OHADA on the Ground: Harmonizing Business Laws in Three Dimensions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Invest in Côte D'ivoire a Business Guide for Africa's Fastest-Growing

Invest in Côte d’Ivoire A business guide for Africa’s fastest-growing economy March 2017 Proposal title goes here | Section title goes here “Côte d’Ivoire is Africa’s fastest-growing economy. The fast pace of growth is due to a strong macroeconomic environment, a solid position in international markets and a large amount of significant natural resources.” 03 Invest in Côte d’Ivoire | Table of contents Table of contents Executive summary 3 Country overview 5 Côte d’Ivoire’s economy 6 Business environment 13 Investment opportunities 21 Challenges and risks 27 References 28 Appendix 29 Contacts 35 2 Invest in Côte d’Ivoire | Executive summary Executive summary Located in the inter-tropical coastal zone sustainable growth. Two development Consequently, Côte d’Ivoire has improved of West Africa, the Republic of Côte d’Ivoire plans have been implemented in Côte its rankings in the World Bank’s annual has a population of 22.7 million inhabitants, d’Ivoire: the National Development Plan Ease of Doing Business index, moving 42.5% of whom are under the age of 14. (NDP) 2012-15 to lay the foundations for an from 177th position in the 2014 report Yamoussoukro is the political capital, emerging economy; and the NDP 2016-20 (out of 189 countries) to the 142nd while Abidjan is the economic hub of the to structurally transform the country into position in 2017 (out of 190 countries). country. The country is a member of the an industrialising nation. The 2014 and 2015 reports ranked Côte West African Economic Monetary Union d’Ivoire among the 10 best reformers in (WAEMU), an eight country customs and With a total investment of 3trn CFAF, the world. -

A Brief Overview of Mining in Senegal by Alban Dorin and Lara Welsh

Article A brief overview of mining in Senegal By Alban Dorin and Lara Welsh Overview of Senegalese legal OHADA provides for a uniform system of system business law directly applicable in its Member States through “Uniform Acts” which have Senegal is a civil law jurisdiction, meaning that been largely inspired by French law. These the core principles of law are codified and serve Uniform Acts cover matters such as corporate as the primary source of law. The Constitution law, security, insolvency, arbitration and of Senegal, adopted by constitutional refer- recognition of foreign courts’ decisions. Alban Dorin enda on 7 January 2001, is the fourth Counsel, Paris Senegal is part of WAEMU (or UEMOA in constitution of the country (after those of 1959, E: [email protected] French) - The West African Economic and 1960 and 1963). As with most Franco-African T: +33 1 53 53 18 51 countries, the Constitution of Senegal is heavily Monetary Union – which is an organisation of based on the 1958 French Constitution, 8 West African states established to promote considered as being the ‘Mother Constitution’. economic integration among countries that share the CFA franc as a common currency. Whereas in a common law legal system (such as The CFA Franc (FCFA) is linked to the Euro at a England and Wales) judicial cases are regarded fixed rate of 655,957 FCFA to 1 Euro. as the most important source of law (giving judges an active role in developing rules), in It is also part of ECOWAS - The Economic civil-law systems codes and statutes are Community of West African States - which is a Lara Welsh designed to cover all eventualities and judges regional group of 15 West African nations Senior Associate, London have a more limited role - to apply the law to the created to promote economic integration E: [email protected] case in hand. -

Guinea Bissau IFRS Profile

IFRS APPLICATION AROUND THE WORLD JURISDICTIONAL PROFILE: Guinea Bissau Disclaimer: The information in this Profile is for general guidance only and may change from time to time. You should not act on the information in this Profile, and you should obtain specific professional advice to help you in making any decisions or in taking any action. If you believe that the information has changed or is incorrect, please contact us at [email protected]. This Profile provides information about the application of IFRS Standards in Guinea Bissau. IFRS Standards are developed and issued in the public interest by the International Accounting Standards Board (the Board). The Board is the standard-setting body of the IFRS® Foundation, an independent, private sector, not-for-profit organisation. This Profile has been prepared by the IFRS Foundation based on information from various sources. The starting point was the answers provided by standard-setting and other relevant bodies in response to surveys that the Foundation conducted on the application of IFRS Standards around the world. The Foundation drafted the profile and invited the respondents to the survey and others (including regulators and international audit firms) to review the drafts, and their comments are reflected. The purpose of the IFRS Foundation’s Jurisdictional Profiles is to illustrate the extent of implementation of IFRS Standards across the globe only. The Profiles do not reflect the intellectual property licensing status of IFRS Standards within any given jurisdiction. The IFRS Standards are protected by copyright and are subject to different licensing arrangements according to jurisdiction. For further information, please contact [email protected]. -

