Quintus in Britannia: Visiting Roman Britain with the Cambridge Latin Course

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cambridge Latin Course Unit 4 University of Cambridge School Classics Project Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-66082-3 – North American Cambridge Latin Course Unit 4 University of Cambridge School Classics Project Frontmatter More information Cambridge Latin Course Unit 4 Teacher's Manual FIFTH EDITION © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-66082-3 – North American Cambridge Latin Course Unit 4 University of Cambridge School Classics Project Frontmatter More information 32 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY10013-2473, USA Cambridge University Press is part of the University of Cambridge. It furthers the University’s mission by disseminating knowledge in the pursuit of education, learning and research at the highest international levels of excellence. Information on this title: education.cambridge.org The Cambridge Latin Course is an outcome of work jointly commissioned by the Cambridge School Classics Project and the Schools Council © Schools Council 1970, 1982 (succeeded by the School Curriculum Development Committee © SCDC Publications 1988). © University of Cambridge School Classics Project 2001, 2015 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 1970 Second edition 1982 Third edition 1988 Fourth edition 2001 Fifth edition 2015 Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available isbn 978-1-107-66082-3 Cover image, © The Trustees of The British Museum; background andras_csontos / © Shutterstock Cambridge University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this publication, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. -

Two Studies on Roman London. Part B: Population Decline and Ritual Landscapes in Antonine London

Two Studies on Roman London. Part B: population decline and ritual landscapes in Antonine London In this paper I turn my attention to the changes that took place in London in the mid to late second century. Until recently the prevailing orthodoxy amongst students of Roman London was that the settlement suffered a major population decline in this period. Recent excavations have shown that not all properties were blighted by abandonment or neglect, and this has encouraged some to suggest that the evidence for decline may have been exaggerated.1 Here I wish to restate the case for a significant decline in housing density in the period circa AD 160, but also draw attention to evidence for this being a period of increased investment in the architecture of religion and ceremony. New discoveries of temple complexes have considerably improved our ability to describe London’s evolving ritual landscape. This evidence allows for the speculative reconstruction of the main processional routes through the city. It also shows that the main investment in ceremonial architecture took place at the very time that London’s population was entering a period of rapid decline. We are therefore faced with two puzzling developments: why were parts of London emptied of houses in the middle second century, and why was this contraction accompanied by increased spending on religious architecture? This apparent contradiction merits detailed consideration. The causes of the changes of this period have been much debated, with most emphasis given to the economic and political factors that reduced London’s importance in late antiquity. These arguments remain valid, but here I wish to return to the suggestion that the Antonine plague, also known as the plague of Galen, may have been instrumental in setting London on its new trajectory.2 The possible demographic and economic consequences of this plague have been much debated in the pages of this journal, with a conservative view of its impact generally prevailing. -

Lyle Tompsen, Student Number 28001102, Masters Dissertation

Lyle Tompsen, Student Number 28001102, Masters Dissertation The Mari Lwyd and the Horse Queen: Palimpsests of Ancient ideas A dissertation submitted to the University of Wales Trinity Saint David in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Celtic Studies 2012 Lyle Tompsen 1 Lyle Tompsen, Student Number 28001102, Masters Dissertation Abstract The idea of a horse as a deity of the land, sovereignty and fertility can be seen in many cultures with Indo-European roots. The earliest and most complete reference to this deity can be seen in Vedic texts from 1500 BCE. Documentary evidence in rock art, and sixth century BCE Tartessian inscriptions demonstrate that the ancient Celtic world saw this deity of the land as a Horse Queen that ruled the land and granted fertility. Evidence suggests that she could grant sovereignty rights to humans by uniting with them (literally or symbolically), through ingestion, or intercourse. The Horse Queen is represented, or alluded to in such divergent areas as Bronze Age English hill figures, Celtic coinage, Roman horse deities, mediaeval and modern Celtic masked traditions. Even modern Welsh traditions, such as the Mari Lwyd, infer her existence and confirm the value of her symbolism in the modern world. 2 Lyle Tompsen, Student Number 28001102, Masters Dissertation Table of Contents List of definitions: ............................................................................................................ 8 Introduction .................................................................................................................. -

