Human NK Cell Repertoire Diversity Reflects Immune Experience and Correlates with Viral Susceptibility

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse

Welcome to More Choice CD Marker Handbook For more information, please visit: Human bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/humancdmarkers Mouse bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/mousecdmarkers Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse CD3 CD3 CD (cluster of differentiation) molecules are cell surface markers T Cell CD4 CD4 useful for the identification and characterization of leukocytes. The CD CD8 CD8 nomenclature was developed and is maintained through the HLDA (Human Leukocyte Differentiation Antigens) workshop started in 1982. CD45R/B220 CD19 CD19 The goal is to provide standardization of monoclonal antibodies to B Cell CD20 CD22 (B cell activation marker) human antigens across laboratories. To characterize or “workshop” the antibodies, multiple laboratories carry out blind analyses of antibodies. These results independently validate antibody specificity. CD11c CD11c Dendritic Cell CD123 CD123 While the CD nomenclature has been developed for use with human antigens, it is applied to corresponding mouse antigens as well as antigens from other species. However, the mouse and other species NK Cell CD56 CD335 (NKp46) antibodies are not tested by HLDA. Human CD markers were reviewed by the HLDA. New CD markers Stem Cell/ CD34 CD34 were established at the HLDA9 meeting held in Barcelona in 2010. For Precursor hematopoetic stem cell only hematopoetic stem cell only additional information and CD markers please visit www.hcdm.org. Macrophage/ CD14 CD11b/ Mac-1 Monocyte CD33 Ly-71 (F4/80) CD66b Granulocyte CD66b Gr-1/Ly6G Ly6C CD41 CD41 CD61 (Integrin b3) CD61 Platelet CD9 CD62 CD62P (activated platelets) CD235a CD235a Erythrocyte Ter-119 CD146 MECA-32 CD106 CD146 Endothelial Cell CD31 CD62E (activated endothelial cells) Epithelial Cell CD236 CD326 (EPCAM1) For Research Use Only. -

Supplementary Table 1: Adhesion Genes Data Set

Supplementary Table 1: Adhesion genes data set PROBE Entrez Gene ID Celera Gene ID Gene_Symbol Gene_Name 160832 1 hCG201364.3 A1BG alpha-1-B glycoprotein 223658 1 hCG201364.3 A1BG alpha-1-B glycoprotein 212988 102 hCG40040.3 ADAM10 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 10 133411 4185 hCG28232.2 ADAM11 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 11 110695 8038 hCG40937.4 ADAM12 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 (meltrin alpha) 195222 8038 hCG40937.4 ADAM12 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 (meltrin alpha) 165344 8751 hCG20021.3 ADAM15 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 15 (metargidin) 189065 6868 null ADAM17 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 17 (tumor necrosis factor, alpha, converting enzyme) 108119 8728 hCG15398.4 ADAM19 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 19 (meltrin beta) 117763 8748 hCG20675.3 ADAM20 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 20 126448 8747 hCG1785634.2 ADAM21 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 21 208981 8747 hCG1785634.2|hCG2042897 ADAM21 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 21 180903 53616 hCG17212.4 ADAM22 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 22 177272 8745 hCG1811623.1 ADAM23 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 23 102384 10863 hCG1818505.1 ADAM28 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 28 119968 11086 hCG1786734.2 ADAM29 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 29 205542 11085 hCG1997196.1 ADAM30 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 30 148417 80332 hCG39255.4 ADAM33 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 33 140492 8756 hCG1789002.2 ADAM7 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 7 122603 101 hCG1816947.1 ADAM8 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 8 183965 8754 hCG1996391 ADAM9 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 9 (meltrin gamma) 129974 27299 hCG15447.3 ADAMDEC1 ADAM-like, -

Reascreen™ MAX Kit, Human, FFPE, Version 01 Panel Composition – 89 Antibody Conjugates # 130-127-847

