ADRIAN RUSSELL Journey, with Extensive Interviews from Those at the Centre of This Piece of Sporting History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Football Club Years Of

125YEARS OF Cork Constitution FOOTBALL CLUB Edmund Van Esbeck Published by Cork Constitution Football Club, Temple Hill, Cork. Tel: 021 4292 563 i Cork Constitution Football Club wishes to sincerely thank the author, Edmund Van Esbeck and gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the following in the publication of this book: PHOTOGRAPHS Irish Examiner Archieve Sportsfile Photography Inpho Photography Colin Watson Photographey,Montreal, Canada John Sheehan Photography KR Events Martin O’Brien The Framemaker Club Members © Copyright held by suppliers of photographs GRAPHIC DESIGN Nutshell Creative Communication PRINTER Watermans Printers, Little Island, Co. Cork. ii AUTHORS NOTE & ACKNOWLEDGEMENT When the Cork Constitution Club celebrated the centenary of its foundation I had the privilege of writing the history. Now I have been entrusted with updating that chronicle. While obviously the emphasis will be on the events of the last twenty-five years - the most momentous period in the history of rugby union - as a tribute to the founding fathers, the first chapter of the original history will yet again appear. While it would not be practical to include a detailed history of the first 100 years chapter two is a brief resume of the achievements of the first fifty years and likewise chapter three embraces the significant events of the second fifty years in the illustrious history of one of Ireland’s great sporting institutions. There follows the detailed history and achievements, and they were considerable, of the last twenty five years. I owe a considerable debt of gratitude to many people for their help during the compilation of this book. In that regard I would particularly like to thank Noel Walsh, the man with whom I liaised during the writing of the book. -

17 Meán Fómhair, 2010 1 NUACHT NÁISIÚNTA Nuacht “Tá Seans Na Nóg

www.gaelsceal.ie Micheál Ó Laoch Muircheartaigh ag Litríochta éirí as - labhraíonn na nGael sé le Gaelscéal L. 7 Crann Beag L. 31 na nEalaíon L. 22 €1.65 (£1.50) Ag Cothú Phobal na Gaeilge 17.09.2010 Uimh. 26 • IDIRNÁISIÚNTA Gaeilge ag Athraithe Móra i ndán do SAM 30% de Seán Ó Curraighín, in Minnesota, SAM TÁ cuma ar chúrsaí go mbeidh athruithe móra pháistí na ar leagan amach na cumhachta sna Stáit Aontaithe sa toghchán lár téarma ag tús Samh- na. Tá na Poblachtaigh ar ríocht cumhacht a Gaeltachta bhaint amach i dTeach na nIonadaithe agus iad Anailís le Donncha Ó hÉallaithe Thart ar 10,000 teaghlach le gar don éacht céanna sa páistí scoile atá sa Ghaeltacht Seanad, dar le D’ÉIRIGH le 2,326 (70%) den 3,355 oifigiúil. 6,500 acu, ní bhacann pobalbhreith Washing- teaghlach Gaeltachta a rinne iar- siad le hiarratas a dhéanamh, mar ton Post-ABC. ratas faoi Scéim Labhairt na go dtuigeann a bhformhór nach In agallamh le Gaeilge, an deontas iomlán a fháil bhfuil a ndóthain Gaeilge ag a Gaelscéal, dúirt an tOl- anuraidh agus tugadh an deontas gcuid gasúr le cur isteach ar an lamh le hEolaíocht Pho- laghdaithe do 449 (13%) eile. scéim. laitiúil i UST, Minnesota, Nuair a deirtear ar an gcaoi sin é, Is é fírinne an scéil go léiríonn na Nancy Zingale, go gcaill- tá an chuma air go bhfuil líofacht figiúirí ón SLG 2009/10 go bhfuil fidh na Daonlathaigh Ghaeilge ag formhór na ndaltaí líofacht mhaith Ghaeilge ag thart cumhacht an tromlaigh i scoile sa Ghaeltacht. -

