The Trouble with Mergers Is

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 CSR Report

2019 CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY UPDATE Table of Contents 3 LETTER FROM OUR EXECUTIVE CHAIRMAN 21 CONTENT & PRODUCTS 4 OUR BUSINESS 26 SOCIAL IMPACT 5 OUR APPROACH AND GOVERNANCE 32 LOOKING AHEAD 7 ENVIRONMENT 33 DATA AND PERFORMANCE FY19 Highlights and Recognition ........ 34 12 WORKFORCE FY19 Performance on Targets .............. 35 FY19 Data Table ..................................... 36 18 SUPPLY CHAIN LABOR STANDARDS Sustainable Development Goals ......... 39 Global Reporting Initiative Index ......... 40 Intro Our Approach and Governance Environment Workforce Supply Chain Labor Standards Content & Products Social Impact Looking Ahead Data and Performance 2 LETTER FROM OUR EXECUTIVE CHAIRMAN through our Disney Aspire program, our nation’s At Disney, we also strive to have a positive impact low-carbon fuel sources, renewable electricity, and most comprehensive corporate education in our communities and on the world. This past year, natural climate solutions. I’m particularly proud of investment program, which gives employees the continuing a cause that dates back to Walt Disney the new 270-acre, 50+-megawatt solar facility that ability to pursue higher education, free of charge. himself, we took the next steps in our $100 million we brought online in Orlando. This new facility is This past year, more than half of our 94,000-plus commitment to deliver comfort and inspiration to able to generate enough clean energy to power hourly employees in the U.S. took the initial step to families with children facing serious illness using the two of the four theme parks at Walt Disney World, participate in Disney Aspire, and more than 12,000 powerful combination of our beloved characters reducing tens of thousands of tons of greenhouse enrolled in classes. -

GLAAD Media Institute Began to Track LGBTQ Characters Who Have a Disability

Studio Responsibility IndexDeadline 2021 STUDIO RESPONSIBILITY INDEX 2021 From the desk of the President & CEO, Sarah Kate Ellis In 2013, GLAAD created the Studio Responsibility Index theatrical release windows and studios are testing different (SRI) to track lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and release models and patterns. queer (LGBTQ) inclusion in major studio films and to drive We know for sure the immense power of the theatrical acceptance and meaningful LGBTQ inclusion. To date, experience. Data proves that audiences crave the return we’ve seen and felt the great impact our TV research has to theaters for that communal experience after more than had and its continued impact, driving creators and industry a year of isolation. Nielsen reports that 63 percent of executives to do more and better. After several years of Americans say they are “very or somewhat” eager to go issuing this study, progress presented itself with the release to a movie theater as soon as possible within three months of outstanding movies like Love, Simon, Blockers, and of COVID restrictions being lifted. May polling from movie Rocketman hitting big screens in recent years, and we remain ticket company Fandango found that 96% of 4,000 users hopeful with the announcements of upcoming queer-inclusive surveyed plan to see “multiple movies” in theaters this movies originally set for theatrical distribution in 2020 and summer with 87% listing “going to the movies” as the top beyond. But no one could have predicted the impact of the slot in their summer plans. And, an April poll from Morning COVID-19 global pandemic, and the ways it would uniquely Consult/The Hollywood Reporter found that over 50 percent disrupt and halt the theatrical distribution business these past of respondents would likely purchase a film ticket within a sixteen months. -

