Not Black Enough: Singing Group, the Five Heartbeats, the Cost of a Static View of What It Means to Be from the 1960S to the 1990S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Melissa Jefferson V. Justin Raisen Et

Case 2:19-cv-09107-DMG-MAA Document 79 Filed 04/27/21 Page 1 of 7 Page ID #:489 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA CIVIL MINUTES—GENERAL Case No. CV 19-9107-DMG (MAAx) Date April 27, 2021 Title Melissa Jefferson v. Justin Raisen, et al. Page 1 of 7 Present: The Honorable DOLLY M. GEE, UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE KANE TIEN NOT REPORTED Deputy Clerk Court Reporter Attorneys Present for Plaintiff(s) Attorneys Present for Defendant(s) None Present None Present Proceedings: IN CHAMBERS—ORDER RE PLAINTIFF/COUNTER-DEFENDANT’S MOTION TO DISMISS DEFENDANTS/COUNTERCLAIMANTS’ FIRST AMENDED COUNTERCLAIM [60] On August 14, 2020, the Court granted Plaintiff Melissa Jefferson’s (known professionally as Lizzo) motion to dismiss Defendants Justin Raisen, Jeremiah Raisen, Yves Rothman, and Heavy Duty Music Publishing’s Counterclaims for failure to state a claim, with leave to amend. [Doc. # 57 (“first MTD Order” or “MTD1 Order”).] On September 3, 2020, Counterclaimants filed their First Amended Answer (“FAA”), which contains counterclaims for: (1) a judicial declaration that they are joint authors and co-owners of Truth Hurts; (2) an accounting of revenues from the use of Healthy in Truth Hurts; (3) “further relief” under 28 U.S.C. § 2202; (4) an accounting of revenues from Truth Hurts enjoyed by all Counter-defendants, or by Lizzo and Jesse St. John Geller (“St. John”); and (5) a constructive trust. [Doc. # 58.] On September 24, 2020, Lizzo filed a second motion to dismiss (“MTD”) the first, third, fourth, and fifth amended counterclaims. [Doc. # 60.] The motion has since been fully briefed. -

Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2019 Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century Saesha Senger University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2020.011 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Senger, Saesha, "Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 150. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/150 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

September 1995

Features CARL ALLEN Supreme sideman? Prolific producer? Marketing maven? Whether backing greats like Freddie Hubbard and Jackie McLean with unstoppable imagination, or writing, performing, and producing his own eclectic music, or tackling the business side of music, Carl Allen refuses to be tied down. • Ken Micallef JON "FISH" FISHMAN Getting a handle on the slippery style of Phish may be an exercise in futility, but that hasn't kept millions of fans across the country from being hooked. Drummer Jon Fishman navigates the band's unpre- dictable musical waters by blending ancient drum- ming wisdom with unique and personal exercises. • William F. Miller ALVINO BENNETT Have groove, will travel...a lot. LTD, Kenny Loggins, Stevie Wonder, Chaka Khan, Sheena Easton, Bryan Ferry—these are but a few of the artists who have gladly exploited Alvino Bennett's rock-solid feel. • Robyn Flans LOSING YOUR GIG AND BOUNCING BACK We drummers generally avoid the topic of being fired, but maybe hiding from the ax conceals its potentially positive aspects. Discover how the former drummers of Pearl Jam, Slayer, Counting Crows, and others transcended the pain and found freedom in a pink slip. • Matt Peiken Volume 19, Number 8 Cover photo by Ebet Roberts Columns EDUCATION NEWS EQUIPMENT 100 ROCK 'N' 10 UPDATE 24 NEW AND JAZZ CLINIC Terry Bozzio, the Captain NOTABLE Rhythmic Transposition & Tenille's Kevin Winard, BY PAUL DELONG Bob Gatzen, Krupa tribute 30 PRODUCT drummer Jack Platt, CLOSE-UP plus News 102 LATIN Starclassic Drumkit SYMPOSIUM 144 INDUSTRY BY RICK -

Helena Mace Song List 2010S Adam Lambert – Mad World Adele – Don't You Remember Adele – Hiding My Heart Away Adele