2010 League Presentations Dates for Your Diary GAA Email GAA Season

th Nuachtlitir Coiste Chontae Chorcaí: Vol. 2 No. 26, December 14 2010 Dates for Your 2010 League Presentations GAA Email Diary The presentation of cheques to the successful teams in Just a reminder: 16th December: Cork this year's RedFM Senior Hurling League took recently in where clubs have a GAA Clubs’ Draw, the RedFM Studios. In all, €11,000 was presented to change of secretary, Mitchelstown seven clubs - the top six, Midleton, Erin's Own, Sars, please ensure the th Killeagh, Na Piarsaigh and Glen Rovers, plus new secretary gets 20 December: Presentation of Bishopstown who completed their full league access to the GAA Munster Council programme and were thus entered into a draw for Email address. For Grants, time and €1000. County Chairman Jerry O'Sullivan and PRO any queries, contact venue tbc Gerard Lane both expressed their gratitude to Fiona [email protected] Darcy (CEO) and all at RedFM for their generous sponsorship of this competition. GAA Season 2011 Ticket 2011 Competitions The 2011 GAA The draws for the Season Ticket is now 2011 Evening Echo County Chairman Jerry O’Sullivan presents Midleton with their County on sale at a base price winners’ cheque. Also included are Fiona Darcy, Red FM CEO, and Pat of €75 (Juveniles Horgan, SHL Chairman. Championships €10). Rounds 1 and 2 were Cheques were also presented to the winners and made at Convention The Season Ticket th Scheme offers huge runners-up of all the other leagues at a recent function on December 12 – savings to fans, and is in Rochestown Park Hotel, where a total €29,725 was click here to view the available for either distributed between thirteen clubs. -

Claremen & Women in the Great War 1914-1918

Claremen & Women in The Great War 1914-1918 The following gives some of the Armies, Regiments and Corps that Claremen fought with in WW1, the battles and events they died in, those who became POW’s, those who had shell shock, some brothers who died, those shot at dawn, Clare politicians in WW1, Claremen courtmartialled, and the awards and medals won by Claremen and women. The people named below are those who partook in WW1 from Clare. They include those who died and those who survived. The names were mainly taken from the following records, books, websites and people: Peadar McNamara (PMcN), Keir McNamara, Tom Burnell’s Book ‘The Clare War Dead’ (TB), The In Flanders website, ‘The Men from North Clare’ Guss O’Halloran, findagrave website, ancestry.com, fold3.com, North Clare Soldiers in WW1 Website NCS, Joe O’Muircheartaigh, Brian Honan, Kilrush Men engaged in WW1 Website (KM), Dolores Murrihy, Eric Shaw, Claremen/Women who served in the Australian Imperial Forces during World War 1(AI), Claremen who served in the Canadian Forces in World War 1 (CI), British Army WWI Pension Records for Claremen in service. (Clare Library), Sharon Carberry, ‘Clare and the Great War’ by Joe Power, The Story of the RMF 1914-1918 by Martin Staunton, Booklet on Kilnasoolagh Church Newmarket on Fergus, Eddie Lough, Commonwealth War Grave Commission Burials in County Clare Graveyards (Clare Library), Mapping our Anzacs Website (MA), Kilkee Civic Trust KCT, Paddy Waldron, Daniel McCarthy’s Book ‘Ireland’s Banner County’ (DMC), The Clare Journal (CJ), The Saturday Record (SR), The Clare Champion, The Clare People, Charles E Glynn’s List of Kilrush Men in the Great War (C E Glynn), The nd 2 Munsters in France HS Jervis, The ‘History of the Royal Munster Fusiliers 1861 to 1922’ by Captain S. -

HURLING WORLD Turning Point Ericson 4 the 1984 Maroon Munster Final Ahead

HURLING WORLD Turning Point Ericson 4 The 1984 Maroon Munster Final Ahead Hurling in Weekend Dubai Round Up ISSUE 5 1st June 2009 EDITOR’S COMMENT HURLING WORLD ISSUE THREE p 2 Hello Hurling Fans, The Guinness Hurling Championship kicked off this weekend with 2 matches in Leinster where Wexford with 2 Steven Banville goals beat Offaly and Galway gave a flawless display against Laois. The game of the weekend of course was in Munster where the hallowed ground of Semple Stadium hosted Cork and Tipperary. Benefits of joining Tipperary had the advantage of a solid League Final display against Kilkenny under their belt, while Cork are in the process of our free mailing list putting the recent turmoil behind them. 1. You will be sure of getting Though Tipp had a 3 point win in the end - both teams will be Steven banville your ezine early every pleased with their performances. The Premier County are Monday morning. improving with every game they play. The team is young fast and skillful. It is still a little bit green around the edges conceding too Contents Issue Five 2. You can take part in all our many silly frees that are always punished nowadays. They now competitions. face Clare in the Munster semi-final. 2. Editorial Comment. 3. You will be able to enter Cork were a little match rusty and might have gone on to win the our draws for All Ireland game if they had taken all their chances. Against a younger and 3. Feature. faster team, Cork had to change their style and cut out their old Tickets. -