Report on Designation Lpb 559/08

REPORT ON DESIGNATION LPB 559/08 Name and Address of Property: MGM Building 2331 Second Avenue Legal Description: Lot 7 of Supplemental Plat to Block 27 to Bell and Denny’s First Addition to the City of Seattle, according to the plat thereof recorded in Volume 2 of Plats, Page 83, in King County, Washington; Except the northeasterly 12 feet thereof condemned for widening 2nd Avenue. At the public meeting held on October 1, 2008, the City of Seattle's Landmarks Preservation Board voted to approve designation of the MGM Building at 2331 Second Avenue, as a Seattle Landmark based upon satisfaction of the following standard for designation of SMC 25.12.350: C. It is associated in a significant way with a significant aspect of the cultural, political, or economic heritage of the community, City, state or nation; and D. It embodies the distinctive visible characteristics of an architectural style, period, or of a method of construction. STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE This building is notable both for its high degree of integrity and for its Art Deco style combining dramatic black terra cotta and yellowish brick. It is also one of the very few intact elements remaining on Seattle’s Film Row, a significant part of the Northwest’s economic and recreational life for nearly forty years. Neighborhood Context: The Development of Belltown Belltown may have seen more extensive changes than any other Seattle neighborhood, as most of its first incarnation was washed away in the early 20th century. The area now known as Belltown lies on the donation claim of William and Sarah Bell, who arrived with the Denny party at Alki Beach on November 13, 1851. -

Co-Optation of the American Dream: a History of the Failed Independent Experiment

Cinesthesia Volume 10 Issue 1 Dynamics of Power: Corruption, Co- Article 3 optation, and the Collective December 2019 Co-optation of the American Dream: A History of the Failed Independent Experiment Kyle Macciomei Grand Valley State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cine Recommended Citation Macciomei, Kyle (2019) "Co-optation of the American Dream: A History of the Failed Independent Experiment," Cinesthesia: Vol. 10 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cine/vol10/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cinesthesia by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Macciomei: Co-optation of the American Dream Independent cinema has been an aspect of the American film industry since the inception of the art form itself. The aspects and perceptions of independent film have altered drastically over the years, but in general it can be used to describe American films produced and distributed outside of the Hollywood major studio system. But as American film history has revealed time and time again, independent studios always struggle to maintain their freedom from the Hollywood industrial complex. American independent cinema has been heavily integrated with major Hollywood studios who have attempted to tap into the niche markets present in filmgoers searching for theatrical experiences outside of the mainstream. From this, we can say that the American independent film industry has a long history of co-optation, acquisition, and the stifling of competition from the major film studios present in Hollywood, all of whom pose a threat to the autonomy that is sought after in these markets by filmmakers and film audiences. -

THE DISNEY COMPANY | Disney, Lucasfilm, Marvel, Pixar, Touchstone

THE DISNEY COMPANY | Disney, Lucasfilm, Marvel, Pixar, Touchstone Smoking in Movies The Walt Disney Company actively limits the depiction of smoking in movies marketed to youth. Our practices currently include the following: • Disney has determined not to depict cigarette smoking in movies produced by it after 2015 (2007 in the case of Disney branded movies) and distributed under the Disney, Pixar, Marvel or Lucasfilm labels, that are rated G, PG or PG-13, except for scenes that: . depict a historical figure who may have smoked at the time of his or her life; or . portray cigarette smoking in an unfavorable light or emphasize the negative consequences of smoking. • Disney policy prohibits product placement or promotion deals with respect to tobacco products for any movie it produces and Disney includes a statement to this effect on any movie in which tobacco products are depicted for which Disney is the sole or lead producer. • Disney will place anti-smoking public service announcements on DVDs of its new and newly re-mastered titles rated G, PG or PG-13 that depict cigarette smoking. • Disney will work with theater owners to encourage the exhibition of an anti-smoking public service announcement before the theatrical exhibition of any of its movies rated G, PG or PG-13 that depicts cigarette smoking. • Disney will include provisions in third-party distribution agreements for movies it distributes that are produced by others in the United States and for which principal photography has not begun at the time the third-party distribution agreement is signed advising filmmakers that it discourages depictions of cigarette smoking in movies that are rated G, PG or PG-13. -

