Theological Progress and Evangelical Commitment Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revelation and Inspiration and the Bible

Revelation and Inspiration and the Bible REVELATION is that act by which God discloses Himself or communicates truth to the mind. We can talk about two kinds of revelation. First there is general revelation - the revelation of God in creation. Psalm 19:1-6 reflects this. Romans 1:19- 20 teaches us that God's attributes, power and divine nature are clearly seen, being understood from what is made. Creation will always wear the "fingerprints" of the Creator. However, Psalm 19:7-14 refers to the the form of revelation, whereby God reveals his will - which we call special revelation - nature cannot reveal moral and spiritual responsibilities - these are communicated verbally. Adam and Eve in the garden had both. Before the fall, they could see clearly God revealed in creation and had his spoken commandments (Gen. 1:28,2:16,17) . They were in personal communication with God. Romans 1:18-25 teaches us that general revelation is sufficient to leave man inexcusable for disbelief, but insufficient for salvation. This is due in part to the fallenness of man, his heart and reason darkened so he cannot understand and he has "suppressed the truth in unrighteousness." Professing wisdom, they became fools, exchanging God for created things- worshipping creation rather than the Creator. (Rom 1:25) As a result they live lives controlled by lusts and passions and darkened minds. (vs. 38) Further there was no need to "build" revelation concerning God's redemption into the creation of a perfect unfallen world. Now that man is fallen, and needs redemption- he needs that special revelation that reveals God's redemptive activity (Rom 10:8-17.) We need special revelation (God's spoken self-disclosure) to correctly perceive Him in the creation and as redeemer and Lord. -

Revelation & Social Reality

Revelation & Social Reality Learning to Translate What Is Written into Reality Paul Lample Palabra Publications Copyright © 2009 by Palabra Publications All rights reserved. Published March 2009. ISBN 978-1-890101-70-1 Palabra Publications 7369 Westport Place West Palm Beach, Florida 33413 U.S.A. 1-561-697-9823 1-561-697-9815 (fax) [email protected] www.palabrapublications.com Cover photograph: Ryan Lash O thou who longest for spiritual attributes, goodly deeds, and truthful and beneficial words! The outcome of these things is an upraised heaven, an outspread earth, rising suns, gleaming moons, scintillating stars, crystal fountains, flowing rivers, subtle atmospheres, sublime palaces, lofty trees, heavenly fruits, rich harvests, warbling birds, crimson leaves, and perfumed blossoms. Thus I say: “Have mercy, have mercy O my Lord, the All-Merciful, upon my blameworthy attributes, my wicked deeds, my unseemly acts, and my deceitful and injurious words!” For the outcome of these is realized in the contingent realm as hell and hellfire, and the infernal and fetid trees, as utter malevolence, loathsome things, sicknesses, misery, pollution, and war and destruction.1 —BAHÁ’U’LLÁH It is clear and evident, therefore, that the first bestowal of God is the Word, and its discoverer and recipient is the power of understanding. This Word is the foremost instructor in the school of existence and the revealer of Him Who is the Almighty. All that is seen is visible only through the light of its wisdom. All that is manifest is but a token -

The New Perspective on Paul: Its Basic Tenets, History, and Presuppositions

TMSJ 16/2 (Fall 2005) 189-243 THE NEW PERSPECTIVE ON PAUL: ITS BASIC TENETS, HISTORY, AND PRESUPPOSITIONS F. David Farnell Associate Professor of New Testament Recent decades have witnessed a change in views of Pauline theology. A growing number of evangelicals have endorsed a view called the New Perspective on Paul (NPP) which significantly departs from the Reformation emphasis on justification by faith alone. The NPP has followed in the path of historical criticism’s rejection of an orthodox view of biblical inspiration, and has adopted an existential view of biblical interpretation. The best-known spokesmen for the NPP are E. P. Sanders, James D. G. Dunn, and N. T. Wright. With only slight differences in their defenses of the NPP, all three have adopted “covenantal nomism,” which essentially gives a role in salvation to works of the law of Moses. A survey of historical elements leading up to the NPP isolates several influences: Jewish opposition to the Jesus of the Gospels and Pauline literature, Luther’s alleged antisemitism, and historical-criticism. The NPP is not actually new; it is simply a simultaneous convergence of a number of old aberrations in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. * * * * * When discussing the rise of the New Perspective on Paul (NPP), few theologians carefully scrutinize its historical and presuppositional antecedents. Many treat it merely as a 20th-century phenomenon; something that is relatively “new” arising within the last thirty or forty years. They erroneously isolate it from its long history of development. The NPP, however, is not new but is the revival of an old ideology that has been around for the many centuries of church history: the revival of works as efficacious for salvation. -

