Girl With!A Camera

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT of INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION in Re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMEN

USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 1 of 354 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION ) Case No. 3:05-MD-527 RLM In re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE ) (MDL 1700) SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMENT ) PRACTICES LITIGATION ) ) ) THIS DOCUMENT RELATES TO: ) ) Carlene Craig, et. al. v. FedEx Case No. 3:05-cv-530 RLM ) Ground Package Systems, Inc., ) ) PROPOSED FINAL APPROVAL ORDER This matter came before the Court for hearing on March 11, 2019, to consider final approval of the proposed ERISA Class Action Settlement reached by and between Plaintiffs Leo Rittenhouse, Jeff Bramlage, Lawrence Liable, Kent Whistler, Mike Moore, Keith Berry, Matthew Cook, Heidi Law, Sylvia O’Brien, Neal Bergkamp, and Dominic Lupo1 (collectively, “the Named Plaintiffs”), on behalf of themselves and the Certified Class, and Defendant FedEx Ground Package System, Inc. (“FXG”) (collectively, “the Parties”), the terms of which Settlement are set forth in the Class Action Settlement Agreement (the “Settlement Agreement”) attached as Exhibit A to the Joint Declaration of Co-Lead Counsel in support of Preliminary Approval of the Kansas Class Action 1 Carlene Craig withdrew as a Named Plaintiff on November 29, 2006. See MDL Doc. No. 409. Named Plaintiffs Ronald Perry and Alan Pacheco are not movants for final approval and filed an objection [MDL Doc. Nos. 3251/3261]. USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 2 of 354 Settlement [MDL Doc. No. 3154-1]. Also before the Court is ERISA Plaintiffs’ Unopposed Motion for Attorney’s Fees and for Payment of Service Awards to the Named Plaintiffs, filed with the Court on October 19, 2018 [MDL Doc. -

THE INTERNATIONAL MAGAZINE of the AVEDIS ZILDJIAN COMPANY Welcome To

ZL326 THE INTERNATIONAL MAGAZINE OF THE AVEDIS ZILDJIAN COMPANY welcome to Z Time2011 edition issue 33 2011 Z Time Page two News & Events Page six Greatest Cymbal of All Time Page ten Legends Page fourteen Gen 16 Craigie Zildjian Page sixteen On the Road Page twenty Moving Forward Product Info Intro There are so many exciting new things going on here at Zildjian that I couldn’t wait to share this year’s Z-Time with you. 2011 represents our breakthrough into the digital Page twenty-one music making realm. Our new Gen16 product line is the result of our effort to bring our Cast Cymbals knowledge of cymbals and their sounds to the modern digital environment. You can learn more about this initiative on pages 14 and 15 or at our new website www.zildjian.com. Page fifty-five Sheet Cymbals Whether your music making is acoustic, digital, or both, our desire is to be there no matter where your music takes you. I sincerely hope you enjoy the journey. Page sixty-one Drumsticks Best regards, Page sixty-five Gear Page sixty-eight Scrapbook Craigie & Debbie Zildjian Contributing photographers: Sayre Berman Hadas Naoju Nakamura John Stephens cover artist: Volker Beushausen Heinz Kronberger Kacper Diana Nitschke Levi Tecofsky Dominic Howard - Joris Bulckens Kaminski Jimmy Katz Mario Pires Melissa Terry Muse Tina Korhonen Bernard Rosenberg Andreas Ulvo James Cumpsty photo: Calum Doris Scott Legato Tao Ruspoli JonVanDaal Richard Ecclestone Robert Downs Hyejin, Lee Bianca Scharroo Neil Zlozower Sergey Dudin H.J Lee Ronny Sequeira Ludwig Drums graphic designer: M.v.d. -