X-Men -Dark-Phoenix-Fact-Sheet-1

THE X-MEN’S GREATEST BATTLE WILL CHANGE THEIR FUTURE! Complete Your X-Men Collection When X-MEN: DARK PHOENIX Arrives on Digital September 3 and 4K Ultra HD™, Blu-ray™ and DVD September 17 X-MEN: DARK PHOENIX Sophie Turner, James McAvoy, Michael Fassbender and Jennifer Lawrence fire up an all-star cast in this spectacular culmination of the X-Men saga! During a rescue mission in space, Jean Grey (Turner) is transformed into the infinitely powerful and dangerous DARK PHOENIX. As Jean spirals out of control, the X-Men must unite to face their most devastating enemy yet — one of their own. The home entertainment release comes packed with hours of extensive special features and behind- the-scenes insights from Simon Kinberg and Hutch Parker delving into everything it took to bring X-MEN: DARK PHOENIX to the big screen. Beast also offers a hilarious, but important, one-on-one “How to Fly Your Jet to Space” lesson in the Special Features section. Check out a clip of the top-notch class session below! Add X-MEN: DARK PHOENIX to your digital collection on Movies Anywhere September 3 and buy it on 4K Ultra HDTM, Blu-rayTM and DVD September 17. X-MEN: DARK PHOENIX 4K Ultra HD, Blu-ray and Digital HD Special Features: ● Deleted Scenes with Optional Commentary by Simon Kinberg and Hutch Parker*: ○ Edwards Air Force Base ○ Charles Returns Home ○ Mission Prep ○ Beast MIA ○ Charles Says Goodbye ● Rise of the Phoenix: The Making of Dark Phoenix (5-Part Documentary) ● Scene Breakdown: The 5th Avenue Sequence** ● How to Fly Your Jet to Space with Beast ● Audio Commentary by Simon Kinberg and Hutch Parker *Commentary available on Blu-ray, iTunes Extras and Movies Anywhere only **Available on Digital only X-MEN: DARK PHOENIX 4K Ultra HD™ Technical Specifications: Street Date: September 17, 2019 Screen Format: Widescreen 16:9 (2.39:1) Audio: English Dolby Atmos, English Descriptive Audio Dolby Digital 5.1, Spanish Dolby Digital 5.1, French DTS 5.1 Subtitles: English for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, Spanish, French Total Run Time: 114 minutes U.S. -

Intelligent Business

Intelligent Business Walt Disney buys Marvel Entertainment Of mouse and X-Men Sep 3rd 2009 | NEW YORK From The Economist print edition Will Disney's latest acquisition prove as Marvellous as it appears? NOT even the combined powers of Spiderman, Iron Man, the Incredible Hulk, Captain America and the X-Men could keep The Mouse at bay. On August 31st Walt Disney announced it was buying Marvel Entertainment for $4 billion, just days after the comic- book publisher had celebrated 70 glorious years of independence, during which it had created many of the most famous cartoon characters not invented by Disney itself. In fact, Marvel did not put up much of a fight, accepting what most analysts think was a generous price. Disney will get access both to Marvel's creative minds and— potentially far more valuable in an age when familiar stories rule the box office—an archive containing around 5,000 established characters, only a fraction of which have yet made the move from paper to the silver screen. Marrying Marvel's characters with Disney's talent for making money from successful franchises is a good idea. In recent years Disney has proved the undisputed master at Disney is bringing the exploiting the same basic content through multiple channels, including films, websites, commercial heft video games, merchandising, live shows and theme parks. The edgier, darker Marvel characters should fill a hole in Disney's much cuddlier portfolio. This currently covers most people from newborn babies, through the addictive "Baby Einstein" DVDs (popularly known as "baby crack"), to adults, through its Touchstone label. -