Helena Mace Song List 2010s Adam Lambert – Mad World Adele – Don’t You Remember Adele – Hiding My Heart Away Adele – One And Only Adele – Set Fire To The Rain Adele- Skyfall Adele – Someone Like You Birdy – Skinny Love Bradley Cooper and Lady Gaga - Shallow Bruno Mars – Marry You Bruno Mars – Just The Way You Are Caro Emerald – That Man Charlene Soraia – Wherever You Will Go Christina Perri – Jar Of Hearts David Guetta – Titanium - acoustic version The Chicks – Travelling Soldier Emeli Sande – Next To Me Emeli Sande – Read All About It Part 3 Ella Henderson – Ghost Ella Henderson - Yours Gabrielle Aplin – The Power Of Love Idina Menzel - Let It Go Imelda May – Big Bad Handsome Man Imelda May – Tainted Love James Blunt – Goodbye My Lover John Legend – All Of Me Katy Perry – Firework Lady Gaga – Born This Way – acoustic version Lady Gaga – Edge of Glory – acoustic version Lily Allen – Somewhere Only We Know Paloma Faith – Never Tear Us Apart Paloma Faith – Upside Down Pink - Try Rihanna – Only Girl In The World Sam Smith – Stay With Me Sia – California Dreamin’ (Mamas and Papas) 2000s Alicia Keys – Empire State Of Mind Alexandra Burke - Hallelujah Adele – Make You Feel My Love Amy Winehouse – Love Is A Losing Game Amy Winehouse – Valerie Amy Winehouse – Will You Love Me Tomorrow Amy Winehouse – Back To Black Amy Winehouse – You Know I’m No Good Coldplay – Fix You Coldplay - Yellow Daughtry/Gaga – Poker Face Diana Krall – Just The Way You Are Diana Krall – Fly Me To The Moon Diana Krall – Cry Me A River DJ Sammy – Heaven – slow version Duffy -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

Grammy Museum® Announces New Program Series Titled Spotlight Saturdays

GRAMMY MUSEUM® ANNOUNCES NEW PROGRAM SERIES TITLED SPOTLIGHT SATURDAYS REPUBLIC RECORDS WILL BE THE FIRST LABEL TO TAKE OVER THE SERIES STARTING WITH ARTISTS BENEE, DUCKWRTH, CONAN GRAY, KIANA LEDÉ, AND JEREMY ZUCKER FOR MONTH OF AUGUST WHAT: GRAMMY Museum® announces a new program series titled Spotlight Saturdays featuring up- and-coming artists every Saturday. Each month will be in collaboration with a label, with the first takeover by Republic Records. Spotlight Saturdays is part of the Museum's Public Programs digital series, which features intimate sit-down interviews and performances via digital conferencing. More August programming to be announced soon. WHO: Spotlight Saturdays schedule below featuring August takeover by Republic Records. 8/1 — Kiana Ledé 8/8 — BENEE 8/15 — Conan Gray 8/22 — Duckwrth 8/29 — Jeremy Zucker WHEN: Every Saturday starting Aug. 1. WHERE: All content is released at the Digital Museum: www.grammymuseum.org ABOUT THE GRAMMY MUSEUM The GRAMMY Museum is a nonprofit organization dedicated to cultivating a greater understanding of the history and significance of music through exhibits, education, grants, preservation initiatives, and public programming. Paying tribute to our collective musical heritage, the Museum explores and celebrates all aspects of the art form — from the technology of the recording process to the legends who've made lasting marks on our cultural identity. For more information, visit www.grammymuseum.org, "like" the GRAMMY Museum on Facebook, and follow @GRAMMYMuseum on Twitter and Instagram. ▪ GRAMMY Museum® Announces New Program Series Titled Spotlight Saturdays | Page 1 of 3 BENEE From Auckland, New Zealand, breakthrough pop star Stella Bennett, aka BENEE, remains unfazed, unchanged and almost impervious to the cataclysmic success coming her way since releasing her debut EP, FIRE ON MARZZ, last summer. -

