'*Ffi,Ii .Fhe, CHARMANDPOWEROF TIIE, UPAI{ISADS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Islamic Economic Thinking in the 12Th AH/18Th CE Century with Special Reference to Shah Wali-Allah Al-Dihlawi

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Islamic economic thinking in the 12th AH/18th CE century with special reference to Shah Wali-Allah al-Dihlawi Islahi, Abdul Azim Islamic Economics Institute, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, KSA 2009 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/75432/ MPRA Paper No. 75432, posted 06 Dec 2016 02:58 UTC Abdul Azim Islahi Islamic Economics Research Center King Abdulaziz University Scientific Publising Center King Abdulaziz University http://spc.kau.edu.sa FOREWORD The Islamic Economics Research Center has great pleasure in presenting th Islamic Economic Thinking in the 12th AH (corresponding 18 CE) Century with Special Reference to Shah Wali-Allah al-Dihlawi). The author, Professor Abdul Azim Islahi, is a well-known specialist in the history of Islamic economic thought. In this respect, we have already published his following works: Contributions of Muslim Scholars to th Economic Thought and Analysis up to the 15 Century; Muslim th Economic Thinking and Institutions in the 16 Century, and A Study on th Muslim Economic Thinking in the 17 Century. The present work and the previous series have filled, to an extent, the gap currently existing in the study of the history of Islamic economic thought. In this study, Dr. Islahi has explored the economic ideas of Shehu Uthman dan Fodio of West Africa, a region generally neglected by researchers. He has also investigated the economic ideas of Shaykh Muhammad b. Abd al-Wahhab, who is commonly known as a religious renovator. Perhaps it would be a revelation for many to know that his economic ideas too had a role in his reformative endeavours. -

Reading of the Islam

Muhammad Iqbal Chawla, 1 Robina Shoeb 2 Mughal - Sikh Relations: Revisited Abstract Mughal Empire, attributed to be a Muslim rule, and Sikhism grew side by side in the South Asia; while Zahir-ud-Din Muhammad Babar was founding the Mughal Empire, Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism was expounding a new religious philosophy, Sikhism. Broadly speaking, both religions, Islam and Sikhism, believed in unity, equality, tolerance and love for mankind. These similarities provided a very strong basis of alliance between the two religions. This note of ‘religious acceptance’ of Sikhism was welcomed by the common people, saints and many sage souls among Sikhs and Muslims alike. The Mughal Emperors had by and large showed great generosity to Sikh Gurus except few ones. However, despite these similarities and benevolence of Mughal Emperors, political expediencies and economic imperatives largely kept both the communities estranged and alienated. The relations between Muslims and Sikhs after the death of Akbar, however, underwent many phases and shades. The circumstances that wove the very relationship between the two communities remained obscured under the thick layers of intrigues of the rulers, courtiers, and opportunists. An in-depth study of the background of Mughal-Sikh relations reveals that some political and interest groups including orthodox Muslims and Hindu elites considered friendship between Sikhs and Muslims, a great threat to their positions. These interest groups deliberately created circumstances that eventually developed into unfortunate conflicts between the two communities. Hence the religion was not the main factor that governed the Sikh Muslim relations rather the political, economic and practical exigencies of the time shaped the events that occurred between the two communities. -

