Eotm the Agony and the Ecstasy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Please Forward the Following Wpg

PLEASE FORWARD THE FOLLOWING AmerUs Group BNY MELLON WPG/MATCHING GIFT CHECKS TO JDRF FOR PROCESSING (Attn: WPG DEPT.) AMGEN BOEING Anheuser-Busch Cos. Inc. BOEING COMPANY Below is a partial listing of companies that participate in Workplace Giving/Matching AOL Time Warner Foundation Booz Allen Hamilton Gift campaigns. Based on our most recently compiled data; the companies APPLE BOOZ-ALLEN-HAMILTION highlighted in pink offer web-based ARAMARK Borden Foundation portals that enable recipient agencies to view their payment history and donor ARAMARK Corp. BP Amoco information online. ARCELORMITTAL BP FOUNDATION * A * ARCELORMITTAL MATCHING GIFT Bridgestone/Firestone Inc. ABBOTT LABORATORIES PROGRAM Brink's Co. ARCO Accenture BRISTOL-MYER ASSURANT ADOBE BRISTOL-MYERS SQUIBB CO. Assurant Health Foundation ADOBE SYSTEMS INC Brown & Williamson Tobacco AT&T FOUNDATION AETNA AT&T UNITED WAY EMPLOYEE GIVING * C * AGILENT TECHNOLOGIES FOUNDATION CAMPAIGN Cable One ALBEMARLE Avery Dennison Corp. CADENCE ALBERMARLE FOUNDATION Avon Products Inc. CAMG (CA TECHNOLOGIES) Alcoa * B * Campbell Soup Foundation ALLIANCE BERNSTEIN BAE SYSTEM Cardinal Health ALLIANT ENERGY BANK OF AMERICA CARDINAL HEALTH FOUNDTION, INC. ALLSTATE BANK OF AMERICA - UNITED WAY CAMPAIGN CARMAX ALLSTATE (THE GIVING CAMPAIGN) BANK OF AMERICA UNITED WAY Caterpillar Foundation Allstate Foundation BANK OF NY MELLON Charles Schwab American Airlines BANK OF THE WEST CHEVRON AMERICAN CHARITIES Bank One Chiquita Brands International AMERICAN EXPRESS Barclays Capital Chrysler Corporation Fund AMERICAN EXPRESS GIFT MATCHING BAXTER EMPLOYEE GIVING CAMPAIGN CIGNA CIVAL AFFAIRS SPONSORSHIP AMERICAN EXPRESS GIFT MATCHING PROGRAM Baxter Healthcare CIGNA Foundation AMERICAN EXPRESS GIVE2GETHER BAXTER INTERNATIONAL FDT Cingular Wireless CAMPAIGN Best Foods Circuit City American Standard Inc. Bestfoods American States Insurance Co. -

The Link Between Drugs and Music Explained by Science 25 January 2018, by Ian Hamilton, Harry Sumnall and Suzi Gage

The link between drugs and music explained by science 25 January 2018, by Ian Hamilton, Harry Sumnall And Suzi Gage two key compounds in cannabis, tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiols, influence the desire for music and its pleasure. Cannabis users reported that they experienced greater pleasure from music when they used cannabis containing cannabidiols than when these compounds were absent. Listening to music – without the influence of drugs – is rewarding, can reduce stress (depending upon the type of music listened to) and improve feelings of belonging to a social group. But research Credit: Henny van Roomen/Shutterstock.com suggests that some drugs change the experience of listening to music. Clinical studies that have administered LSD to For centuries, musicians have used drugs to human volunteers have found that the drug enhance creativity and listeners have used drugs enhances music-evoked emotion, with volunteers to heighten the pleasure created by music. And the more likely to report feelings of wonder, two riff off each other, endlessly. The relationship transcendence, power and tenderness. Brain between drugs and music is also reflected in lyrics imaging studies also suggest that taking LSD while and in the way these lyrics were composed by listening to music, affects a part of the brain leading musicians, some of whom were undoubtedly to an increase in musically inspired complex visual influenced by the copious amounts of heroin, imagery. cocaine and "reefer" they consumed, as their songs sometimes reveal. Pairing music and drugs Acid rock would never have happened without Certain styles of music match the effects of certain LSD, and house music, with its repetitive 4/4 beats, drugs. -

