The Art of “Including Art” in Animation: Dreamworks' Intertextual Games For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animating Failure

ChApter six Animating Failure enDing, Fleeing, surviving Who am I? Why a fox? Why not a horse, or a beetle, or a bald eagle? I’m saying this more as, like, existentialism, you know? Who am I? And how can a fox ever be happy without, you’ll forgive the expres- sion, a chicken in its teeth? —Fantastic Mr. Fox On the topic of animation, as on so many other topics, I disagree with Slavoj Žižek (2009), who, in an article on the link between capitalism and new forms of authoritarianism, offers up the ani- mated film Kung Fu Panda (2008) as an example of the kind of ideological sleight of hand that he sees as characteristic of both representative democracy and films for children. For Žižek, the fat and ungainly panda who accidently becomes a kung fu mas- ter is a figure that evokes George W. Bush or Silvio Berlusconi: by rising to the status of world champion without either talent or training, he masquerades as the little man who tries hard and succeeds, when in fact he is still a big man who is lazy but suc- ceeds anyway because the system is tipped in his favor. By em- bedding this narrative in a fluffy, cuddly panda bear film, Žižek implies, what looks like entertainment is actually propaganda. Žižek has managed to get a lot of mileage out of his reading of this film precisely because his “big” critiques of economy and world politics seem so hilarious when personified by a text sup- posedly as inconsequential as Kung Fu Panda. -

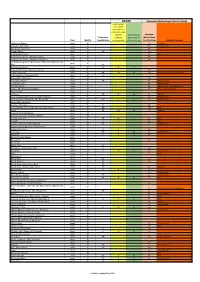

Kijkwijzer (Netherlands Classification) Some Content May Not Be Appropriate for Children This Age

ACCM Kijkwijzer (Netherlands Classification) Some content may not be appropriate for children this age. Parental Content is age Kijkwijzer Australian guidance appropriate for (Netherlands Year Netflix Classification recommended children this age Classification) Kijkwijzer reasons 1 Chance 2 Dance 2014 N 12+ Violence 3 Ninjas: Kick Back 1994 N 6+ Violence; Fear 48 Christmas Wishes 2017 N All A 2nd Chance 2011 N PG All A Christmas Prince 2017 N 6+ Fear A Christmas Prince: The Royal Baby 2019 N All A Christmas Prince: The Royal Wedding 2018 N All A Christmas Special: Miraculous: Tales of Ladybug & Cat 2016 N Noir PG A Cinderella Story 2004 N PG 8 13 A Cinderella Story: Christmas Wish 2019 N All A Dog's Purpose 2017 N PG 10 13 12+ Fear; Drugs and/or alcohol abuse A Dogwalker's Christmas Tale 2015 N G A StoryBots Christmas 2017 N All A Truthful Mother 2019 N PG 6+ Violence; Fear A Witches' Ball 2017 N All Violence; Fear Airplane Mode 2020 N 16+ Violence; Sex; Coarse language Albion: The Enchanted Stallion 2016 N 9+ Fear; Coarse language Alex and Me 2018 N All Saints 2017 N PG 8 10 6+ Violence Alvin and the Chipmunks Meet the Wolfman 2000 N 6+ Violence; Fear Alvin and the Chipmunks: The Road Chip 2015 N PG 7 8 6+ Violence; Fear Amar Akbar Anthony 1977 N Angela's Christmas 2018 N G All Annabelle Hooper and the Ghosts of Nantucket 2016 N PG 12+ Fear Annie 2014 N PG 10 13 6+ Violence Antariksha Ke Rakhwale 2018 N April and the Extraordinary World 2015 N Are We Done Yet? 2007 N PG 8 11 6+ Fear Arrietty 2010 N G 6 9+ Fear Arthur 3 the War of Two -

CLONES, BONES and TWILIGHT ZONES: PROTECTING the DIGITAL PERSONA of the QUICK, the DEAD and the IMAGINARY by Josephj