REAscreen™ MAX Kit, human, FFPE, version 01 Panel composition – 89 antibody conjugates # 130-127-847 REAscreen MAX Antibody Plate 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 IRF-7 CD104 CD158i CD181 CD295 A pS477/ SSRP1 CD45RA ZAP70 TTF-1 CD138 Sox2 (Integrin CD162 (KIR2DS4) (CXCR1) (LEPR) pS479 β4) CD134 B CD240DCE IRF-7 CD15 CD43 AN2 Galectin-3 CD66c TOM22 CD147 CD66acde (OX40) Cyto- CD279 CD234 C Syk Slug LRP-4 IgD Vimentin Dectin-1 Galectin-9 keratin CLA (PD1) (DARC) PAX-5 CD195 CD196 CD88 CD305 D FAK pS910 p53 FcεRIα PCNA CD268 BMI-1 (BSAP) (CCR5) (CCR6) (C5AR) (LAIR-1) CD334 CD45R CD226 AKT Pan E PKCα BATF Bcl-2 CD65 CD223 CD52 CD66abce (FGFR4) (B220) (DNAM-1) (PKB) CD182 CD20 CD326 Cyto- Podo- HLA-DR, F Cyto- CD45 MLC2v CD66b Hsp70 CD45RB (CXCR2) plasmic (EpCAM) keratin 8 planin DP, DQ CD235a α-Actinin CD202b CD317 G Dnmt3b Jak1 SUSD2 EZH2 (Glycopho (Sarco- CD79a CD40 CD99 (TIE-2) (BST2) rin A) meric) p120 CD239 CD271 H Catenin CD44 CD57 CD123 Ki-67 CD233 CD45RO β-Catenin CD100 (BCAM) (LNGFR) pS879 Antigen Clone Fluorochrome Antibody type Plate position AKT Pan (PKB) REA676 PE REAfinity™ E11 AN2 REA989 PE REAfinity B6 BATF REA486 FITC REAfinity E2 1 Antigen Clone Fluorochrome Antibody type Plate position Bcl-2 REA872 FITC REAfinity E5 BMI-1 REA438 FITC REAfinity D10 CD100 REA316 FITC REAfinity H11 CD104 (Integrin β4) REA236 FITC REAfinity A10 CD123 REA918 FITC REAfinity H5 CD134 (OX40) ACT35 FITC Hybridoma B1 CD138 44F9 FITC Hybridoma A8 CD147 REA282 FITC REAfinity B10 CD15 VIMC6 FITC Hybridoma B4 CD158i (KIR2DS4) JJC11.6 PE Hybridoma A1 CD162 REA319 -

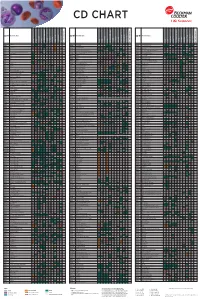

Flow Reagents Single Color Antibodies CD Chart

CD CHART CD N° Alternative Name CD N° Alternative Name CD N° Alternative Name Beckman Coulter Clone Beckman Coulter Clone Beckman Coulter Clone T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells CD1a T6, R4, HTA1 Act p n n p n n S l CD99 MIC2 gene product, E2 p p p CD223 LAG-3 (Lymphocyte activation gene 3) Act n Act p n CD1b R1 Act p n n p n n S CD99R restricted CD99 p p CD224 GGT (γ-glutamyl transferase) p p p p p p CD1c R7, M241 Act S n n p n n S l CD100 SEMA4D (semaphorin 4D) p Low p p p n n CD225 Leu13, interferon induced transmembrane protein 1 (IFITM1). p p p p p CD1d R3 Act S n n Low n n S Intest CD101 V7, P126 Act n p n p n n p CD226 DNAM-1, PTA-1 Act n Act Act Act n p n CD1e R2 n n n n S CD102 ICAM-2 (intercellular adhesion molecule-2) p p n p Folli p CD227 MUC1, mucin 1, episialin, PUM, PEM, EMA, DF3, H23 Act p CD2 T11; Tp50; sheep red blood cell (SRBC) receptor; LFA-2 p S n p n n l CD103 HML-1 (human mucosal lymphocytes antigen 1), integrin aE chain S n n n n n n n l CD228 Melanotransferrin (MT), p97 p p CD3 T3, CD3 complex p n n n n n n n n n l CD104 integrin b4 chain; TSP-1180 n n n n n n n p p CD229 Ly9, T-lymphocyte surface antigen p p n p n -