Equatorial Guinea

Doing Business 2020 Equatorial Guinea Economy Profile Equatorial Guinea Page 1 Doing Business 2020 Equatorial Guinea Economy Profile of Equatorial Guinea Doing Business 2020 Indicators (in order of appearance in the document) Starting a business Procedures, time, cost and paid-in minimum capital to start a limited liability company Dealing with construction permits Procedures, time and cost to complete all formalities to build a warehouse and the quality control and safety mechanisms in the construction permitting system Getting electricity Procedures, time and cost to get connected to the electrical grid, and the reliability of the electricity supply and the transparency of tariffs Registering property Procedures, time and cost to transfer a property and the quality of the land administration system Getting credit Movable collateral laws and credit information systems Protecting minority investors Minority shareholders’ rights in related-party transactions and in corporate governance Paying taxes Payments, time, total tax and contribution rate for a firm to comply with all tax regulations as well as postfiling processes Trading across borders Time and cost to export the product of comparative advantage and import auto parts Enforcing contracts Time and cost to resolve a commercial dispute and the quality of judicial processes Resolving insolvency Time, cost, outcome and recovery rate for a commercial insolvency and the strength of the legal framework for insolvency Employing workers Flexibility in employment regulation and redundancy cost Page 2 Doing Business 2020 Equatorial Guinea About Doing Business The Doing Business project provides objective measures of business regulations and their enforcement across 190 economies and selected cities at the subnational and regional level. -

Creating Markets in Senegal

CREATING MARKETS SENEGAL IN CREATING A COUNTRY PRIVATE SECTOR DIAGNOSTIC SECTOR PRIVATE COUNTRY A A COUNTRY PRIVATE SECTOR DIAGNOSTIC CREATING MARKETS IN SENEGAL Sustaining growth in an uncertain environment APRIL 2020 About IFC IFC—a sister organization of the World Bank and member of the World Bank Group—is the largest global development institution focused on the private sector in emerging markets. We work with more than 2,000 businesses worldwide, using our capital, expertise, and influence to create markets and opportunities in the toughest areas of the world. In fiscal year 2018, we delivered more than $23 billion in long-term financing for developing countries, leveraging the power of the private sector to end extreme poverty and boost shared prosperity. For more information, visit www.ifc.org © International Finance Corporation 2020. All rights reserved. 2121 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20433 www.ifc.org The material in this report was prepared in consultation with government officials and the private sector in Senegal and is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. IFC does not guarantee the accuracy, reliability or completeness of the content included in this work, or for the conclusions or judgments described herein, and accepts no responsibility or liability for any omissions or errors (including, without limitation, typographical errors and technical errors) in the content whatsoever or for reliance thereon. The findings, interpretations, views, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of the International Finance Corporation or of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (the World Bank) or the governments they represent. -

Reforms to OHADA Commercial

Legal & Regulatory Bulletin Reforms to OHADA Commercial Law: Towards a More Attractive Legal Framework for Private Equity By Sydney Domoraud-Operi and Anthony Riley, Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe LLP Introduction organizing Collective Proceedings for Clearing Debts; Arbitration; and organizing and harmonizing Undertakings The Organisation pour l'Harmonisation en Afrique du Droit Accountings Systems; Contracts for the Carriage of Goods des Affaires ("OHADA"), which translates into English as by Road; and Cooperative Companies. the "Organisation for the Harmonization of Business Law in Africa" is an exclusively business-related legal framework Today, OHADA continues to extend the scope of its legal that was created on 17 October 1993 in Port Louis, Mauritius. reforms to better suit the needs of its Member States and their investors. Having previously reformed the Uniform Acts Initially established pursuant to a treaty adopted among 14 for Security Interests, Cooperative Companies and General Member States (the "OHADA Treaty"), OHADA membership Commercial Law in December 2010, OHADA adopted on has grown to 17 since 1993.1 OHADA enacts, among other 30 January 2014 substantial amendments to its core cor- provisions, Uniform Acts that have direct effect and super- porations law, the Uniform Act relating to Commercial sede contradictory national laws, subject to any transitional Companies and Economic Interest Groups (known as the provisions stipulated by the Uniform Acts. The OHADA "AUSCGIE"), with almost two hundred new articles and some Treaty also created a supranational supreme court with four hundred revised provisions. jurisdiction over the areas of law covered by the Uniform Acts (the Cour Commune de Justice et d'Arbitrage or CCJA), The new AUSCGIE will come into force on 5 May 2014. -

