GNB: Gamakas No Bar -.:: GEOCITIES.Ws

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rakti in Raga and Laya

VEDAVALLI SPEAKS Sangita Kalanidhi R. Vedavalli is not only one of the most accomplished of our vocalists, she is also among the foremost thinkers of Carnatic music today with a mind as insightful and uncluttered as her music. Sruti is delighted to share her thoughts on a variety of topics with its readers. Rakti in raga and laya Rakti in raga and laya’ is a swara-oriented as against gamaka- complex theme which covers a oriented raga-s. There is a section variety of aspects. Attempts have of exponents which fears that ‘been made to interpret rakti in the tradition of gamaka-oriented different ways. The origin of the singing is giving way to swara- word ‘rakti’ is hard to trace, but the oriented renditions. term is used commonly to denote a manner of singing that is of a Yo asau Dhwaniviseshastu highly appreciated quality. It swaravamavibhooshitaha carries with it a sense of intense ranjako janachittaanaam involvement or engagement. Rakti Sankarabharanam or Bhairavi? rasa raga udaahritaha is derived from the root word Tyagaraja did not compose these ‘ranj’ – ranjayati iti ragaha, ranjayati kriti-s as a cluster under the There is a reference to ‘dhwani- iti raktihi. That which is pleasing, category of ghana raga-s. Older visesha’ in this sloka from Brihaddcsi. which engages the mind joyfully texts record these five songs merely Scholars have suggested that may be called rakti. The term rakti dhwanivisesha may be taken th as Tyagaraja’ s compositions and is not found in pre-17 century not as the Pancharatna kriti-s. Not to connote sruti and that its texts like Niruktam, Vyjayanti and only are these raga-s unsuitable for integration with music ensures a Amarakosam. -

Carnatic Music (Melodic Instrumental) (Code No

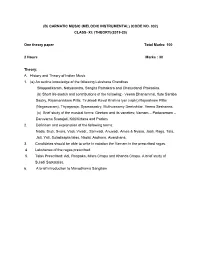

(B) CARNATIC MUSIC (MELODIC INSTRUMENTAL) (CODE NO. 032) CLASS–XI: (THEORY)(2019-20) One theory paper Total Marks: 100 2 Hours Marks : 30 Theory: A. History and Theory of Indian Music 1. (a) An outline knowledge of the following Lakshana Grandhas Silappadikaram, Natyasastra, Sangita Ratnakara and Chaturdandi Prakasika. (b) Short life sketch and contributions of the following:- Veena Dhanammal, flute Saraba Sastry, Rajamanikkam Pillai, Tirukkodi Kaval Krishna lyer (violin) Rajaratnam Pillai (Nagasvaram), Thyagaraja, Syamasastry, Muthuswamy Deekshitar, Veena Seshanna. (c) Brief study of the musical forms: Geetam and its varieties; Varnam – Padavarnam – Daruvarna Svarajati, Kriti/Kirtana and Padam 2. Definition and explanation of the following terms: Nada, Sruti, Svara, Vadi, Vivadi:, Samvadi, Anuvadi, Amsa & Nyasa, Jaati, Raga, Tala, Jati, Yati, Suladisapta talas, Nadai, Arohana, Avarohana. 3. Candidates should be able to write in notation the Varnam in the prescribed ragas. 4. Lakshanas of the ragas prescribed. 5. Talas Prescribed: Adi, Roopaka, Misra Chapu and Khanda Chapu. A brief study of Suladi Saptatalas. 6. A brief introduction to Manodhama Sangitam CLASS–XI (PRACTICAL) One Practical Paper Marks: 70 B. Practical Activities 1. Ragas Prescribed: Mayamalavagowla, Sankarabharana, Kharaharapriya, Kalyani, Kambhoji, Madhyamavati, Arabhi, Pantuvarali Kedaragaula, Vasanta, Anandabharavi, Kanada, Dhanyasi. 2. Varnams (atleast three) in Aditala in two degree of speed. 3. Kriti/Kirtana in each of the prescribed ragas, covering the main Talas Adi, Rupakam and Chapu. 4. Brief alapana of the ragas prescribed. 5. Technique of playing niraval and kalpana svaras in Adi, and Rupaka talas in two degrees of speed. 6. The candidate should be able to produce all the gamakas pertaining to the chosen instrument. -