Year 7 Curriculum Map 2019-20

Curriculum Map 2019-20 Year 7 Year 7 Christmas Easter Summer English Study of class Developing Investigating genre: Study of class Exam preparation Presentations: A novel; poetry and responses to A focus on creative novel; poetry and Revision focus on prose poetry; poetry and writing; poetry and prose developing verbal comprehension; prose prose comprehension; communication. Creative writing comprehension; comprehension; Creative writing (Narrative and Creative writing (developing style Descriptive) (discursive and and structure) persuasive); exam preparation 7S will follow the general pattern but will be stretched by more searching work, extra texts and the addition of specific General Paper material. Maths Number work, algebra and “wordy” problems will be practised throughout the year. Primes – Venn diagrams, HCF / LCM Ratio - using unitary method, Bearings Fractions – addition, subtraction, proportional reasoning, More algebra with equations and multiplication and division speed/distance/time sequences Algebra – substitution, simplification, Rounding to decimal places and Transformations – Translations, brackets and equations, rules of algebra significant figures, powers of 10 and Enlargement and Reflection powers standard form Straight line graphs y=x, plotting y = mx Averages – wordy questions with one + c Percentages value changing and combining averages Converting between km/h and m/s Area, perimeter - including Averages from frequency tables parallelogram, trapezium and triangles SPRING EXAM WEEK Circles and volume Angles in polygons French Prepare Y7 trip to Burgundy: School life + daily routine: to be tested House & Household Tasks: to be A Region is studied & tested this term + this term: opinions & preferences of tested this term: description of house, also includes: description of an area subjects, description of the school garden & area, description of favourite including towns & villages, regional builidings & uniform, daily routine, clubs, room, activities at home including specialities to eat & drink & activities school rules chores. -

GADARG - Essays 09/03/2009 10:47

GADARG - essays 09/03/2009 10:47 GLOUCESTER AND DISTRICT ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESEARCH GROUP Registered charity No.252290 Contact us: ~ GLEVUM ~ The Roman origins of Gloucester by Nigel Spry In 1997 Gloucester celebrated its founding as a Colonia - the highest status to which any Roman settlement could aspire. To learn about this, let's start at the beginning - and then we can follow on with some later history. Kingsholm Some time after AD 49 the Roman army - we cannot be certain but probably the 20th legion or elements of it, from Colchester - built a fortress at Kingsholm near an Iron-Age settlement beside the then course of the Severn. There appears to have been two major phases of construction, the later one bringing the site to full legionary size. The use of the fortress and its continuity of occupation is uncertain, but its probable role was as a strategic base and support headquarters for campaigns in Wales. Because of flooding the location was an unsatisfactory one; this no doubt was one reason that around AD 66 it was abandoned and the army established a new fortress one km to the south, on an area of raised ground that would in due course become known as Gloucester, where there had been earlier occupation. A New Fortress The new fortress, rectangular in shape and covering an area of 17 hectares (43 acres), had turf faced and 'timber strapped' clay ramparts, 3.5m high, surmounted by a timber palisade and walkway, and fronted by wide steeply cut V-shaped ditches. Substantial timber gate towers pierced the rampart on each side and between them along the ramparts were other timber towers at intervals and at the rampart corners. -

Notes for the Teacher: Chapter 3 De Romanis Has Been Designed for a Selective Approach