Update from the Sports Office

Update from the Sports Office The Sports Bursary Scheme has gone from strength to strength.This year saw 105 bursaries presented to student athletes across 18 different sports. The presentation evening took place on the 30th of November with guest speaker Sue Ronan. Sue Ronan made her international debut against Sweden in 1988, she has gone on to manage the Irish U16, U18 and is currently Senior Women’s Soccer Manager. Athletics Club jumped straight into winter training. Resident coach and staff member Ian O’Sullivan is joined by Eamonn Flanagan (Events Coach) and Liam O’Reilly (Conditioning Coach). The club retained its U’23 County Title and came in 6th position in the Novice in Conna in October. The Road Relays in Maynooth took place in November with CIT sending 2 men’s teams and a full women’s team for the first time in a number of years. The Hockey & Golf teams dived straight into competition with both Varsities taking place in October. The golfers faced tough competition in Tramore drawing NUI Maynooth, UCD, and UCC in their pool. None the less, first year student, John Hickey, finished in the top 10 overall. The Hockey Club travelled to Galway with a strong Men’s and Ladies Squad. The Men’s team won the Mauritius Plate after a titanic battle against Trinity College Dublin. The women’s team drew a tough pool with UL, UCD, and UL. They came close to taking UCC scoring 1 goal to their 3. (L-R) John Hobbs, Roger Gray, Harry Flemming and Alastair Smith. -

Hurling Final Programme

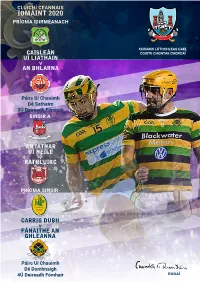

CLUICHÍ CEANNAIS IOMÁINT 2020 PRÍOMA IDIRMÉANACH CUMANN LÚTHCHLEAS GAEL CAISLEÁN COISTE CHONTAE CHORCAÍ UÍ LIATHÁIN V AN BHLARNA Páirc Uí Chaoimh Dé Sathairn 3Ú Deireadh Fómhair SINSIR A AN tATHAR UÍ NEILL V RATHLUIRC PRÍOMA SINSIR CARRIG DUBH V FÁNAITHE AN GHLEANNA Páirc Uí Chaoimh Dé Domhnaigh 4Ú Deireadh Fómhair RUNAÍ The voice of all things local, from news to sport to community and culture CORK SENIOR HURLING CHAMPIONSHIP 2020 Teachtaireacht an Chathaoirligh Is mór an deireadh seachtaine atá againn i bPáirc unqualified success. Well done to everyone Uí Chaoimh. Tá súil agam go mbainfidh gach involved in running the championship, and duine taitneamh as na gcluichí, agus cuirim fáilte particularly to our Runaí, Kevin O’Donovan, who spéisialta roimh na fóirne, na h-oifigigh, na réiteoiri has borne the bulk of the administrative efforts agus a fhóirne – táim cinnte go mbeidh sár cluichí required. I We have enjoyed some of the most spóirtúil againn. tightly-contested competitions in years, and I look forward to the benefits for our county as we move What a huge weekend of GAA action we have in forward with the format. store for us this weekend, even though most of us will be watching on TV or on the Irish Examiner In this very strange year, I would like to compliment live stream rather than here in person! Our feast all our clubs on their efforts in supporting their of finals in the Co-op Superstores County Hurling communities during the Covid-19 crisis. It has been Championships begins on Saturday night with difficult for everyone, but you have made the very Blarney meeting Castleyons in the Premier best of a tough situation. -