UNIVERSAL MUSIC • Rammstein – Videos 1995 – 2012 (DVD) • The

Rammstein – Videos 1995 – 2012 (DVD) The Rolling Stones – Grrr (Album Vinyl Box) Insane Clown Posse – Insane Clown Posse & Twiztid's American Psycho Tour Documentary (DVD) New Releases From Classics And Jazz Inside!! And more… UNI13-03 “Our assets on-line” UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Ave., Suite 1, Willowdale, Ontario M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718.4000 Artwork shown may not be final UNIVERSAL MUSIC CANADA NEW RELEASE Artist/Title: Hollywood Undead – Notes From The Underground Bar Code: Cat. #: B001797702 Price Code: SP Order Due: December 20, 2012 Release Date: January 8, 2013 File: Hip Hop /Rock Genre Code: 34/37 Box Lot: 25 SHORT SELL CYCLE Key Tracks: We Are KEY POINTS: 14 BRAND NEW TRACKS Hollywood Undead have sold over 83,000 albums in Canada HEAVY outdoor, radio and online campaign First single “We Are” video is expected mid December 2013 Tour in the works 2.8 million Facebook friends and 166,000 Twitter followers Also Available American Tragedy (2011) ‐ B001527502 Swan Song (2008) ‐ B001133102 INTERNAL USE Label Name: Territory: Choose Release Type: Choose For additional artist information please contact JP Boucher at 416‐718‐4113 or [email protected]. UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Avenue, Suite 1, Toronto, ON M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718‐4000 Fax: (416) 718‐4218 UNIVERSAL MUSIC CANADA NEW RELEASE Artist/Title: Black Veil Brides / Wretched And Divine: The Story Of Bar Code: The Wild Ones (Regular CD) Cat. #: B001781702 Price Code: SP 02537 22095 Order Due: Dec. 20, 2012 Release Date: Jan. 8, 2013 6 3 File: Rock Genre Code: 37 Box Lot: 25 Short Sell Cycle Key Tracks: Artist/Title: Black Veil Brides / Wretched And Divine: The Story Of Bar Code: The Wild Ones (Deluxe CD/DVD) Cat. -

The Singing Guitar

August 2011 | No. 112 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Mike Stern The Singing Guitar Billy Martin • JD Allen • SoLyd Records • Event Calendar Part of what has kept jazz vital over the past several decades despite its commercial decline is the constant influx of new talent and ideas. Jazz is one of the last renewable resources the country and the world has left. Each graduating class of New York@Night musicians, each child who attends an outdoor festival (what’s cuter than a toddler 4 gyrating to “Giant Steps”?), each parent who plays an album for their progeny is Interview: Billy Martin another bulwark against the prematurely-declared demise of jazz. And each generation molds the music to their own image, making it far more than just a 6 by Anders Griffen dusty museum piece. Artist Feature: JD Allen Our features this month are just three examples of dozens, if not hundreds, of individuals who have contributed a swatch to the ever-expanding quilt of jazz. by Martin Longley 7 Guitarist Mike Stern (On The Cover) has fused the innovations of his heroes Miles On The Cover: Mike Stern Davis and Jimi Hendrix. He plays at his home away from home 55Bar several by Laurel Gross times this month. Drummer Billy Martin (Interview) is best known as one-third of 9 Medeski Martin and Wood, themselves a fusion of many styles, but has also Encore: Lest We Forget: worked with many different artists and advanced the language of modern 10 percussion. He will be at the Whitney Museum four times this month as part of Dickie Landry Ray Bryant different groups, including MMW. -

An Alabama School Girl in Paris 1842-1844

An Alabama School Girl in Paris 1842-1844 the letters of Mary Fenwick Lewis and her family Nancyt/ M. Rohr_____ _ An Alabama School Girl in Paris, 1842-1844 The Letters of Mary Fenwick Lewis and Her Family Edited by Nancy M. Rohr An Alabama School Girl In Paris N a n c y M. Ro h r Copyright Q 2001 by Nancy M. Rohr All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission of the editor. ISPN: 0-9707368-0-0 Silver Threads Publishing 10012 Louis Dr. Huntsville, AL 35803 Second Edition 2006 Printed by Boaz Printing, Boaz, Alabama CONTENTS Preface...................................................................................................................1 EditingTechniques...........................................................................................5 The Families.......................................................................................................7 List of Illustrations........................................................................................10 I The Lewis Family Before the Letters................................................. 11 You Are Related to the Brave and Good II The Calhoun Family Before the Letters......................................... 20 These Sums will Furnish Ample Means Apples O f Gold in Pictures of Silver........................................26 III The Letters - 1842................................................................................. 28 IV The Letters - 1843................................................................................ -