Andhra University 1 Year Diploma in (Music) Syllabus

SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATIN – ANDHRA UNIVERSITY 1st YEAR DIPLOMA IN (MUSIC) SYLLABUS (BOS approved and modified syllabus to be implemented from the admitted Batch 2012-13) Theory 100 Marks Paper I : Technical aspects of South Indian Classical Music 1. Technical Terms: a) Nada b) Sruti c) Swaras d) Swarasthanas e) Sathayi 2. Tala System: Sapta Talas, 35 Talas, Tala Dasa Prans, Chapu Tala Varieties Desadi and Madhyadi Talas 3. Musical Forms and their Lakshnas: Gitam, Varnam, Kritis, Kirtana, Padam, Ragamalika, Jasti Swaram, Swarajati, Tillana and Javali. 4. Lakshanas and Sancharas of the following Ragas: A a) Todi, b) Mayamalavagoula, c) Bhairavi, d) Kambhoji, e) Sankarabharanam f) Kalyani, g) Kharaharapriya, h) Mohana, i) Madhyamavathi j) Bilahari B. a) Dhanyasi, b) Saveri e)Vasanta d) HIndola e) Ananda Bhairavi f) Mukhari g) Kanada h) Khamas i) Begada j) Poorikalyani Paper II : Theoretical Aspects of South Indian Classical Music 100 Marks 1. Raaga and raga Lakshanam: a) Definition and Classification of ragas. b) Study of 13 Lakshanas c) ragalapana Padhathi 2. Musical Instruments and their classification 3. Special study of Tambura, Veena, Violin, Flute, Nagaswaram and Mridangam. 4. Characteristics of a composer. 5. Short biographical sketches of the following: a) Jayadeva b) Annamayya, c) Purandhara Dasa d) Narayana Tirtha e) Ramadasa f) Kshetrayya. Practical (First year) 100 Marks Paper III (Practical I) Fundamentals of Classical Music 1. a. Saraliswaras 6 b. Janta swaras 8 c. Alankaras 7 2. Gitas - 7 (Two Pillari Gitas, Two Ghanaraga Gitas, one Dhruva and one Lakshana gitam) 3. One Swarapallavi and one Swarajati 4. Five Adi Tala Varnas. -

University of Kerala Ba Music Faculty of Fine Arts Choice

UNIVERSITY OF KERALA COURSE STRUCTURE AND SYLLABUS FOR BACHELOR OF ARTS DEGREE IN MUSIC BA MUSIC UNDER FACULTY OF FINE ARTS CHOICE BASED-CREDIT-SYSTEM (CBCS) Outcome Based Teaching, Learning and Evaluation (2021 Admission onwards) 1 Revised Scheme & Syllabus – 2021 First Degree Programme in Music Scheme of the courses Sem Course No. Course title Inst. Hrs Credit Total Total per week hours credits I EN 1111 Language course I (English I) 5 4 25 17 1111 Language course II (Additional 4 3 Language I) 1121 Foundation course I (English) 4 2 MU 1141 Core course I (Theory I) 6 4 Introduction to Indian Music MU 1131 Complementary I 3 2 (Veena) SK 1131.3 Complementary course II 3 2 II EN 1211 Language course III 5 4 25 20 (English III) EN1212 Language course IV 4 3 (English III) 1211 Language course V 4 3 (Additional Language II) MU1241 Core course II (Practical I) 6 4 Abhyasaganam & Sabhaganam MU1231 Complementary III 3 3 (Veena) SK1231.3 Complementary course IV 3 3 III EN 1311 Language course VI 5 4 25 21 (English IV) 1311 Language course VII 5 4 (Additional language III ) MU1321 Foundation course II 4 3 MU1341 Core course III (Theory II) 2 2 Ragam MU1342 Core course IV (Practical II) 3 2 Varnams and Kritis I MU1331 Complementary course V 3 3 (Veena) SK1331.3 Complementary course VI 3 3 IV EN 1411 Language course VIII 5 4 25 21 (English V) 1411 Language course IX 5 4 (Additional language IV) MU1441 Core course V (Theory III) 5 3 Ragam, Talam and Vaggeyakaras 2 MU1442 Core course VI (Practical III) 4 4 Varnams and Kritis II MU1431 Complementary -

