Treating Variants and Complications in Anxiety Disorders Handbook of Treating Variants and Complications in Anxiety Disorders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Debbie Sookman Is an Outstanding Contribution to the Science and Clinical Practice Related to the Full Range of Obsessive Com- Pulsive Disorder

Downloaded by [New York University] at 04:59 12 August 2016 “I strongly recommend this expert clinical guide to the psychological treat- ment of obsessive compulsive disorders. The depth of Dr. Sookman’s clinical experience and her command of the literature are evident in the thorough coverage of assessment procedures, how to optimize the effects of therapy and deal with problems. The numerous case illustrations are well-chosen and clearly described.” —S. Rachman, Emeritus Professor, Institute of Psychiatry, London University, and University of British Columbia. “Specialized Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Obsessive Compulsive Disorder: An Expert Clinician Guidebook by Dr. Debbie Sookman is an outstanding contribution to the science and clinical practice related to the full range of Obsessive Com- pulsive Disorder. This is an excellent book in every way imaginable. Clearly written and organized, Sookman provides a critical and scholarly review of the state of the art on OCD. Every researcher and clinician can benefit from this superb book. The reader benefits from the considerable clinical expe- rience and scholarship that Dr Sookman possesses, while learning specific and powerful tools in helping those who suffer from OCD. Case examples illustrate the importance of conceptualization and the value of empirically supported treatments. I am particularly impressed that Sookman was able to balance such sophistication in her critical and scientific understanding of OCD, while still writing a clear and concise book on the topic. This is a book I will recommend to both beginning clinicians in training and to seasoned researchers and practitioners.” —Robert L. Leahy, Ph.D., Director, American Institute for Cognitive Therapy “Dr. -

2019 Report to the Governor and General Assembly

2019 Report to the Governor and General Assembly Virginia Department of Health Report on the Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal Infections and Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome Advisory Council PANDAS/PANS Advisory Council 2019 Report to the General Assembly Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 Background 4 PANDAS/PANS in Virginia 5 Status Report on PANDAS/PANS Advisory Council Activities 5 Summary and Future Plans 7 Recommendations 7 References 10 Appendix A – PANDAS/PANS Advisory Council and Subcommittee Members 11 Appendix B – November 26, 2018 Meeting Minutes 12 Appendix C – March 22, 2019 Subcommittee Meeting Minutes 17 Appendix D – March 25, 2019 Subcommittee Meeting Minutes 18 Appendix E – April 8, 2019 Meeting Minutes 20 Appendix F – May 20, 2019 Subcommittee Meeting Minutes 24 Appendix G – June 20, 2019 Meeting Minutes 25 Appendix H – September 23, 2019 Meeting Minutes 28 Appendix I – Suggestions for Marketing PANDAS/PANS Resources 31 Appendix J – Discussion Questions Handout 32 Appendix K – PANDAS/PANS Resources 33 Page 2 of 33 PANDAS/PANS Advisory Council 2019 Report to the General Assembly Executive Summary The Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal Infections (PANDAS) and Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome (PANS) advisory council is established in the Code of Virginia [§32.1-73.9] to advise the Commissioner of Health on research, diagnosis, treatment and education relating to PANDAS and PANS. The advisory council is required to report to the Governor and General Assembly by December 1st of each year recommendations related to the following: 1. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of PANDAS and PANS 2. -