Het Verhaal Van De 340 Songs Inhoud

Philippe Margotin en Jean-Michel Guesdon Rollingthe Stones compleet HET VERHAAL VAN DE 340 SONGS INHOUD 6 _ Voorwoord 8 _ De geboorte van een band 13 _ Ian Stewart, de zesde Stone 14 _ Come On / I Want To Be Loved 18 _ Andrew Loog Oldham, uitvinder van The Rolling Stones 20 _ I Wanna Be Your Man / Stoned EP DATUM UITGEBRACHT ALBUM Verenigd Koninkrijk : Down The Road Apiece ALBUM DATUM UITGEBRACHT 10 januari 1964 EP Everybody Needs Somebody To Love Under The Boardwalk DATUM UITGEBRACHT Verenigd Koninkrijk : (er zijn ook andere data, zoals DATUM UITGEBRACHT Verenigd Koninkrijk : 17 april 1964 16, 17 of 18 januari genoemd Verenigd Koninkrijk : Down Home Girl I Can’t Be Satisfi ed 15 januari 1965 Label Decca als datum van uitbrengen) 14 augustus 1964 You Can’t Catch Me Pain In My Heart Label Decca REF : LK 4605 Label Decca Label Decca Time Is On My Side Off The Hook REF : LK 4661 12 weken op nummer 1 REF : DFE 8560 REF : DFE 8590 10 weken op nummer 1 What A Shame Susie Q Grown Up Wrong TH TH TH ROING (Get Your Kicks On) Route 66 FIVE I Just Want To Make Love To You Honest I Do ROING ROING I Need You Baby (Mona) Now I’ve Got A Witness (Like Uncle Phil And Uncle Gene) Little By Little H ROLLIN TONS NOW VRNIGD TATEN EBRUARI 965) I’m A King Bee Everybody Needs Somebody To Love / Down Home Girl / You Can’t Catch Me / Heart Of Stone / What A Shame / I Need You Baby (Mona) / Down The Road Carol Apiece / Off The Hook / Pain In My Heart / Oh Baby (We Got A Good Thing SONS Tell Me (You’re Coming Back) If You Need Me Goin’) / Little Red Rooster / Surprise, Surprise. -

Linn Lounge Presents... the Rolling Stones

Linn Lounge Presents... The Rolling Stones Welcome to Linn Lounge presents… ‘The Rolling Stones’ Tonight’s album, ‘Grr’ tells the fascinating ongoing story of the Greatest Rock'n'Roll Band In The World. It features re-masters of some of the ‘Stones’ iconic recordings. It also contains 2 brand new tracks which constitute the first time Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Charlie Watts and Ronnie Wood have all been together in the recording studio since 2005. This album will be played in Studio Master - the highest quality download available anywhere, letting you hear the recording exactly as it left the studio. So sit back, relax and enjoy as you embark on a voyage through tonight’s musical journey. MUSIC – Muddy Waters, Rollin’ Stone via Spotify (Play 30secs then turn down) It all started with Muddy Waters. A chance meeting between 2 old friends at Dartford railway station marked the beginning of 50 years of rock and roll. In the early 1950s, Keith Richards and Mick Jagger were childhood friends and classmates at Wentworth Primary School in Kent until their families moved apart.[8] In 1960, the pair met again on their way to college at Dartford railway station. The Chuck Berry and Muddy Waters records that Jagger carried revealed a mutual interest. They began forming a band with Dick Taylor and Brian Jones from Blues Incorporated. This band also contained two other future members of the Rolling Stones: Ian Stewart and Charlie Watts.[11] So how did the name come about? Well according to Richards, Jones christened the band during a phone call to Jazz News. -