'Solved by Sacrifice' : Austin Farrer, Fideism, and The

‘SOLVED BY SACRIFICE’ : AUSTIN FARRER, FIDEISM, AND THE EVIDENCE OF FAITH Robert Carroll MacSwain A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St. Andrews 2010 Full metadata for this item is available in the St Andrews Digital Research Repository at: https://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/920 This item is protected by original copyright ‘SOLVED BY SACRIFICE’: Austin Farrer, Fideism, and the Evidence of Faith Robert Carroll MacSwain A thesis submitted to the School of Divinity of the University of St Andrews in candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The saints confute the logicians, but they do not confute them by logic but by sanctity. They do not prove the real connection between the religious symbols and the everyday realities by logical demonstration, but by life. Solvitur ambulando, said someone about Zeno’s paradox, which proves the impossibility of physical motion. It is solved by walking. Solvitur immolando, says the saint, about the paradox of the logicians. It is solved by sacrifice. —Austin Farrer v ABSTRACT 1. A perennial (if controversial) concern in both theology and philosophy of religion is whether religious belief is ‘reasonable’. Austin Farrer (1904-1968) is widely thought to affirm a positive answer to this concern. Chapter One surveys three interpretations of Farrer on ‘the believer’s reasons’ and thus sets the stage for our investigation into the development of his religious epistemology. 2. The disputed question of whether Farrer became ‘a sort of fideist’ is complicated by the many definitions of fideism. -

An Introduction to Christian Apologetics (1948)

Christianity has never lacked articulate defenders, but many people today have forgotten their own heritage. Rob Bowman’s book offers readers of all backgrounds an easy point of entry to this deep and vibrant literature. I wish every pastor knew at least this much about the faithful thinkers of past generations! Timothy McGrew Professor of Philosophy, Western Michigan University Director, Library of Historical Apologetics This is a fantastic little book, written by the perfect person to write it. Bowman’s new Faith Thinkers offers a helpful “Who’s Who” of the great Christian apologists of history and is an excellent resource for students of apologetics! James K. Dew President, New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary Finally—an accessible introduction to many of history’s most in- fluential defenders of the Christian faith and their legacy. Always interesting (and often surprising), Robert Bowman’s Faith Thinkers will give a new generation of readers a greater appreciation for the remarkable men who laid the groundwork for today’s apologetics renaissance. Highly recommended. Paul Carden Executive Director, The Centers for Apologetics Research (CFAR) Faith Thinkers 30 Christian Apologists You Should Know Robert M. Bowman Jr. President, Faith Thinkers Inc. CONTENTS Introduction: Two Thousand Years of Faith Thinkers . 9 Part One: Before the Twentieth Century 1. Luke Acts of the Apostles (c. AD 61) . 15 2. Justin Martyr First Apology (157) . .19 3. Origen Against Celsus (248) . .22 4. Augustine The City of God (426) . 25 5. Anselm of Canterbury Proslogion (1078) . .29 6. Thomas Aquinas Summa Contra Gentiles (1263) . .33 7. John Calvin Institutes of the Christian Religion (1536) . -

Progressive Revelation

PROGRESSIVE REVELATION THE Protevangelium, God's word of salvation to fallen man in Paradise, is the beginning of the special revelation contained in the Bible. Only in Eden has general revelation been adequate to the needs of man. Man having fallen, " God breaks His way in a round-about fashion into man's darkened heart to reveal there His redemptive love. By slow steps and gradual stages He at once works out His saving purpose and moulds the world for its reception, choosing a people for Himself and training it through long and weary ages, until at last when the fulness of time has come, He bares His arm and sends out the proclamation of His great salvation to all the earth " (Warfield). The whole history of salvation is one coming of God to His people, one speech of grace to man. It is an historical revelation given first through patriarchs and prophets and ultimately in the Son-a revelation essentially different from the general manifestation of God, e.g. in the works of His hands or in the rational nature of man, because it is redemptive in purpose and soteriological in character. This "word" of God is a revelation of grace and salvation. Under the old covenant men served as the medium through which this word was sounded, until finally the whole revelation is summed up in the one moment of incarnation, when the Word Himself became flesh. It seems quite evident, therefore, that God chose to give the revelation of His grace only progressively, or in other words through the process of an historical development. -