Importance of Streptococci Infections in Childhood Neuropsychiatric Disorders

THE MEDICAL BULLETIN OF SISLI ETFAL HOSPITAL DOI: 10.14744/SEMB.2017.65487 Med Bull Sisli Etfal Hosp 2019;53(4):441–444 Case Report Importance of Streptococci Infections in Childhood Neuropsychiatric Disorders Serkan Kırık,1 Olcay Güngör,1 Yasemin Kırık2 1Department of Pediatric Neurology, Sutcu Imam University Faculty of Medicine, Kahramanmaras, Turkey 2Department of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Necip Fazil State Hospital, Kahramanmaras, Turkey Abstract Paediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococci (PANDAS) are important neuropsychiatric disor- ders in childhood. Streptococcus pyogenes infection associated with tics, obsessive-compulsive disorders, and chorea co-occur- rence is important. Swedo et al. have increased the awareness of this situation since 1998. How streptococcal infections give rise to this condition is not clear yet, but the severity of the symptoms is reduced by the treatment of streptococcal infections is important. Eight-year- nine-month-old girl presented with complaints of a 2-year history of upper respiratory tract infections and increased severity of blinking of eyes, throat cleaning, tic disorder and obsession with hand cleaning. In addition, choreiform movements were present and fluoxetine did not improve the symptoms. The patient was followed-up and treated with PANDAS pre-diagnosis. Streptococcus treatment and prophylaxis decreased the patient’s complaints. A six-year-four months old boy, admitted with abnormal hand and body movements, which increased severity after the school period, and causing deteriorated fine motor skills during infectious periods for two years. There were also complaints with vocal tics and obsessive-compulsive disorder in the form of throat cleaning. Treatment of S. pyogenes was administered in throat culture. -

Illinois Pandas/Pans Advisory Council

ILLINOIS PANDAS/PANS ADVISORY COUNCIL 2020 Report December 20, 2020 Compiled by: Wendy C Nawara, MSW Dareen Siri, MD, FAAAAI, FACAAI ILLINOIS PANDAS/PANS ADVISORY COUNCIL – 2020 REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS ILLINOIS PANDAS/PANS ADVISORY COUNCIL ................................................................................. 3 UNDERSTANDING PANDAS/PANS ................................................................................................... 4 Clinical Presentation ........................................................................................................... 4 Epidemiology/Demographics .............................................................................................. 5 Etiology and Disease Mechanisms for PANDAS (Post-streptococcal symptoms) .......................... 6 STANDARD DIAGNOSTIC AND TREATMENT GUIDELINES ............................................................... 7 Absolute Criteria ................................................................................................................. 7 Major Criteria ...................................................................................................................... 7 Minor Criteria Group 1 ........................................................................................................ 7 Minor Criteria Group 2 ........................................................................................................ 7 Additional Supporting Evidence......................................................................................... -

How a Controversial Condition Called PANDAS Is Gaining Ground on Autism

Spectrum | Autism Research News https://www.spectrumnews.org DEEP DIVE How a controversial condition called PANDAS is gaining ground on autism BY BRENDAN BORRELL 8 JANUARY 2020 Illustration and animation by Vanessa Branchi Adam Elliott was 2 years old when his parents began to suspect he might have autism. Adam had trouble making eye contact — one telltale sign of the condition — and there were other hints as well. He was a calm, inquisitive child most of the time, but some days at preschool, he would become unfocused and uncoordinated, fumbling with scissors as he tried to cut paper for art projects. By the time Adam entered elementary school, his traits had worsened. He began to experience severe separation anxiety and sensory overload in the noisy classroom. He became aggressive. When he was 6, for example, he believed his best friend was saying nasty things about him and scratched the friend in the face with a pencil. At home, Adam would often walk in circles, filled with anxiety. He eventually became so afraid that his food was poisoned, he refused to eat for long periods of time. Adam’s parents took him to a dozen different specialists during this time, including occupational therapists and psychologists. None were willing to attach a label to Adam’s condition, recalls his mother, Wendy Elliott. One doctor diagnosed Adam with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and prescribed amphetamine/dextroamphetamine (Adderall), but it did little to quell the boy’s obsessive thoughts and behaviors. By 2015, when Adam was 8, Elliott began to fear she might have to have him hospitalized. -

