Arxiv:1011.4295V2 [Astro-Ph.GA] 24 Feb 2011 Nheacia Oddr Atrmdl Eg Ec Ta.20) the 2004)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Arxiv:1904.07129V1 [Astro-Ph.GA] 15 Apr 2019](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2255/arxiv-1904-07129v1-astro-ph-ga-15-apr-2019-72255.webp)

Arxiv:1904.07129V1 [Astro-Ph.GA] 15 Apr 2019

Draft version April 16, 2019 Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 12/16/11 SPIRE SPECTROSCOPY OF EARLY TYPE GALAXIES Ryen Carl Lapham and Lisa M. Young Physics Department, New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology, 801 Leroy Place, Socorro, NM 87801; [email protected], [email protected] Draft version April 16, 2019 ABSTRACT We present SPIRE spectroscopy for 9 early-type galaxies (ETGs) representing the most CO-rich and far-infrared (FIR) bright galaxies of the volume-limited Atlas3D sample. Our data include detections of mid to high J CO transitions (J=4-3 to J=13-12) and the [C I] (1-0) and (2-1) emission lines. CO spectral line energy distributions (SLEDs) for our ETGs indicate low gas excitation, barring NGC 1266. We use the [C I] emission lines to determine the excitation temperature of the neutral gas, as well as estimate the mass of molecular hydrogen. The masses agree well with masses derived from CO, making this technique very promising for high redshift galaxies. We do not find a trend between the [N II] 205 flux and the infrared luminosity, but we do find that the [N II] 205/CO(6-5) line ratio is correlated with the 60/100 µm Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS) colors. Thus the [N II] 205/CO(6-5) ratio can be used to infer a dust temperature, and hence the intensity of the interstellar radiation field (ISRF). Photodissociation region (PDR) models show that use of [C I] and CO lines in addition to the typical [C II], [O I], and FIR fluxes drive the model solutions to higher densities and lower values of G0. -

1501.01010V1.Pdf

Draft version January 7, 2015 Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 5/2/11 JET-ISM INTERACTION IN THE RADIO GALAXY 3C293: JET-DRIVEN SHOCKS HEAT ISM TO POWER X-RAY AND MOLECULAR H2 EMISSION L. Lanz1, P. M. Ogle1, D. Evans2, P. N. Appleton3, P. Guillard4, B. Emonts5 Draft version January 7, 2015 ABSTRACT We present a 70ks Chandra observation of the radio galaxy 3C 293. This galaxy belongs to the class of molecular hydrogen emission galaxies (MOHEGs) that have very luminous emission from warm molecular hydrogen. In radio galaxies, the molecular gas appears to be heated by jet-driven shocks, but exactly how this mechanism works is still poorly understood. With Chandra, we observe X-ray emission from the jets within the host galaxy and along the 100 kpc radio jets. We model the X-ray spectra of the nucleus, the inner jets, and the X-ray features along the extended radio jets. Both the nucleus and the inner jets show evidence of 107 K shock-heated gas. The kinetic power of the jets is more than sufficient to heat the X-ray emitting gas within the host galaxy. The thermal X-ray and warm H2 luminosities of 3C 293 are similar, indicating similar masses of X-ray hot gas and warm molecular gas. This is consistent with a picture where both derive from a multiphase, shocked interstellar medium (ISM). We find that radio-loud MOHEGs that are not brightest cluster galaxies (BCGs), like 3C 293, typically have LH2 /LX ∼ 1 and MH2 /MX ∼ 1, whereas MOHEGs that are BCGs have LH2 /LX ∼ 0.01 and MH2 /MX ∼ 0.01. -

