The Sonata for Piano and Violin Perfected

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comparative Analysis of the Six Duets for Violin and Viola by Michael Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE SIX DUETS FOR VIOLIN AND VIOLA BY MICHAEL HAYDN AND WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART by Euna Na Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May 2021 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Frank Samarotto, Research Director ______________________________________ Mark Kaplan, Chair ______________________________________ Emilio Colón ______________________________________ Kevork Mardirossian April 30, 2021 ii I dedicate this dissertation to the memory of my mentor Professor Ik-Hwan Bae, a devoted musician and educator. iii Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................ iv List of Examples .............................................................................................................................. v List of Tables .................................................................................................................................. vii Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: The Unaccompanied Instrumental Duet... ................................................................... 3 A General Overview -

César Franck's Violin Sonata in a Major

Honors Program Honors Program Theses University of Puget Sound Year 2016 C´esarFranck's Violin Sonata in A Major: The Significance of a Neglected Composer's Influence on the Violin Repertory Clara Fuhrman University of Puget Sound, [email protected] This paper is posted at Sound Ideas. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/honors program theses/21 César Franck’s Violin Sonata in A Major: The Significance of a Neglected Composer’s Influence on the Violin Repertory By Clara Fuhrman Maria Sampen, Advisor A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements as a Coolidge Otis Chapman Scholar. University of Puget Sound, Honors Program Tacoma, Washington April 18, 2016 Fuhrman !2 Introduction and Presentation of My Argument My story of how I became inclined to write a thesis on Franck’s Violin Sonata in A Major is both unique and essential to describe before I begin the bulk of my writing. After seeing the famously virtuosic violinist Augustin Hadelich and pianist Joyce Yang give an extremely emotional and perfected performance of Franck’s Violin Sonata in A Major at the Aspen Music Festival and School this past summer, I became addicted to the piece and listened to it every day for the rest of my time in Aspen. I always chose to listen to the same recording of Franck’s Violin Sonata by violinist Joshua Bell and pianist Jeremy Denk, in my opinion the highlight of their album entitled French Impressions, released in 2012. After about a month of listening to the same recording, I eventually became accustomed to every detail of their playing, and because I had just started learning the Sonata myself, attempted to emulate what I could remember from the recording. -

This Paper Is a Revised Version of My Article 'Towards A

1 This paper is a revised version of my article ‘Towards a more consistent and more historical view of Bach’s Violoncello’, published in Chelys Vol. 32 (2004), p. 49. N.B. at the end of this document readers can download the music examples. Towar ds a different, possibly more historical view of Bach’s Violoncello Was Bach's Violoncello a small CGda Violoncello “played like a violin” (as Bach’s Weimar collegue Johann Gottfried Walther 1708 stated)? Lambert Smit N.B. In this paper 18 th century terms are in italics. Introduction Bias and acquired preferences sometimes cloud people’s views. Modern musicians’ fondness of their own instruments sometimes obstructs a clear view of the history of each single instrument. Some instrumentalists want to defend the territory of their own instrument or to enlarge 1 it. However, in the 18 th century specialization in one instrument, as is the custom today, was unknown. 2 Names of instruments in modern ‘Urtext’ editions can be misleading: in the Neue Bach Ausgabe the due Fiauti d’ Echo in Bach’s score of Concerto 4 .to (BWV 1049) are interpreted as ‘Flauto dolce’ (=recorder, Blockflöte, flûte à bec), whereas a Fiauto d’ Echo was actually a kind of double recorder, consisting of two recorders, one loud and one soft. (see internet and Bachs Orchestermusik by S. Rampe & D. Sackmann, p. 279280). 1 The bassoon specialist Konrad Brandt, however, argues against the habit of introducing a bassoon in every movement in Bach’s church music where oboes are played (the theory ‘wo Oboen, da auch Fagott’) BachJahrbuch '68. -

