Help Urban Trees Survive a Drought

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Urban Lifestyle

UL introduces the Supplier Forum, a new and exciting way to learn about trends from industry experts. Urban Lifestyle Dr. Fred Zülli, Ph.D. Dr. Stefan Bänziger, Ph.D. Abbie Piero Managing Director Head of R&D and Engineering Forum Moderator Mibelle AG Biochemistry, Switzerland Lipoid Kosmetik UL Prospector Urban Lifestyle In 2030 more than 60% of total population will live in big cities Urbanization will change lifestyle New demand for cosmetics with increase in wellbeing © Mibelle Biochemistry, Switzerland 2020 Cosmetic Active Concepts 1. Hectic, stressed lifestyle → fighting skin irritations induced by glucocorticoids 2. Exhaustive lifestyle → boosting energy levels 3. Lack of sleep → avoiding skin aging by improved protein folding 4. Digital dependence → protection against blue light 5. Feel good → look good with phyto-endorphins 6. Health & eco-consciousness → supplementing skin care for a vegan lifestyle © Mibelle Biochemistry, Switzerland 2020 1. Hectic, Stressed Lifestyle and Skin © Mibelle Biochemistry, Switzerland 2020 What is Stress? Acute stress • Body's reaction to demanding or dangerous situations („fight or flight“) • Short term • Acute stress is thrilling and exciting and body usually recovers quickly • Adrenaline fight or flight © Mibelle Biochemistry, Switzerland 2020 What is Stress? Chronic stress • Based on stress factors that impact over a longer period • Always bad and has negative effects on the body and the skin • Glucocortioides (Cortisol) © Mibelle Biochemistry, Switzerland 2020 Sources of Psychological Stress -

Abacca Mosaic Virus

Annex Decree of Ministry of Agriculture Number : 51/Permentan/KR.010/9/2015 date : 23 September 2015 Plant Quarantine Pest List A. Plant Quarantine Pest List (KATEGORY A1) I. SERANGGA (INSECTS) NAMA ILMIAH/ SINONIM/ KLASIFIKASI/ NAMA MEDIA DAERAH SEBAR/ UMUM/ GOLONGA INANG/ No PEMBAWA/ GEOGRAPHICAL SCIENTIFIC NAME/ N/ GROUP HOST PATHWAY DISTRIBUTION SYNONIM/ TAXON/ COMMON NAME 1. Acraea acerata Hew.; II Convolvulus arvensis, Ipomoea leaf, stem Africa: Angola, Benin, Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae; aquatica, Ipomoea triloba, Botswana, Burundi, sweet potato butterfly Merremiae bracteata, Cameroon, Congo, DR Congo, Merremia pacifica,Merremia Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, peltata, Merremia umbellata, Kenya, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Ipomoea batatas (ubi jalar, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, sweet potato) Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo. Uganda, Zambia 2. Ac rocinus longimanus II Artocarpus, Artocarpus stem, America: Barbados, Honduras, Linnaeus; Coleoptera: integra, Moraceae, branches, Guyana, Trinidad,Costa Rica, Cerambycidae; Herlequin Broussonetia kazinoki, Ficus litter Mexico, Brazil beetle, jack-tree borer elastica 3. Aetherastis circulata II Hevea brasiliensis (karet, stem, leaf, Asia: India Meyrick; Lepidoptera: rubber tree) seedling Yponomeutidae; bark feeding caterpillar 1 4. Agrilus mali Matsumura; II Malus domestica (apel, apple) buds, stem, Asia: China, Korea DPR (North Coleoptera: Buprestidae; seedling, Korea), Republic of Korea apple borer, apple rhizome (South Korea) buprestid Europe: Russia 5. Agrilus planipennis II Fraxinus americana, -