Notes for the teacher: Chapter 3 de Romanis has been designed for a selective approach. Students need to learn the new vocabulary and grammar from each chapter’s Core Language section, but teachers should select a suitable combination of introductory and practice material to suit the time available and the needs of their students. INTRODUCTORY MATERIAL The notes which follow aim to highlight areas of interest within the theme for each chapter; teachers are encouraged to be selective in accordance with the age and interest of their classes. Overview Chapter 3 introduces gods who were particularly important to the Romans, and highlights the specifically Roman beliefs about some of the main Olympian gods. Roman worship of Jupiter, Venus and Mars is explained, including the role of their temples in important public events and spaces. The household gods, Vesta, Lares and Penates, are introduced next, followed by Janus and then personified deities such as Fortuna. The concept of deification, and specifically the deification of Romulus (Quirinus) and Julius Caesar, follows. Finally, Sulis Minerva and Minerva Belisama are given as examples of the Roman readiness to combine their religion with those of conquered territories. How to begin For all chapters, it is beneficial to read and discuss the introduction in overview before beginning the Core Language material: students will find the Latin sentences and stories more interesting (and more accessible) if they are already familiar with the context behind them. The PowerPoint slides available online might be helpful for teachers keen to offer a compressed introduction; in addition the worksheets (also available online) will direct students’ attention to the most important details in the introduction. -

5E S-13 Samples

NACCP 5e Teaching Materials NACCP offers supplementary teacher-made materials to support classroom teachers who use The Cambridge Latin Course (CLC). Our materials correspond to the Stages in CLC Units 1-4. All materials are available on our website: www.cambridgelatin.org For over 30 years, NACCP has offered materials to support the CLC 4th Edition. Items that reflect vocabulary and storyline changes in the CLC 5th Edition are being added when they become available. Similar to our original materials, these items are organized by 5th Edition Topic area: Culture, Reading, Vocabulary, and Student Self Assessments. On the following pages, we have assembled a cross-section of our 5e Teaching Materials to show representative content and format from each topic area for Stage 13. It provides an opportunity for you to “try before you buy” and determine if our materials will be of value to you in your classroom. The 5th Edition examples that follow include: § Culture – Anticipation Guide § Contextual Vocabulary Quiz § English Comprehension Questions § Latin Comprehension Questions § Student Self Assessments www.cambridgelatin.org Samples – Not Intended for Sale Stage 13 Cultural Anticipation Guide Nomen______________________ I. Directions: Read the following statements carefully and decide whether you agree, disagree, or don't know. • If you agree with the statement, check the column marked C for consentio (I agree) • If you disagree, check D for dissentio (I disagree) • If you do not know, check N for nescio (I do not know). Before reading... After reading... C D N Statement V F Why? Gaius Salvius Liberalis was born in Pompeii and came to Britain after the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. -

Gottheit (99) 1 Von 10

Gottheit (99) Suche Startseite Profil Konto Gottheit Zurück zu Witchways Diskussionsforum Themenübersicht Neues Thema beginnen Thema: Gottheit Thema löschen | Auf dieses Thema antworten Es werden die Beiträge 1 - 30 von 97 angezeigt. 1 2 3 4 Shannah Witchways Abnoba (keltische Muttergöttin) Abnoba war eine keltische Muttergöttin und personifizierte den Schwarzwald, welcher in der Antike den Namen Abnoba mons trug. Mythologie Sie galt als Beschützerin des Waldes, des Wildes und der Quellen, insbesondere als Schutzpatronin der Heilquellen in Badenweiler. Wild und Jäger unterstanden ihrem Schutz. Nach der bei der Interpretatio Romana üblichen Vorgehensweise wurde sie von den Römern mit Diana gleichgesetzt, wie etwa eine in Badenweiler aufgefundene Weiheinschrift eines gewissen Fronto beweist, der damit ein Gelübde einlöste. Wahrscheinlich stand auf dem Sockel, der diese Inschrift trägt, ursprünglich eine Statue dieser Gottheit. Ein in St. Georgen aufgefundenes Bildwerk an der Brigachquelle zeigt Abnoba mit einem Hasen, dem Symbol für Fruchtbarkeit, als Attribut. Tatsächlich wurden in Badenweiler auch Leiden kuriert, die zu ungewollter Kinderlosigkeit führten, und in den Thermen dieses Ortes war ungewöhnlicherweise die Frauenabteilung nicht kleiner als die für Männer. Abnoba dürfte für die Besucher von Badenweiler also vor allem als Fruchtbarkeitsgottheit gegolten haben. vor etwa einem Monat Beitrag löschen Shannah Witchways Aericura (keltische Totengottheit) Aericura ist eine keltisch-germanische Fruchtbarkeits- und Totengottheit. Mythologie Aericura, auch Aeracura, Herecura oder Erecura, ist eine antike keltisch-germanische (nach einigen Theorien jedoch ursprünglich sogar eine illyrische) Gottheit. Sie wird zumeist mit Attributen der Proserpina ähnlich dargestellt, manchmal in Begleitung eines Wolfs oder Hundes, häufig jedoch auch mit ruchtbarkeitsattributen wie Apfelkörben. Manchmal wird Aericura als Fruchtbarkeitsgottheit gedeutet, häufig jedoch eher als Totengöttin. -