WALTON, William Turner Piano Quartet / Violin Sonata / Toccata (M

WALTON, William Turner Piano Quartet / Violin Sonata / Toccata (M. Jones, S.-J. Bradley, T. Lowe, A. Thwaite) Notes to performers by Matthew Jones Walton, Menuhin and ‘shifting’ performance practice The use of vibrato and audible shifts in Walton’s works, particularly the Violin Sonata, became (somewhat unexpectedly) a fascinating area of enquiry and experimentation in the process of preparing for the recording. It is useful at this stage to give some historical context to vibrato. As late as in Joseph Joachim’s treatise of 1905, the renowned violinist was clear that vibrato should be used sparingly,1 through it seems that it was in the same decade that the beginnings of ‘continuous vibrato use’ were appearing. In the 1910s Eugene Ysaÿe and Fritz Kreisler are widely credited with establishing it. Robin Stowell has suggested that this ‘new’ vibrato began to evolve partly because of the introduction of chin rests to violin set-up in the early nineteenth century.2 I suspect the evolution of the shoulder rest also played a significant role, much later, since the freedom in the left shoulder joint that is more accessible (depending on the player’s neck shape) when using a combination of chin and shoulder rest facilitates a fluid vibrato. Others point to the adoption of metal strings over gut strings as an influence. Others still suggest that violinists were beginning to copy vocal vibrato, though David Milsom has observed that the both sets of musicians developed the ‘new vibrato’ roughly simultaneously.3 Mark Katz persuasively posits the idea that much of this evolution was due to the beginning of the recording process. -

The Scottish Viola a Tribute to Watson Forbes

NI 6180 The Scottish Viola A tribute to WAtson Forbes For further information please visit MArtin outrAM viola www.martinoutram.com www.wyastone.co.uk JuliAn rolton piano The Scottish Viola A tribute to WAtson Forbes As an accompanist he recorded an piano trios entitled Borderlands on Campion Pietro Nardini (arr Forbes/Richardson): Concerto in G minor acclaimed CD of Russian song with Cameo which attracted exceptional reviews. 1. Allegro moderato 4:28 the mezzo-soprano Helen Lawrence in The Chagall Trio has appeared at festivals 2. Andante affettuoso 2:57 3. Allegretto 2:35 celebration of Pushkin’s bi-centenary. throughout Britain, broadcasts on BBC He has appeared with Richard Jackson Radio 3 and has given premieres of works Robin Orr: Sonata 4. Introduction and Fugue 5:01 in the Almeida Opera Festival and, with by Nicholas Maw, David Matthews and Philip 5. Elegy 4:24 Mary Wiegold, performed a programme Grange. During the Royal Academy of Art’s 6. Scherzetto 1:55 of songs by Howard Skempton in the Chagall exhibition, “Love and the Stage”, 7. Finale 4:51 Aldeburgh Festival. He regularly plays for they were invited to present a programme of Alan Richardson: Sonata the master-classes of such eminent singers music and words celebrating the life of their 8. Poco lento - Allegro 6:17 as Galina Vishnevskaya, Phyllis Bryn-Julson namesake. With the actor Samuel West, the 9. Molto vivace: leggiero e volante 2:24 10. Lento 7:06 and Anthony Rolfe Johnson at the Snape Trio repeated this programme in the Wigmore 11. Allegro energico 4:02 Maltings. -

An Exploration of Violin Repertoire from the Baroque Era to Present Day by Christina M. Adams a Dissertation

