Correlates of Lifetime Blunt/Spliff Use Among Cigarette Smokers in Substance Use Disorders Treatment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Section 5: Smoking Regulations for Food Service Establishments

Section 5: Smoking Regulations Statement of Purpose Whereas there exists conclusive evidence that tobacco smoke causes cancer, respiratory and cardiac diseases, negative birth outcomes, irritations to the eyes, nose and throat; and whereas more than eighty percent of all smokers begin smoking before the age of eighteen years (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, "Youth Surveillance - United States 2000," 50 MMWR 1(Nov. 2000); and whereas nationally in 2000, sixty nine percent of middle school age children who smoke at least once a month were not asked to show proof of age when purchasing cigarettes (Id.); and whereas the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has concluded that nicotine is as addictive as cocaine or heroin; and whereas the Institute of Medicine (IOM) concludes that raising the minimum age of legal access to tobacco products to 21 will reduce tobacco initiation, particularly among adolescents 15 – 17, and will improve health across the lifespan and save lives; and whereas sales of flavored little cigars increased by 23% between 2008 and 2010 and many non-cigarette tobacco products, such as cigars and cigarillos, can be sold in a single “dose;” enjoy a relatively low tax as compared to cigarettes; are available in fruit, candy and alcohol flavors; and are popular among youth; and whereas the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the U.S. Surgeon General have stated that flavored tobacco products are considered to be “starter” products that help establish smoking habits that can lead to long-term addiction; and whereas despite state laws prohibiting the sale of tobacco products to minors, access by minors to tobacco products is a major problem; and whereas the sale of tobacco products is incompatible with the mission of health care institutions because it is detrimental to the public health and undermines efforts to educate patients on the safe and effective use of medication; now, therefore it is the intention of the Wareham Board of Health to regulate the access of tobacco products. -

Other Tobacco Products (OTP) Are Products Including Smokeless and “Non-Cigarette” Materials

Other tobacco products (OTP) are products including smokeless and “non-cigarette” materials. For more information on smoking and how to quit using tobacco products, check out our page on tobacco. A tobacco user may actually absorb more nicotine from chewing tobacco or snuff than they do from a cigarette (Mayo Clinic). The health consequences of smokeless tobacco use include oral, throat and pancreatic cancer, tooth loss, gum disease and increased risk of heart disease, heart attack and stroke. (American Cancer Society, “Smokeless Tobacco” 2010) Smokeless tobacco products contain at least 28 cancer-causing agents. The risk of certain types of cancer increases with smokeless tobacco: Esophageal cancer, oral cancer (cancer of the mouth, throat, cheek, gums, lips, tongue). Other Tobacco Products (OTP) Include: Chewing/Spit Tobacco A smokeless tobacco product consumed by placing a portion of the tobacco between the cheek and gum or upper lip teeth and chewing. Must be manually crushed with the teeth to release flavor and nicotine. Spitting is required to get rid of the unwanted juices. Loose Tobacco Loose (pipe) tobacco is made of cured and dried leaves; often a mix of various types of leaves (including spiced leaves), with sweeteners and flavorings added to create an "aromatic" flavor. The tobacco used resembles cigarette tobacco, but is more moist and cut more coarsely. Pipe smoke is usually held in the mouth and then exhaled without inhaling into the lungs. Blunt Wraps Blunt wraps are hollowed out tobacco leaf to be filled by the consumer with tobacco (or other drugs) and comes in different flavors. Flavors are added to create aromas and flavors. -

FLAVORED TOBACCO PRODUCTS Flavored Tobacco Products Are Tempting to Youth

2008 YTS REPORT: FLAVORED TOBACCO PRODUCTS Flavored Tobacco Products are Tempting to Youth Fighting to protect youth Under the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act of 2009, the The 2008 Indiana Youth Tobacco Survey provides the latest information on U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) banned candy and fruit-fl avored the use of fl avored tobacco products by Indiana youth. cigarettes. However, the ban does not include other types of fl avored tobacco products such as smokeless tobacco or cigars. It is widely known 1 Carpenter, C.M., G.F. Wayne, J.L. Pauly, H.K.Koh, and G.N. Connolly. 2005. “New Cigarette that fl avored tobacco products are tempting to youth and tobacco industry Brands With Flavors That Appeal to Youth: Tobacco Marketing Strategies.” Health Affairs 24(6): 1601-1610. documents have revealed strategies to add fl avors to tobacco products that 2 1 Manning, K.C., Kelly, K.J., and Comello, M.L. 2009. “Flavoured cigarettes, sensation seeking are appealing to young people . With the changes in regulations, many and adolescents’ perceptions of cigarette brands.” Tobacco Control, 18: 459-465. experts believe tobacco companies have already taken a different marketing tactic to now market their fl avored smokeless and cigar products. Flavor additives, including chocolate, lime, orange and mint as well as menthol, can mask the harsh unpleasant taste and odor of tobacco; this could ultimately entice and make it easier for youth to use tobacco products. Despite the mild presentation, these fl avored products offer the same health risks and consequences as unfl avored tobacco products. -