CARNATIC MUSIC Melodic Instrument - (Code No

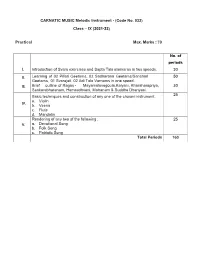

CARNATIC MUSIC Melodic Instrument - (Code No. 032) Class – IX (2021-22) Practical Max. Marks : 70 No. of periods I. Introduction of Svara exercises and Sapta Tala alankaras in two speeds. 30 II. Learning of 02 Pillari Geetams, 02 Sadharana Geetams/Sanchari 50 Geetams, 01 Svarajati, 02 Adi Tala Varnams in one speed. III. Brief outline of Ragas - Mayamalavagoula,Kalyani, Kharaharapriya, 30 Sankarabharanam, Hamsadhvani, Mohanam & Suddha Dhanyasi. Basic techniques and construction of any one of the chosen instrument. 25 a. Violin IV. b. Veena c. Flute d. Mandolin Rendering of any two of the following : 25 V. a. Devotional Song b. Folk Song c. Patriotic Song Total Periods 160 CARNATIC MUSIC Melodic Instrument - (Code No. 032) Format for Practical Examination for Class – IX Practical Max. Marks : 70 I. Questions based on the rendering of Swara Execises 10 marks and Sapta Tala alankaras in two speeds. II. Questions based on Gitams, Swarajati and Varnam 10 marks III. Brief explanation of Ragas from the syllabus. 10 marks IV. Questions based on the chosen instrument 08 marks V. Rendering in part or full of the compositions from the 07 marks topic V. VI. Reciting the Sahitya or lyric of the compositions learnt 05 marks Marks 50 Marks Internal Assessment 20 marks 70 marks CARNATIC MUSIC Melodic Instrument - (Code No. 032) Format for Examination for Class – IX (2021-22) Theory Max. Marks: 30 Time: 2 hours I Section I i 6 MCQ based on all above mentioned topics. 6 marks II Section II i Notation of any one Gitam 6 marks ii Brief lakshanas of any two -

Carnatic Music Theory Year I

CARNATIC MUSIC THEORY YEAR I BASED ON THE SYLLABUS FOLLOWED BY GOVERNMENT MUSIC COLLEGES IN ANDHRA PRADESH AND TELANGANA FOR CERTIFICATE EXAMS HELD BY POTTI SRIRAMULU TELUGU UNIVERSITY ANANTH PATTABIRAMAN EDITION: 2.6 Latest edition can be downloaded from https://beautifulnote.com/theory Preface This text covers topics on Carnatic music required to clear the first year exams in Government music colleges in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. Also, this is the first of four modules of theory as per Certificate in Music (Carnatic) examinations conducted by Potti Sriramulu Telugu University. So, if you are a music student from one of the above mentioned colleges, or preparing to appear for the university exam as a private candidate, you’ll find this useful. Though attempts are made to keep this text up-to-date with changes in the syllabus, students are strongly advised to consult the college or univer- sity and make sure all necessary topics are covered. This might also serve as an easy-to-follow introduction to Carnatic music for those who are generally interested in the system but not appearing for any particular examination. I’m grateful to my late guru, veteran violinist, Vidwan. Peri Srirama- murthy, for his guidance in preparing this document. Ananth Pattabiraman Editions First published in 2009, editions 2–2.2 in 2017, 2.3–2.5 in 2018, 2.6 in 2019. Latest edition available at https://beautifulnote.com/theory Copyright This work is copyrighted and is distributed under Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 license. You can make copies and share freely. -