About Emotions There Are 8 Primary Emotions. You Are Born with These

About Emotions There are 8 primary emotions. You are born with these emotions wired into your brain. That wiring causes your body to react in certain ways and for you to have certain urges when the emotion arises. Here is a list of primary emotions: Eight Primary Emotions Anger: fury, outrage, wrath, irritability, hostility, resentment and violence. Sadness: grief, sorrow, gloom, melancholy, despair, loneliness, and depression. Fear: anxiety, apprehension, nervousness, dread, fright, and panic. Joy: enjoyment, happiness, relief, bliss, delight, pride, thrill, and ecstasy. Interest: acceptance, friendliness, trust, kindness, affection, love, and devotion. Surprise: shock, astonishment, amazement, astound, and wonder. Disgust: contempt, disdain, scorn, aversion, distaste, and revulsion. Shame: guilt, embarrassment, chagrin, remorse, regret, and contrition. All other emotions are made up by combining these basic 8 emotions. Sometimes we have secondary emotions, an emotional reaction to an emotion. We learn these. Some examples of these are: o Feeling shame when you get angry. o Feeling angry when you have a shame response (e.g., hurt feelings). o Feeling fear when you get angry (maybe you’ve been punished for anger). There are many more. These are NOT wired into our bodies and brains, but are learned from our families, our culture, and others. When you have a secondary emotion, the key is to figure out what the primary emotion, the feeling at the root of your reaction is, so that you can take an action that is most helpful. . -

MDMA and Sexual Behavior

Note: This is a pre-copy-editing, author-produced PDF of an article accepted for publication in Substance Use & Misuse following peer review. The definitive publisher-authenticated version [McElrath K (2005) MDMA and sexual behavior: ecstasy users’ perceptions about sexuality and sexual risk, Substance Use & Misuse, 40:9, 1461-1477] is available online at http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~db=all~content=g714012467 MDMA and Sexual Behavior: Ecstasy Users’ Perceptions About Sexuality and Sexual Risk KAREN MCELRATH School of Sociology and Social Policy, Belfast, Ireland Published in Substance Use & Misuse,(2005) 40:9,1461—1477 This study examines the relationship between MDMA (Ecstasy), sexual behavior, and sexual risk taking. The sample consisted of 98 current and former users of MDMA. Several strategies were utilized to recruit respondents and data were collected through in-depth interviews during 1997 and 1998. The majority of respondents had used MDMA during the 6-month period prior to the interview and a large percentage had consumed the drug on 100 occasions or more. Most respondents reported feelings of emotional closeness while consuming MDMA but without the desire for penetrative sex. Others, however, reported that MDMA increased sexual arousal and some respondents (in particular gay and bisexual females) had used MDMA specifically for sexual enhancement. Sexual risk taking (e.g., having multiple partners, engaging in sex without a condom) was prevalent among respondents who did engage in sexual activity during MDMA episodes. Explanations for the findings are offered and implications for prevention/intervention are discussed. Keywords MDMA; ecstasy; sexual behavior Introduction Although a patent for 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) was issued in 1914 (Shulgin, 1986), “recreational”a use of the drug did not surface until the 1970s and 1980s, and for the most part was restricted to selected regions in the U.S. -

Companies in Texas That Match Financial Donations

COMPANIES IN TEXAS THAT MATCH FINANCIAL DONATIONS Abbott Laboratories Avery Dennison Chubb Group/Chubb & Sons Adobe Systems Avon Products (Federal Insurance) ADP Ball Cigna Advanced Micro Devices Bank One Dallas Circuit City Stores Aetna BankAmerica Cisco Systems AG Communication Systems Bankers Trust CIT Group Air & Water Technologies Baroid Citgo Petroleum Air Products & Chemicals BASF Citicorp/Citibank N.A. Albertson’s Baxter Citizens Ban Alco Standard Bechtel CJT Enterprises Alcoa Becton Dickinson Clarcor Alex Brown & Sons Beecham SmithKline Clark, Klein & Beaumont Allegheny Ludlum Bell & Howell Clorox Allstate BellSouth Coca-Cola Amcast Industrial Bemis Colgate-Palmolive American Electric Power Beneficial Comerica American Express BetzDearborn Computer Associates Intl American General Finance BF Goodrich Conoco American Home Products Bituminous Casualty Container American Honda Motor Bloomingdale’s Continental Airlines American Intl Group Boeing Continental Corp Insurance American National Bank & Trust Borden Cooper Industrial American Standard Borg-Warner Cooper Tire & Rubber American States Insurance BP America Corning Amerisure Companies Brenco Cray Research Ameritech Bridgestone/Firestone Credit Suisse AMI Bristol-Myers Squibb Crowe Horwath LLP Amoco Brunswick Crum & Foster AMP BT Cummins Engine Analog Devices Budget Rent-A-Car CUNA Group Andersons Management Bunge Cytec Industries Anheuser-Busch Burlington Northern Dain Bosworth/IFG A.O. Smith Cabot Darden Restaurants Aon Campbell’s Soup Datatel Apache Canada Ltd Candle DDB -