CELTIC MYTHOLOGY Ii

i CELTIC MYTHOLOGY ii OTHER TITLES BY PHILIP FREEMAN The World of Saint Patrick iii ✦ CELTIC MYTHOLOGY Tales of Gods, Goddesses, and Heroes PHILIP FREEMAN 1 iv 1 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries. Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America. © Philip Freeman 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer. CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress ISBN 978–0–19–046047–1 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America v CONTENTS Introduction: Who Were the Celts? ix Pronunciation Guide xvii 1. The Earliest Celtic Gods 1 2. The Book of Invasions 14 3. The Wooing of Étaín 29 4. Cú Chulainn and the Táin Bó Cuailnge 46 The Discovery of the Táin 47 The Conception of Conchobar 48 The Curse of Macha 50 The Exile of the Sons of Uisliu 52 The Birth of Cú Chulainn 57 The Boyhood Deeds of Cú Chulainn 61 The Wooing of Emer 71 The Death of Aife’s Only Son 75 The Táin Begins 77 Single Combat 82 Cú Chulainn and Ferdia 86 The Final Battle 89 vi vi | Contents 5. -

Jegens Dè Godin Nehalennia Heeft Placidus

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/26513 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-10-01 and may be subject to change. I BERICHT UIT BRITANNIA In 1976 is in Engeland te York(-Clementhorpe), het Romeinse Eboracum, een stuk gevonden van een plaat van grove zandsteen (“gritstone”), dat secundair gebruikt is in een na-middeleeuwse kalkoven. Van de plaat ís het rechter bovengedeelte bewaard gebleven; dit is 63 x 49 x 14 cm groot. Op de voorzijde zijn nog sporen te zien van een tabula ansata, alsmede een gedeelte van een bijzonder interessante Latijnse inscriptie (pl. 25 A). De vondst is onlangs door dr. R. S.O. Tomlin bekendgemaakt in het aan Romeins Engeland gewijde tijdschrift Britannia, jg. 8, 1977, 430 v., nr. 18. De nieuwste epigrafische aanwinst uit York bevat het eerste gegeven uit Britannia dat rechtstreeks in verband kan worden gebracht met de cultus van Nehalennia in het mondingsgebied van de Schelde. Het belang daarvan is zodanig dat het gerechtvaardigd lijkt er ook in een Nederlands archeologisch tijdschrift de aandacht op te vestigen. Het opschrift luidt: [------]* etg eRio 'LOci / [------Jg g -l -vFdvcivs / [------ ]cidvs-dom o / [--------] VEL10CAS[S] IVM 5/ [--------]eG0TIAT0R / [--------]RCVM ET FANVM / [--------] D'[.] GRATO ET / [--------. Voor de aanvulling van deze tekst kan allereerst gebruik worden gemaakt van het onderste gedeelte van een kalkstenen altaar dat op donderdag 3 september 1970 uit de Oosterschelde is opgevist in het gebied van de gemeente Zierikzee, dicht bij Colijnsplaat (pl. -

