009 Australian Parliamentary Fellow), Politics and Public Administration Section, Australian Parliamentary Library. -

Building Political Parties

Building political parties: Reforming legal regulations and internal rules Pippa Norris Harvard University Report commissioned by International IDEA 2004 1 Contents 1. Executive summary........................................................................................................................... 3 2. The role and function of parties....................................................................................................... 3 3. Principles guiding the legal regulation of parties ........................................................................... 5 3.1. The legal regulation of nomination, campaigning, and elections .................................................................. 6 3.2 The nomination stage: party registration and ballot access ......................................................................... 8 3.3 The campaign stage: funding and media access...................................................................................... 12 3.4 The electoral system: electoral rules and party competition....................................................................... 13 3.5: Conclusions: the challenges of the legal framework ................................................................................ 17 4. Strengthening the internal life of political parties......................................................................... 20 4.1 Promoting internal democracy within political parties ............................................................................. 20 4.2 Building -

The Impact of Minor Parties on Major Party Vote Shares: an Examination of State Legislative Races

The Impact of Minor Parties on Major Party Vote Shares: An Examination of State Legislative Races William M. Salka Professor of Political Science Eastern Connecticut State University Willimantic, CT 06226 [email protected] Abstract: Minor parties have long operated on the fringe of the American electoral scene. As a result, little investigation has been done on the impact of these minor party candidates in legislative elections. Outside of academe, however, minor parties have been gaining increased attention as American voters become more disillusioned with the options offered by the two major parties. This study seeks to examine the impact of minor party candidates on legislative elections in an effort to fill this gap in the literature. Using elections from sixteen states during the 2000s, the study explores the impact that minor party candidates have on the vote shares of major party candidates, testing three competing theories to explain that impact. The results suggest that minor parties may be the preferred option for some voters who are not represented by the major party platforms. Paper prepared for presentation at the Western Political Science Association Annual Meeting, Hollywood, California, March 28 – 30, 2013. Minor political parties have long operated on the fringe of American electoral politics. Despite the fact that they have existed since the 1820s, running for office at all levels of government and in all regions of the country, these parties are rarely able to field candidates that are competitive in the American two-party system (Herrnson 2002; Gillespie 1993). As a result, states have traditionally imposed barriers on which candidates can appear on the ballot. -

The Misguided Rejection of Fusion Voting by State Legislatures and the Supreme Court

THE MISGUIDED REJECTION OF FUSION VOTING BY STATE LEGISLATURES AND THE SUPREME COURT LYNN ADELMAN* The American political system is no longer perceived as the gold standard that it once was.1 And with good reason. “The United States ranks outside the top 20 countries in the Corruption Perception Index.”2 “U.S. voter turnout trails most other developed countries.”3 Congressional approval ratings are around 20%, “and polling shows that partisan animosity is at an all-time high.”4 Beginning in the 1970’s, “the economy stopped working the way it had for all of our modern history—with steady generational increases in income and living standards.”5 Since then, America has been plagued by unprecedented inequality and large portions of the population have done worse not better.6 In the meantime, the Electoral College gives the decisive losers of the national popular vote effective control of the national government.7 Under these circumstances, many knowledgeable observers believe that moving toward a multiparty democracy would improve the quality of representation, “reduce partisan gridlock, lead to positive incremental change and increase . voter satisfaction.”8 And there is no question that third parties can provide important public benefits. They bring substantially more variety to the country’s political landscape. Sometimes in American history third parties have brought neglected points of view to the forefront, articulating concerns that the major parties failed to address.9 For example, third parties played an important role in bringing about the abolition of slavery and the establishment of women’s suffrage.10 The Greenback Party and the Prohibition Party both raised issues that were otherwise ignored.11 Third parties have also had a significant impact on European democracies as, for example, when the Green Party in Germany raised environmental issues that the social democrats and conservatives ignored.12 If voters had more choices, it is likely that they would show up more often at the * Lynn Adelman is a U.S. -

Party Political Broadcasts

Party Political Broadcasts Standard Note: SN/PC/03354 Last updated: 17 March 2015 Author: Isobel White and Oonagh Gay Section Parliament and Constitution Centre This note sets out the current arrangements for party political broadcasts including their allocation, frequency, scheduling, length and content. Details are given of the BBC’s final allocation criteria for party election broadcasts (PEBs) in 2015 as well as Ofcom’s rules on PEBs for commercial broadcasters. Ofcom carried out a consultation in early 2015 about the composition of its list of major political parties, each of which are entitled to at least two PEBs by the commercial broadcasters. On 16 March 2015 Ofcom published a statement on the results of the consultation and the revised list of major parties. UKIP is included on the list but not the Green Party. The term ‘party political broadcasts’ (PPBs) is used generically here to refer to party election broadcasts (PEBs), referendum campaign broadcasts (RCBs) and the party political broadcasts which have been linked to specific political events such as the Budget and Queen’s Speech. The Note also makes reference to the long-standing ban on political advertising in the UK and the questions this raises in terms of freedom of expression and compatibility with the European Convention on Human Rights. This information is provided to Members of Parliament in support of their parliamentary duties and is not intended to address the specific circumstances of any particular individual. It should not be relied upon as being up to date; the law or policies may have changed since it was last updated; and it should not be relied upon as legal or professional advice or as a substitute for it.