Concise Encyclopedia of the Great Recession, 2007-2010

THE CONCISE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF THE GREAT RECESSION 2007–2010 Jerry M. Rosenberg The Scarecrow Press, Inc. Lanham • Toronto • Plymouth, UK 2010 Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 http://www.scarecrowpress.com Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom Copyright © 2010 by Jerry M. Rosenberg All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rosenberg, Jerry Martin. The concise encyclopedia of the great recession 2007–2010 / Jerry M. Rosenberg. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8108-7660-6 (hardback : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8108-7661-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8108-7691-0 (ebook) 1. Financial crises—United States—History—21st century—Dictionaries. 2. Recessions—United States—History—21st century—Dictionaries. 3. Financial institutions—United States—History—21st century—Dictionaries. I. Title. HB3743.R67 2010 330.9'051103—dc22 2010004133 ϱ ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed in the United States of America For Ellen Celebrating fifty years of love and adventure. She is my primary motivation. As a lifelong partner, Ellen keeps me spirited and vibrant. -

YOUR DONATION to PHCA Ashland Bellsouth Corp

Argonaut Group. Bass, Berry and Sims, PLC Butler Manufacturing Co. Ariel Capital Management Baxter International Cadence Design Systems Aristokraft Bay Networks Calex Manufacturing Co. Arkema BEA Systems Calpine, Corp. Armstrong World Industries Bechtel Group CambridgeSoft Armtek, Corp. Becton Dickinson and Co. Campbell Soup Foundation Arrow Electronics Belden Wire and Cable Co. Canadian Pacific Railway YOUR DONATION to PHCA Ashland BellSouth Corp. Capital Group Cos. Aspect Telecommunications Bemis Co. Capital One Services Companies with Matching Gift Programs Associates Corp. of North BeneTemps Cardinal Health (contact your HR Dept. for instructions) America L.M. Berry and Co. Cargill Assurant Health BHP Minerals International Carnegie Corp. of New York Astoria Federal Savings Binney and Smith Castrol North America AAI Corp. Amerada Hess Corp. AstraZenca Bituminous Casualty Corp. Carson Products Co. Abbott Laboratories Ameren Corp. AT&T Black and Decker Corp. Catalina Marketing, Corp. ABN AMBRO North American Electric Power Atlantic City Electric Co. Blount Foundation Catepillar America American Express Co. Atlantic Data Services Blue Bell Central Illinois Light Co. Accenture American General Corp. Autodest BMC Industries Chesapeake Corp. ACF Industries American Honda Motor Corp. Automatic Data Processing BMO Financial Group, US ChevronTexaco Corp. Acuson American International Group AVAYA BOC Group Chicago Mercantile Exchange ADC Telecommunications American National Bank Avery Dennison, Corp. Boeing Co. Chicago Title and Trust Co. Addison Weley Longman American Optical Corp. Avon Products Bonneville International Corp. Chicago Tribune Co. Adobe Systems American Standard AXA Financial Borden Family of Cos. Chiquita Brands International Advanced Micro Devices American States Insurance Baker Hughes Boston Gear Chubb and Sone AEGON USA American Stock Exchange Ball Corp. -