Van Gogh Museum Journal 2002

Van Gogh Museum Journal 2002 bron Van Gogh Museum Journal 2002. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam 2002 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_van012200201_01/colofon.php © 2012 dbnl / Rijksmuseum Vincent Van Gogh 7 Director's foreword In 2003 the Van Gogh Museum will have been in existence for 30 years. Our museum is thus still a relative newcomer on the international scene. Nonetheless, in this fairly short period, the Van Gogh Museum has established itself as one of the liveliest institutions of its kind, with a growing reputation for its collections, exhibitions and research programmes. The past year has been marked by particular success: the Van Gogh and Gauguin exhibition attracted record numbers of visitors to its Amsterdam venue. And in this Journal we publish our latest acquisitions, including Manet's The jetty at Boulogne-sur-mer, the first important work by this artist to enter any Dutch public collection. By a happy coincidence, our 30th anniversary coincides with the 150th of the birth of Vincent van Gogh. As we approach this milestone it seemed to us a good moment to reflect on the current state of Van Gogh studies. For this issue of the Journal we asked a number of experts to look back on the most significant developments in Van Gogh research since the last major anniversary in 1990, the centenary of the artist's death. Our authors were asked to filter a mass of published material in differing areas, from exhibition publications to writings about fakes and forgeries. To complement this, we also invited a number of specialists to write a short piece on one picture from our collection, an exercise that is intended to evoke the variety and resourcefulness of current writing on Van Gogh. -

Pepe Aguilar Recibirá Premio Billboard EL UNIVERSAL México, DF

11/10/2012 22:43 Cuerpo E Pagina 3 Cyan Magenta Amarillo Negro KIOSKO | VIERNES 12 DE OCTUBRE DE 2012 | EL SIGLO DE DURANGO 3 EN PANTALLA Estrenos Frankenweenie.- Tras las El código del miedo.- Atrocious.- El4de inesperada muerte de su Una muchacha jóven abril de 2010 una parte querido perro Sparky, el china tiene secretos de de la familia joven Victor aprovecha el armas de destrucción Quintanilla Atauri fue poder de la ciencia para masiva, las cuales encontrada muerta en devolver a su mejor amigo a quieren conseguir tanto su casa de campo. La la vida - con algunos ajustes la Mafia china como la policía descubrió la menores. Intenta esconder mafia rusa. La muchacha existencia de cintas de las costuras caseras de su se reúne con un Soldado vídeo con 37 horas de creación pero cuando Sparky de Fortuna y él la grabación. Aquel salga, los compañeros de protege del rapto y el mismo mes de abril, Victor, sus profesores y la asesinato por los agentes dos productores vieron ciudad entera aprenderán de la Mafia rusa y china la oportunidad de que conseguir una nueva en los EU, ambos de los crear una película a correa que lo agarre a la vida cuales compiten para partir del material PUNTUACIÓN PUNTUACIÓN PUNTUACIÓN puede ser monstruoso. encontrar a la muchacha. encontrado. Nuevo material. La agrupación presentó “Doom And Gloom”, una canción inédita de ritmos pegadizos, bien acogida por la crítica, que sirve de adelanto de su álbum recopilatorio “GRRR!”. AGENCIAS Premio Legado Musical. El cantante será reconoci- do el próximo 18 de octubre. -

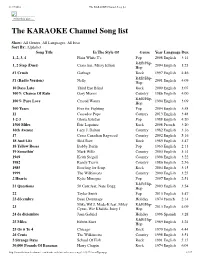

The KARAOKE Channel Song List

11/17/2016 The KARAOKE Channel Song list Print this List ... The KARAOKE Channel Song list Show: All Genres, All Languages, All Eras Sort By: Alphabet Song Title In The Style Of Genre Year Language Dur. 1, 2, 3, 4 Plain White T's Pop 2008 English 3:14 R&B/Hip- 1, 2 Step (Duet) Ciara feat. Missy Elliott 2004 English 3:23 Hop #1 Crush Garbage Rock 1997 English 4:46 R&B/Hip- #1 (Radio Version) Nelly 2001 English 4:09 Hop 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind Rock 2000 English 3:07 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris Country 1986 English 4:00 R&B/Hip- 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 1994 English 3:09 Hop 100 Years Five for Fighting Pop 2004 English 3:58 11 Cassadee Pope Country 2013 English 3:48 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan Pop 1988 English 4:20 1500 Miles Éric Lapointe Rock 2008 French 3:20 16th Avenue Lacy J. Dalton Country 1982 English 3:16 17 Cross Canadian Ragweed Country 2002 English 5:16 18 And Life Skid Row Rock 1989 English 3:47 18 Yellow Roses Bobby Darin Pop 1963 English 2:13 19 Somethin' Mark Wills Country 2003 English 3:14 1969 Keith Stegall Country 1996 English 3:22 1982 Randy Travis Country 1986 English 2:56 1985 Bowling for Soup Rock 2004 English 3:15 1999 The Wilkinsons Country 2000 English 3:25 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue Pop 2007 English 2:51 R&B/Hip- 21 Questions 50 Cent feat. Nate Dogg 2003 English 3:54 Hop 22 Taylor Swift Pop 2013 English 3:47 23 décembre Beau Dommage Holiday 1974 French 2:14 Mike WiLL Made-It feat. -