The Authority of Scripture According to Scripture* JAMES D

The Authority of Scripture According to Scripture* JAMES D. G. DUNN I The issue 1) What is the issue concerning Scripture that seems to be dividing and confusing evangelicals today? It is not, I believe, the question of inspiration as such: of whether and how the Bible was inspired. No evangelical that I know of would wish to deny that the biblical writers were inspired by God in what they wrote, or to dispute the basic assertions of 2 Timothy 3:16 and 2 Peter 1:21. Nor is it, I believe, the question of authority as such: of whether the Bible is authoritative for Christians. All evangelicals are united in affirming that the Bible is the Word of God unto salvation, the constitutional authority for the church's faith and life. Where evangelicals begin to disagree is over the implications and corollaries of these basic affirmations of the Bible's inspiration and authority. When we begin to unpack these basic affirmations, how much more is involved in them? How much more is necessarily involved in them? The disagreement, it is worth noting right away, depends partly on theological considerations (what is the theological logic of affirming the inspiration of Scripture?), and partly on apologetic and pastoral concerns (what cannot we yield concerning the Bible's authority without endangering the whole faith, centre as well as circumference?). In order to maintain these affirmations (inspiration and authority) with consistency of faith and logic, in order to safeguard these affirmations from being undermined or weakened-what more precisely must -

The Significance of Christ's Resurrection." Christiancourier.Com

The Significance of Christ’s Resurrection By Wayne Jackson Each spring, millions of people around the world acknowledge, in some fashion or another, that Jesus Christ was raised from the dead some twenty centuries ago. Modern society calls it “Easter.” The origin of this term is uncertain, though it is commonly thought to derive from Eastre, the name of a Teutonic spring goddess. The term “Easter,” in the King James Version of the Bible (Acts 12:4), is a mistranslation. The Greek word is pascha, correctly rendered “Passover” in later translations. In fact, though pascha is found twenty-nine times in the Greek New Testament, it is only rendered “Easter” once, even in the KJV. Christians are not authorized to celebrate Easter as a special annual event acknowledging the resurrection of Christ. Faithful children of God reflect upon the Savior’s resurrection every Sunday (the resurrection day – cf. John 20:1ff) as they gather to worship God in the regular assembly of the church (cf. Acts 20:7; 1 Corinthians 16:2). We ought to be glad, however, that multitudes—usually caught up in pursuits wholly materialistic—will take at least some time for reflection upon the event of the Savior’s resurrection. It is entirely appropriate that Christians take advantage of this circumstance; we should be both willing and able to explain to our friends—at least those who have some reverence for Christianity—the significance of the Lord’s resurrection. The resurrection of Jesus from the dead is the foundation of the Christian system (cf. 1 Corinthians 15:14ff). -

Question 38 - Can General Revelation in and by Itself Bring Someone to a Saving Knowledge of Jesus Christ?

Liberty University Scholars Crossing 101 Most Asked Questions 101 Most Asked Questions About the Bible 1-2019 Question 38 - Can General Revelation in and by itself bring someone to a saving knowledge of Jesus Christ? Harold Willmington Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/questions_101 Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Willmington, Harold, "Question 38 - Can General Revelation in and by itself bring someone to a saving knowledge of Jesus Christ?" (2019). 101 Most Asked Questions. 12. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/questions_101/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the 101 Most Asked Questions About the Bible at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in 101 Most Asked Questions by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 101 MOST ASKED QUESTIONS ABOUT THE BIBLE 38. Can General Revelation in and by itself bring someone to a saving knowledge of Jesus Christ? Theologian Millard Erickson responds as follows: “But what of the judgment of man, spoken of by Paul in Romans 1 and 2? If it is just for God to condemn man, and if man can become guilty without having known God’s special revelation, does that mean that man without special revelation can do what will enable him to avoid the condemnation of God? In Rom. 2:14 Paul says: ‘When Gentiles who have not the law, do by nature what the law requires, they are a law to themselves, even though they do not have the law.’ Is Paul suggesting that they could have fulfilled the requirements of the law? “What if someone then were to throw himself upon the mercy of God, not knowing upon what basis that mercy was provided? Would he not in a sense be in the same situation as the Old Testament believers? The doctrine of Christ and his atoning work had not been fully revealed to these people. -