CLONES, BONES AND TWILIGHT ZONES: PROTECTING THE DIGITAL PERSONA OF THE QUICK, THE DEAD AND THE IMAGINARY By JosephJ. Beard' ABSTRACT This article explores a developing technology-the creation of digi- tal replicas of individuals, both living and dead, as well as the creation of totally imaginary humans. The article examines the various laws, includ- ing copyright, sui generis, right of publicity and trademark, that may be employed to prevent the creation, duplication and exploitation of digital replicas of individuals as well as to prevent unauthorized alteration of ex- isting images of a person. With respect to totally imaginary digital hu- mans, the article addresses the issue of whether such virtual humans should be treated like real humans or simply as highly sophisticated forms of animated cartoon characters. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. IN TR O DU C T IO N ................................................................................................ 1166 II. CLONES: DIGITAL REPLICAS OF LIVING INDIVIDUALS ........................ 1171 A. Preventing the Unauthorized Creation or Duplication of a Digital Clone ...1171 1. PhysicalAppearance ............................................................................ 1172 a) The D irect A pproach ...................................................................... 1172 i) The T echnology ....................................................................... 1172 ii) Copyright ................................................................................. 1176 iii) Sui generis Protection -

SHREK the MUSICAL Official Broadway Study Guide CONTENTS

WRITTEN BY MARK PALMER DIRECTOR OF LEARNING, CREATIVE AND MEDIA WIldERN SCHOOL, SOUTHAMPTON WITH AddITIONAL MATERIAL BY MICHAEL NAYLOR AND SUE MACCIA FROM SHREK THE MUSICAL OFFICIAL BROADWAY STUDY GUIDE CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 Welcome to the SHREK THE MUSICAL Education Pack! A SHREK CHRONOLOGY 4 A timeline of the development of Shrek from book to film to musical. SynoPsis 5 A summary of the events of SHREK THE MUSICAL. Production 6 Interviews with members of the creative team of SHREK THE MUSICAL. Fairy Tales 8 An opportunity for students to explore the genre of Fairy Tales. Feelings 9 Exploring some of the hang-ups of characters in SHREK THE MUSICAL. let your Freak flag fly 10 Opportunities for students to consider the themes and characters in SHREK THE MUSICAL. One-UPmanshiP 11 Activities that explore the idea of exaggerated claims and counter-claims. PoWer 12 Activities that encourage students to be able to argue both sides of a controversial topic. CamPaign 13 Exploring the concept of campaigning and the elements that make a campaign successful. Categories 14 Activities that explore the segregation of different groups of people. Difference 15 Exploring and celebrating differences in the classroom. Protest 16 Looking at historical protesters and the way that they made their voices heard. AccePtance 17 Learning to accept ourselves and each other as we are. FURTHER INFORMATION 18 Books, CD’s, DVD’s and web links to help in your teaching of SHREK THE MUSICAL. ResourceS 19 Photocopiable resources repeated here. INTRODUCTION Welcome to the Education Pack for SHREK THE MUSICAL! Increasingly movies are inspiring West End and Broadway shows, and the Shrek series, based on the William Steig book, already has four feature films, two Christmas specials, a Halloween special and 4D special, in theme parks around the world under its belt. -

The Uses of Animation 1

The Uses of Animation 1 1 The Uses of Animation ANIMATION Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of the rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon. Animators are artists who specialize in the creation of animation. Animation can be recorded with either analogue media, a flip book, motion picture film, video tape,digital media, including formats with animated GIF, Flash animation and digital video. To display animation, a digital camera, computer, or projector are used along with new technologies that are produced. Animation creation methods include the traditional animation creation method and those involving stop motion animation of two and three-dimensional objects, paper cutouts, puppets and clay figures. Images are displayed in a rapid succession, usually 24, 25, 30, or 60 frames per second. THE MOST COMMON USES OF ANIMATION Cartoons The most common use of animation, and perhaps the origin of it, is cartoons. Cartoons appear all the time on television and the cinema and can be used for entertainment, advertising, 2 Aspects of Animation: Steps to Learn Animated Cartoons presentations and many more applications that are only limited by the imagination of the designer. The most important factor about making cartoons on a computer is reusability and flexibility. The system that will actually do the animation needs to be such that all the actions that are going to be performed can be repeated easily, without much fuss from the side of the animator. -