Rāga Recognition Based on Pitch Distribution Methods

Rāga Recognition based on Pitch Distribution Methods Gopala K. Koduria, Sankalp Gulatia, Preeti Raob, Xavier Serraa aMusic Technology Group, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain. bDepartment of Electrical Engg., Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, Mumbai, India. Abstract Rāga forms the melodic framework for most of the music of the Indian subcontinent. us automatic rāga recognition is a fundamental step in the computational modeling of the Indian art-music traditions. In this work, we investigate the properties of rāga and the natural processes by which people identify it. We bring together and discuss the previous computational approaches to rāga recognition correlating them with human techniques, in both Karṇāṭak (south Indian) and Hindustānī (north Indian) music traditions. e approaches which are based on first-order pitch distributions are further evaluated on a large com- prehensive dataset to understand their merits and limitations. We outline the possible short and mid-term future directions in this line of work. Keywords: Indian art music, Rāga recognition, Pitch-distribution analysis 1. Introduction ere are two prominent art-music traditions in the Indian subcontinent: Karṇāṭak in the Indian peninsular and Hindustānī in north India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. Both are orally transmied from one generation to another, and are heterophonic in nature (Viswanathan & Allen (2004)). Rāga and tāla are their fundamental melodic and rhythmic frameworks respectively. However, there are ample differ- ences between the two traditions in their conceptualization (See (Narmada (2001)) for a comparative study of rāgas). ere is an abundance of musicological resources that thoroughly discuss the melodic and rhythmic concepts (Viswanathan & Allen (2004); Clayton (2000); Sambamoorthy (1998); Bagchee (1998)). -

Academy of Fine Arts (London) Public Examination

ACADEMY OF FINE ARTS (LONDON) PUBLIC EXAMINATION in CARNATIC MUSIC VOCAL & I STRUME TAL 5th May 2007 Grade Five Total time: Two and half hours YOUR FULL NAME: ______________________________________________________ YOUR REGISTRATION NO .________________________________________________ • Please write your full name and Registration No. on your answer script and on this question paper. Attach this question paper with your answer scripts. Answer all Questions Part One - Must be answered on the question paper Underline the correct word from the terms given in brackets 1. The third section in a kirtana is (idai nilai, charanam, ettukadai pallavi) 2. Tisrajati Rupakam and Khanda jati Eka talam, each have (7, 3, 5) aksharams to an avartam. 3. Pantuvarali and Simhendra madhyamam, have the same fourth swaram in their arohanam because they are (uttaranga melas, purvanga melas, prashidha melas) 4. Dhanyasi and Hindolam are janya ragas of the (8 th and 20 th melas respectively, 8th and 15 th melas respectively) 5. Ghatam and Kanchira belong to the section called (sushira vadyams, pratama vadyams, tala vadyams) 6. A Melakarta ragam, whose arohanam-avarohanam has all the suddha swaram is (Thodi, Kanagangi, Chakravakam) 7. Ashtapadis are musical pieces composed by (Bharatiar, Jayadevar, Thiyagarajah) 8. Arunachala Kavirayar’s compositions are all in (Tamil, Telugu, Hindi) 9. The mela mnemonics in the 72 melakarta scheme are (7, 6, 12) in each chakra. 10. Thillanas contain (Jatis, swarakorvai, kalpanaswarams) in their structures. (10 x 2 = 20 marks) (Continued on the next page) ACADEMY OF FINE ARTS (LONDON) PUBLIC EXAMINATION in CARNATIC MUSIC VOCAL & I STRUME TAL 5th May 2007 Grade 5 Please write your full name on your answer scripts as well. -