Blunts and Blowt Jes: Cannabis Use Practices in Two Cultural Settings

Free Inquiry In Creative Sociology Volume 31 No. 1 May 2003 3 BLUNTS AND BLOWTJES: CANNABIS USE PRACTICES IN TWO CULTURAL SETTINGS AND THEIR IMPLICATIONS FOR SECONDARY PREVENTION Stephen J. Sifaneck, Institute for Special Populations Research, National Development & Research Institutes, Inc. Charles D. Kaplan, Limburg University, Maastricht, The Netherlands. Eloise Dunlap, Institute for Special Populations Research, NDRI. and Bruce D. Johnson, Institute for Special Populations Research, NDRI. ABSTRACT Thi s paper explores two modes of cannabis preparati on and smoking whic h have manifested within the dru g subcultures of th e United States and the Netherlan ds. Smoking "blunts," or hollowed out cigar wrappers fill ed wi th marijuana, is a phenomenon whi ch fi rst emerged in New York Ci ty in the mid 1980s, and has since spread throughout th e United States. A "bl owtj e," (pronounced "blowt-cha") a modern Dutch style j oint whi ch is mixed with tobacco and in cludes a card-board fi lte r and a longer rolling paper, has become th e standard mode of cannabis smoking in the Netherl ands as well as much of Europe. Both are consid ered newer than the more traditi onal practi ces of preparin g and smoking cannabis, including the traditional fi lter-less style joint, the pot pipe, an d the bong or water pipe. These newer styles of preparati on and smoking have implications for secondary preventi on efforts wi th ac tive youn g cannabis users. On a social and ritualistic level th ese practices serve as a means of self-regulating cannabi s use. -

How Other Countries Regulate Flavored Tobacco Products / 1

How Other Countries Regulate Flavored Tobacco Products / 1 How Other Countries Regulate Flavored Tobacco Products In 2009, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, under authority granted by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, prohibited the manufacturing, marketing, and sale of cigarettes containing “characterizing flavors,” such as vanilla, chocolate, cherry, and coffee. This prohibition extends to flavored cigarettes and flavored cigarette “component parts,” such as their tobacco, filter or paper. However, the prohibition exempts the flavors of menthol and tobacco and does not apply to non-cigarette tobacco products, such as electronic cigarettes, cigars, smokeless tobacco, hookah tobacco, and their flavored component parts. Other countries have enacted more robust regulations regarding flavored tobacco products. Below is a summary of select flavored tobacco restrictions from around the world.* European Union. In 2014, the European Union (representing 28 member states) passed a new Tobacco Products Directive that includes: • A ban on flavorings (other than menthol) in cigarettes and RYO tobacco as of May 20, 2016 • A ban on flavor capsules in tobacco products as of May 20, 2016 • A ban on menthol cigarettes and RYO tobacco as of May 20, 2020 Australia. A number of states and territories (including Australian Capital Territory, New South Wales, Victoria, and South Australia) have legislation that delegates authority to their Health Ministers to prohibit tobacco products or classes of tobacco products that have a distinctive fruity, sweet, or confectionery-like character and/or that might encourage a minor to smoke (or where the smoke may do so). Brazil. In 2012, Brazil became the first country to adopt a ban of all tobacco product flavors and additives, including menthol. -

“I Just Use It for Weed”: the Modification of Little Cigars and Cigarillos by Young Adult African American Male Users