Versatile Violin: An Exploration of Violin Repertoire from the Baroque Era to Present Day by Christina M. Adams A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts (Music: Performance) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor Aaron Berofsky, Chair Professor Richard Aaron Professor Evan Chambers Professor Colleen Conway Assistant Professor Kathryn Votapek Professor Terry Wilfong Christina M. Adams [email protected] ORCID ID: 0000-0002-1470-9921 © Christina M. Adams 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge my professors for their wisdom and guidance, as this project would not have been possible without them; My parents, Liz and John, for their endless support; And my husband, Sungho, for his constant encouragement. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii LIST OF FIGURES iv ABSTRACT v RECITAL 1 1 Recital 1 Program 1 Recital 1 Program Notes 2 RECITAL 2 Recital 2 Program 11 Recital 2 Program Notes 12 RECITAL 3 Recital 3 Program 20 Recital 3 Program Notes 21 BIBLIOGRAPHY 30 iii LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page 1.1 String Quartet (1931)- Andante 8 2.1 “The Later Folia” 13 2.2 “Staccato-Legato” 14 2.3 “The Devil’s Trill” 19 3.1 Sonata no. 2- “Blues” 25 3.2 The Fire Hose Reel- “Siren” 26 3.3 “Shuffle Step” from String Circle 28 iv ABSTRACT Three violin recitals were given in lieu of a written dissertation. The selections in these recitals explore the violin’s versatility. The first recital Wonder Women: Works by Female Composers was comprised of works by Louise Farrenc, Lili Boulanger, Augusta Read Thomas, Chihchun Chi-sun Lee, and Ruth Crawford Seeger. -

F113017 5Pm Violin Viola Studio Recital PROGRAM

Williams College Department of Music Violin and Viola Studio Recital with Students of Muneko Otani and Ah Ling Neu Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756 – 1791) Violin Sonata KV 293B E flat Major Allegro Rondeau – Andante grazioso Andrea Alvarez ‘20, violin; Julia Choi ‘20, piano Johann Sebastian Bach (1685 – 1750) Chaconne – Solo violin Lucca Delcompare ‘20, violin Mikhail Glinka (1804 – 1857) Sonata for Viola and Piano I. Allegro Moderato Kenneth Han ‘21, viola; Bernard Rose, piano Battista Viotti (1755 – 1824) Violin Concerto op. 23 Giovanni III. Allegro Fiona Keller ‘21, violin; Hannah Chang ‘20, piano Johann Sebastian Bach Gamba Sonata No. 1 in G Major I. Adagio II. Allegro Ahna Pearson ‘20, viola; Bernard Rose, piano Max Bruch (1838 – 1920) Violin Concerto No. 1 op. 26 II. Adagio Louisa Nyhus ‘20, violin; Stephen Ai ‘18, piano Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Violin concerto in G Major KV 216 III. Rondeau Sophie Lu ‘19, violin; Qian Yang ‘19, piano Rebecca Clarke (1886 – 1979) Sonata for Viola and Piano I. Impetuoso Aria Kim ‘19, viola; Bernard Rose, piano Johannes Brahms (1831 – 1897) Sonata for Violin and Piano No. 2, op. 100, I. Allegro amabile Teresa Yu ‘20, violin; Qian Yang ‘19, piano Johann Sebastian Bach Suite in D Minor Gigue Franz Liszt (1811 – 1886) Forgotten Romance Ethan Lopes ‘20, viola; Bernard Rose, piano Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 – 1827) Romance for the violin, op. 50 in F Major Kevin Zhou ‘20, violin; Alex Medieros ‘20, piano Johannes Brahms Sonata for Viola in E Flat Major, op. 120 No. 2 I. Allegro amabile Dawn Wu ‘18, viola; Bernard Rose, piano Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872 – 1958) “The Lark Ascending” Abigail Soloway ‘18, violin; Stephen Ai ‘18, piano Paul Hindemith (1895 – 1963) Viola solo sonata op. -