Suburani Book 1 Overview

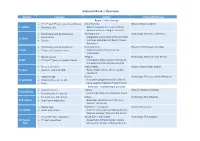

Suburani Book 1 Overview Chapter Language Culture History/Mythology Roma – life in the city • 1st, 2nd and 3rd pers. sg., present tense Life in the city History: Rome in AD 64 1: Subūrai • Reading Latin Subura; Population of city of Rome; Women at work; Living in an insula • Nominative and accusative sg. Building Rome Mythology: Romulus and Remus • Declensions Geography and growth of Rome; Public 2: Rōma • Gender buildings and spaces of Rome; Forum Romanum • Nominative and accusative pl. Entertainment History: Three phases of ruling 3: lūdī • 3rd pers. pl., present tense Public festivals; Chariot-racing; Charioteers • Neuter nouns Religion Mythology: Deucalion and Pyrrha 4: deī • 1st and 2nd pers. pl., present tense Christianity; State religion; Homes of the gods; Sacrifice; Private worship • Present infinitive Public health History: Rome under attack! 5: aqua • possum, volō and nōlō Baths; Public toilets; Water supply; Sanitation • Ablative case Slavery Mythology: Theseus and the Minotaur 6: servitium • Prepositions + acc./+ abl. How were people enslaved? Life of a • Time slave; Seeking freedom; Manumission Britannia – establishing a province • Imperfect tense London History: Romans invading 7: Londīnium • Perfect tense (-v- stems) Londinium; Made in Londinium; Food • Perfect tense (all stems) Britain Mythology: The Amazons 8: Britannia • Superlative adjectives Britannia; Camulodunum; Resist or accept? The Druids • Dative case Rebellion – hard power History: Resistance 9: rebelliō • Verbs with dative Chain of command; Competing forces; Women and war; Why join the army? • 1st and 2nd decl. adjectives Aquae Sulis – soft power Mythology: The Gorgons 10: Aquae • 3rd decl. adjectives Aquae Sulis; Different gods; Curses; Sūlis Military life; People of Roman Britain Gaul and Lusitania – life in a province • Genitive case The sea History: Pirates in the Mediterranean Sea • -ne and -que Romans and the sea; Underwater 11: mare archaeology; Navigation and maps; Dangers at sea • Imperatives (inc. -

Aquae Sulis. the Origins and Development of a Roman Town

7 AQUAE SULIS. THE ORIGINS AND DEVELOPMENT OF A ROMAN TOWN Peter Davenport Ideas about Roman Bath - Aquae Sulis - based on excavation work in the town in the early 1990s were briefly summarised in part of the article I wrote in Bath History Vol.V, in 1994: 'Roman Bath and its Hinterland'. Further studies and excavations in Walcot and the centre of town have since largely confirmed what was said then, but have also added details and raised some interesting new questions. Recent discoveries in other parts of the town have also contributed their portion. In what follows I want to expand my study of the evidence from recent excavations and the implications arising from them. The basic theme of this paper is the site and character of the settlement at Aquae Sulis and its origins. It has always been assumed that the hot springs have been the main and constant factor in the origins of Bath and the development of the town around them. While it would be foolish to deny this completely, the creation of the town seems to be a more complex process and to owe much to other factors. Before considering this we ought to ask, in more general terms, how might a town begin? With certain exceptions, there was nothing in Britain before the Roman conquest of AD43 that we, or perhaps the Romans, would recognise as a town. Celtic Britain was a deeply rural society. The status of hill forts, considered as towns or not as academic fashion changes, is highly debatable, but they probably acted as central places, where trade and social relationships were articulated or carried on in an organized way.