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author J Ethn Subst Manuscript Author Abuse. Author Manuscript Author manuscript; available in PMC 2018 May 09. Published in final edited form as: J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2017 ; 16(1): 66–79. doi:10.1080/15332640.2015.1081117. “I just use it for weed”: The modification of little cigars and cigarillos by young adult African American male users Sarah J. Koopman Gonzaleza, Leslie E. Cofieb, and Erika S. Trapla aDepartment of Epidemiology & Biostatistics, Prevention Research Center for Healthy Neighborhoods, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio bDepartment of Health Behavior, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina Abstract Little cigar and cigarillo (LCC) use has received increased attention, but research on their modification is limited. Qualitative interviews with 17 young adult African American male LCC users investigated tobacco use behaviors and patterns, including LCC modification. The modification of LCCs for use as blunts emerged as a very prominent aspect of LCC users’ tobacco use. Four subthemes regarding marijuana and blunt use are explored in this article, including participants’ explanations of how blunts are made and used, concurrent use of marijuana and tobacco, perceptions and reasons for smoking marijuana and blunts, and perceptions of the risks of blunt use. Keywords Blunts; cigarillos; little cigars; marijuana Introduction Little cigar and cigarillo (LCC) use has received increased attention in research in the past decade as rates of LCC use rise (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012; Cullen et al., 2011). LCCs have been shown to be common among African American men (Borawski et al., 2010; Cullen et al., 2011; Montgomery, 2015) and among youth and young adults (Arrazola et al., 2015; Richardson, Rath, Ganz, Xiao, & Vallone, 2013). -

Cigars, Little Cigars, and 3

the truth about little cigars, cigarillos & cigars BACKGROUND • Cigars are defined in the United States (U.S.) tax code as “any roll of tobacco wrapped in leaf tobacco or in any substance containing tobacco” that does not meet the definition of a cigarette.1 • However, despite those definitions, cigars are a heterogeneous product category, with at least three major cigar products—little cigars, cigarillos and large cigars.2 • Little Cigars (aka small cigars) weigh less than 3 lbs/1000 and resemble cigarettes.3 Cigarettes are wrapped in white paper, CIGARETTE while little cigars are wrapped in brown paper that contains some tobacco leaf. Generally, little cigars have a filter like a LITTLE CIGAR cigarette.4 • Cigarillos weigh more than 3 lbs/1000 and are classified as “large” cigars by federal tax code.2 Cigarillos are longer, slimmer versions of large cigars. Cigarillos do not CIGARILLO (TIPPED AND UNTIPPED) usually have a filter, but sometimes have wood or plastic tips.2 • Traditional (aka large cigars) weigh more than 3 pounds/10002 and are also referred CIGAR to as “stogies.” • Little cigars, cigarillos, and large cigars are offered in a variety of flavors including candy and fruit flavors such as sour apple, cherry, grape, chocolate and menthol.5,6 • Until recently, cigars were not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). However, in May 2016, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) finalized its “deeming” regulation, extending its authority to little cigars, cigarillos, and premium cigars, as well as to components and parts such as rolling papers and filters. This authority does not extend to accessories such as lighters and cutters.7 This means that FDA can now issue product standards to make all cigars less appealing, toxic and addictive, and it can issue marketing restrictions like those in place for cigarettes, in order to keep cigars out of the hands of kids. -

State of Tobacco Control 2021” Evaluating States on Whether They Have Prohibited the Sale of All Flavored Tobacco Products

2 Lung.org American Lung Association “State of Tobacco Control” 2021 “State of Tobacco Control” 2021: Preventing and Reducing Tobacco Use During the Time of COVID-19 The 19th annual American Lung Association “State of Tobacco Control” report evaluates states and the federal government on actions taken to eliminate the nation’s leading cause of preventable death—tobacco use—and save lives with proven-effective and urgently needed tobacco control laws and policies. The COVID-19 pandemic was clearly the main story of 2020, causing hundreds of thousands of deaths and disrupting the lives of everyone in the country. The U.S. Surgeon General has conclusively linked smoking to suppression of the immune system, and smoking increases the risk for severe illness from COVID-19, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). With the threat of COVID-19 in addition to the numerous tobacco-caused diseases, it is imperative to prevent youth from starting to use tobacco and to help everyone quit. Much like how COVID-19 has a disproportionate impact on certain communities, especially communities of color, so does tobacco use and exposure to secondhand smoke. Menthol cigarettes remain a key vector for tobacco-related death and disease in Black communities, with over 80% of Black Americans who smoke using them. Menthol cigarette use is Menthol in cigarettes plays also elevated among LGBTQ+ Americans, pregnant women and persons a significant role in youth with lower incomes. A recent study showed that while overall cigarette use declined by 26% over the past decade, 91% of that decline was becoming addicted to due to non-menthol cigarettes.1 This underscores what an FDA scientific cigarettes, masking the harsh advisory committee already found:2 menthol cigarettes are hard to quit, and taste of tobacco smoke and disproportionately affects Black communities.3 In addition, secondhand making the smoke easier to smoke exposure also occurs most often in hospitality establishments such as bars and casinos where people from Black and Brown communities more inhale. -