2020 C'nergy Band Song List

Song List Song Title Artist 1999 Prince 6:A.M. J Balvin 24k Magic Bruno Mars 70's Medley/ I Will Survive Gloria 70's Medley/Bad Girls Donna Summers 70's Medley/Celebration Kool And The Gang 70's Medley/Give It To Me Baby Rick James A A Song For You Michael Bublé A Thousands Years Christina Perri Ft Steve Kazee Adventures Of Lifetime Coldplay Ain't It Fun Paramore Ain't No Mountain High Enough Michael McDonald (Version) Ain't Nobody Chaka Khan Ain't Too Proud To Beg The Temptations All About That Bass Meghan Trainor All Night Long Lionel Richie All Of Me John Legend American Boy Estelle and Kanye Applause Lady Gaga Ascension Maxwell At Last Ella Fitzgerald Attention Charlie Puth B Banana Pancakes Jack Johnson Best Part Daniel Caesar (Feat. H.E.R) Bettet Together Jack Johnson Beyond Leon Bridges Black Or White Michael Jackson Blurred Lines Robin Thicke Boogie Oogie Oogie Taste Of Honey Break Free Ariana Grande Brick House The Commodores Brown Eyed Girl Van Morisson Butterfly Kisses Bob Carisle C Cake By The Ocean DNCE California Gurl Katie Perry Call Me Maybe Carly Rae Jespen Can't Feel My Face The Weekend Can't Help Falling In Love Haley Reinhart Version Can't Hold Us (ft. Ray Dalton) Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Can't Stop The Feeling Justin Timberlake Can't Get Enough of You Love Babe Barry White Coming Home Leon Bridges Con Calma Daddy Yankee Closer (feat. Halsey) The Chainsmokers Chicken Fried Zac Brown Band Cool Kids Echosmith Could You Be Loved Bob Marley Counting Stars One Republic Country Girl Shake It For Me Girl Luke Bryan Crazy in Love Beyoncé Crazy Love Van Morisson D Daddy's Angel T Carter Music Dancing In The Street Martha Reeves And The Vandellas Dancing Queen ABBA Danza Kuduro Don Omar Dark Horse Katy Perry Despasito Luis Fonsi Feat. -

Afrofuturism: the World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture

AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISM Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 1 5/22/13 3:53 PM Copyright © 2013 by Ytasha L. Womack All rights reserved First edition Published by Lawrence Hill Books, an imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Womack, Ytasha. Afrofuturism : the world of black sci-fi and fantasy culture / Ytasha L. Womack. — First edition. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 (trade paper) 1. Science fiction—Social aspects. 2. African Americans—Race identity. 3. Science fiction films—Influence. 4. Futurologists. 5. African diaspora— Social conditions. I. Title. PN3433.5.W66 2013 809.3’8762093529—dc23 2013025755 Cover art and design: “Ioe Ostara” by John Jennings Cover layout: Jonathan Hahn Interior design: PerfecType, Nashville, TN Interior art: John Jennings and James Marshall (p. 187) Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 I dedicate this book to Dr. Johnnie Colemon, the first Afrofuturist to inspire my journey. I dedicate this book to the legions of thinkers and futurists who envision a loving world. CONTENTS Acknowledgments .................................................................. ix Introduction ............................................................................ 1 1 Evolution of a Space Cadet ................................................ 3 2 A Human Fairy Tale Named Black .................................. -