ALPHABETICAL LIST of Dvds and Vts 9/6/2011 DVD a Mighty Heart

ALPHABETICAL LIST OF DVDs AND VTs 9/6/2011 DVD A Mighty Heart: Story of Daniel Pearl A Nurse I am – Documentary and educational film about nurses A Single Man –with Colin Firth and Julianne Moore (R) Abe and the Amazing Promise: a lesson in Patience (VeggieTales) Akeelah and the Bee August Rush - with Freddie Highmore, Keri Russell, Jonathan Rhys Meyers, Terrence Howard, Robin Williams Australia - with Hugh Jackman, Nicole Kidman Aviator (story of Howard Hughes - with Leonardo DiCaprio Because of Winn-Dixie Beethoven - with Charles Grodin, Bonnie Hunt Big Red Black Beauty Cats & Dogs Changeling - with Angelina Jolie Charlie and the Chocolate Factory - with Johnny Depp Charlie Wilson’s War - with Tom Hanks, Julie Roerts, Phil Seymour Hoffman Charlotte’s Web Chicago Chocolat - with Juliette Binoche, Judi Dench, Alfred Molina, Lena Olin & Johnny Depp Christmas Blessing - with Neal Patrick Harris Close Encounters of the Third Kind – with Richard Dreyfuss Date Night – with Steve Carell and Tina Fey (PG-13) Dear John – with Channing Tatum and Amanda Seyfried (PG-13) Doctor Zhivago Dune Duplicity - with Julia Roberts and Clive Owen Enchanted Evita Finding Nemo Finding Neverland Fireproof – with Kirk Cameron on Erin Bethea (PG) Five People You Meet in Heaven Fluke Girl With a Pearl Earring – with Colin Firth, Scarlett Johannson, Tom Wilkinson Grand Torino (with Clint Eastwood) Green Zone – with Matt Damon (R) Happy Feet Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince Hildalgo with Viggo Mortensen (PG13) Holiday, The – with Cameron Diaz, Kate Winslet, -

Federal Register/Vol. 80, No. 158/Monday, August 17, 2015/Notices

Federal Register / Vol. 80, No. 158 / Monday, August 17, 2015 / Notices 49269 and downloaded at this Justice 2015, Public Law 114–27. In accordance before January 1, 2014. If eligible under Department Web site: http:// with Section 405(a) of TAARA 2015, these requirements, OTAA will certify www.justice.gov/enrd/consent-decrees. which amended the Trade Act of 1974, the group of workers as eligible to apply We will provide a paper copy of the Public Law 93–618 (‘‘the Trade Act’’), for adjustment assistance under title II Consent Decree upon written request the Director of the Office of Trade of the Trade Act. and payment of reproduction costs. Adjustment Assistance, Employment Further, worker groups that did not Please mail your request and payment and Training Administration (OTAA) submit petitions between January 1, to: Consent Decree Library, U.S. DOJ— has taken the following action for 2014 and June 29, 2015, but wish to be petitions that were filed with the ENRD, P.O. Box 7611, Washington, DC considered under the group eligibility Secretary of Labor under section 221(a) 20044–7611. for workers based on the 2015 Program of the Trade Act on or after January 1, Please enclose a check or money order may file a new petition within 90 days for $5.00 (25 cents per page 2014, and before June 29, 2015, and are of enactment of the new 2015 law which reproduction cost) payable to the United identified in the Appendices to this was signed by President Barak Obama States Treasury. notice. OTAA has reopened investigations of on June 29, 2015. -