PG Syllabus 2011

S.H. INSTITUTE OF ISLAMIC STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF KASHMIR, SRINAGAR Syllabus of Islamic Studies Courses for MA Ist, 2nd, 3rd and 4th semesters 2011 onwards: INSTRUCTIONS a. The Syllabus comprises the courses in Islamic Studies of MA Ist, 2nd 3rd and 4th semesters. b. The syllabus will come into operation from the academic year 2011 for MA Ist, 2nd 3rd and 4th semesters. c. Each Course will contain 100 marks in total. The theory will contain 80 marks and 20 of internal assessment. d. For qualifying each course the candidate has to obtain 32 marks out of 80 and 08 marks out of 20. e. Each paper will be set as per the pattern approved by the University. 1 S. H. Institute of Islamic Studies University of Kashmir, Srinagar REVISED SYLLABUS FOR M.A. ISLAMIC STUDIES (Admission Batch 2011 onwards) 1. M.A. Programme in Islamic Studies shall consist of sixteen courses in total including 08 core and 08 optional/electives with four courses in each Semester (Total Four Semesters) 2. The medium of instruction and examination as in other Social Sciences is English. Students, however, may study standard books on the subject in other languages as well. 3. Regular as well as private students shall have to seek the prior permission from the Institute in case of optional courses. The candidates who have already passed Arabic at Graduation level or Madrasa studies level are not allowed to take up Arabic courses but have to take optional given in the Syllabus. 4. Each course shall carry 100 marks out of which 80 shall be for papers of main semester examination and 20 for continuous assessment in case of regular students. -

Can Spirituality Be Used As a Tool to Withdraw Religious Orthodoxy?

Can spirituality be used as a tool to withdraw religious orthodoxy? Aditya Maurya Jindal Institute of International Affairs Abstract Though spirituality and religion can have mutual elements shared with each other. But when religious orthodoxy takes the position at one end, spiritual enlightenment struggles to take the similar position at another end, as the congregation is visible at various belief-system, due to certain factors. This paper does not look at those factors in details but attempts to draw a parallel between such two convictions. It starts through the interpretation of discourse and encounters between Sufi’s and Nathyogi’s. It also discusses the convergence of Islam and Hinduism through two peaceful movements; Bhakti and Sufism, how they rejected the sectarian hierarchy and promoted the path of enlightenment, liberation and reason by granting benefit of theological doubt. It argues by positing an argument, if in 21st century, there existed such movements; spirituality might have curtailed some amount of religious orthodoxy witnessed today. Keywords – religious orthodoxy, enlightenment, spirituality Spirituality: Any Definition? It is not fair to pin down a specific definition of spirituality, as spirituality in itself is an evolutionary process; scholar’s practitioners, observers about spirituality, are defining various notions. If spirituality is considered as an internal quest of one’s existence, the ontology of self; there exists an osmotic boundary between spirituality and religion. On the contrary if spirituality is externalized, then it takes the position of a religion in a form of movement, ritual, or belief system. Apparently, religion has a set of rules, schema and principles associated to it. -

Citation of Miracles in Mysticism and Preaching of Islam: Sub-Continental Perspective Jan – June 2021

Citation of Miracles in Mysticism and Preaching of Islam: Sub-continental Perspective Jan – June 2021 Citation of Miracles in Mysticism and Preaching of Islam: Sub-continental Perspective Dr. Anwarullah* Dr. Imtiaz Ahmed** Bilal Hussain*** Sarfraz Ali**** Abstract Some subcontinent research scholars deny the miracles (Karamaat) of the mystics (Sufi Saints). They think that these miracles (Karamaat) are actually the stories that their disciples fabricated in zeal and then became popular among the masses. The biographers of the saints also cited these stories in their books. In their opinion, these saints did not perform any significant efforts of preaching the religion, because if they had performed any effort to preach the religion they have been mentioned in detail that arose during the preaching of the religion. In this research paper, the arguments of various scholars are analyzed in their scientific and historical perspectives. This research paper discusses in detail. The style of Sufi preaching and its reality. This research paper will be a great help for the incoming researchers in exploring various new aspects of the affairs of the Saints, religious and the intellectual history of the Indo-Pak-subcontinent. Keywords: Miracles, Mystics, Sufi preaching, Subcontinent, Excessive Introduction Miracles (Karamaat) refer to the supernatural deeds of the saints commanded by the almighty Allah through his saints for their protection (Urdu DairaMoarif e Islamia, 1978). Hazrat Ali Hajwari is known as Data Ganj Bakhsh describes a miracle as the reality describing proof of sainthood. And a liar cannot do so. Well, the symbols of falsehood and wrongdoings only will be reflected by a liar. -