Celebrating 101 Years

GAA Performance Analysis Seminar 4th February 2013 18:00 – 22:00 Mardyke Arena, University College Cork, Ireland Target Audience The Seminar aims to attract all key coaches/personnel involved in GAA clubs at all levels. The Seminar will highlight the significance of performance analysis within the game and the benefits it can bring to both teams and players. Proposed Program 18:00 – 18:30 Registration & Tea’s and Coffee’s 18:30 – 18:45 Opening/Welcome Address Overview of our facilities/services 18:45 – 19:45 Session 1: How Video Analysis is used to improve performance in both a Hurling & Football context? o Case Study: Going through all areas of analysis and highlighting the statistical report that is prepared and how this is used to improve performance. Speaker: Len Browne, Head of Performance Analysis, Mardyke Arena Speaker: Sean O’Donnell, Cork Senior Hurling Analyst 25 Minute Presentations & 10 Minutes Q& A 19:45 – 20:30 Session 2: The Benefits of Performance Analysis within a Team Environment: Coaches/Players Perspective 1. Billy Morgan, UCC Sigerson Head Coach & Ex Cork Senior Football Manager 2. Brian Cuthbert, Bishopstown G.A.A Head Coach/Cork Senior Football Selector 3. Ger Cunningham, UCC Fresher’s Hurling Head Coach & Ex Cork Senior Hurler 4. Noel Furlong, Carrigtwohill GAA Player 10 Minutes Presentations & 5 Minutes Q&A 1 GAA Performance Analysis Seminar 4th February 2013 18:00 – 22:00 Mardyke Arena, University College Cork, Ireland 20:30 – 21:30 Session 3: Active Recovery for Players: Demonstration on Hydrotherapy, Anti- Gravity Treadmills & Fitness Testing 20:30 – 20:50 Group A: Demo on Hydrotherapy Pool Group B: Demo on Anti-Gravity Treadmills Group C: Fitness Testing – Indoor Track 20:50 – 21:10 Group A: Demo on Anti-Gravity Treadmills Group B: Fitness Testing – Indoor Track Group C: Demo on Hydrotherapy Pool 21:10 – 21:30 Group A: Fitness Testing – Indoor Track Group B: Demo on Hydrotherapy Pool Group C: Demo on Anti-Gravity Treadmills 21:30 – 22:00 General Questions & Answers Session 2 . -

Sunshine Draws Crowds to Fleadh Na Mumhan

MARIO'S MOTOR FACTORS MARY ST., DUNGARVAN CAR STEREOS Dungarvan Header From £29.95 and SOUTHERN DEMOCRAT FOR 12 MONTHS GUARANTEE Circulating throughout the County and City of Waterford, South Tipperary and South-East Cork TEL. 058/42417, anytime Vol. 50. No. 2572. FRIDAY, JULY 15, 1988. REGISTERED AT THE GENERAL TOYOTA POST OFFICE AS A NEWSPAPER PRICE 25p (inc. VAT) PENSMAN TAKES YOU ALICIA'S FLEADH CHEOIL NA lor's Hotel where a whole new MUMHAN storey has been added to the building incorporating a num- SUMMER Our heartiest congratulations ber of additional en suite bed- go this week to the members of moms. a conference room and the Committee which organised atrium. the very highly successful Fleadh And we note from the list of Cheoil na Mumhan in Dungar- applications lodged with the COMMENCES TO-DAY THURSDAY van last week-end. Although the County Council for the month Free Parking: Discs With All Purchases weather came in a mixed bag of June, one from Mr. John Mc- the crowds poured into the itown 10% DISCOUNT OFF Grath for an extension to his especially on Sunday and the oc- hotel at Clonea including, REGULAR STOCK casion proved a welcome wind- among other things. 30 new bid- fall especially for the hotels and Cotton Skirls €10.99. Cotton Jeans, plain and striped £10.99. rooms and function rooms. nubs which were packed up to Cotton Striped T-Shirts £5,99. Colton Bermuda Shorts £9.99. closing time on Sunday night. In addition, rumours have been Ladies Blouses £6.99. Fully-Lined Skirts. -