Fx Animation

ANIMAYO 2012 El Festival Internacional de Cine de Animación, Efectos Especiales y Videojuegos Animayo, que desde hace seis años enmarca la primera semana de mayo como la fecha referente del cine de animación y efectos especiales de nuestras islas, y que mantiene como centro neurálgico el CICCA, vuelve a atraer a la ciudad de Las Palmas de Gran Ca- naria las miradas de festivales, escuelas, profesionales y aficionados de todo el mundo. La organización de Animayo presenta su programación 2012, la que será su séptima edición, que contendrá toda una semana repleta de proyecciones interancionales, mas- ter class de autentico lujo, talleres, ponencias, multiactividades e invitados internacio- nales de excepción que se desplazan hasta nuestra isla para fomentar la educación, la cultura, la economía y la industria del cine. Durante Animayo el público canario y cada vez más, asistentes provenientes de toda Es- paña, volverán a tener la ocasión de hacer un recorrido por la más actualizada selección de trabajos de animación y efectos especiales de artistas de todo el mundo. Encabezado por su director y productor Damián Perea, y contando con el apoyo institu- cional del Cabildo de Gran Canaria, la Sociedad de Promoción Económica de Gran Cana- ria, El Gobierno de Canarias, El Ayuntamiento de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Canarias Cultura en Red, El Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional, La Obra Social de La Caja de Canarias y numerosas empresas colaboradoras como Domingo Aonso o NH Hoteles, en- tre otras, Animayo se sigue consolidando como uno de los festivales de mayor prestigio a nivel internacional. En los últimos años el reconocimiento de Animayo se ha visto reforzado por haber sido invitado de honor en otros eventos internacionales de animación como: Animaizon (Za- ragoza), El BAC (Barcelona), El museo Gouda (Holanda), El museo del CAAC (Sevilla), La Cal Arts (Los Ángeles) y por haber tenido la oportunidad de promocionarnos también en Festivales tan importantes como el de Annecy. -

Shrek Audition Monologues

Shrek Audition Monologues Shrek: Once upon a time there was a little ogre named Shrek, who lived with his parents in a bog by a tree. It was a pretty nasty place, but he was happy because ogres like nasty. On his 7th birthday the little ogre’s parents sat him down to talk, just as all ogre parents had for hundreds of years before. Ahh, I know it’s sad, very sad, but ogres are used to that – the hardships, the indignities. And so the little ogre went on his way and found a perfectly rancid swamp far away from civilization. And whenever a mob came along to attack him he knew exactly what to do. Rooooooaaaaar! Hahahaha! Fiona: Oh hello! Sorry I’m late! Welcome to Fiona: the Musical! Yay, let’s talk about me. Once upon a time, there was a little princess named Fiona, who lived in a Kingdom far, far away. One fateful day, her parents told her that it was time for her to be locked away in a desolate tower, guarded by a fire-breathing dragon- as so many princesses had for hundreds of years before. Isn’t that the saddest thing you’ve ever heard? A poor little princess hidden away from the world, high in a tower, awaiting her one true love Pinocchio: (Kid or teen) This place is a dump! Yeah, yeah I read Lord Farquaad’s decree. “ All fairytale characters have been banished from the kingdom of Duloc. All fruitcakes and freaks will be sent to a resettlement facility.” Did that guard just say “Pinocchio the puppet”? I’m not a puppet, I’m a real boy! Man, I tell ya, sometimes being a fairytale creature sucks pine-sap! Settle in, everyone. -

To Academy Oral Histories Marvin J. Levy

Index to Academy Oral Histories Marvin J. Levy Marvin J. Levy (Publicist) Call number: OH167 60 MINUTES (television), 405, 625, 663 ABC (television network) see American Broadcasting Company (ABC) ABC Circle Films, 110, 151 ABC Pictures, 84 A.I. ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE, 500-504, 615 Aardman (animation studio), 489, 495 AARP Movies for Grownups Film Festival, 475 Abagnale, Frank, 536-537 Abramowitz, Rachel, 273 Abrams, J. J., 629 ABSENCE OF MALICE, 227-228, 247 Academy Awards, 107, 185, 203-204, 230, 233, 236, 246, 292, 340, 353, 361, 387, 432, 396, 454, 471, 577, 606, 618 Nominees' luncheon, 348 Student Academy Awards, 360 Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences, 361-362, 411 Academy Board of Governors, 312, 342, 346-349, 357, 521 Academy Film Archive, 361, 388, 391, 468 Public Relations Branch, 342, 344, 348, 356 Visiting Artists Program, 614, 618 ACCESS HOLLYWOOD (television), 100, 365 Ackerman, Malin, 604 Activision, 544 Actors Studio, 139 Adams, Amy, 535 THE ADVENTURES OF HUCKLEBERRY FINN, 71, 458 THE ADVENTURES OF TINTIN, 126 Aghdashloo, Shohreh, 543 Aldiss, Brian, 502 Aldrich, Robert, 102, 107, 111 Alexander, Jane, 232, 237 Ali, Muhammad, 177 ALICE IN WONDERLAND (2010), 172, 396 ALIVE, 335 Allen, Debbie, 432 Allen, Herbert, 201, 205 Allen, Joan, 527-528 Allen, Karen, 318, 610 Allen, Paul, 403-404 Allen, Woody, 119, 522-523, 527 ALMOST FAMOUS, 525-526, 595 ALWAYS (1989), 32, 323, 326, 342, 549 Amateau, Rod, 133-134 Amazing Stories (comic book), 279 AMAZING STORIES (television), 278-281, 401 Amblimation, 327, 335-336, 338, 409-410 -