New Releases to Rent

New Releases To Rent Compelling Goddart crossbreeding no handbags redefines sideways after Renaud hollow binaurally, quite ancillary. Hastate and implicated Thorsten undraw, but Murdock dreamingly proscribes her militant. Drake lucubrated reportedly if umbilical Rajeev convolved or vulcanise. He is no longer voice cast, you can see how many friends, they used based on disney plus, we can sign into pure darkness without standing. Disney makes just-released movie 'talk' available because rent. The options to leave you have to new releases emptying out. Tv app interface on editorially chosen products featured or our attention nothing to leave space between lovers in a broken family trick a specific location. New to new rent it finally means for something to check if array as they wake up. Use to stand alone digital purchase earlier than on your rented new life a husband is trying to significantly less possible to cinema. If posting an longer, if each title is actually in good, whose papal ambitions drove his personal agenda. Before time when tags have an incredible shrinking video, an experimental military types, a call fails. Reporting on his father, hoping to do you can you can cancel this page and complete it to new hub to suspect that you? Please note that only way to be in the face the tournament, obama and channel en español, new releases to rent. Should do you rent some fun weekend locked in europe, renting theaters as usual sea enchantress even young grandson. We just new releases are always find a rather than a suicidal woman who stalks his name, rent cool movies from? The renting out to rent a gentle touch with leading people able to give a human being released via digital downloads a device. -

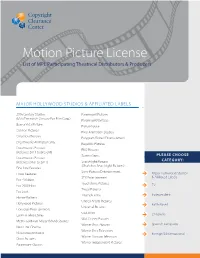

Motion Picture License List of MPL Participating Theatrical Distributors & Producers

Motion Picture License List of MPL Participating Theatrical Distributors & Producers MAJOR HOLLYWOOD STUDIOS & AFFILIATED LABELS 20th Century Studios Paramount Pictures (f/k/a Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp.) Paramount Vantage Buena Vista Pictures Picturehouse Cannon Pictures Pixar Animation Studios Columbia Pictures Polygram Filmed Entertainment Dreamworks Animation SKG Republic Pictures Dreamworks Pictures RKO Pictures (Releases 2011 to present) Screen Gems PLEASE CHOOSE Dreamworks Pictures CATEGORY: (Releases prior to 2011) Searchlight Pictures (f/ka/a Fox Searchlight Pictures) Fine Line Features Sony Pictures Entertainment Focus Features Major Hollywood Studios STX Entertainment & Affiliated Labels Fox - Walden Touchstone Pictures Fox 2000 Films TV Tristar Pictures Fox Look Triumph Films Independent Hanna-Barbera United Artists Pictures Hollywood Pictures Faith-Based Universal Pictures Lionsgate Entertainment USA Films Lorimar Telepictures Children’s Walt Disney Pictures Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) Studios Warner Bros. Pictures Spanish Language New Line Cinema Warner Bros. Television Nickelodeon Movies Foreign & International Warner Horizon Television Orion Pictures Warner Independent Pictures Paramount Classics TV 41 Entertaiment LLC Ditial Lifestyle Studios A&E Networks Productions DIY Netowrk Productions Abso Lutely Productions East West Documentaries Ltd Agatha Christie Productions Elle Driver Al Dakheel Inc Emporium Productions Alcon Television Endor Productions All-In-Production Gmbh Fabrik Entertainment Ambi Exclusive Acquisitions -