The Ohada Treaty in the Context of International Insolvency Law Developments

THE OHADA TREATY IN THE CONTEXT OF INTERNATIONAL INSOLVENCY LAW DEVELOPMENTS Joanna A. Owusu•Ansah Institute for Law and Finance, University of Frankfurt, Germany. [email protected] April 2004 Paper presented within the LL.M in Finance course ‘International Insolvency Law’, led by Professor Dr. Bob Wessels Institute for Law and Finance, Johann Wolfgang Goethe University, Frankfurt, Germany. © International Insolvency Institute - www.iiiglobal.org TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Background to OHADA 1 1.2 Overview of the OHADA Treaty 2 2. The Uniform Act Organising Collective Proceedings for 2 the Wiping off Debts 2.1 The Uniform Act and the EU Insolvency Regulation 4 2.2 Case study: Air Afrique 6 2.3 The Uniform Act and the UNCITRAL Model Law 7 Conclusion 8 Bibliography © International Insolvency Institute - www.iiiglobal.org 1. INTRODUCTION It is an accepted fact that with the globalization of world economies the constant flow of people, products and wealth across the globe has become indispensable and this has led to the opening up of continents and the fading out of strict trade barriers. With this development come the attendant effect of trade failures and its consequences on various economies and the need to lay down a standard acceptable at least between trading partners to protect the interests of their investors in such situations. It is in the light of the above that OHADA, which stands for ‘Organisation pour l’Harmonisation en Afrique du Droit des Affaires’, which translates into English as ‘Organisation for the Harmonisation of Business Law in Africa’ came into being. -

Côte D'ivoire

IFRS APPLICATION AROUND THE WORLD JURISDICTIONAL PROFILE: Côte d’Ivoire Disclaimer: The information in this Profile is for general guidance only and may change from time to time. You should not act on the information in this Profile, and you should obtain specific professional advice to help you in making any decisions or in taking any action. If you believe that the information has changed or is incorrect, please contact us at [email protected]. This Profile provides information about the application of IFRS Standards in Côte d'Ivoire. IFRS Standards are developed and issued in the public interest by the International Accounting Standards Board (the Board). The Board is the standard-setting body of the IFRS® Foundation, an independent, private sector, not-for-profit organisation. This Profile has been prepared by the IFRS Foundation based on information from various sources. The starting point was the answers provided by standard-setting and other relevant bodies in response to surveys that the Foundation conducted on the application of IFRS Standards around the world. The Foundation drafted the profile and invited the respondents to the survey and others (including regulators and international audit firms) to review the drafts, and their comments are reflected. The purpose of the IFRS Foundation’s Jurisdictional Profiles is to illustrate the extent of implementation of IFRS Standards across the globe only. The Profiles do not reflect the intellectual property licensing status of IFRS Standards within any given jurisdiction. The IFRS Standards are protected by copyright and are subject to different licensing arrangements according to jurisdiction. For further information, please contact [email protected]. -

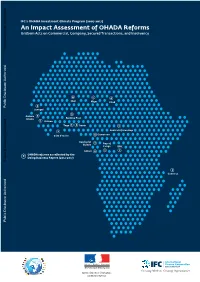

IFC and OHADA

1 IFC's OHADA Investment Climate Program (2007-2017) An Impact Assessment of OHADA Reforms Uniform Acts on Commercial, Company, Secured Transactions, and Insolvency Public Disclosure Authorized 4 5 4 Mali Niger Chad 6 Public Disclosure Authorized Senegal 5 Guinea 4 Bissau Burkina Faso 5 Guinea Togo 4 5 Benin 4 5 Central African Rep Cameroon Cóte d’Ivoire 4 Equitorial 3 Rep of Guinea Congo DRC Gabon 4 3 5 # OHADA reforms as reflected by the Doing Business Report (2012-2017) Public Disclosure Authorized 5 Comoros Public Disclosure Authorized MINISTÈRE DE L’ÉCONOMIE ET DES FINANCES 2 3 © 2018 International Finance Corporation / OHADA Permanent Secretariat 2121 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, D.C. 20433 Internet: www.ifc.org Some rights reserved This is a co-publication of the International Finance Corporation and the OHADA Permanent Secretariat. This work is a product of the staff of the International Finance Corporation, the OHADA Permanent Secretariat, ECOPA, and ECONOMISTI ASSOCIATI. Note that the International Finance Corporation and the OHADA Permanent Secretariat do not necessarily own each component of the content included in the work. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Finance Corporation, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent, nor does it represent those of the OHADA Permanent Secretariat. The International Finance Corporation and the OHADA Permanent Secretariat do not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of the International Finance Corporation or the OHADA Permanent Secretariat concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. -