Characteristics of B Cell-Associated Gene Expression in Patients With

MOLECULAR MEDICINE REPORTS 13: 4113-4121, 2016 Characteristics of B cell-associated gene expression in patients with coronary artery disease WENWEN YAN*, HAOMING SONG*, JINFA JIANG, WENJUN XU, ZHU GONG, QIANGLIN DUAN, CHUANGRONG LI, YUAN XIE and LEMIN WANG Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Cardiology, Tongji Hospital, Tongji University School of Medicine, Shanghai 200065, P.R. China Received May 19, 2015; Accepted February 12, 2016 DOI: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5029 Abstract. The current study aimed to identify differentially with the two other groups. Additionally the gene expression expressed B cell-associated genes in peripheral blood mono- levels of B cell regulatory genes were measured. In patients nuclear cells and observe the changes in B cell activation at with AMI, CR1, LILRB2, LILRB3 and VAV1 mRNA expres- different stages of coronary artery disease. Groups of patients sion levels were statistically increased, whereas, CS1 and IL4I1 with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and stable angina (SA), mRNAs were significantly reduced compared with the SA and as well as healthy volunteers, were recruited into the study control groups. There was no statistically significant difference (n=20 per group). Whole human genome microarray analysis in B cell-associated gene expression levels between patients was performed to examine the expression of B cell-associated with SA and the control group. The present study identified the genes among these three groups. The mRNA expression levels downregulation of genes associated with BCRs, B2 cells and of 60 genes associated with B cell activity and regulation were B cell regulators in patients with AMI, indicating a weakened measured using reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase T cell-B cell interaction and reduced B2 cell activation during chain reaction. -

Snipa Snpcard

SNiPAcard Block annotations Block info genomic range chr19:55,117,749-55,168,602 block size 50,854 bp variant count 74 variants Basic features Conservation/deleteriousness Linked genes μ = -0.557 [-4.065 – AC009892.10 , AC009892.5 , AC009892.9 , AC245036.1 , AC245036.2 , phyloP 2.368] gene(s) hit or close-by AC245036.3 , AC245036.4 , AC245036.5 , AC245036.6 , LILRA1 , LILRB1 , LILRB4 , MIR8061 , VN1R105P phastCons μ = 0.059 [0 – 0.633] eQTL gene(s) CTB-83J4.2 , LILRA1 , LILRA2 , LILRB2 , LILRB5 , LILRP1 μ = -0.651 [-4.69 – 2.07] AC008984.5 , AC008984.5 , AC008984.6 , AC008984.6 , AC008984.7 , AC008984.7 , AC009892.10 , AC009892.10 , AC009892.2 , AC009892.2 , AC009892.5 , AC010518.3 , AC010518.3 , AC011515.2 , AC011515.2 , AC012314.19 , AC012314.19 , FCAR , FCAR , FCAR , FCAR , FCAR , FCAR , FCAR , FCAR , FCAR , FCAR , KIR2DL1 , KIR2DL1 , KIR2DL1 , KIR2DL1 , KIR2DL1 , KIR2DL1 , KIR2DL1 , KIR2DL1 , KIR2DL1 , KIR2DL1 , KIR2DL1 , KIR2DL1 , KIR2DL1 , KIR2DL1 , KIR2DL1 , KIR2DL1 , KIR2DL1 , KIR2DL1 , KIR2DL1 , KIR2DL1 , KIR2DL1 , KIR2DL1 , KIR2DL1 , KIR2DL1 , KIR2DL1 , KIR2DL3 , KIR2DL3 , KIR2DL3 , KIR2DL3 , KIR2DL3 , KIR2DL3 , KIR2DL3 , KIR2DL3 , KIR2DL3 , KIR2DL3 , KIR2DL3 , KIR2DL3 , KIR2DL3 , KIR2DL3 , KIR2DL3 , KIR2DL3 , KIR2DL3 , KIR2DL3 , KIR2DL3 , KIR2DL3 , KIR2DL4 , KIR2DL4 , KIR2DL4 , KIR2DL4 , KIR2DL4 , KIR2DL4 , KIR2DL4 , KIR2DL4 , KIR2DL4 , KIR2DL4 , KIR2DL4 , KIR2DL4 , KIR2DL4 , KIR2DL4 , KIR2DL4 , KIR2DL4 , KIR2DL4 , KIR2DL4 , KIR2DL4 , KIR2DL4 , KIR2DL4 , KIR2DL4 , KIR2DL4 , KIR2DL4 , KIR2DL4 , KIR2DL4 , KIR2DL4 , KIR2DL4 , -