April Constellations of the Month

April Constellations of the Month Leo Small Scope Objects: Name R.A. Decl. Details M65! A large, bright Sa/Sb spiral galaxy. 7.8 x 1.6 arc minutes, magnitude 10.2. Very 11hr 18.9m +13° 05’ (NGC 3623) high surface brighness showing good detail in medium sized ‘scopes. M66! Another bright Sb galaxy, only 21 arc minutes from M65. Slightly brighter at mag. 11hr 20.2m +12° 59’ (NGC 3627) 9.7, measuring 8.0 x 2.5 arc minutes. M95 An easy SBb barred spiral, 4 x 3 arc minutes in size. Magnitude 10.5, with 10hr 44.0m +11° 42’ a bright central core. The bar and outer ring of material will require larger (NGC 3351) aperature and dark skies. M96 Another bright Sb spiral, about 42 arc minutes east of M95, but larger and 10hr 46.8m +11° 49’ (NGC 3368) brighter. 6 x 4 arc minutes, magnitude 10.1. Located about 48 arc minutes NNE of M96. This small elliptical galaxy measures M105 only 2 x 2.1 arc minutes, but at mag. 10.3 has very high surface brightness. 10hr 47.8m +12° 35’ (NGC 3379) Look for NGC 3384! (110NGC) and NGC 3389 (mag 11.0 and 12.2) which form a small triangle with M105. NGC 3384! 10hr 48.3m +12° 38’ See comment for M105. The brightest galaxy in Leo, this Sb/Sc spiral galaxy shines at mag. 9.5. Look for NGC 2903!! 09hr 32.2m +21° 30’ a hazy patch 11 x 4.7 arc minutes in size 1.5° south of l Leonis. -

The NICMOS Snapshot Survey of Nearby Galaxies

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CERN Document Server The NICMOS snapshot survey of nearby galaxies T. B¨oker1, D. Calzetti, W. Sparks, D. Axon1, L. E. Bergeron, H. Bushouse, L. Colina1, D. Daou, D. Gilmore, S. Holfeltz, J. MacKenty, L. Mazzuca, B. Monroe, J. Najita, K. Noll, A. Nota1,C. Ritchie, A. Schultz, M. Sosey, A. Storrs, A. Suchkov (the STScI NICMOS group) Space Telescope Science Institute, 3700 San Martin Drive, Baltimore, MD 21218, U.S.A. ABSTRACT We present “snapshot” observations with the NearInfrared Camera and MultiObject Spectrometer (NICMOS) on board the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) of 94 nearby galaxies from the Revised Shapley Ames Catalog. Images with 0.200 resolution were obtained in two filters, a broad-band continuum filter (F160W, roughly equivalent to the H-band) and a narrow band filter centered on the Pa α line (F187N or F190N, depending on the galaxy redshift) with the 5100 5100 field of view of the NICMOS camera 3. A first- order continuum subtraction is performed,× and the resulting line maps and integrated Pa α line fluxes are presented. A statistical analysis indicates that the average Pa α surface brightness in the central regions is highest in early-type (Sa-Sb) spirals. Subject headings: infrared:galaxies—infrared:ISM:lines and bands—galaxies:nuclei— galaxies:starburst—galaxies:statistics 1Affiliated with the Astrophysics Division, Space Science Department, European Space Agency 1 1. Introduction with the NIC3 F190N filter. The velocity range was chosen such that the Pa α line falls well inside the NICMOS is a second generation HST instrument, high transmission region of the respective filter, with installed during the HST servicing mission in Febru- only minor corrections ( 5%) needed to account for ary 1997. -

VLBA Detection of Nuclear Compact Emission in the AGN-Driven Molecular Outflow Candidate NGC 1266