GAA Club – Overview

CIT Student GAA Club – Overview Camogie – Gaelic Football – Hurling – Ladies Gaelic Football - Handball As befits a County with Cork’s tradition in Gaelic Games, GAA has occupied a central role in the development of sport in the Cork Institute of Technology. The Cork Regional Technical College, as it was formally known until its change of title in 1997 to Cork Institute of Technology, first occupied its Bishopstown campus in September 1974. The new college buildings were officially opened by that great Cork GAA exponent and Taoiseach of the day, Mr. Jack Lynch, in December 1977. A student GAA football team was formed in 1975 and the hurling team commenced playing activities in 1976. In the same way the campus has evolved and expanded so too has the GAA Club which as well as being the oldest sporting club at the Institute, with over 400 active members is also the biggest. CIT Student GAA Club - Teams Teams and competitions played by CIT Student GAA Club during the 2019/20 Academic Year. Hurling Football Ladies Football Camogie Division 1 League Division 1 League Division 3 League Division 2 League Fitzgibbon Cup Sigerson Cup Moynihan Cup Purcell Cup Intermediate League Intermediate League Fresher Blitz Intermediate C’ship Intermediate C’ship Junior C’ship Fresher 1 League Fresher 1 League Fresher 2 League Fresher 2 League Fresher A Championship Fresher A Championship Fresher B Championship Fresher B Championship While nobody knows exactly what the new academic year of 2020/21 will bring, one thing is definite – “Nothing will work unless we do”, so if it’s on – then we’ll be ready to participate. -

Building Register Q3 2016

Building Register Q3 2016 Notice Type Notice No. Local Authority Commencement Date Description Development Location Planning Permission Validation Date Owner Name Owner Company Owner Address Builder Name Builder Company Designer Name Designer Company Certifier Name Certifier Company Completion Cert No. Number Opt Out Commencement CN0021175CW Carlow County Council 25/10/2016 OPT OUT Construction of a proposed Dunleckney, Bagenalstown, 16107 28/09/2016 Stephanie Drea Na The stables Stephanie Drea Na Stephanie Drea Na Notice extension to existing dwelling with the carlow Dunleckney provision of onsite wastewater Bagenalstown treatment system and all associated carlow R21 Hk12 site development works Opt Out Commencement CN0021226CW Carlow County Council 13/10/2016 To demolish existing single storey 7 St. Lazerian Street, 16207 29/09/2016 Michael Gillespie 44 Blackmill Street Michael Gillespie Patrick Byrne Planning & Design Notice garage to the side of existing single Leighlinbridge, carlow Kilkenny Kilkenny Solutions storey dwelling and reconstruct a kilkenny R95 D8C6 single storey extension to be used as part of existing residence (ensuite, walk in wardrobe and store ) minor external alterations to the front facade and all associated site works including widening of existing entrance and revised car parking layout at No. 7 Lazerian Street, Leighlinbridge, Co Carlow Opt Out Commencement CN0021147CW Carlow County Council 10/10/2016 Erection of a dwelling house (change Rathgeran, Borris, carlow 1627 27/09/2016 bebhinn ryan rathgueran bebhinn -

Munster Schools Athletics Champions 1931-2020 (Some Background Information on This Championship Appears at the End of the Document)

Munster Schools Athletics Champions 1931-2020 (Some background information on this championship appears at the end of the document) Forenames (with only an initial), corrections & additions to [email protected] Roll of Honour Senior Boys 100m 100yds ( 1931 - 1969 ) 1931 Michael O'Sullivan Rockwell College 10.4 100yds Senior Boys 1937 Billy Phelan Waterpark College Waterford 10.8 100yds Senior Boys 1938 Thomas Kelly Rockwell College 10.6 100yds Senior Boys 1939 T Daly St Flannans Ennis 10.6 100yds Senior Boys 1940 Michael Dunne Rockwell College 10.3 100yds Senior Boys 1941 Michael Dunne Rockwell College 10.6 100yds Senior Boys 1947 Pat Scannell Christian Brothers College Cork 11.0 100yds Senior Boys 1948 Pat Scannell Christian Brothers College Cork 10.2 100yds Senior Boys 1949 Noel Keane Rockwell College 11.0 100yds Senior Boys 1950 Noel Keane Rockwell College 10.5 100yds Senior Boys 1951 Michael Manning Rockwell College 10.5 100yds Senior Boys 1952 Michael Manning Rockwell College 10.4 100yds Senior Boys 1953 Donan Dempsey St Flannans Ennis 10.1 100yds Senior Boys 1954 Maurice Donegan Presentation Brothers Cork 10.3 100yds Senior Boys 1955 Liam Fennessy High School Clonmel 10.5 100yds Senior Boys 1956 Mick Lanigan De La Salle Waterford 10.0 100yds Senior Boys 1957 Wyndham Williams Christian Brothers College Cork 10.3 100yds Senior Boys 1958 L Silke Mungret College Limerick 10.2 100yds Senior Boys 1959 Denis Murray Rockwell College 10.4 100yds Senior Boys 1960 David Broderick Cresent Comprehensive SJ Limerick 10.6 100yds Senior