Supplementary Material DNA Methylation in Inflammatory Pathways Modifies the Association Between BMI and Adult-Onset Non- Atopic

Supplementary Material DNA Methylation in Inflammatory Pathways Modifies the Association between BMI and Adult-Onset Non- Atopic Asthma Ayoung Jeong 1,2, Medea Imboden 1,2, Akram Ghantous 3, Alexei Novoloaca 3, Anne-Elie Carsin 4,5,6, Manolis Kogevinas 4,5,6, Christian Schindler 1,2, Gianfranco Lovison 7, Zdenko Herceg 3, Cyrille Cuenin 3, Roel Vermeulen 8, Deborah Jarvis 9, André F. S. Amaral 9, Florian Kronenberg 10, Paolo Vineis 11,12 and Nicole Probst-Hensch 1,2,* 1 Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, 4051 Basel, Switzerland; [email protected] (A.J.); [email protected] (M.I.); [email protected] (C.S.) 2 Department of Public Health, University of Basel, 4001 Basel, Switzerland 3 International Agency for Research on Cancer, 69372 Lyon, France; [email protected] (A.G.); [email protected] (A.N.); [email protected] (Z.H.); [email protected] (C.C.) 4 ISGlobal, Barcelona Institute for Global Health, 08003 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] (A.-E.C.); [email protected] (M.K.) 5 Universitat Pompeu Fabra (UPF), 08002 Barcelona, Spain 6 CIBER Epidemiología y Salud Pública (CIBERESP), 08005 Barcelona, Spain 7 Department of Economics, Business and Statistics, University of Palermo, 90128 Palermo, Italy; [email protected] 8 Environmental Epidemiology Division, Utrecht University, Institute for Risk Assessment Sciences, 3584CM Utrecht, Netherlands; [email protected] 9 Population Health and Occupational Disease, National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College, SW3 6LR London, UK; [email protected] (D.J.); [email protected] (A.F.S.A.) 10 Division of Genetic Epidemiology, Medical University of Innsbruck, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria; [email protected] 11 MRC-PHE Centre for Environment and Health, School of Public Health, Imperial College London, W2 1PG London, UK; [email protected] 12 Italian Institute for Genomic Medicine (IIGM), 10126 Turin, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +41-61-284-8378 Int. -

Whole Exome Sequencing in Families at High Risk for Hodgkin Lymphoma: Identification of a Predisposing Mutation in the KDR Gene