Vol.74-76 2003-2005.Pdf

ISSN. 0970-3101 THE JOURNAL Of THE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS Devoted to the Advancement of the Science and Art of Music Vol. LXXIV 2003 ^ JllilPd frTBrf^ ^TTT^ II “I dwell not in Vaikunta, nor in the hearts of Yogins, not in the Sun; (but) where my Bhaktas sing, there be /, N arada !” Narada Bhakti Sutra EDITORIAL BOARD Dr. V.V. Srivatsa (Editor) N. Murali, President (Ex. Officio) Dr. Malathi Rangaswami (Convenor) Sulochana Pattabhi Raman Lakshmi Viswanathan Dr. SA.K. Durga Dr. Pappu Venugopala Rao V. Sriram THE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS New No. 168 (Old No. 306), T.T.K. Road, Chennai 600 014. Email : [email protected] Website : www.musicacademymadras.in ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION - INLAND Rs. 150 FOREIGN US $ 5 Statement about ownership and other particulars about newspaper “JOURNAL OF THE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS” Chennai as required to be published under Section 19-D sub-section (B) of the Press and Registration Books Act read with rule 8 of the Registration of Newspapers (Central Rules) 1956. FORM IV JOURNAL OF THE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS Place of Publication Chennai All Correspondence relating to the journal should be addressed Periodicity of Publication and all books etc., intended for it should be sent in duplicate to the Annual Editor, The journal o f the Music Academy Madras, New 168 (Old 306), Printer Mr. N Subramanian T.T.K. Road, Chennai 600 014. 14, Neelakanta Mehta Street Articles on music and dance are accepted for publication on the T Nagar, Chennai 600 017 recommendation of the Editor. The Editor reserves the right to accept Publisher Dr. -

Department of Indian Music Name of the PG Degree Program

Department of Indian Music Name of the PG Degree Program: M.A. Indian Music First Semester FPAC101 Foundation Course in Performance – 1 (Practical) C 4 FPAC102 Kalpita Sangita 1 (Practical) C 4 FPAC103 Manodharma Sangita 1 (Practical) C 4 FPAC114 Historical and Theoretical Concepts of Fine Arts – 1 C 4 ( Theory) FPAE101 Elective Paper 1 - Devotional Music - Regional Forms of South India E 3 (Practical) FPAE105 Elective Paper 2 - Compositions of Muttusvami Dikshitar (Practical) E 3 Soft Skills Languages (Sanskrit and Telugu)1 S 2 Second Semester FPAC105 Foundation Course in Performance – 2 (Practical) C 4 FPAC107 Manodharma Sangita 2 (Practical) C 4 FPAC115 Historical and Theoretical Concepts of Fine Arts – 2 ( Theory) C 4 FPAE111 Elective Paper 3 - Opera – Nauka Caritram (Practical) E 3 FPAE102 Elective Paper 4 - Nandanar caritram (Practical) E 3 FPAE104 Elective Paper 5 – Percussion Instruments (Theory) E 3 Soft Skills Languages (Kannada and Malayalam)2 S 2 Third Semester FPAC108 Foundation Course in Performance – 3 (Practical) C 4 FPAC106 Kalpita Sangita 2 (Practical) C 4 FPAC110 Alapana, Tanam & Pallavi – 1 (Practical) C 4 FPAC116 Advanced Theory – Music (Theory) C 4 FPAE106 Elective Paper 6 - Compositions of Syama Sastri (Practical) E 3 FPAE108 Elective Paper 7 - South Indian Art Music - An appreciation (Theory) E 3 UOMS145 Source Readings-Selected Verses and Passages from Tamiz Texts ( S 2 Theory) uom1001 Internship S 2 Fourth Semester FPAC117 Research Methodology (Theory) C 4 FPAC112 Project work and Viva Voce C 8 FPAC113 Alapana, -