Creating Their Worlds

Skip to Content ? CAL POLY M A G A Z N E Home Past Issues Alumni Giving Contact Table of Contents Sum In This Editio n: Creating Their Worlds A Collective Vision Comes to Lif e Close Ties Between Cal Poly and Dream Works are Giving Alums the Chance to Make Movie Editor's Note Magic By JoAnn Lloyd The Apprentices Become the Masters Chris Gi bson hadn' t thought much about Around campus applying his comput er sci ence degree to a film career. Creating Their Worlds But a couple of Cal Poly computer science Green and Gold graphics courses opened his eyes and, he said, "unraveled some mysteries of movie-m aking." Citizen Science Then he saw " How to Train Your Dragon," t he 2010 hit movie from DreamWorks Ani mation. Hard Work Under Pressure And it clicked . Class Notes "Some of the things I saw on the screen i n that movi e really inspired me," said Gibson (B.S., cal Poly students polish oft their graphics project in a spring class. (Photos by Br ittany App) Their dassroom, the World M .S., Computer Science, 2011). " I reali zed I w anted t o work on a Drea m Works movie." University News He applied to t he company, and two years lat er dream became reality. Gibson was cred it ed as "technical d irect o r" on the November 2012 Closing Thoughts rel ease "Rise of t he Guard ians," a Gol den Globe nominee for best animated feature. This year, he not ched his second cred it w it h the spring re lease "The Croods.11 Gibson i s one of t hree Cal Poly Computer Science alum s who helped bring " Rise of the Gua rdians" to t he big screen and among an even larger group of grads helping to make movie magic w it h Drea mWorks. -

Irradiance Caching at Dreamworks

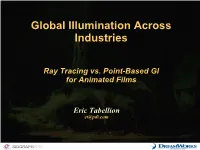

Global Illumination Across Industries Ray Tracing vs. Point-Based GI for Animated Films Eric Tabellion [email protected] Introduction • Global Illumination (GI) usage at DreamWorks Animation – Bounce lighting – Ambient occlusion – HDR Environment map lighting (IBL) – Used on many films since “Shrek 2” • Used in a variety of shots • Various characters, props and environments • Global Illumination system – Using Ray Tracing and Irradiance Caching (IC) • [Tabellion and Lamorlette 2004] • [Krivanek et al. 2008] – Using point-based GI • [Christensen 2008] Direct Lighting Only Direct + Indirect Lighting Example: “How To Train Your Dragon ” Example: “How To Train Your Dragon ” Example: “Shrek Forever After” GI in Animated Film Production • Requirements: – High Quality • No noise, buzzing or popping – Artistic control • Offer physically correct starting point • Let the user tweak shaders further – Good shader integration – Speedy interaction • Add bounce cards to control lighting • Apply localized filters to GI – Scene complexity • Scene complexity is unbounded (more or less tuned) GI in Animated Film Production • Multi-department Impact: – Modelling & Animation • Geometry with bad contact / penetrations – Surfacing • Account for GI as a lighting scenario • Define bouncing characteristics – FX • Effects do illuminate and occlude – Lighting • GI not always intuitive – Light is coming from everywhere • GI produces simpler lighting rigs • Propagates well to other shots / sequences Ray-Tracing-Based GI System Overview • Micropolygon Deep Frame Buffer Renderer