Hodgkin Lymphoma SUPPLEMENTARY APPENDIX Whole exome sequencing in families at high risk for Hodgkin lymphoma: identification of a predisposing mutation in the KDR gene Melissa Rotunno, 1 Mary L. McMaster, 1 Joseph Boland, 2 Sara Bass, 2 Xijun Zhang, 2 Laurie Burdett, 2 Belynda Hicks, 2 Sarangan Ravichandran, 3 Brian T. Luke, 3 Meredith Yeager, 2 Laura Fontaine, 4 Paula L. Hyland, 1 Alisa M. Goldstein, 1 NCI DCEG Cancer Sequencing Working Group, NCI DCEG Cancer Genomics Research Laboratory, Stephen J. Chanock, 5 Neil E. Caporaso, 1 Margaret A. Tucker, 6 and Lynn R. Goldin 1 1Genetic Epidemiology Branch, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD; 2Cancer Genomics Research Laboratory, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD; 3Ad - vanced Biomedical Computing Center, Leidos Biomedical Research Inc.; Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, Frederick, MD; 4Westat, Inc., Rockville MD; 5Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD; and 6Human Genetics Program, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA ©2016 Ferrata Storti Foundation. This is an open-access paper. doi:10.3324/haematol.2015.135475 Received: August 19, 2015. Accepted: January 7, 2016. Pre-published: June 13, 2016. Correspondence: [email protected] Supplemental Author Information: NCI DCEG Cancer Sequencing Working Group: Mark H. Greene, Allan Hildesheim, Nan Hu, Maria Theresa Landi, Jennifer Loud, Phuong Mai, Lisa Mirabello, Lindsay Morton, Dilys Parry, Anand Pathak, Douglas R. Stewart, Philip R. Taylor, Geoffrey S. Tobias, Xiaohong R. Yang, Guoqin Yu NCI DCEG Cancer Genomics Research Laboratory: Salma Chowdhury, Michael Cullen, Casey Dagnall, Herbert Higson, Amy A. -

Association of KIR2DS4 and Its Variant KIR1D with Leukemia

Letters to the Editor 2129 Association of KIR2DS4 and its variant KIR1D with leukemia Leukemia (2008) 22, 2129–2130; doi:10.1038/leu.2008.108; comparison with healthy subjects. We included 90 adults published online 8 May 2008 with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML, n ¼ 31), acute myeloid leukemia ( n ¼ 38), and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (n ¼ 21) who were candidates for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell Natural killer (NK) cells are postulated to take part in innate transplantation. KIR2DS4n001 and KIR1D alleles were detected immunosurveillance against leukemia, contributing to both the according to previously described methodology5 in patients as disease control and clearance.1 A systematic review regarding well as in their HLA-matched related (n ¼ 31) or unrelated the role of NK cell receptors and their ligands in leukemia has (n ¼ 59) donors, serving as controls. Such selection of control recently been published by Verheyden and Demanet.1 group let us avoid potential bias resulting from the association of The activity of NK cells depends on the balance of activating HLA genotype with leukemia. All patients and donors were and inhibitory signals that are transmitted through respective Caucasoids. Patients and sibling donors were of Polish origin, receptors, including killer immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs). while the majority of unrelated donors were either Polish or HLA class I molecules are ligands for inhibitory KIRs, whereas German. As previously reported, the distribution of KIR genes ligands for their activating counterparts have not been well among these two populations is very similar.6 defined. As well, the physiological role of activating KIRs The frequencies of various allele combinations in patients, remains obscure and appears particularly intriguing in view of donors and population controls are listed in Table 1. -

ILT2/Cd85j/LILRB1/LIR-1)

Killer Cell Ig-Like Receptor-Dependent Signaling by Ig-Like Transcript 2 (ILT2/CD85j/LILRB1/LIR-1) This information is current as Sheryl E. Kirwan and Deborah N. Burshtyn of September 29, 2021. J Immunol 2005; 175:5006-5015; ; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.8.5006 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/175/8/5006 Downloaded from References This article cites 59 articles, 28 of which you can access for free at: http://www.jimmunol.org/content/175/8/5006.full#ref-list-1 Why The JI? Submit online. http://www.jimmunol.org/ • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication *average by guest on September 29, 2021 Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2005 by The American Association of Immunologists All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. The Journal of Immunology Killer Cell Ig-Like Receptor-Dependent Signaling by Ig-Like Transcript 2 (ILT2/CD85j/LILRB1/LIR-1)1 Sheryl E. Kirwan and Deborah N. Burshtyn2 Inhibitory killer cell Ig-like receptors (KIR) signal by recruitment of the tyrosine phosphatase Src homology region 2 domain- containing phosphatase-1 to ITIM. -