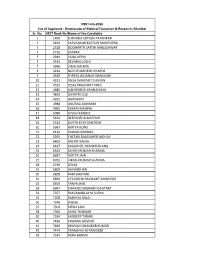

Sr. No. NEET Rank No.Name of the Candidate 1 1406

NEET-UG-2016 List of Applicant - Directorate of Medical Education & Research, Mumbai Sr. No. NEET Rank No.Name of the Candidate 1 1406 SUKHADA SUYASH PATANKAR 2 2164 SARVANKAR KASTURI MAHENDRA 3 2528 SIDDHARTH SATISH BABLESHWAR 4 2716 SAMIRA 5 2949 SANA AFRIN 6 3535 DEVANGI JOSHI 7 3966 VIDHI DALMIA 8 4234 NUPUR MAHESH KHARDE 9 4320 SHREYA GAJANAN NAMJOSHI 10 4321 ANSH SHRIKANT CHAVAN 11 4535 TEJAS PRASHANT PATIL 12 4685 AISHWARYA YANNAMANI 13 4839 GAYATRI LELE 14 4923 HARSHANT 15 4988 ANURAG ABHISHEK 16 4995 KESHAV NAGPAL 17 5080 AYUSH KANDOI 18 5454 DEEPANSHA MATHUR 19 5524 GUPTA EKTA SANTOSH 20 5967 ADITYA KOHLI 21 6134 PAWAN SHARMA 22 6265 CHETAN BALASAHEB JADHAV 23 6403 ARCHIT KALRA 24 6427 KALBANDE AKANKSHA ANIL 25 6543 ASHISH KUMAR SHARMA 26 6697 ADITYA JAIN 27 6702 VIKASH KUMAR SHARMA 28 6749 ZENAB 29 6800 JAIVARDHAN 30 6828 RAM BHUTANI 31 6894 UTKARSHA RAVIKANT ANWEKAR 32 6919 TANYA JAIN 33 6997 CHHAJED SAURABH GAUTAM 34 7077 SRAVANAM JAYA SURYA 35 7208 RADHIKA BAJAJ 36 7246 SNEHA 37 7304 RITIKA JAIN 38 7306 AKHIL THAKKAR 39 7334 SANDEEP TIWARI 40 7426 KRISHNA GOVIND 41 7460 BHAVANI SHANKAR KUMAR 42 7474 PRANAYAK M PANICKER 43 7545 AENA BANSAL NEET-UG-2016 List of Applicant - Directorate of Medical Education & Research, Mumbai Sr. No. NEET Rank No.Name of the Candidate 44 7561 JAYA SRIVASTAVA 45 7562 SHWETA MENON 46 7595 BHOM RAJ 47 7615 BHARAT KUMAR 48 7802 MURLI DHAR 49 7826 DIVYA CHUTANI 50 7965 SHUBHANGI GOURAHA 51 7988 NIKITA PALIWAL 52 8008 ASHID ALI SHEIKH 53 8058 MALAVIKA PRADEEP 54 8073 RISHAB SHINDE 55 8083 VEDANTI -