Economic Development Overview

CITY OF BELLEVUE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OVERVIEW Bellevue is a major regional employment center in the Seattle region, with workers traveling to the city from throughout the area. An estimated 148,788 jobs are located in the city. Bellevue is also home to well over 45 corporate headquarters such as: • T-Mobile • PACCAR • Symetra • SAP Concur • Eddie Bauer Bellevue is tied to the global market as businesses are attracted to its highly educated, well trained and diverse workforce. Many of Bellevue’s businesses operate internationally and take advantage of the region’s access to the Asia-Pacific market that provides tremendous opportunities for growth. Bellevue’s global engagement attracts foreign direct investment from around the world. The city is now home to approximately 70 foreign-owned companies from 15 countries. Some of these companies include Aditi Technologies, SAP, Mitsubishi and Samsung. WORKFORCE Bellevue is well known for having a highly educated and innovative workforce. The percentage of Bellevue’s residents, 25 years and older with a Bachelor’s degree or higher, has continued to increase over the decades, rising from 46 percent in 1990 to approximately 61 percent in 2010, one of the highest in the country. Bellevue and the Seattle region are also home to world-class teaching and research universities and colleges that provide the workforce needed for the region’s advanced economy. COMPANIES OPENING OFFICES IN BELLEVUE • REI • SalesForce • BitTitan • Alibaba • AdColony • Huawei The University of Washington is one of the world’s 2000s. Together, they are projected to experience the most preeminent public universities, educating more than 54,000 business opening growth through 2020. -

Why Psychiatry Needs 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine: Achildpsychiatrist’S Perspective

Neurotherapeutics DOI 10.1007/s13311-017-0531-1 REVIEW Why Psychiatry Needs 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine: AChildPsychiatrist’s Perspective Ben Sessa1 # The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract Since the late 1980s the psychoactive drug 3,4- pharmacotherapies and psychotherapies for treating complex methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) has had a well- post-traumatic stress disorder arising from child abuse. known history as the recreationally used drug ecstasy. What is less well known by the public is that MDMA started its life as Key Words MDMA . PTSD . Psychotherapy . Trauma . a therapeutic agent and that in recent years an increasing Psychedelics . addictions amount of clinical research has been undertaken to revisit the drug’s medical potential. MDMA has unique pharmaco- logical properties that translate well to its proposed agent to Introduction: From Child Abuse and Mental assist trauma-focused psychotherapy. Psychological trauma— Disorder to Addictions especially that which arises early in life from child abuse— and 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine underpins many chronic adult mental disorders, including ad- dictions. Several studies of recent years have investigated the I am a child and adolescent psychiatrist, who also works with potential role of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy as a treat- adults with addictions. My adult patients in their 20s, 30s, and ment for post-traumatic stress disorder, with ongoing plans beyond with unremitting depression, anxiety, post-traumatic to see MDMA therapy licensed and approved within the next stress disorder (PTSD), and substance abuse are sadly the 5 years. Issues of safety and controversy frequently surround same type of patients that I also care for as abused children. -

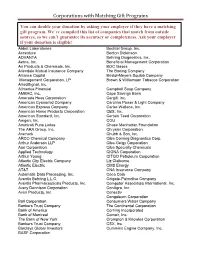

Corporations with Matching Gift Programs

Corporations with Matching Gift Programs You can double your donation by asking your employer if they have a matching gift program. We’ve compiled this list of companies that match from outside sources, so we can’t guarantee its accuracy or completeness. Ask your employer if your donation is eligible! Abbot Laboratories Bechtel Group, Inc. Accenture Becton Dickinson ADVANTA Behring Diagnostics, Inc. Aetna, Inc. Beneficial Management Corporation Air Products & Chemicals, Inc. BOC Gases Allendale Mutual Insurance Company The Boeing Company Alliance Capital Bristol-Meyers Squibb Company Management Corporation, LP Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corporation AlliedSignal, Inc. Allmerica Financial Campbell Soup Company AMBAC, Inc. Cape Savings Bank Amerada Hess Corporation Cargill, Inc. American Cyanamid Company Carolina Power & Light Company American Express Company Carter-Wallace, Inc. American Home Products Corporation CBS, Inc. American Standard, Inc. Certain Teed Corporation Amgen, Inc. CGU Ammirati Puris Lintas Chase Manhattan Foundation The ARA Group, Inc. Chrysler Corporation Aramark Chubb & Son, Inc. ARCO Chemical Company Ciba Corning Diagnostics Corp. Arthur Anderson LLP Ciba-Geigy Corporation Aon Corporation Ciba Specialty Chemicals Applied Technology CIGNA Corporation Arthur Young CITGO Petroleum Corporation Atlantic City Electric Company Liz Claiborne Atlantic Electric CMS Energy AT&T CNA Insurance Company Automatic Data Processing, Inc. Coca Cola Aventis Behring L.L.C. Colgate-Palmolive Company Aventis Pharmaceuticals Products, Inc. Computer Associates International, Inc. Avery Dennison Corporation ConAgra, Inc. Avon Products, Inc. Conectiv Congoleum Corporation Ball Corporation Consumers Water Company Bankers Trust Company The Continental Corporation Bank of America Corning Incorporated Bank of Montreal Comair, Inc. The Bank of New York Crompton & Knowles Corporation Bankers Trust Company CSX, Inc. -