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Materials Supplemental Figure S1. Distinct difference in expression of 576 sensome genes comparing cortex versus microglia. (A) This heatmap shows all 576 sensome candidate genes ordered by DE and with the left column shows if the gene is present in the “Hickman et al. sensome” Supplemental Figure S2. Mouse sensome and human sensome genes categorized by group. (A) Bar graph showing the number of mouse and human sensome genes per group (Cell-Cell Interactions, Chemokine and related receptors, Cytokine receptors, ECM receptors, Endogenous ligands receptors, sensors and transporters, Fc receptors, Pattern recognition and related receptors, Potential sensors but no known ligands and Purinergic and related receptors). Supplementary Figure S3. Overlap of ligands recognized by microglia sensome (A) Overlap between the ligands of the receptors from respectively human and mouse core sensome was shown using Venn Diagrams. (B) Ligands of human and mouse receptors categorized in groups (Glycoproteins, Cytokines, Immunoglobulin, Amino acids, Carbohydrates, Electrolytes, Lipopeptides, Chemokines, Neuraminic acids, Nucleic acids, Receptors, Lipids, Fatty acids, Leukotrienes, Hormones, Steroids and Phospholipids) and spread of different groups shown as parts of whole again highlighting that the distribution of ligands what the human and mouse sensome genes can sense (Categorization of ligands in Supplementary Table S1). Supplementary Figure S4. Microglia core sensome expression during aging. (A) Two-log fold change of microglia core sensome genes in aging mice derived from Holtman et al. [12]. (B) Accelerated aging model (ERCC1), with impaired DNA repair mechanism, shows changes of microglia core sensome expression [12]. (C) Microglia core sensome expression during aging in human derived from Olah et al. -

Importance of HLA Class I Amino Acid Position 194 and LILRB1 Receptor

tics: O ne pe ge n o A n c u c e m s s m I Immunogenetics: Open access Grifoni, et al., Immunogenet open access 2016, 1:1 Editorial Open Access Importance of HLA Class I Amino Acid Position 194 and LILRB1 Receptor in HIV Disease Progression Alba Grifoni1 and Massimo Amicosante1,2* 1ProxAgen Ltd, Sofia, Bulgaria 2Department of Biomedicine and Prevention, University of Rome “Tor Vergata”, Rome, Italy *Corresponding author: Massimo Amicosante, Department of Biomedicine and Prevention, University of Rome “Tor Vergata”, Rome, Italy, Tel: 390672596202; Fax: 390672596202; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: March 26, 2016; Accepted date: March 28, 2016; Published date: March 31, 2016 Copyright: © 2016 Grifoni A, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Editorial HLA-B/LILRB1 interaction [13]. This is consistent with previous results showing a different binding capability of LILRB1 with HLA- HIV-specific T-cell response, and in particular CTL, plays a key role B*27:05 carrying different peptides [15]. in controlling HIV infection [1]. An increasing importance is currently recognised also to innate immune response, particularly the one In HIV infection expression of LILRB1 is increased respect to associated to NK cells and the interaction of its receptor with HLA healthy donor. Higher is HIV viremia, higher is LILRB1 expression class I molecules [2]. We have recently performed an immunogenetic [11,16]. The evaluation of patients developing primary HIV-1 infection study in a defined cohort of children infected during a hospital showed that a significant proportion of HIV-1 specific CD8 T cells outbreak with a monophyletic strain of HIV-1 [3], assessing the role of express LILRB1 and the expression increase over the time in these cells amino acid polymorphisms in HLA molecules [4,5].