MALIK H. SAYEED Director of Photography

MALIK H. SAYEED Director of Photography official website COMMERCIALS (partial list) Verizon, Workday ft. Naomi Osaka, IBM, M&Ms, *Beats by Dre, Absolut, Chase, Kellogg’s, Google, Ellen Beauty, Instagram, AT&T, Apple, Adidas, Gap, Old Navy, Bumble, P&G, eBay, Amazon Prime, **Netflix “A Great Day in Hollywood”, Nivea, Spectrum, YouTube, Checkers, Lexus, Dobel, Comcast XFinity, Captain Morgan, ***Nike, Marriott, Chevrolet, Sky Vodka, Cadillac, UNCF, Union Bank, 02, Juicy Couture, Tacori Jewelry, Samsung, Asahi Beer, Duracell, Weight Watchers, Gillette, Timberland, Uniqlo, Lee Jeans, Abreva, GMC, Grey Goose, EA Sports, Kia, Harley Davidson, Gatorade, Burlington, Sunsilk, Versus, Kose, Escada, Mennen, Dolce & Gabbana, Citizen Watches, Aruba Tourism, Texas Instruments, Sunlight, Cover Girl, Clairol, Coppertone, GMC, Reebok, Dockers, Dasani, Smirnoff Ice, Big Red, Budweiser, Nintendo, Jenny Craig, Wild Turkey, Tommy Hilfiger, Fuji, Almay, Anti-Smoking PSA, Sony, Canon, Levi’s, Jaguar, Pepsi, Sears, Coke, Avon, American Express, Snapple, Polaroid, Oxford Insurance, Liberty Mutual, ESPN, Yamaha, Nissan, Miller Lite, Pantene, LG *2021 Emmy Awards Nominee – Outstanding Commercial – Beats by Dre “You Love Me” **2019 Emmy Awards Nominee – Outstanding Commercial ***2017 D&AD Professional Awards Winner – Cinematography for Film Advertising – Nike “Equality” MUSIC VIDEOS (partial list) Arianna Grande, Miley Cyrus & Lana Del Rey, Kanye West feat. Nicki Minaj & Ty Dolla $ign, N.E.R.D. & Rihanna, Jay Z, Charli XCX, Damian Marley, *Beyoncé, Kanye West, Nate Ruess, Kendrick Lamar, Sia, Nicole Scherzinger, Arcade Fire, Bruno Mars, The Weekend, Selena Gomez, **Lana Del Rey, Mariah Carey, Nicki Minaj, Drake, Ciara, Usher, Rihanna, Will I Am, Ne-Yo, LL Cool J, Black Eyed Peas, Pharrell, Robin Thicke, Ricky Martin, Lauryn Hill, Nas, Ziggy Marley, Youssou N’Dour, Jennifer Lopez, Michael Jackson, Mary J. -

Beyoncé, the African Diaspora, and the Baptism of 'Black Is King'

NBA PLAYOFF ODDS NFL MLB FANTASY MORE MOVIES MUSIC POP CULTURE Glory B: Beyoncé, the African Diaspora, and the Baptism of ‘Black Is King’ On her new Disney+ visual album, Beyoncé reinforces the ancestral lineage of Black people as divine beings, connecting the experience of a Black woman from the South to shores of Africa By Taylor Crumpton Aug 4, 2020, 6:30am EDT SHARE Parkwood Entertainment/Ringer illustration On July 31 at midnight, time stood still. Only Beyoncé Giselle Knowles-Carter’s creation of a Black planet could make the world forget about a global pandemic. For a moment, she lifted the veil of white supremacist thought that has dehumanized the African Diaspora. Black Is King, her new visual album released on Disney+ on Friday, reinforces the ancestral lineage of Black people as divine beings, born from the natural and spiritual forces of the universe. In the film, Beyoncé plays an omnipresent spirit who prepares the Black body to be born anew through the beliefs and practices of our ancestors who knew that to be Black was to be holy. “Let Black be synonymous with glory,” she says in a voiceover early in the film. Efi Chalikopoulou The Top 100 Beyoncé Songs, Ranked Beyoncé’s evolution from entertainer to pop icon truly began with her 2013 visual album Beyoncé, a public baptism into heritage and identity that humanized the most powerful woman in the music industry and documented her reclamation of a feminist personality. Her ideological foundation was further developed by womanist philosophies about lineage and reconciliation with her ancestors in Lemonade, her 2016 album that explored marital fidelity and forgiveness in the Black South, the birthplace of Black America. -