L'entreprenant En Droit Ohada

L’entreprenant en droit OHADA Danielle Beatrice Ongono Bikoe To cite this version: Danielle Beatrice Ongono Bikoe. L’entreprenant en droit OHADA. Droit. Université Panthéon- Sorbonne - Paris I, 2020. Français. NNT : 2020PA01D003. tel-02943078 HAL Id: tel-02943078 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02943078 Submitted on 18 Sep 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. L'ENTREPRENANT EN DROIT OHADA THESE EN VUE DE L’OBTENTION D’UN DOCTORAT EN DROIT PRIVE Présentée et soutenue par : Danielle Béatrice ONGONO BIKOE Directeur de thèse : François-Xavier LUCAS Professeur à l’Ecole de droit de La Sorbonne (Université de Paris 1) Membres du jury M. Mamadou Ismaila KONATE Avocat à la Cour, Barreaux du Mali et de Paris M. Sylvain Sorel KUATE TAMEGHE Maître de conférences à l’université de Yaoundé 2 Soa, HDR M. François-Xavier LUCAS Professeur à l’Ecole de droit de La Sorbonne (Université de Paris 1) M. Didier PORACCHIA Professeur à l’Ecole de droit de La Sorbonne (Université de Paris 1) M. Pascal RUBELLIN Maître de conférences à la faculté de droit de Poitiers, HDR DEDICACE A Emmanuel, le Fidèle et Véritable. -

Doing Business in the Central African Republic

doing business in the Central African Republic country profile international treaties and memberships government Executive: The president is chief of state and the prime minister is the international African Continental Free Trade Area Agreement structure head of government. The president is elected by universal direct suffrage and regional African Development Bank for a period of five years and is eligible for a second term. Cabinet is organisations African Union appointed by the president. and customs Development Bank of Central African States (Banque de Développement Legislative: Central African Republic (“CAR”) has a unicameral National unions des Etats de l'Afrique Centrale (“BDEAC”)) Assembly. Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa (Communauté Judicial: The highest courts are the Supreme Court and the Constitutional Économique et Monétaire de l’Afrique Centrale (“CEMAC“)) Court. The subordinate courts are high courts and magistrate courts. Group of 77 Next presidential elections: December 2020. International Fund for Agricultural Development International Monetary Fund economic Nominal GDP (US Billions): 2.49 Organisation internationale de la Francophonie data GDP per capita (USD): 471.94 Organisation of African, Caribbean and Pacific States Inflation rate (% change): 2.56 Organization for the Harmonization of Business Law in Africa (“OHADA”) Government revenue (% of GDP): 18.95 United Nations Government gross debt (% of GDP): 39.23 World Bank Group *Source: IMF (September 2020) CAR receives preferential treatment under the following agreements: http://ptadb.wto.org/Country.aspx?code=140 The Backbone of CAR’s economy is subsistence agriculture, together with bilateral CAR has bilateral investment treaties in force with Germany and forestry and mining. investment Switzerland. -

Ivory-Coast-Fiscal-Guide-2015-2016

0 | Ivory Coast Fiscal Guide 2015/2016 Tax kpmg.com 1 | IvoryNigeria Coast Fiscal Fiscal Guide Guide 2013/2014 2015/2016 INTRODUCTION Ivory Coast Fiscal Guide 2015/2016 | 2 Business income The income tax in Ivory Coast, which is imposed under the General Tax Code (GTC) and applies to both resident and non-resident companies, is divided into a series of scheduler taxes, with each particular category of income (or schedule) being computed and taxed according to different rules. The main categories comprise industrial and commercial profits, non-commercial profits, wages and salaries, income from transferable securities (i.e. dividends, interest), income from land and agricultural income. The standard corporate tax rate is 25%. Companies are also subject to the minimum lump-sum tax (even if it is a loss making company). Rates Resident companies Corporation tax - Resident company 25% - Resident telecommunication company 30%* Non-commercial income 25% Capital gains Part of business income Dividends 2%,10%, 12%,15% Interest Between 1% and 18% Royalties 20% Management fees 20% Withholding tax (local transactions) 7,5% Tax on salaries for local employees 2,8% Tax on salaries for expatriate employees 12% *From 1st January 2014 Resident individuals Progressive: Personal Income tax between 9.5% and 37.5%. 20% for business income Non-commercial income 20% Capital gains Part of personal income Dividends 2%,10%,15% Interest 1%,10%,13,5%,16,5%, 18% Employment income 1.5% National contribution Between 1,5% and 10% Ivory Coast Fiscal Guide 2015/2016 | 3 Non-residents Income tax (individuals) 20% Corporation tax (companies) 25%, 30% Capital gains (individuals and companies) Part of personal/business income Dividends 15%** Interest 18%** Non-commercial income 25%** Management or consultancy fees 20%** Leasing equipment from non-residents 20%** *Final tax withheld at source (rate may vary based on the tax treaty) Capital gains are not taxed separately as such, but are included in ordinary income and subject to corporate income tax.