VLBA Detection of Nuclear Compact Emission in the AGN-Driven Molecular Outflow Candidate NGC 1266 Kristina Nyland New Mexico Tech 2012 New Mexico Symposium Outflows in Galaxies • Can help regulate star formation and SMBH growth • May be responsible for various empirical scaling relations in galaxies (e.g., Faber-Jackson relation) • Driving mechanisms: • Stellar feedback • Radiation pressure • Stellar winds (young O stars, AGB stars) • Supernovae • AGNs • Quasar mode (radiative) • Radio mode (mechanical/kinetic) Starburst-Driven Molecular Outflows M82 (Walter+02) Arp 220 (Sakamoto+09) • Prototypical SB galaxy • ULIRG • Interacting with M81 • merger remnant • Molecular gas entrained in • (But AGN may play a starburst wind see role, Rangwala+11) 8 7 • Moutflow = 3 x 10 Msun • Moutflow = 5 x 10 Msun • dM/dt = 30 Msun/year • dM/dt = 100 Msun/year • voutflow = 100 km/s • voutflow = 100 km/s HST HST AGN-Driven Molecular Outflows • Outflows of neutral/ionized gas relatively common in AGNs • Molecular outflows potentially powered by AGNs are rare • Much of the evidence is circumstantial • e.g., SDSS statistical analyses of timing of starbursts and AGN activity • Many candidates for direct evidence are high-redshift quasars • local candidates needed! AGN-Driven Molecular Outflows Mrk 231 (Feruglio+10) • Nearest quasar host • Interacting system 8 • Moutflow = 5.8 x 10 Msun • dM/dt = 100-700 Msun/yr • v = 700 km/s outflow Gemini NGC 1266: Local Candidate AGN- driven Molecular Outflow Host? • Morphology: S0 • Environment: Field – no evidence of recent major merger • Distance: 29.9 Mpc • MK = -22.93 DSS • σ* = 79 km/s 6 • MBH: ~3.2 x 10 Msun IRAM 30m CO Emission Figures from Alatalo et al. -

XXXI. Nuclear Radio Emission in Nearby Early-Type Galaxies

MNRAS 458, 2221–2268 (2016) doi:10.1093/mnras/stw391 Advance Access publication 2016 February 24 The ATLAS3D Project – XXXI. Nuclear radio emission in nearby early-type galaxies Kristina Nyland,1,2‹ Lisa M. Young,3 Joan M. Wrobel,4 Marc Sarzi,5 Raffaella Morganti,2,6 Katherine Alatalo,7,8† Leo Blitz,9 Fred´ eric´ Bournaud,10 Martin Bureau,11 Michele Cappellari,11 Alison F. Crocker,12 Roger L. Davies,11 Timothy A. Davis,13 P. T. de Zeeuw,14,15 Pierre-Alain Duc,10 Eric Emsellem,14,16 Sadegh Khochfar,17 Davor Krajnovic,´ 18 Harald Kuntschner,14 Richard M. McDermid,19,20 Thorsten Naab,21 Tom Oosterloo,2,6 22 23 24 Nicholas Scott, Paolo Serra and Anne-Marie Weijmans Downloaded from Affiliations are listed at the end of the paper Accepted 2016 February 17. Received 2016 February 15; in original form 2015 July 3 http://mnras.oxfordjournals.org/ ABSTRACT We present the results of a high-resolution, 5 GHz, Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array study 3D of the nuclear radio emission in a representative subset of the ATLAS survey of early-type galaxies (ETGs). We find that 51 ± 4 per cent of the ETGs in our sample contain nuclear radio emission with luminosities as low as 1018 WHz−1. Most of the nuclear radio sources have compact (25–110 pc) morphologies, although ∼10 per cent display multicomponent core+jet or extended jet/lobe structures. Based on the radio continuum properties, as well as optical emission line diagnostics and the nuclear X-ray properties, we conclude that the at MPI Study of Societies on June 7, 2016 3D majority of the central 5 GHz sources detected in the ATLAS galaxies are associated with the presence of an active galactic nucleus (AGN). -