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Tourette's Disorder

JOURNAL OF CHILD AND ADOLESCENT PSYCHOPHARMACOLOGY Volume 20, Number 4, 2010 Guest Editorial ª Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. Pp. 235–236 DOI: 10.1089/cap.2010.2041 Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Tourette’s Disorder: Where Are We Now? Barbara J. Coffey, M.D., M.S.1 and Judith Rapoport, M.D.2 his special issue of the Journal provides an update on pedi- circuits involved in TD, which will allow clinicians to target spe- Tatric obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and Tourette’s cific types of tics with more specific treatments. disorder (TD): where are we now, and where are we going? Tic Dr. Parraga and colleagues review pharmacotherapy for TD; an disorders and OCD are quite common in clinical practice; up to interesting historical report is included. For example, Itard (1825) 20% of school-age children develop tics, and 2–4% of prepubertal described ‘‘application of leeches along the spine, and thighs… or children may develop OCD. There is also a bidirectional overlap of cold river baths, … massages and gymnastics’’; Gilles de la Tourette tics and OCD symptoms, in that OCD symptoms have been re- himself in his original case reports in 1885 acknowledged tremen- ported in as many as 60% of patients with TD, while patients with dous difficulties in treating his patients, and reported using ‘‘isola- OCD may have a 20% lifetime risk of having tics. There are sim- tion, tonics, hydrotherapy and static electricity. …’’ We have come ilarities in phenomenology, psychiatric co-morbidity, genetic vul- along way since then, but there is still a long way to go in identifi- nerability, and approaches to treatment in both pediatric-onset cation of effective and safe treatments. -

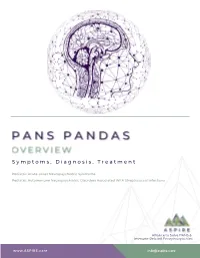

ASPIRE PANS Overview Packet

S y m p t o m s , D i a g n o s i s , T r e a t m e n t Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated With Streptococcal Infections Alliance to Solve PANS & Immune-Related Encephalopathies www.ASPIRE.care [email protected] 1. Abrupt, acute onset of 1. Presence of OCD and/or tics, Obsessive-compulsive disorder and/or particularly multiple, complex or Severe restricted food intake unusual tics 2. Concurrent presence of additional 2. Age Requirement (Symptoms of the behavioral or neurological symptoms disorder first become evident with similarly acute onset and severity between 3 years of age and puberty) from at least 2 of the 7 following categories: Acute onset and episodic (relapsing- 3. remitting) course 1.Anxiety, separation anxiety 2.Emotional lability or depression 3.Irritability, aggression, and/or 4. Association with Group A Streptococcal oppositional behaviors (GAS) infection 4.Behavioral or developmental regression 5.Deterioration in school performance (loss 5. Association with Neurological of math skills, handwriting changes, Abnormalities ADHD-like behaviors, executive functioning, etc.) Note: Comorbid neuropsychiatric symptoms are 6.Sensory or motor abnormalities, tics universally present in PANDAS, similar to the 7.Somatic signs: sleep disturbances, diagnostic criteria for PANS with similarly abrupt enuresis, or urinary frequency onset/exacerbation as the primary symptoms of Symptoms are not better explained by a PANDAS. In particular, the somatic symptoms 3. such as urinary frequency, mydriasis, and known neurologic or medical disorder insomnia, help differentiate PANDAS from 4. Age requirement – None Tourette syndrome or non-PANDAS OCD. -

Differential Binding of Antibodies in PANDAS Patients to Cholinergic Interneurons in the Striatum