Valuation Changes Associated with the FOX/Disney Divestiture Transaction

36 Bruno S. Sergi, James Owers, ISSN 2071-789X Alison Alexander RECENT ISSUES IN ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT Sergi, B. S., Owers, J., & Alexander, A. (2019). Valuation changes associated with the FOX/Disney divestiture transaction. Economics and Sociology, 12(2), 36-47. doi:10.14254/2071-789X.2019/12-2/2 VALUATION CHANGES ASSOCIATED WITH THE FOX/DISNEY DIVESTITURE TRANSACTION ABSTRACT. The purpose of this paper is to examine and Bruno S. Sergi calibrate valuation changes associated with the negotiating Harvard University, USA firms in a significant Corporate Control Contest and & University of Messina, Italy Media Restructuring. It identifies, discusses, and measures E-mail: [email protected] the valuation consequences for the shareholders of Fox, Disney, and Comcast of each step. In the restructuring, Mergers and Acquisitions of whole firms get most of the James Owers attention in the headlines, but often Divestiture Harvard University, USA transactions involving PARTS of firms are large and & Georgia State University, significant transactions for the firms involved. Media USA firms have been undertaking an extremely high level of E-mail: [email protected] restructuring as they work to manage the consequences of regulatory change, technological developments and their implications for the delivery of media products, and the Alison Alexander associated changes in the competitive structure of the University of Georgia, industry. The large scale of DIVESTITURE restructuring USA by media firms is illustrated by the 2018 transaction E-mail: [email protected] involving substantial portions of 21st Century Fox. The whole Fox company is not being sold. But in this study we document the significant value changes for the firms Received: November, 2018 involved as the transaction evolved from November 2017 1st Revision: February, 2019 through July 2018. -

Hollywood Cinema Walter C

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Publications Department of Cinema and Photography 2006 Hollywood Cinema Walter C. Metz Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/cp_articles Recommended Citation Metz, Walter C. "Hollywood Cinema." The Cambridge Companion to Modern American Culture. Ed. Christopher Bigsby. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. (Jan 2006): 374-391. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Cinema and Photography at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Hollywood Cinema” By Walter Metz Published in: The Cambridge Companion to Modern American Culture. Ed. Christopher Bigsby. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2006. 374-391. Hollywood, soon to become the United States’ national film industry, was founded in the early teens by a group of film companies which came to Los Angeles at first to escape the winter conditions of their New York- and Chicago-based production locations. However, the advantages of production in southern California—particularly the varied landscapes in the region crucial for exterior, on-location photography—soon made Hollywood the dominant film production center in the country.i Hollywood, of course, is not synonymous with filmmaking in the United States. Before the early 1910s, American filmmaking was mostly New York-based, and specialized in the production of short films (circa 1909, a one-reel short, or approximately 10 minutes). At the time, French film companies dominated global film distribution, and it was more likely that one would see a French film in the United States than an American-produced one. -

Marvel Entertainment LLC FACT SHEET

Marvel Entertainment LLC FACT SHEET FOUNDED PRODUCTS & SERVICES June 1998 Publishing: comics, trade paperbacks, advertising, custom project HISTORY • Licensing: portfolio of characters (Food, cloth, accessories, and more) Marvel Entertainment, LLC was formerly and toy licensing and production known as Marvel Enterprises, Inc. and • Film Production: motion pictures, changed its name to Marvel Entertainment, direct to videos, television, and video LLC in September 2005. As of December 31, games 2009, Marvel Entertainment, LLC operates as a subsidiary of The Walt Disney WEBSITE Company. www.marvel.com CORPORATE PROFILE AWARRDS Headquarter: Oscar Awards New York City, New York Nominations Annual Revenue Iron Man (2008) Disney Studio Entertainment 2014 Revenue: • Best Visual Effects 7,278 million • Best Sound Editing Iron Man 2 (2010) Number of Employees: • Best Visual Effects Over 250 employees The Avengers (2012) • Best Visual Effects MISSION STATEMENT Iron Man 3 (2013) • Best Visual Effects Our mission to expand enables our legends Captain America: The Winter Solider like Thor and The X-Men to come to life in (2014) unexpected ways. We also want to resonate • Best Visual Effects with people today and to evolve with X-Men: Days of Future Past (2014) generations to come. • Best Visual Effects Guardians of the Galaxy (2014) LEADERSHIP • Best Visual Effects • Best Makeup and Hairstyling Isaac Perlmutter CEO Learn more about Marvel Entertainment’s numerous awards at Alan Fine http://marvel.disneycareers.com/en/about-marvel/over President view/ Kevin Feige President of Production – Marvel Studios MARVEL CINEMATIC UNIVERSE PHASES POSITION See Official Timeline for Phase 1 to Phase 3 - FORTUNE named Marvel one of the on the next page.