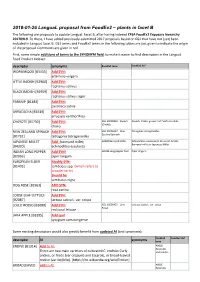

2018-01-26 Langual Proposal from Foodex2 – Plants in Facet B

2018-01-26 LanguaL proposal from FoodEx2 – plants in facet B The following are proposals to update LanguaL Facet B, after having indexed EFSA FoodEx2 Exposure hierarchy 20170919. To these, I have added previously-submitted 2017 proposals based on GS1 that have not (yet) been included in LanguaL facet B. GS1 terms and FoodEx2 terms in the following tables are just given to indicate the origin of the proposal. Comments are given in red. First, some simple additions of terms to the SYNONYM field, to make it easier to find descriptors in the LanguaL Food Product Indexer: descriptor synonyms FoodEx2 term FoodEx2 def WORMWOOD [B3433] Add SYN: artemisia vulgaris LITTLE RADISH [B2960] Add SYN: raphanus sativus BLACK RADISH [B2959] Add SYN: raphanus sativus niger PARSNIP [B1483] Add SYN: pastinaca sativa ARRACACHA [B3439] Add SYN: arracacia xanthorrhiza CHAYOTE [B1730] Add SYN: GS1 10006356 - Squash Squash, Choko, grown from Sechium edule (Choko) choko NEW ZEALAND SPINACH Add SYN: GS1 10006427 - New- Tetragonia tetragonoides Zealand Spinach [B1732] tetragonia tetragonoides JAPANESE MILLET Add : barnyard millet; A000Z Barnyard millet Echinochloa esculenta (A. Braun) H. Scholz, Barnyard millet or Japanese Millet. [B4320] echinochloa esculenta INDIAN LONG PEPPER Add SYN! A019B Long pepper fruit Piper longum [B2956] piper longum EUROPEAN ELDER Modify SYN: [B1403] sambucus spp. (which refers to broader term) Should be sambucus nigra DOG ROSE [B2961] ADD SYN: rosa canina LOOSE LEAF LETTUCE Add SYN: [B2087] lactusa sativa L. var. crispa LOLLO ROSSO [B2088] Add SYN: GS1 10006425 - Lollo Lactuca sativa L. var. crispa Rosso red coral lettuce JAVA APPLE [B3395] Add syn! syzygium samarangense Some existing descriptors would also greatly benefit from updated AI (and synonyms): FoodEx2 FoodEx2 def descriptor AI synonyms term ENDIVE [B1314] Add to AI: A00LD Escaroles There are two main varieties of cultivated C. -

'Wild Harvest in Time of New Pests, Diseases and Climate Change'

Wild harvested nuts and berries in times of new pests, diseases and climate change Round 2 Interregional Workshop of the Wild nuts and berries iNet 12-14, June, Palencia, Spain (& fieldtrips) 1. AGENDA ............................................................................................................................ 1 2. iNet THEMES AND KNOWLEDGE GAPS ............................................................................... 4 3. ATTENDEES ....................................................................................................................... 4 4. WORKSHOP ...................................................................................................................... 5 4.1. Presentations ................................................................................................................ 5 4.2. Work group sessions ...................................................................................................... 8 4.3. Field trips ...................................................................................................................... 10 5. CONCLUSIONS ................................................................................................................ 11 References ......................................................................................................................... 12 1. AGENDA The scoping seminar of the Wild nuts and berries iNet put forward priorities themes to focus INCREDIBLE actions. One of the topics highlighted was the “Long-term resource -

Herbs, Spices and Essential Oils

Printed in Austria V.05-91153—March 2006—300 Herbs, spices and essential oils Post-harvest operations in developing countries UNITED NATIONS INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box 300, 1400 Vienna, Austria Telephone: (+43-1) 26026-0, Fax: (+43-1) 26926-69 UNITED NATIONS FOOD AND AGRICULTURE E-mail: [email protected], Internet: http://www.unido.org INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION OF THE ORGANIZATION UNITED NATIONS © UNIDO and FAO 2005 — First published 2005 All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product for educational or other non-commercial purposes are authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of material in this information product for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holders. Applications for such permission should be addressed to: - the Director, Agro-Industries and Sectoral Support Branch, UNIDO, Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box 300, 1400 Vienna, Austria or by e-mail to [email protected] - the Chief, Publishing Management Service, Information Division, FAO, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy or by e-mail to [email protected] The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization or of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