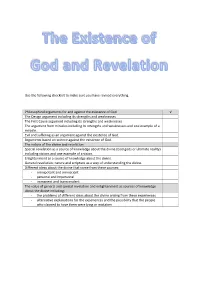

GCSE Revision the Existence of God and Revelation Revision Guide

Use the following checklist to make sure you have revised everything. Philosophical arguments for and against the existence of God √ The Design argument including its strengths and weaknesses. The First Cause argument including its strengths and weaknesses The argument from miracles including its strengths and weaknesses and one example of a miracle. Evil and suffering as an argument against the existence of God. Arguments based on science against the existence of God. The nature of the divine and revelation Special revelation as a source of knowledge about the divine (God gods or ultimate reality) including visions and one example of a vision. Enlightenment as a source of knowledge about the divine. General revelation: nature and scripture as a way of understanding the divine. Different ideas about the divine that come from these sources: - omnipotent and omniscient - personal and impersonal - immanent and transcendent. The value of general and special revelation and enlightenment as sources of knowledge about the divine including: - the problems of different ideas about the divine arising from these experiences - alternative explanations for the experiences and the possibility that the people who claimed to have them were lying or mistaken Agnostic: Belief that there is insufficient evidence to say whether God exists or not. All-compassionate: Characteristic of God; all-loving, omnibenevolent. All-merciful: Characteristic of God; always forgiving and never vindictive. Atheism: Belief that there is no God. Benevolent: Characteristic of God; all-loving. Conscience: Sense of right and wrong; seen as the voice of God within our mind by many religious believers. Design argument: Also known as teleological argument. -

Theology and Philosophy of Religion

Theology and Philosophy of Religion INTRODUCTION Trends and movements are mercurial things, difficult to identify over any significant period of time. In the areas of both Christian Doctrine and Philosophy of Religion, there is a multiplicationof volumes which by its very massiveness creates a problem for the purchaser of books for a ministerial library. What is needed, in many cases at least, is a guide to selectivity. This in turn is made more difficult in the case of recent publi cations by the fact that the disciplines are subject to what may be called a "Guru mentality" which seeks for some one prominent teacher, and then adopts him as a personal mentor. This "Guru mentality" expresses itself most prominently in our time in one of two directions. Either the leadership of Paul Tillich is accepted, usually without too much critical analysis in advance, and then certain catch-phrases of the famous theologian become determinative for theological dis cussion, or else the methodology of Rudolf Bultmann is seized as offering a way out of modern man's theological illiteracy, Some are and theological discussion is tailored to fit. , however, beginningtoquestionwhether either of these men is of sufficient permanent significance to warrant adoption as one to be followed, whithersoever he may go. Thus, there has been, within a decade, somewhat of a shift from the faddism of a movement, to a faddism of men. Ten years ago, Existentialism was a fad to the extent that many thinkers believed that he who failed to read at least something from So ren Kierkegaard or Martin Heidegger was a theological boor. -

The Problem of Revelation

THE PROBLEM OF REVELATION Regarding the basic meaning of the term "revelation" there is a fair degree of consensus in our time. The term may be defined either phe- nomenologically or theologically. Phenomenologically, it signifies a sud- den or unexpected disclosure of a deeply meaningful truth or reality. Revelation usually connotes that the new awareness or knowledge comes upon one as a gift, that it answers a real need, and that it effects a wonderful transformation in the recipient. Theologically, revelation signifies an action of God by which he makes known himself or something he intends to manifest. The theo- logical notion of revelation presupposes, or at least implies, that God exists and has dealings with the world. Divine revelation, according to Christian theologians, is a gift; it answers a real need—delivery from darkness and death—and makes a profound difference, inasmuch as it "justifies" or "saves" those who would otherwise perish. Christians believe that God's revealing action undergirds the faith of ancient Israel and that of the Christian Church. The Bible, which expresses this histor- ical faith, is accordingly viewed as a primary document of revelation. Notwithstanding these basic agreements there is no consensus among Christian or Catholic theologians as to the forms in which revela- tion comes, where it is principally found, or how it is related to faith. In the present paper I shall seek to classify and evaluate some of the most prominent modern theories.1 My own concern is with the logical schematization of positions, but in order to give concreteness and actuality to the analysis I shall take the risk of naming some authors as representatives of the various points of view.