Verklarte Nacht ("Transfigured Night") in D Minor, Op

S:he Jl,cademy o/ St. 511a1itin in the ~efds Chamhe'l Gnsembfe_ KENNETH SILLITO, LEADER KENNETH SILLITO, VIOLIN ROBERT SMISSEN, VIOLA HARVEY DE SOUZA, VIOLIN DUNCAN FERGUSON, VIOLA MARTIN BURGESS, VIOLIN STEPHEN ORTON, CELLO JAN SCHMOLCK, VIOLIN JOHN HELEY, CELLO TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 15, 2005 -PROGRAM "Innocent Ear" The ensemble will play a work unannounced, and invite the audience to guess composer/work with CDs as a prize. Verklarte Nacht ("Transfigured Night") in D Minor, Op. 4 (1905) ARNOLD SCHOENBERG (1874-1951) - INTERMISSION- Octet for Strings in E-flat Major, Op. 20 (1825) FELIX MENDELSSOHN (1809-184 7) Allegro moderato, ma con fuoco Andante Scherzo (Allegro leggierissimo) Presto THIS PROGRAM HAS BEEN PARTIALLY UNDERWRITTEN BY THE GE NEROSITY OF AN ANONYMOUS DONOR IN HONOR OF SHIRLEY AND DAVID TOOMIM. Please turn off all cellphones, pagers and chiming watches. Also, taking photographs (with cameras, phones or any media device) or making recordings is strictly prohibited. Thank you. ARNOLD SCHOENBERG (1874-1951) Verklarte Nacht (Transfigured Night) Most people associate Arnold Schoenberg with development of the "twelve-tone" sys tem of musical composition. However, one of his most popular works, Verklarte Nacht, was composed early in his career (1899) at the age of twenty-five, before his experiments in atonality were evident. Though primarily a self-taught composer, Schoenberg admits to having been greatly influenced by Brahms and Wagner during this period. Verklarte Nacht was unusual in that it was a tone poem composed for a chamber ensemble (string sextet). It was based on a poem written in 1896 by Richard Dehmel, whose work Schoenberg particularly admired. -

Violin Syllabus / 2013 Edition

VVioliniolin SYLLABUS / 2013 EDITION SYLLABUS EDITION © Copyright 2013 The Frederick Harris Music Co., Limited All Rights Reserved Message from the President The Royal Conservatory of Music was founded in 1886 with the idea that a single institution could bind the people of a nation together with the common thread of shared musical experience. More than a century later, we continue to build and expand on this vision. Today, The Royal Conservatory is recognized in communities across North America for outstanding service to students, teachers, and parents, as well as strict adherence to high academic standards through a variety of activities—teaching, examining, publishing, research, and community outreach. Our students and teachers benefit from a curriculum based on more than 125 years of commitment to the highest pedagogical objectives. The strength of the curriculum is reinforced by the distinguished College of Examiners—a group of fine musicians and teachers who have been carefully selected from across Canada, the United States, and abroad for their demonstrated skill and professionalism. A rigorous examiner apprenticeship program, combined with regular evaluation procedures, ensures consistency and an examination experience of the highest quality for candidates. As you pursue your studies or teach others, you become not only an important partner with The Royal Conservatory in the development of creativity, discipline, and goal- setting, but also an active participant, experiencing the transcendent qualities of music itself. In a society where our day-to-day lives can become rote and routine, the human need to find self-fulfillment and to engage in creative activity has never been more necessary. -

The Rebecca Clarke Society Newsletter

The Rebecca Clarke Society Newsletter February 2012 Volume 7 From our President , Liane Curtis Dear Friends and Supporters! Clarke's music from all far -flung We have not produced a corners of the globe: Japan, newsletter for some time. That Australia, South Africa, and The is not due to a lack of news, but Rebecca Clarke Society rather the opposite! So much supported performances and has been going on that it is hard Master Classes featuring her to stay on top of everything. music in China. More performances of the Last year we celebrated the orchestration of Clarke's Viola 125 th anniversary of Clarke's Sonata have taken place – in birth, so it seemed important to Bartlesville, OK; Stockholm, get a newsletter out and get Sweden; Eskişehir, Turkey (the back in touch with our many Only known photo of Anadolu Symphony Orchestra supporters (and welcome new Clarke playing the viola, with soloist Esra Pehlivanli ), and ones as well!). from the mid-1920s the Chamber Orchestra of the We look forward to hearing Springs in Colorado Springs, CO your insights, news, and ideas (with Cathy Hanson, viola) and for the newsletter (should we Contents in this newsletter we report on have a newsletter? Or should two upcoming performances. we just be tweeting???), as well Performances of the Sonata for Viola and Orchestra 1 We continue to receive as ideas for the Clarke Society. reports of performances of Please enjoy! A Conversation with Michael Beckerman 2 Clarke featured in China 4 West -Coast Premiere of Clarke’s Viola Sonata with Orchestra Problems of Clarke’s estate examined in article 4 The North State Symphony will give by Maestro Kyle Wiley Pickett ) is the the West Coast Premiere of Rebecca third orchestra to perform Ruth Clarke’s Sonata for Viola and Lomon’s orchestration of the Clarke. -