Religious Poetry of an Indian Muslim Saint: Sheikh Muhammadbaba

Deák, Dušan. 2020. Religious poetry of an Indian Muslim saint: Sheikh Muhammadbaba. Materials Axis Mundi 15 (1): 45-49. Religious poetry of an Indian Muslim saint: Sheikh Muhammadbaba DuŠan Deák Department of Comparative Religion, Faculty of Arts Comenius University in Bratislava Since the last centuries of the frst millennium India the only Muslim poet hailing from Maharashtra among saw a rise of the voices that expressed the religious ideas the host of other saint-poets. Being ofen a stern critic and experiences in the vernaculars. Te bearers of these of the pre-modern Maharashtrian society has also won voices, men and women today recognized as holy, were him a recognition of being an incarnation of Northern ofen self-made poets, or better singers and performers Indian sant3 Kabir. However, over the four centuries of religious poetry who expressed their inner thoughts the Sheikh became particularly dear to Maharashtrian and devotion with rare intensity thereby earning the Vaishnavas – Varkaris, the devotees of the Viththala recognition of the surrounding public. Tey came from from Pandharpur. With Varkaris he shared not only the the various social circles and could be also of diferent ways of expressing devotion in personal and emotional religious denomination. Teir poetical compositions, terms, but also the myths related to Pandharpur, Vith- prevalently, but not exclusively, clad in the Vaishnava thal, as well as to the other saint-poets to whose com- idiom, emphasized rather a personal than organized pany he has been ofen placed in the hagiographic nar- engagement with the religion. Not seldom the saint-po- ratives. Indeed, the religion of Varkaris, who form the ets therefore became critics of then contemporary re- mainstream religious movement in whole Maharashtra ligiosity and social organization and till today enjoy has been fed on the saint-poets and their songs. -

Unclaimed Deposit 2014

Details of the Branch DETAILS OF THE DEPOSITOR/BENEFICIARIYOF THE INSTRUMANT NAME AND ADDRESS OF DEPOSITORS DETAILS OF THE ACCOUNT DETAILS OF THE INSTRUMENT Transaction Federal/P rovincial Last date of Name of Province (FED/PR deposit or in which account Instrume O) Rate Account Type Currency Rate FCS Rate of withdrawal opened/instrume Name of the nt Type In case of applied Amount Eqv.PKR Nature of Deposit ( e.g Current, (USD,EUR,G Type Contract PKR (DD-MON- Code Name nt payable CNIC No/ Passport No Name Address Account Number applicant/ (DD,PO, Instrument NO Date of issue instrumen date Outstandi surrender (LCY,UFZ,FZ) Saving, Fixed BP,AED,JPY, (MTM,FC No (if conversio YYYY) Purchaser FDD,TDR t (DD-MON- ng ed or any other) CHF) SR) any) n , CO) favouring YYYY) the Governm ent 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 PRIX 1 Main Branch Lahore PB Dir.Livestock Quetta MULTAN ROAD, LAHORE. 54500 LCY 02011425198 CD-MISC PHARMACEUTICA TDR 0000000189 06-Jun-04 PKR 500 12-Dec-04 M/S 1 Main Branch Lahore PB MOHAMMAD YUSUF / 1057-01 LCY CD-MISC PKR 34000 22-Mar-04 1 Main Branch Lahore PB BHATTI EXPORT (PVT) LTD M/S BHATTI EXPORT (PVT) LTD M/SLAHORE LCY 2011423493 CURR PKR 1184.74 10-Apr-04 1 Main Branch Lahore PB ABDUL RAHMAN QURESHI MR ABDUL RAHMAN QURESHI MR LCY 2011426340 CURR PKR 156 04-Jan-04 1 Main Branch Lahore PB HAZARA MINERAL & CRUSHING IND HAZARA MINERAL & CRUSHING INDSTREET NO.3LAHORE LCY 2011431603 CURR PKR 2764.85 30-Dec-04 "WORLD TRADE MANAGEMENT M/SSUNSET LANE 1 Main Branch Lahore PB WORLD TRADE MANAGEMENT M/S LCY 2011455219 CURR PKR 75 19-Mar-04 NO.4,PHASE 11 EXTENTION D.H.A KARACHI " "BASFA INDUSTRIES (PVT) LTD.FEROZE PUR 1 Main Branch Lahore PB 0301754-7 BASFA INDUSTRIES (PVT) LTD. -