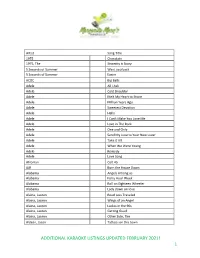

Additional Karaoke Listings Updated February 2021! 1

Artist Song Title 1975 Chocolate 1975, The Sincerity is Scary 5 Seconds of Summer Want you back 5 Seconds of Summer Easier ACDC Big Balls Adele All I Ask Adele Cold Shoulder Adele Melt My Heart to Stone Adele Million Years Ago Adele Sweetest Devotion Adele Hello Adele I Can't Make You Love Me Adele Love in The Dark Adele One and Only Adele Send My Love to Your New Lover Adele Take It All Adele When We Were Young Adele Remedy Adele Love Song Afroman Colt 45 AJR Burn the House Down Alabama Angels Among us Alabama Forty Hour Week Alabama Roll on Eighteen Wheeler Alabama Lady down on love Alaina, Lauren Road Less Traveled Alaina, Lauren Wings of an Angel Alaina, Lauren Ladies in the 90s Alaina, Lauren Getting Good Alaina, Lauren Other Side, The Aldean, Jason Tattoos on this town ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 1 Aldean, Jason Just Getting Started Aldean, Jason Lights Come On Aldean, Jason Little More Summertime, A Aldean, Jason This Plane Don't Go There Aldean, Jason Tonight Looks Good On You Aldean, Jason Gettin Warmed up Aldean, Jason Truth, The Aldean, Jason You make it easy Aldean, Jason Girl Like you Aldean, Jason Camouflage Hat Aldean, Jason We Back Aldean, Jason Rearview Town Aldean, Jason & Miranda Lambert Drowns The Whiskey Alice in Chains Man In The Box Alice in Chains No Excuses Alice in Chains Your Decision Alice in Chains Nutshell Alice in Chains Rooster Allan, Gary Every Storm (Runs Out of Rain) Allan, Gary Runaway Allen, Jimmie Best shot Anderson, John Swingin' Andress, Ingrid Lady Like Andress, Ingrid More Hearts Than Mine Angels and Airwaves Kiss & Tell Angston, Jon When it comes to loving you Animals, The Bring It On Home To Me Arctic Monkeys Do I Wanna Know Ariana Grande Breathin Arthur, James Say You Won't Let Go Arthur, James Naked Arthur, James Empty Space ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 2 Arthur, James Falling like the stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite the Stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite The Stars Ashanti Happy Ashanti Helpless (ft. -

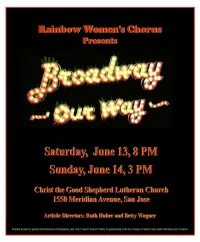

Broadway-Our-Way-2015.Pdf

Our Mission Rainbow Women’s Chorus works together to develop musical excellence in an atmosphere of mutual support and respect. We perform publicly for the entertainment, education and cultural enrichment of our audiences and community. We sing to enhance the esteem of all women, to celebrate diversity, to promote peace and freedom, and to touch people’s hearts and lives. Our Story Rainbow Women’s Chorus is a nonprofit corporation governed by the Action Circle, a group of women dedicated to realizing the organization’s mission. Chorus members began singing together in 1996, presenting concerts in venues such as Christ the Good Shepherd Lutheran Church, Le Petit Trianon Theatre, the San Jose Repertory Theater and Triton Museum. The chorus also performs at church services, diversity celebrations, awards ceremonies, community meetings and private events. Rainbow Women’s Chorus is a member of the Gay and Lesbian Association of Choruses (GALA). In 2000, RWC proudly co-hosted GALA Festival in San Jose, with the Silicon Valley Gay Men’s Chorus. Since then, RWC has participated in GALA Festivals in Montreal (2004), Miami (2008), and Denver (2012). In February 2006, members of RWC sang at Carnegie Hall in NYC with a dozen other choruses for a breast cancer and HIV benefit. In July 2010, RWC traveled to Chicago for the Sister Singers Women’s Choral Festival. But we like it best when we are here at home, singing for you! Support the Arts Rainbow Women’s Chorus and other arts organizations receive much valued support from Silicon Valley Creates, not only in grants, but also in training, guidance, marketing, fundraising, and more.