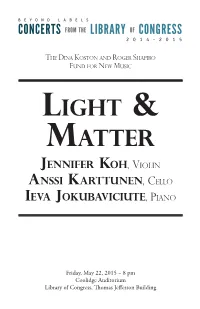

Light & Matter

THE DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO fUND fOR nEW mUSIC LIGHT & MATTER JENNIFER KOH, vIOLIN ANSSI KARTTUNEN, cELLO IEVA JOKUBAVICIUTE, pIANO Friday, May 22, 2015 ~ 8 pm Coolidge Auditorium Library of Congress, Thomas Jefferson Building THE DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO FUND FOR NEW MUSIC Endowed by the late composer and pianist Dina Koston (1929-2009) and her husband, prominent Washington psychiatrist Roger L. Shapiro (1927-2002), the DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO FUND FOR NEW MUSIC supports commissions, contemporary music and its performers. Presented in association with the European Month of Culture Part of National Chamber Music Month Please request ASL and ADA accommodations five days in advance of the concert at 202-707-6362 or [email protected]. Latecomers will be seated at a time determined by the artists for each concert. Children must be at least seven years old for admittance to the concerts. Other events are open to all ages. • Please take note: Unauthorized use of photographic and sound recording equipment is strictly prohibited. Patrons are requested to turn off their cellular phones, alarm watches, and any other noise-making devices that would disrupt the performance. Reserved tickets not claimed by five minutes before the beginning of the event will be distributed to stand-by patrons. Please recycle your programs at the conclusion of the concert. The Library of Congress Coolidge Auditorium Friday, May 22, 2015 — 8 pm THE DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO fUND fOR nEW mUSIC LIGHT & MATTER JENNIFER KOH, vIOLIN ANSSI KARTTUNEN, cELLO IEVA JOKUBAVICIUTE, pIANO • Program CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862–1918) Sonate pour Violoncelle et Piano (1915) Prologue: Lent, Sostenuto e molto risoluto–(Agitato)–au Mouvt (largement déclamé)–Rubato–au Mouvt (poco animando)–Lento Sérénade: Modérément animé–Fuoco–Mouvt–Vivace–Meno mosso poco– Rubato–Presque lent–1er Mouvt–au Mouvt– Finale: Animé, Léger et nerveux–Rubato–1er Mouvt–Con fuoco ed appassionato–Lento. -

Violin, I the Instrument, Its Technique and Its Repertory in Oxford Music Online

14.3.2011 Violin, §I: The instrument, its techniq… Oxford Music Online Grove Music Online Violin, §I: The instrument, its technique and its repertory article url: http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com:80/subscriber/article/grove/music/41161pg1 Violin, §I: The instrument, its technique and its repertory I. The instrument, its technique and its repertory 1. Introduction. The violin is one of the most perfect instruments acoustically and has extraordinary musical versatility. In beauty and emotional appeal its tone rivals that of its model, the human voice, but at the same time the violin is capable of particular agility and brilliant figuration, making possible in one instrument the expression of moods and effects that may range, depending on the will and skill of the player, from the lyric and tender to the brilliant and dramatic. Its capacity for sustained tone is remarkable, and scarcely another instrument can produce so many nuances of expression and intensity. The violin can play all the chromatic semitones or even microtones over a four-octave range, and, to a limited extent, the playing of chords is within its powers. In short, the violin represents one of the greatest triumphs of instrument making. From its earliest development in Italy the violin was adopted in all kinds of music and by all strata of society, and has since been disseminated to many cultures across the globe (see §II below). Composers, inspired by its potential, have written extensively for it as a solo instrument, accompanied and unaccompanied, and also in connection with the genres of orchestral and chamber music. Possibly no other instrument can boast a larger and musically more distinguished repertory, if one takes into account all forms of solo and ensemble music in which the violin has been assigned a part.