Indian Soldiers Died in Italy During World War II: 1943-45

Indian Soldiers died in Italy during World War II: 1943-45 ANCONA WAR CEMETERY, Italy Pioneer ABDUL AZIZ , Indian Pioneer Corps. Gurdaspur, Grave Ref. V. B. 1. Sepoy ABDUL JABAR , 10th Baluch Regiment. Hazara, Grave Ref. V. B. 4. Sepoy ABDUL RAHIM , 11th Indian Inf. Bde. Jullundur, Grave Ref. V. D. 6. Rifleman AITA BAHADUR LIMBU , 10th Gurkha Rifles,Dhankuta, Grave Ref. VII. D. 5. Sepoy ALI GAUHAR , 11th Sikh Regiment. Rawalpindi, Grave Ref. V. D. 4. Sepoy ALI MUHAMMAD , 11th Sikh Regiment, Jhelum, Grave Ref. V. B. 6. Cook ALLAH RAKHA , Indian General Service Corps,Rawalpindi, Grave Ref. III. L. 16. Sepoy ALTAF KHAN , Royal Indian Army Service Corps,Alwar, Grave Ref. V. D. 5. Rifleman ANAND KHATTRI, 2nd King Edward VII's Own Gurkha Rifles (The Sirmoor Rifles). Grave Ref. VII. B. 7. Sapper ARUMUGAM , 12 Field Coy., Queen Victoria's Own Madras Sappers and Miners. Nanjakalikurichi. Grave Ref. V. B. 2. Rifleman BAL BAHADUR ROKA, 6th Gurkha Rifles. , Grave Ref. VII. B. 5. Rifleman BAL BAHADUR THAPA, 8th Gurkha Rifles.,Tanhu, , Grave Ref. VII. D. 8. Rifleman BHAGTA SHER LIMBU , 7th Gurkha Rifles, Dhankuta, ,Grave Ref. VII. F. 1. Rifleman BHAWAN SING THAPA , 4th Prince of Wales' Own Gurkha Rifles. Gahrung, , Grave Ref. VII. C. 4. Rifleman BHIM BAHADUR CHHETRI , 6th Gurkha Rifles. Gorkha, Grave Ref. VII. C. 5. Rifleman BHUPAL THAPA , 2nd King Edward VII's Own Gurkha Rifles (The Sirmoor Rifles). Sallyan, Grave Ref. VII. E. 4. Rifleman BIR BAHADUR SUNWAR , 7th Gurkha Rifles. Ramechhap, Grave Ref. VII. F. 8. Rifleman BIR BAHADUR THAPA, 8th Gurkha Rifles, Palpa, Grave Ref. -

List of Mbbs Graduates for the Year 1997

KING EDWARD MEDICAL UNIVERSITY, LAHORE LIST OF MBBS GRADATES 1865 – 1996 1865 1873 65. Jallal Oddeen 1. John Andrews 31. Thakur Das 2. Brij Lal Ghose 32. Ghulam Nabi 1878 3. Cheytun Shah 33. Nihal Singh 66. Jagandro Nath Mukerji 4. Radha Kishan 34. Ganga Singh 67. Bishan Das 5. Muhammad Ali 35. Ammel Shah 68. Hira Lal 6. Muhammad Hussain 36. Brij Lal 69. Bhagat Ram 7. Sahib Ditta 37. Dari Mal 70. Atar Chand 8. Bhowani Das 38. Fazi Qodeen 71. Nathu Mal 9. Jaswant Roy 39. Sobha Ram 72. Kishan Chandra 10. Haran Chander Banerji 73. Duni Chand Raj 1874 74. Ata Muhammad 1868 40. Sobhan Ali 75. Charan Singh 76. Manohar Parshad 11. Fateh Singh 41. Jowahir Singh 12. Natha Mal 42. Lachman Das 1879 13. Ram Rich Pall 43. Dooni Chand 14. Bhagwan Das 44. Kali Nath Roy 77. Sada Nand 15. Mul Chand 45. Booray Khan 78. Mohandro Nath Ohdidar 16. Mehtab singh 46. Jodh Singh 79. Jai Singh 47. Munna Lal 80. Khazan Chand 48. Mehr Chand 81. Dowlat Ram 1869 49. Jowala Sahai 82. Jai Krishan Das 17. Taboo Singh 50. Gangi Ram 83. Perama Nand 18. Utum Singh 52. Devi Datta 84. Ralia Singh 19. Chany Mal 85. Jagan Nath 20. Esur Das 1875 86. Manohar Lal 21. Chunnoo Lal 53. Ram Kishan 87. Jawala Prasad 54. Kashi Ram 1870 55. Alla Ditta 1880 22. Gokal Chand 56. Bhagat Ram 88. Rasray Bhatacharji 57. Gobind Ram 89. Hira Lal Chatterji 90. Iktadar-ud-Din 1871 1876 91. Nanak Chand 23. Urjan Das 58. -