PP2 SHOOTING DRAFT.Fdx

"PITCH PERFECT 2" Written by Kay Cannon Based on the book by Mickey Rapkin This material is the property of UNIVERSAL PICTURES and is intended for us only by authorized personnel. Distribution of disclosure of this material to unauthorized persons is prohibited. The sale, copying, or reproduction of this material in any form or medium, in whole or in part, is strictly prohibited. As the Universal logo appears on screen, we hear Universal’s theme song being sung a cappella by... 1 INT. KENNEDY CENTER - PRESS BOX 1 Our a cappella commentators, JOHN and GAIL. JOHN Excited, Gail? GAIL If I weren’t, would I be wearing a diaper under this dress? As John speaks, we HEAR a marching band play. JOHN (V.O.) Welcome back, a cappella enthusiasts! 2 INT. KENNEDY CENTER - STAGE - AUGUST 2014 - NIGHT 2 A MILITARY BAND heads off stage as THE BARDEN BELLAS get set. JOHN I’m John Smith and sitting to my right is Gail Abernathy-McCadden- Feinberger. GAIL (pointing to wedding ring) This one’s gonna stick, John. JOHN Well you saved the Jew for last. GAIL (gleefully nodding) I did, I did. JOHN You’re listening to Let’s Talk- appella, the world’s premiere downloadable a cappella podcast. GAIL We are coming to you live from our nation’s capitol where the Barden University Bellas are about to rock the historic Kennedy Center. (CONTINUED) "Pitch Perfect 2" SHOOTING DRAFTS 5-11-14 2. 2 CONTINUED: 2 The BELLAS: BECA, CHLOE, Lilly, STACIE, CYNTHIA ROSE, JESSICA, ASHLEY and a small Latina girl, FLORENCIA FUENTES (FLO). -

H E a B E R Subscription $9 Published Weeky USPS125-420 of LYNDHURST THURSDAY, OCTOBER 9, 1997 Third Ave

Bo o at the zoo The heat is on Bronx Zoo Halloween treat And with just the touch of a button S'- e 4 See page 8 m t ' ' THE COMMERCIAL Published at 251 Ridge Road, Lyndhurst 2 5 4 Second Class Postage Paid At Rutherford, NJ 07070 H e a b e r Subscription $9 Published Weeky USPS125-420 OF LYNDHURST THURSDAY, OCTOBER 9, 1997 Third Ave. thief still at large; may have apartment keys By J o i.yn G arner Thc September 26 burglary of a Lyndhurst apartment building re Kelly and DiGaetano mains unsolved and the suspect or suspects are still at large announce tax relief According to police, thc superin tendent of a building located at 551 Assemblyman John V. Kelly and Third Avenue, just off Ridge Road Assembly M ajority Leader Paul called authorities at about 3 PM DiGaetano (both R-36) announced reporting that their apartment was yesterday that the township of burglarized. Lyndhurst will receive taxpayer re Complicating matters, policc dis lief in the amount of $700,000. Tim e to shut dow n- On Thursday, October 1, Mayor James Guida with the cooperation of the Building I covered that thc thief also stole thc The funds, which are in the form Department and the Fire Official & Fire Department ordered the building being used by Bellavia Buick on keys to thc other apartments in thc of discretionary aid, will be dispersed Riverside Ave to be closed down On Wednesday, Sept. 30, the Mayor and Commissioner Peter Russo b u ild in g by the Department of Community inspected the site and found it to be not only a fire hazard but completely unsafe with many m ajor violations Policc then waited for thc resi Affairs.