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Brain Behav Manuscript Author Immun. Author Manuscript Author manuscript; available in PMC 2019 March 01. Published in final edited form as: Brain Behav Immun. 2018 March ; 69: 304–311. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2017.12.004. Differential binding of antibodies in PANDAS patients to cholinergic interneurons in the striatum Luciana Frick, Ph.D.1,#, Maximiliano Rapanelli, Ph.D.1,#, Kantiya Jindachomthong, BS1, Paul Grant, MD4, James F. Leckman, MD, Ph.D.2,3, Susan Swedo, MD4, Kyle Williams, MD, Ph.D.5,*, and Christopher Pittenger, MD, Ph.D.1,2,3,6,* 1Department of Psychiatry, Yale University 2Department of Psychology, Yale University 3Child Study Center, Yale University 4Pediatrics and Developmental Neuroscience Branch, National Institute of Mental Health 5Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, and Harvard Medical School 6Interdepartmental Neuroscience Program, Yale University Abstract Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorder Associated with Streptococcus, or PANDAS, is a syndrome of acute childhood onset of obsessive-compulsive disorder and other neuropsychiatric symptoms in the aftermath of an infection with Group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus (GABHS). Its pathophysiology remains unclear. PANDAS has been proposed to result from cross-reactivity of antibodies raised against GABHS with brain antigens, but the targets of these antibodies are unclear and may be heterogeneous. We developed an in vivo assay in mice to characterize the cellular targets of antibodies in serum from individuals with PANDAS. We focus on striatal interneurons, which have been implicated in the pathogenesis of tic disorders. Sera from children with well-characterized PANDAS (n = 5) from a previously described clinical trial (NCT01281969), and matched controls, were infused into the striatum of mice; antibody binding to interneurons was characterized using immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy. -

PRACTICE GUIDELINE for the Treatment of Patients with Eating Disorders Third Edition

PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR THE Treatment of Patients With Eating Disorders Third Edition WORK GROUP ON EATING DISORDERS Joel Yager, M.D., Chair Michael J. Devlin, M.D. Katherine A. Halmi, M.D. David B. Herzog, M.D. James E. Mitchell III, M.D. Pauline Powers, M.D. Kathryn J. Zerbe, M.D. This practice guideline was approved in December 2005 and published in June 2006. A guideline watch, summarizing significant developments in the scientific literature since publication of this guideline, may be available in the Psychiatric Practice section of the APA web site at www.psych.org. 1 Copyright 2010, American Psychiatric Association. APA makes this practice guideline freely available to promote its dissemination and use; however, copyright protections are enforced in full. No part of this guideline may be reproduced except as permitted under Sections 107 and 108 of U.S. Copyright Act. For permission for reuse, visit APPI Permissions & Licensing Center at http://www.appi.org/CustomerService/Pages/Permissions.aspx. AMERICAN PSYCHIATRIC ASSOCIATION STEERING COMMITTEE ON PRACTICE GUIDELINES John S. McIntyre, M.D., Chair Sara C. Charles, M.D., Vice-Chair Daniel J. Anzia, M.D. Ian A. Cook, M.D. Molly T. Finnerty, M.D. Bradley R. Johnson, M.D. James E. Nininger, M.D. Paul Summergrad, M.D. Sherwyn M. Woods, M.D., Ph.D. Joel Yager, M.D. AREA AND COMPONENT LIAISONS Robert Pyles, M.D. (Area I) C. Deborah Cross, M.D. (Area II) Roger Peele, M.D. (Area III) Daniel J. Anzia, M.D. (Area IV) John P. D. Shemo, M.D. (Area V) Lawrence Lurie, M.D. -