Philosophy in Pakistan

Cultural Heritage and Contemporary Change Series IIA. Islam. Volume 3 Philosophy in Pakistan edited by Naeem Ahmad The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy Copyright © 1998 by The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy Gibbons Hall B-20 620 Michigan Avenue, NE Washington, D.C. 20064 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Philosophy in Pakistan /edited by Naeem Ahmad. p.cm. – (Cultural heritage and contemporary change. Series IIA Islam; vol. 3) Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Philosophy, Pakistan. 2. Islam and Philosophy. 3. Religion. I Naeem Ahmad, 1940-. II. Series. B5126 P84 1997 97-26581 181’.15—dc21 CIP ISBN 1-56518-108-5 (pbk.) Contents Preface vii Naeem Ahmad Introduction 1 George F. McLean Part I Philosophy as a Search for Unity in the Transcendent Chapter I. The Philosophical Interpretation of History 9 M. M. Sharif Chapter II. One God, One World, One Humanity 21 Khalifa Abdul Hakim Chapter III. Iqbal’s ‘Preface’ to His Lectures on the Reconstruction 41 of Religious Thought in Islam Q. M. Aslam Chapter IV. A Case for World Philosophy: My Intellectual Story 47 C. A. Qadir Chapter V. How I See Philosophy 75 Intisar-ul-Haq Chapter VI. God, Universe and Man 89 Muhammad Hanif Nadvi Chapter VII. Iqbal on the Material and Spiritual Future of Humanity 97 Javid Iqbal Part II Classical Islamic Philosophy and Metaphysics Chapter VIII. Philosophy of Religion: Its Meaning and Scope 115 M. Saeed Sheikh Chapter IX. Function of Muslim Philosophy 131 Abdul Khaliq Chapter X. -

The Causes of Religious Wars: Holy Nations, Sacred Spaces, and Religious Revolutions

The Causes of Religious Wars: Holy Nations, Sacred Spaces, and Religious Revolutions By Heather Selma Gregg Master’s of Theological Studies (1998) Harvard Divinity School B.A., Cultural Anthropology (1993) University of California at Santa Cruz Submitted to the Department of Political Science In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology February 2004 Copyright 2003 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All Rights Reserved 1 2 The Causes of Religious Wars: Holy Nations, Sacred Spaces, and Religious Revolutions by Heather Selma Gregg Submitted to the Department of Political Science on October 27, 2003 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science Abstract In the wake of September 11th, policy analysts, journalists, and academics have tried to make sense of the rise of militant Islam, particularly its role as a motivating and legitimating force for violence against the US. The unwritten assumption is that there is something about Islam that makes it bloodier and more violence-prone than other religions. This dissertation seeks to investigate this assertion by considering incidents of Islamically motivated terrorism, violence, and war, and comparing them to examples of Christian, Jewish, Buddhist and Hindu bellicosity. In doing so, it aims to evaluate if religious violence is primarily the product of beliefs, doctrine and scripture, or if religious violence is the result of other factors