The Applicability of Far-Infrared Fine-Structure Lines As Star Formation

A&A 568, A62 (2014) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201322489 & c ESO 2014 Astrophysics The applicability of far-infrared fine-structure lines as star formation rate tracers over wide ranges of metallicities and galaxy types? Ilse De Looze1, Diane Cormier2, Vianney Lebouteiller3, Suzanne Madden3, Maarten Baes1, George J. Bendo4, Médéric Boquien5, Alessandro Boselli6, David L. Clements7, Luca Cortese8;9, Asantha Cooray10;11, Maud Galametz8, Frédéric Galliano3, Javier Graciá-Carpio12, Kate Isaak13, Oskar Ł. Karczewski14, Tara J. Parkin15, Eric W. Pellegrini16, Aurélie Rémy-Ruyer3, Luigi Spinoglio17, Matthew W. L. Smith18, and Eckhard Sturm12 1 Sterrenkundig Observatorium, Universiteit Gent, Krijgslaan 281 S9, 9000 Gent, Belgium e-mail: [email protected] 2 Zentrum für Astronomie der Universität Heidelberg, Institut für Theoretische Astrophysik, Albert-Ueberle Str. 2, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany 3 Laboratoire AIM, CEA, Université Paris VII, IRFU/Service d0Astrophysique, Bat. 709, 91191 Gif-sur-Yvette, France 4 UK ALMA Regional Centre Node, Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics, School of Physics and Astronomy, University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PL, UK 5 Institute of Astronomy, University of Cambridge, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0HA, UK 6 Laboratoire d0Astrophysique de Marseille − LAM, Université Aix-Marseille & CNRS, UMR7326, 38 rue F. Joliot-Curie, 13388 Marseille CEDEX 13, France 7 Astrophysics Group, Imperial College, Blackett Laboratory, Prince Consort Road, London SW7 2AZ, UK 8 European Southern Observatory, Karl -

¼¼Çwªâðw¦¹Á¼ºëw£Àêëw ˆ†ˆ€ «ÆÊ¿Àäàww«¸ÂÀ ‰‡‡Œ†ˆ‰†‰Œ

¼¼ÇwªÂÐw¦¹Á¼ºËw£ÀÊËw II - C ll r l 400 e e l G C k i 200 r he Dec. P.A. w R.A. Size Size Chart N a he ss d l Object Type Con. Mag. Class t NGC Description l AS o o sc e s r ( h m ) max min No. C a ( ' ) ( ) sc R AAS e r e M C T e B H H NGC 7192 GALXY IND 22 06.8 -64 19 11.2 1.9 m 1.8 m Elliptical pB,S,R,pmbM 134 NGC 7219 GALXY TUC 22 13.1 -64 51 12.5 1.7 m 1 m 27 SBa pB,S,R,2st nr 134 NGC 7329 GALXY TUC 22 40.4 -66 29 11.3 3.7 m 2.7 m 107 SBbc Ring pB,pS,mE90 134 NGC 7417 GALXY TUC 22 57.8 -65 02 12.3 1.9 m 1.3 m 2 SBab Ring pB,cS,R,gpmbM 134 NGC 7637 GALXY OCT 23 26.5 -81 55 12.5 2.1 m 1.9 m Sc vF,pL,R,vlbM,* nr 134 «ÆÊ¿ÀÄÀww«¸ÂÀ ¼¼ÇwªÂÐw¦¹Á¼ºËw£ÀÊËw II - C ll r l 400 e e l G C k i 200 r he Dec. P.A. w R.A. Size Size Chart N a he ss d l Object Type Con. Mag. Class t NGC Description l AS o o sc e s r ( h m ) max min No. C a ( ' ) ( ) sc R AAS e r e M C T e B H H Mel 227 OPNCL OCT 20 12.1 -79 19 5.3 50.0 m II 2 p 135 NGC 6872 GALXY PAV 20 17.0 -70 46 11.8 6.3 m 2.2 m 66 SBb/P F,pS,lE,glbM,1st of 4 135 NGC 6876 GALXY PAV 20 18.3 -70 52 11.1 3 m 2.6 m 80 E3 pB,S,R,eS* sf,2nd of 4 135 NGC 6877 GALXY PAV 20 18.6 -70 51 12.2 2 m 1 m 169 E6 vF,vS,R,3rd of 4 135 NGC 6880 GALXY PAV 20 19.5 -70 52 12.2 2.1 m 1.3 m 35 SBO-a F,S,R,r,vS* att,4 of 4 135 NGC 6920 GALXY OCT 20 44.0 -80 00 12.5 1.8 m 1.5 m SO pB,cS,R,psmbM 135 NGC 6943 GALXY PAV 20 44.6 -68 45 11.4 4 m 2.2 m 130 SBc pF,L,mE,vglbM vS* 135 IC 5052 GALXY PAV 20 52.1 -69 12 11.2 5.9 m 0.9 m 143 SBcd F,L,eE 140 deg 135 NGC 7020 GALXY PAV 21 11.3 -64 02 11.8 3.5 m 1.6 m 165 SBO-a Ring pB,cS,lE,pgbM 135 NGC 7083 GALXY IND 21 35.7 -63 54 11.2 3.6 m 2.1 m 5 Sbc pF,cL,vlE,vgpmbM,r 135 NGC 7096 GALXY IND 21 41.3 -63 55 11.9 1.8 m 1.6 m 130 Sa vF,S,R,vS** nf 135 NGC 7098 GALXY OCT 21 44.3 -75 07 11.3 4 m 2.6 m 74 SB Ring pF,R,g,psmbM,am st 135 NGC 7095 GALXY OCT 21 52.4 -81 32 11.5 4 m 3.3 m Sc F,pL,R,vglbM,*13 inv 135 «ÆÊ¿ÀÄÀww«¸ÂÀ ¼¼ÇwªÂÐw¦¹Á¼ºËw£ÀÊËw II - C ll r l 400 e e l G C k i 200 r he Dec. -