CARNATIC MUSIC (VOCAL) (Code No

CARNATIC MUSIC (VOCAL) (code no. 031) Class IX (2020-21) Theory Marks: 30 Time: 2 Hours No. of periods I. Brief history of Carnatic Music with special reference to Saint 10 Purandara dasa, Annamacharya, Bhadrachala Ramadasa, Saint Tyagaraja, Muthuswamy Dikshitar, Syama Sastry and Swati Tirunal. II. Definition of the following terms: 12 Sangeetam, Nada, raga, laya, Tala, Dhatu, Mathu, Sruti, Alankara, Arohana, Avarohana, Graha (Sama, Atita, Anagata), Svara – Prakruti & Vikriti Svaras, Poorvanga & Uttaranga, Sthayi, vadi, Samvadi, Anuvadi & Vivadi Svara – Amsa, Nyasa and Jeeva. III. Brief raga lakshanas of Mohanam, Hamsadhvani, Malahari, 12 Sankarabharanam, Mayamalavagoula, Bilahari, khamas, Kharaharapriya, Kalyani, Abhogi & Hindolam. IV. Brief knowledge about the musical forms. 8 Geetam, Svarajati, Svara Exercises, Alankaras, Varnam, Jatisvaram, Kirtana & Kriti. V. Description of following Talas: 8 Adi – Single & Double Kalai, Roopakam, Chapu – Tisra, Misra & Khanda and Sooladi Sapta Talas. VI. Notation of Gitams in Roopaka and Triputa Tala 10 Total Periods 60 CARNATIC MUSIC (VOCAL) Format of written examination for class IX Theory Marks: 30 Time: 2 Hours 1 Section I Six MCQ based on all the above mentioned topic 6 Marks 2 Section II Notation of Gitams in above mentioned Tala 6 Marks Writing of minimum Two Raga-lakshana from prescribed list in 6 Marks the syllabus. 3 Section III 6 marks Biography Musical Forms 4 Section IV 6 marks Description of talas, illustrating with examples Short notes of minimum 05 technical terms from the topic II. Definition of any two from the following terms (Sangeetam, Nada, Raga,Sruti, Alankara, Svara) Total Marks 30 marks Note: - Examiners should set atleast seven questions in total and the students should answer five questions from them, including two Essays, two short answer and short notes questions based on technical terms will be compulsory. -

Raga (Melodic Mode) Raga This Article Is About Melodic Modes in Indian Music

FREE SAMPLES FREE VST RESOURCES EFFECTS BLOG VIRTUAL INSTRUMENTS Raga (Melodic Mode) Raga This article is about melodic modes in Indian music. For subgenre of reggae music, see Ragga. For similar terms, see Ragini (actress), Raga (disambiguation), and Ragam (disambiguation). A Raga performance at Collège des Bernardins, France Indian classical music Carnatic music · Hindustani music · Concepts Shruti · Svara · Alankara · Raga · Rasa · Tala · A Raga (IAST: rāga), Raag or Ragam, literally means "coloring, tingeing, dyeing".[1][2] The term also refers to a concept close to melodic mode in Indian classical music.[3] Raga is a remarkable and central feature of classical Indian music tradition, but has no direct translation to concepts in the classical European music tradition.[4][5] Each raga is an array of melodic structures with musical motifs, considered in the Indian tradition to have the ability to "color the mind" and affect the emotions of the audience.[1][2][5] A raga consists of at least five notes, and each raga provides the musician with a musical framework.[3][6][7] The specific notes within a raga can be reordered and improvised by the musician, but a specific raga is either ascending or descending. Each raga has an emotional significance and symbolic associations such as with season, time and mood.[3] The raga is considered a means in Indian musical tradition to evoke certain feelings in an audience. Hundreds of raga are recognized in the classical Indian tradition, of which about 30 are common.[3][7] Each raga, state Dorothea