Flavour Chemicals in a Sample of Non-Cigarette Tobacco Products

TC Online First, published on April 11, 2017 as 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053552 Tob Control: first published as 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053552 on 11 April 2017. Downloaded from Research paper Flavour chemicals in a sample of non-cigarette tobacco products without explicit flavour names sold in New York City in 2015 Shannon M Farley,1 Kevin RJ Schroth,1 Victoria Grimshaw,1 Wentai Luo,2,3 Julia L DeGagne,3 Peyton A Tierney,3 Kilsun Kim,2 James F Pankow2,3 ► Additional material is ABSTRACT or natural flavor…. that is a characterizing flavor of published online only. To view Background Youth who experiment with tobacco often the tobacco product or tobacco smoke’. Note that please visit the journal online (http:// dx. doi. org/ 10. 1136/ start with flavoured products. In New York City (NYC), lo- low levels of flavour additives that do not yield a tobaccocontrol- 2016- 053552) cal law restricts sales of all tobacco products with ‘char- ‘characterising flavour’ are neither banned nor more acterising flavours’ except for ‘tobacco, menthol, mint explicitly defined. The FSPTCA does authorise the 1NYC Department of Health and wintergreen’. Enforcement is based on packaging: Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to mandate and Mental Hygiene, Bureau of explicit use of a flavour name (eg, ‘strawberry’) or image disclosures to the FDA on constituents, ingredients Chronic Disease Prevention and Tobacco Control, Long Island depicting a flavour (eg, a fruit) is presumptive evidence and additives, which could be used to require disclo- City, New York, USA that a product is flavoured and therefore prohibited. sures of flavourings for all regulated tobacco prod- 2Department of Chemistry, However, a tobacco product may contain significant ucts. -

Blunt Wrap Presentation

Blunt Wrap Presentation Dallas City Council Public Safety Committee Meeting August 2, 2010 Cigar Association of America Craig Williamson Robert Peeler What are "blunt wraps" used for? "Blunt wraps are primarily intended for use with marijuana or cannabis." "Blunt wraps constitute drug paraphernalia." SOURCE: US Customs and Border Protection Agency ruling, November 26, 2008 "Blunt wraps are heavily marketed to the youth and often used as drug paraphernalia." Source: City of Boston Public Health Commission Ordinance, adopted December 11, 2008 "According to focus groups with teens, blunts remain the most popular form for smoking cannabis." Source: National Institute on Drug Abuse, Community Epidemiology Work Group Report, "Epidemiological Trends in Drug Abuse " "While blunts generally contain more marijuana than a regular joint, they look like a regular cigar." Tobacco Technical Assistance Consortium ‐ Tobacco 101/Tobacco Products, See www.ttac.org "Blunts may be laced with other substances including PCP and crack cocaine." Source: National Institute on Drug Abuse, Community Epidemiology Work Group Report, "Epidemiological Trends in Drug Abuse" 2 “It is quite evident from the vast number references on the Internet that blunt wraps are sold and bought for use with marijuana or cannabis.” SOURCE: US Customs and Border Protection Agency ruling, November 26, 2008 A cursory search of the internet will return thousands of results relating blunt wraps to illegal drug use. For example, the website grasscity.com shows the following guide on how to roll your own marijuana blunt using blunt wraps: 3 Blunt Wraps Are Marketed With Obvious Drug References 4 Blunt Wraps Are Now Being Marketed as “Cigar Wraps” In An Attempt to Legitimize the Product ‐A Distinction Without a Difference‐ Changing the label on package from “blunt wrap” to “cigar wrap” does not change the fact that the product inside the package is the same product that U.S. -

BRANDY's PRODUCTS, INC., NOT FINAL UNTIL TIME EXPIRES to FILE MOTION for REHEARING and Appellant, DISPOSITION THEREOF IF FILED V

IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF APPEAL FIRST DISTRICT, STATE OF FLORIDA BRANDY'S PRODUCTS, INC., NOT FINAL UNTIL TIME EXPIRES TO FILE MOTION FOR REHEARING AND Appellant, DISPOSITION THEREOF IF FILED v. CASE NO. 1D15-3101 DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS AND PROFESSIONAL REGULATION, DIVISION OF ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES AND TOBACCO, Appellee. _____________________________/ Opinion filed April 6, 2016. An appeal from the Department of Business and Professional Regulation. Gerald J. Donnini II, Joseph C. Moffa, and James McAuley, of Moffa, Gainor, & Sutton, P.A., Fort Lauderdale, for Appellant. Pamela Jo Bondi, Attorney General, and Elizabeth Teegen, Assistant Attorney General, Tallahassee, for Appellee. WETHERELL, J. In this administrative appeal, Appellant contends that the final order issued by Appellee (the agency) erroneously determined that the cigar wraps – or, as they are colloquially known, “blunt wraps” – distributed by Appellant constitute “loose tobacco suitable for smoking” under the definition of “tobacco products” in section 210.25(11), Florida Statutes. We agree. Accordingly, we reverse the final order. In March 2013, the agency notified Appellant that it owed almost $72,000 in taxes, surcharges, penalties, and interest (the assessment) on the blunt wraps it distributed to Florida retailers from July 1, 2009,1 through August 2011. Appellant challenged the assessment and the dispute was referred to the Division of Administrative Hearings for a formal administrative hearing. After the hearing, the administrative law judge (ALJ) issued an order recommending that the assessment be set aside because “a blunt wrap is no more loose tobacco than a piece of writing paper is loose wood.” The agency rejected the ALJ’s recommendation (and the legal conclusions on which it was based) and issued a final order directing Appellant to pay the assessment in full. -

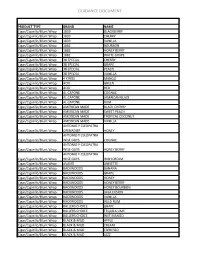

MAHB Flavored Tobacco Guidance List 10.1.15

GUIDANCE DOCUMENT PRODUCT TYPE BRAND NAME Cigar/Cigarillo/Blunt Wrap 1839 BLACKBERRY Cigar/Cigarillo/Blunt Wrap 1839 CHERRY Cigar/Cigarillo/Blunt Wrap 1839 VANILLA Cigar/Cigarillo/Blunt Wrap 1882 BOURBON Cigar/Cigarillo/Blunt Wrap 1882 HONEY BERRY Cigar/Cigarillo/Blunt Wrap 1882 WHITE GRAPE Cigar/Cigarillo/Blunt Wrap 38 SPECIAL CHERRY Cigar/Cigarillo/Blunt Wrap 38 SPECIAL GRAPE Cigar/Cigarillo/Blunt Wrap 38 SPECIAL PEACH Cigar/Cigarillo/Blunt Wrap 38 SPECIAL VANILLA Cigar/Cigarillo/Blunt Wrap 4 KINGS MANGO Cigar/Cigarillo/Blunt Wrap ACID GREEN Cigar/Cigarillo/Blunt Wrap ACID RED Cigar/Cigarillo/Blunt Wrap AL CAPONE COGNAC Cigar/Cigarillo/Blunt Wrap AL CAPONE JAMAICAN BLAZE Cigar/Cigarillo/Blunt Wrap AL CAPONE RUM Cigar/Cigarillo/Blunt Wrap AMERICAN MADE BLACK CHERRY Cigar/Cigarillo/Blunt Wrap AMERICAN MADE SWEET PEACH Cigar/Cigarillo/Blunt Wrap AMERICAN MADE TROPICAL COCONUT Cigar/Cigarillo/Blunt Wrap AMERICAN MADE VANILLA ANTONIO Y CLEOPATRA Cigar/Cigarillo/Blunt Wrap GRENADIER HONEY ANTONIO Y CLEOPATRA Cigar/Cigarillo/Blunt Wrap WISE GUYS COGNAC ANTONIO Y CLEOPATRA Cigar/Cigarillo/Blunt Wrap WISE GUYS HONEY BERRY ANTONIO Y CLEOPATRA Cigar/Cigarillo/Blunt Wrap WISE GUYS IRISH CREAM Cigar/Cigarillo/Blunt Wrap AVANTI ANISETTE Cigar/Cigarillo/Blunt Wrap BACKWOODS BANANA Cigar/Cigarillo/Blunt Wrap BACKWOODS GRAPE Cigar/Cigarillo/Blunt Wrap BACKWOODS HONEY Cigar/Cigarillo/Blunt Wrap BACKWOODS HONEY BERRY Cigar/Cigarillo/Blunt Wrap BACKWOODS HONEY BOURBON Cigar/Cigarillo/Blunt Wrap BACKWOODS JAVA FUSION Cigar/Cigarillo/Blunt Wrap BACKWOODS