Tragedy on the Descent: the Ascent and Fall of Eddie Bauer

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Chapter 11 Bankruptcy Case Studies College of Law Student Work Spring 2010 Tragedy on the Descent: The Ascent and Fall of Eddie Bauer Austin Fleming Bryan C. Hathorn Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_studlawbankruptcy Part of the Bankruptcy Law Commons Recommended Citation Fleming, Austin and Hathorn, Bryan C., "Tragedy on the Descent: The Ascent and Fall of Eddie Bauer" (2010). Chapter 11 Bankruptcy Case Studies. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_studlawbankruptcy/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law Student Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chapter 11 Bankruptcy Case Studies by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tragedy on the Descent: The Ascent and Fall of Eddie Bauer Austin Fleming1 and Bryan C. Hathorn2 1 B.A. University of Memphis; J.D. University of Tennessee College of Law (expected). 2 B.A. Haverford College; Ph.D. California Institute of Technology; J.D. University of Tennessee College of Law (expected). 1 Contents I. Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 4 II. Corporate History .................................................................................................................... 5 III. The Pre-Petition -

Plaza Level Park Level

SHOPPING The Aveda Store DIRECTORY Bloomingdale’s The Outlet Store Carlens Luxury Optical Carter’s PARK LANE Charming Charlie PARK LEVEL Dick’s Sporting Goods DSW DXL - Casual Male Eddie Bauer PARKING Fans United Forever 21 red Francesca’s 8070 Park Lane HomeGoods J.Crew Mercantile 8080 Park Lane Fusion Academy Koslow’s Furs The Art Institute of Dallas Lane Bryant/Cacique Nordstrom Rack Galleries at Park Lane Grimaldi’s N Old Navy I Love Pizzeria Juice Bar Roma Boots DXL - Casual Male Crisp Zoës Salad Kitchen Sleep Saks Fifth Avenue OFF 5th Co. Number Laser Carlens Away Sleep Number Luxury Optical L'Acqua Nail The Spa Lounge Culinary Bldg. Heights Saint Bernard Which Wich W E The Children’s Place Eddie Bauer Park Dental Loft The Torrid Heights Fans United Hair Fairies ULTA Beauty Bowl & Barrel Vitaliv Francesca’s Unleashed Roma ZYN22 Starbucks Boots S Whole Foods Market J.Crew Mercantile Park ENTERTAINMENT F21 Bowl & Barrel DSW Old Navy Dick’s Sporting Goods DINING Bar Louie The Children’s Place Bowl & Barrel CENTRAL EXPRESSWAY NORTH Crisp Salad Co. Saks Fifth Avenue OFF 5th Bloomingdale's Grimaldi’s Pizzeria The Outlet Store I Love Juice Bar Starbucks Coffee GREENVILLE AVENUE Which Wich Saint Bernard The Aveda Store PLAZA LEVEL Whole Foods Market The Aveda Institute Zoës Kitchen Koslow’s Furs DSW Lane Bryant Cacique Forever Bar Louie Old Navy 21 Red ULTA Beauty HEALTH & BEAUTY Nordstrom Rack AAA Travel The Aveda Store The Derm Lounge HomeGoods Hair Fairies Torrid I Love Juice Bar Studio 6 Fitness L’Acqua Nail Spa Lounge Carter’s The Derm