The Low-Metallicity Picture A

Linking dust emission to fundamental properties in galaxies: the low-metallicity picture A. Rémy-Ruyer, S. C. Madden, F. Galliano, V. Lebouteiller, M. Baes, G. J. Bendo, A. Boselli, L. Ciesla, D. Cormier, A. Cooray, et al. To cite this version: A. Rémy-Ruyer, S. C. Madden, F. Galliano, V. Lebouteiller, M. Baes, et al.. Linking dust emission to fundamental properties in galaxies: the low-metallicity picture. Astronomy and Astrophysics - A&A, EDP Sciences, 2015, 582, pp.A121. 10.1051/0004-6361/201526067. cea-01383748 HAL Id: cea-01383748 https://hal-cea.archives-ouvertes.fr/cea-01383748 Submitted on 19 Oct 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. A&A 582, A121 (2015) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201526067 & c ESO 2015 Astrophysics Linking dust emission to fundamental properties in galaxies: the low-metallicity picture? A. Rémy-Ruyer1;2, S. C. Madden2, F. Galliano2, V. Lebouteiller2, M. Baes3, G. J. Bendo4, A. Boselli5, L. Ciesla6, D. Cormier7, A. Cooray8, L. Cortese9, I. De Looze3;10, V. Doublier-Pritchard11, M. Galametz12, A. P. Jones1, O. Ł. Karczewski13, N. Lu14, and L. Spinoglio15 1 Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale, CNRS, UMR 8617, 91405 Orsay, France e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] 2 Laboratoire AIM, CEA/IRFU/Service d’Astrophysique, Université Paris Diderot, Bât. -

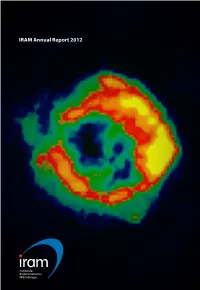

IRAM Annual Report 2012

IRAM IRAM Annual Report 2012 Institut de Radioastronomie Millimétrique 30-meter diameter telescope, Pico Veleta 6 x 15-meter interferometer, Plateau de Bure The Institut de Radioastronomie Millimétrique (IRAM) is a multi-national scientific institute covering all aspects of radio astronomy at millimeter wavelengths: the operation of two high-altitude observatories – a 30-meter diameter telescope on Pico Veleta in the Sierra Nevada (southern Spain), and an interferometer of six 15 meter diameter telescopes on the Plateau de Bure in the French Alps – the development of telescopes and instrumentation, radio astronomical observations and their interpretation. IRAM was founded in 1979 by two national research organizations: the CNRS and the Max-Planck-Gesellschaft – the Spanish Instituto Geográfico IRAM Addresses: Nacional, initially an associate member, became a full member in 1990. Institut de Radioastronomie The technical and scientific staff of IRAM develops instrumentation and Millimétrique 300 rue de la piscine, software for the specific needs of millimeter radioastronomy and for the Saint-Martin d’Hères benefit of the astronomical community. IRAM’s laboratories also supply F-38406 France Tel: +33 [0]4 76 82 49 00 devices to several European partners, including for the ALMA project. Fax: +33 [0]4 76 51 59 38 [email protected] www.iram.fr IRAM’s scientists conduct forefront research in several domains of astrophysics, from nearby star-forming regions to objects at cosmological Observatoire du Plateau de Bure distances. Saint-Etienne-en-Dévoluy -