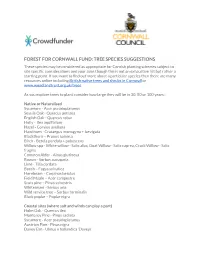

Tree Species Suggestion List

FOREST FOR CORNWALL FUND: TREE SPECIES SUGGESTIONS These species may be considered as appropriate for Cornish planting schemes subject to site specific considerations and your aims though this is not an exhaustive list but rather a starting point. If you want to find out more about a particular species then there are many resources online including British native trees and shrubs in Cornwall or www.woodlandtrust.org.uk/trees As you explore trees to plant consider how large they will be in 30, 50 or 100 years : Native or Naturalised Sycamore - Acer pseudoplatanus Sessile Oak - Quercus petraea English Oak - Quercus robur Holly - Ilex aquifolium Hazel - Corylus avellana Hawthorn - Crataegus monogyna + laevigata Blackthorn – Prunus spinosa Birch - Betula pendula + pubescens Willow spp - White willow - Salix alba, Goat Willow - Salix caprea, Crack Willow - Salix fragilis Common Alder - Alnus glutinosa Rowan - Sorbus aucuparia Lime - Tilia cordata Beech – Fagus sylvatica Hornbeam - Carpinus betulus Field Maple – Acer campestre Scots pine – Pinus sylvestris Whitebeam –Sorbus aria Wild service tree – Sorbus torminalis Black poplar – Poplar nigra Coastal sites (where salt and winds can play a part) Holm Oak - Quercus ilex Monterey Pine - Pinus radiata Sycamore - Acer pseudoplatanus Austrian Pine - Pinus nigra Davey Elm - Ulmus x hollandica ‘Daveyi’ Maritime pine - Pinus pinaster Non-natives for amenity and landscape planting Birch - Betula spp Swamp Cypress - Taxodium distichum Dawn Redwood - Metasequoia glyptostroboides Plane - Platanus occidentalis -

Edible Seeds

List of edible seeds This list of edible seeds includes seeds that are directly 1 Cereals foodstuffs, rather than yielding derived products. See also: Category:Cereals True cereals are the seeds of certain species of grass. Quinoa, a pseudocereal Maize A variety of species can provide edible seeds. Of the six major plant parts, seeds are the dominant source of human calories and protein.[1] The other five major plant parts are roots, stems, leaves, flowers, and fruits. Most ed- ible seeds are angiosperms, but a few are gymnosperms. The most important global seed food source, by weight, is cereals, followed by legumes, and nuts.[2] The list is divided into the following categories: • Cereals (or grains) are grass-like crops that are har- vested for their dry seeds. These seeds are often ground to make flour. Cereals provide almost half of all calories consumed in the world.[3] Botanically, true cereals are members of the Poaceae, the true grass family. A mixture of rices, including brown, white, red indica and wild rice (Zizania species) • Pseudocereals are cereal crops that are not Maize, wheat, and rice account for about half of the grasses. calories consumed by people every year.[3] Grains can be ground into flour for bread, cake, noodles, and other • Legumes including beans and other protein-rich food products. They can also be boiled or steamed, ei- soft seeds. ther whole or ground, and eaten as is. Many cereals are present or past staple foods, providing a large fraction of the calories in the places that they are eaten. -

Identifying Ritual Deposition of Plant Remains: a Case Study of Stone Pine Cones in Roman Britain