Panel and Study Groups

Neuropsychopharmacology (2012) 38, S1–S78 & 2012 American College of Neuropsychopharmacology All rights reserved 0893-133X/12 www.neuropsychopharmacology.org S1 Monday, December 03, 2012 Conclusions: The signaling differences identified in this study have important implications in screening different KOR agonists and antago- nists having distinctly different ligand directed signaling properties. Mini Panel Disclosure: C. Chavkin, Part 1: Consulting for Trevena 2010-2011, 1. Renaissance in Opioid Biology: From Preclinical Concepts to Part 2: Contract with Trevena 2010-2011. Clinical Practice 1.2 The Place of Opiates in the Cortico-basal Ganglia Reward 1.1 Molecular Basis for Kappa Opioid Receptor Antagonism: Circuit Implications of Ligand-directed Signaling for the Development of Novel Antidepressants Suzanne Haber* Charles Chavkin* University of Rochester, Rochester, New York University of Washington, Seattle, Washington Background: Reward is a central component for driving incentive- based learning, appropriate responses to stimuli, and habit Background: Preclinical studies have demonstrated the role of formation. Pathology in this circuit is associated with several stress-induced dynorphin release in mediating a component of the diseases including addition. The ventral medial prefrontal cortex anxiogenic and aversive effects of stress exposure. These results (vmPFC), orbital prefrontal cortex (OFC), dorsal anterior cingulate suggest that kappa opioid receptor (KOR) antagonists or low cortex (dACC), striatum, ventral pallidum, and midbrain dopamine efficacy partial agonists may promote stress-resilience in humans neurons are at the center of the circuit associated with reward in and may potentially be useful in treating certain forms of mood general and, in particular addiction. Connectivity between these disorders exacerbated by stressful experience. In rodent models, areas forms a complex neural network that mediates different stress-induced stimulation of dynorphin release produces aversion, aspects of reward processing, that can lead to habit formation. -

OCD and Streptococcal Infections Linked

Child & Adolescent Action Center Kids Newsletter Education/Transition Faith Communities Youth Services Youth Research Depression Awareness First Person Local Contacts Brochures/Factsheets Reading List Internet Resources State/Affiliate Programs OCD and Streptococcal Infections Linked As reported in an article in the Psychiatric Times (December 1997), obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) among children is "remarkably common." According to author Arline Kaplan, the prevalence is one in 100. Focusing on new pharmacological treatment options for children ad adolescents, the article further reported that ".the new drug approval study conducted by Solvay Pharmaceuticals demonstrated that Luvoxr (fluvoxamine) was 'statistically better than placebo for children with OCD.' This was demonstrated by the participant's scores on the Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale and National Institute of Mental Health's Global Obsessive-Compulsive Scale. Of particular interest to parents are the findings of the reports that showed that adverse events among children were about equivalent for two groups; only four patients dropped the study, one on placebo and three on fluvoxamine. What is perhaps even more encouraging ins the work of Susan Swedo, M.D., and Judith Rapoport, M.D., and their colleagues at NIMH who have in their research demonstrated a link between autoimmunity and OCD. According to the Psychiatric Times article, "There is an increasing body of data that suggests there may be a relationship between certain forms of childhood-onset OCD and previous Group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infections. There seem to be a group of children that have early-onset OCD, tic disorder, Sydenham's chorea and family history of tics." Sydenham's chorea is a major manifestation of rheumatic fever and a disorder generally limited to prepubertal children. -

20Th Annual ISMRM Scientific Meeting and Exhibition 2012

20th Annual ISMRM Scientific Meeting and Exhibition 2012 Melbourne, Australia 5-11 May 2012 Table of Contents and Author Index ISBN: 978-1-62276-943-8 ISSN: 1545-4428 Printed from e-media with permission by: Curran Associates, Inc. 57 Morehouse Lane Red Hook, NY 12571 Some format issues inherent in the e-media version may also appear in this print version. Copyright© (2012) by the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine All rights reserved. Printed by Curran Associates, Inc. (2013) For permission requests, please contact the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine at the address below. International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2030 Addison Street, 7th Floor Berkeley, California 94704 Phone: (510) 841-1899 Fax: (510) 841-2340 [email protected] Additional copies of this publication are available from: Curran Associates, Inc. 57 Morehouse Lane Red Hook, NY 12571 USA Phone: 845-758-0400 Fax: 845-758-2634 Email: [email protected] Web: www.proceedings.com TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME 1 0001. - Compressed Sensing Overview........................................................................................................................................................ N/A David Donoho 0002. - Compressed Sensing in MRI................................................................................................................................................................2 Michael Lustig 0003. - Clinical Applications of Compressed Sensing: Introduction: Clinical Opportunities & Barriers to