![Arxiv:1007.4547V2 [Astro-Ph.CO]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9148/arxiv-1007-4547v2-astro-ph-co-1419148.webp)

Arxiv:1007.4547V2 [Astro-Ph.CO]

ApJS, in press Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 11/10/09 OPTICAL SPECTROSCOPY AND NEBULAR OXYGEN ABUNDANCES OF THE SPITZER/SINGS GALAXIES John Moustakas1, Robert C. Kennicutt, Jr.2,3, Christy A. Tremonti4, Daniel A. Dale5, John-David T. Smith6, Daniela Calzetti7 ApJS, in press ABSTRACT We present intermediate-resolution optical spectrophotometry of 65 galaxies obtained in support of the Spitzer Infrared Nearby Galaxies Survey (SINGS). For each galaxy we obtain a nuclear, circumnu- clear, and semi-integrated optical spectrum designed to coincide spatially with mid- and far-infrared spectroscopy from the Spitzer Space Telescope. We make the reduced, spectrophotometrically cali- brated one-dimensional spectra, as well as measurements of the fluxes and equivalent widths of the strong nebular emission lines, publically available. We use optical emission-line ratios measured on all three spatial scales to classify the sample into star-forming, active galactic nuclei (AGN), and galaxies with a mixture of star formation and nuclear activity. We find that the relative fraction of the sample classified as star-forming versus AGN is a strong function of the integrated light enclosed by the spec- troscopic aperture. We supplement our observations with a large database of nebular emission-line measurements of individual H ii regions in the SINGS galaxies culled from the literature. We use these ancillary data to conduct a detailed analysis of the radial abundance gradients and average H ii- region abundances of a large fraction of the sample. We combine these results with our new integrated spectra to estimate the central and characteristic (globally-averaged) gas-phase oxygen abundances of all 75 SINGS galaxies. -

Astronomy Magazine 2011 Index Subject Index

Astronomy Magazine 2011 Index Subject Index A AAVSO (American Association of Variable Star Observers), 6:18, 44–47, 7:58, 10:11 Abell 35 (Sharpless 2-313) (planetary nebula), 10:70 Abell 85 (supernova remnant), 8:70 Abell 1656 (Coma galaxy cluster), 11:56 Abell 1689 (galaxy cluster), 3:23 Abell 2218 (galaxy cluster), 11:68 Abell 2744 (Pandora's Cluster) (galaxy cluster), 10:20 Abell catalog planetary nebulae, 6:50–53 Acheron Fossae (feature on Mars), 11:36 Adirondack Astronomy Retreat, 5:16 Adobe Photoshop software, 6:64 AKATSUKI orbiter, 4:19 AL (Astronomical League), 7:17, 8:50–51 albedo, 8:12 Alexhelios (moon of 216 Kleopatra), 6:18 Altair (star), 9:15 amateur astronomy change in construction of portable telescopes, 1:70–73 discovery of asteroids, 12:56–60 ten tips for, 1:68–69 American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO), 6:18, 44–47, 7:58, 10:11 American Astronomical Society decadal survey recommendations, 7:16 Lancelot M. Berkeley-New York Community Trust Prize for Meritorious Work in Astronomy, 3:19 Andromeda Galaxy (M31) image of, 11:26 stellar disks, 6:19 Antarctica, astronomical research in, 10:44–48 Antennae galaxies (NGC 4038 and NGC 4039), 11:32, 56 antimatter, 8:24–29 Antu Telescope, 11:37 APM 08279+5255 (quasar), 11:18 arcminutes, 10:51 arcseconds, 10:51 Arp 147 (galaxy pair), 6:19 Arp 188 (Tadpole Galaxy), 11:30 Arp 273 (galaxy pair), 11:65 Arp 299 (NGC 3690) (galaxy pair), 10:55–57 ARTEMIS spacecraft, 11:17 asteroid belt, origin of, 8:55 asteroids See also names of specific asteroids amateur discovery of, 12:62–63