Identifying ritual deposition of plant remains: a case study of stone pine cones in Roman Britain Book or Report Section Accepted Version Lodwick, L. (2015) Identifying ritual deposition of plant remains: a case study of stone pine cones in Roman Britain. In: Brindle, T., Allen, M., Durham, E. and Smith, A. (eds.) TRAC 2014: Proceedings of the Twenty-Fourth Annual Theoretical Roman Archaeology Conference. Oxbow, Oxford, pp. 54-69. ISBN 9781785700026 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/54473/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Publisher: Oxbow All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Identifying Ritual Deposition of Plant Remains: a Case Study of Stone Pine Cones in Roman Britain Introduction The identification and theorisation of ritualised deposition in the Roman world has received significant research focus over the last decade (Fulford 2001; Smith 2001). Yet, as within other theory-heavy areas of Roman archaeology (Pitts 2007), plant remains have been poorly integrated into key synthetic works. Analysis has instead focussed on artefactual and zooarchaeological remains (Smith 2001; Morris 2010), with plant remains only briefly alluded to, or discussed largely within specialist archaeobotanical literature (Robinson 2002; Vandorpe and Jacomet 2011). Whilst there is growing evidence for the use of plants in non-funerary classical Roman religion, as well as structured-deposition in shafts and pits, the absence of systematic methodologies and contextual analysis limits the study of ritual plant use in the Roman world. -

Pinus Pinea Pinus Pinea

Pinus pinea Pinus pinea Pinus pinea in Europe: distribution, habitat, usage and threats R. Abad Viñas, G. Caudullo, S. Oliveira, D. de Rigo The stone pine (Pinus pinea L.) is a medium-sized tree with an umbrella-shaped, large and flat crown, scattered around the Mediterranean basin, mainly in coastal areas, and particularly abundant in south Western Europe. It occupies a broad range of climate and soil conditions, although it shows a low genetic variation. It thrives in dry weather, strong direct sunlight and high temperatures, tolerating light-shaded conditions at the early stages of its growth. It prefers acidic, siliceous soils but also tolerates calcareous ones. The most important economic products obtained from these pines are the edible seeds (pine nuts), although they are also used for consolidation of sand dunes in coastal areas, for timber, hunting and grazing activities. This pine species is rarely attacked by pests and diseases, despite some fungi diseases that can cause damages to seedlings and young plantations. In the Mediterranean basin, forest fires constitute the major threat to the stone pine, even though its thick bark and high crown make it less sensitive to fire than other pine species. The stone pine (Pinus pinea L.) is a medium sized evergreen coniferous tree, which grows up to 25-30 m with trunks exceeding Frequency 2 m in diameter. The crown is globose and shrubby in youth, < 25% 25% - 50% umbrella-shaped in mid-age and flat and broad in maturity. The 50% - 75% trunk is often short and with numerous upward angled branches > 75% Chorology with foliage near to the ends. -

Mediterranean Stone Pine for Agroforestry Pine As a Nut Crop and to Analyse Its Potential and Current Challenges

OPTIONS OPTIONS méditerranéennes méditerranéennes Mediterranean Stone Pine SERIES A: Mediterranean Seminars CIHEAM 2013 – Number 105 for Agroforestry Mediterranean Stone Pine Edited by: S. Mutke, M. Piqué, R. Calama for Agroforestry Edited by: S. Mutke, M. Piqué, R. Calama The pine nut, the edible kernel of the Mediterranean stone pine, Pinus pinea, is one of the world’s most expensive nuts. Although well known and planted since antiquity, pine nuts are still collected mainly from natural forests in the Mediterranean countries, and only recently has the crop taken the first steps to domestication as an attractive alternative on rainfed farmland in Mediterranean climate areas, with plantations yielding more pine nuts than the natural forests and contributing to rural development and employment of local communities. The species performs well on poor soils and needs little husbandry, it is affected by few pests or diseases and withstands adverse climatic conditions such as drought and extreme or late frosts. It is light-demanding and hence has potential as a crop in agro forestry systems in Mediterranean climate zones around the world. This publication contains 14 of the contributions presented at the AGROPINE 2011 Meeting, held from 17 to 19 November 2011 in Valladolid (Spain). The Meeting aimed at bringing together the main research groups and potential users in order to gather the current knowledge on Mediterranean stone OPTIONS OPTIONS méditerranéennes Mediterranean Stone Pine for Agroforestry pine as a nut crop and to analyse its potential and current challenges. The presentations and debates méditerranéennes were structured into two scientific sessions dealing with management of stone pine for cone production and on genetic improvement, selection and breeding of this species, and was closed by a round -table discussion on the challenges and opportunities of the pine nut industry and markets. -

Pine Nuts: a Review of Recent Sanitary Conditions and Market Development

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 17 July 2017 doi:10.20944/preprints201707.0041.v1 Peer-reviewed version available at Forests 2017, 8, 367; doi:10.3390/f8100367 Article Pine nuts: a review of recent sanitary conditions and market development Hafiz Umair M. Awan 1 and Davide Pettenella 2,* 1 Department of Forest Science, University of Helsinki, Finland; [email protected], [email protected] 2 Department Land, Environment, Agriculture and Forestry – University of Padova, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-049-827-2741 Abstract: Pine nuts are non-wood forest products (NWFP) with constantly growing market notwithstanding a series of phytosanitary issues and related trade problems. The aim of paper is to review the literature on the relationship between phytosanitary problems and trade development. Production and trade of pine nuts in Mediterranean Europe have been negatively affected by the spreading of Sphaeropsis sapinea (a fungus) associated to an adventive insect Leptoglossus occidentalis (fungal vector), with impacts on forest management activities, production and profitability and thus in value chain organization. Reduced availability of domestic production in markets with growing demand has stimulated the import of pine nuts. China has become a leading exporter of pine nuts, but its export is affected by a symptom associated to the nuts of some pine species: the ‘pine nut syndrome’ (PNS). Most of the studies embraced during the review are associated to PNS occurrence associated to the nuts of Pinus armandii. In the literature review we highlight the need for a comprehensive and interdisciplinary approach to the analysis of the pine nuts value chain organization, where research on food properties and clinical toxicology be connected to breeding and forest management, forest pathology and entomology and trade development studies. -

Pinus Pinea Stone Pine1 Edward F

Fact Sheet ST-472 October 1994 Pinus pinea Stone Pine1 Edward F. Gilman and Dennis G. Watson2 INTRODUCTION Just as its name implies, Umbrella Pine has a broad, somewhat flattened round canopy, and the tree will ultimately reach 80 to 100 feet in height though it is more often seen at 35 to 45 feet tall and wide (Fig. 1). The bright green, stiff, six-inch-long needles are arranged in slightly twisted bundles, and are joined by the heavy, five to six-inch-long cones which remain tightly closed on the tree for three years. The trunk is showy with narrow, foot-long orange plates set off nicely by darker fissures. GENERAL INFORMATION Figure 1. Mature Stone Pine. Scientific name: Pinus pinea Pronunciation: PIE-nus pie-NEE-uh Common name(s): Stone Pine, Italian Stone Pine, DESCRIPTION Umbrella Pine Family: Pinaceae Height: 35 to 60 feet USDA hardiness zones: 7 through 11 (Fig. 2) Spread: 35 to 45 feet Origin: not native to North America Crown uniformity: symmetrical canopy with a Uses: Bonsai; fruit tree; large parking lot islands (> regular (or smooth) outline, and individuals have more 200 square feet in size); wide tree lawns (>6 feet or less identical crown forms wide); medium-sized parking lot islands (100-200 Crown shape: round; vase shape square feet in size); medium-sized tree lawns (4-6 feet Crown density: dense wide); recommended for buffer strips around parking Growth rate: medium lots or for median strip plantings in the highway; Texture: fine screen; shade tree; narrow tree lawns (3-4 feet wide); specimen; sidewalk cutout (tree pit); no proven urban Foliage tolerance Availability: somewhat available, may have to go out Leaf arrangement: alternate; spiral (Fig.