America's Last Primitive Area Is It Time for Wilderness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Summer Vacation in Arizona

JUNE 1959 FORTY CENTS IN THIS ISSUE: ASummer Vacation In Arizona VOL. XXXV NO. 6 JUNE 1959 You can't always tell by the cool calculations of the RAYMOND CARLSON, Editor calendar or the bobbing babble of the thermometer. The GEORGE M. A VEY, Art Editor testimony of the wayward sun is not always reliable. You JAMES E . STEVENS, Business Manager awaken one fine morning and for some indefinable reason LEGEND you know summer is just around the corner. There is a languor in the shadows and a soft sleepiness in the air that ARIZONA'S TIM BERED TREASURE 2 FORESTS OF STATE PRODUCE RICHES bespeak summer's approach. There is a drowsiness in the IN I.UMB E, R, Rf:C REATJO NAL ACTIVITIES. gossip of the green, green leaves caressed by the soft, THE PARADOX OF A LA\'A FLOW 8 warm breeze. You know that spring has had her Ring VOLCANIC ERUPTIONS IN NORTHERN ARIZONA CHANGED ENRICHED LAND. and another season is getting ready to cavort over the AN ARIZONA S ui\ Ii\TER VACATION landscape. //~-- ~.-.....,, ~ - JF YOU PL AN YO UR VACATION W"ELL, YOU'LL HAVE ONE COOL AND CAREFREE. we afe -n'i uch conce'_r.n'ea with summer this issue and SNOW IN JuLY 28 our p/ ges are an invitatiot~ ''.1} y ou to plan a cool and WHCN YOU CLIMB SA N FRANCISCO PEAKS careffee vacation in, our state.·, AiJ 'Of Northern Arizona ' , ,_ •. • IN J ULY YOU RUN INTO SURPRISES. is a huge sm:nmer v,ac~ti911 playgrouh~, where the scenery LONG MEADOW RANCH 34 is superb aricF1th.~' )-v:i::i:ther admirable -' for those who like Tms RANCH IN YAVAPAI COUNTY IS ONE //;') \ . -

Land Areas of the National Forest System

United States Department of Agriculture Land Areas of the National Forest System As of September 30, 2018 Forest Service WO Lands FS-383 November 2018 United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Land Areas of the WO, Lands National Forest FS-383 System November 2018 As of September 30, 2018 Published by: USDA Forest Service 1400 Independence Ave., SW Washington, D.C. 20250-0003 Web site: https://www.fs.fed.us/land/staff/lar-index.shtml Cover photo courtesy of: Chris Chavez Statistics are current as of: 10/15/2018 The National Forest System (NFS) is comprised of: 154 National Forests 58 Purchase Units 20 National Grasslands 7 Land Utilization Projects 17 Research and Experimental Areas 28 Other Areas NFS lands are found in 43 States as well as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. TOTAL NFS ACRES = 192,948,059 NFS lands are organized into: 9 Forest Service Regions 112 Administrative Forest or Forest-level units 506 Ranger District or District-level units The Forest Service administers 128 Wild and Scenic Rivers in 23 States and 446 National Wilderness Areas in 39 States. The FS also administers several other types of nationally-designated areas: 1 National Historic Area in 1 State 1 National Scenic Research Area in 1 State 1 Scenic Recreation Area in 1 State 1 Scenic Wildlife Area in 1 State 2 National Botanical Areas in 1 State 2 National Volcanic Monument Areas in 2 States 2 Recreation Management Areas in 2 States 6 National Protection Areas in 3 States 8 National Scenic Areas in 6 States 12 National Monument Areas in 6 States 12 Special Management Areas in 5 States 21 National Game Refuge or Wildlife Preserves in 12 States 22 National Recreation Areas in 20 States Table of Contents Acreage Calculation ........................................................................................................... -

Water, Summer 2008

Restoring Connections Vol. 11 Issue 2 Summer 2008 Newsletter of the Sky Island Alliance In this issue: A River Runs Beneath It by Randy Serraglio 4 Time and the Aquifer: Models and Long-term Thinking Water… by Julia Fonseca 5 Street and Public Rights-of-Way: Community Corridors of Heat & Dehydration OR Green Belts of Coolness & Rehydration by Brad Lancaster 6 A New Path for Water Use by Melissa Lamberton 7 The Power of Water by Janice Przybyl 8 Our special pull-out section on Ciénegas Monitoring Water with Remote Cameras by Sergio Avila 9 Waste Water / Holy Water by Ken Lamberton 10 Coyote Wells by Julia Fonseca 12 Finding Water in the Desert by Gary Williams 12 H2Oly Stories by Doug Bland 13 Restaurant Review: The Adobe Café & Bakery by Mary Rakestraw 14 Volunteers Make It Happen Rio Saracachi at Rancho Agua Fria in Sonora. by Sarah Williams 16 From the Director’s Desk: Swimming Holes and Groundwater by Matt Skroch, Executive Director Rivers and springs have been used to our several decades, or centuries, the water table will agricultural advantage for 12,000 years here, once again seep upwards to ground level, and though unsustainable groundwater mining is a those low points on the landscape we call rivers relatively new phenomena. We’ve discovered will flow once again. other temporary ways around the problem of increasing water scarcity — billions of dollars Either choice will eventually lead nature back to spent to pump water uphill for 330 miles being better days. The difference being that one choice Few experiences compare to the exhilaration of one spectacular example. -

Appendix L - List of Tier 3, Tier 2, and Tier 2.5 Waters

Multi-Sector General Permit (MSGP) L-1 Appendix L - List of Tier 3, Tier 2, and Tier 2.5 Waters EPA’s MSGP has special requirements for discharges to waters designated by a state or tribe as Tier 2/2.5 or Tier 3 for antidegradation purposes under 40 CFR 131.12(a). See Parts 1.1.4.8 and 1.1.4.10 The list below is provided as a resource for operators who must determine whether they discharge to a Tier 2/2.5 or Tier 3 water. Only Tier 2/2.5 or Tier 3 waters specifically identified by a water quality standard authority (e.g., a state, territory, or tribe) are identified in the table below. Many authorities evaluate the existing and protected quality of the receiving water on a pollutant-by-pollutant basis and determine whether water quality is better than the applicable criteria that would be affected by a new discharger or a new source or an increase in an existing discharge of the pollutant. In instances where water quality is better, the authority may choose to allow lower water quality, where lower water quality is determined to be necessary to support important social and economic development. Permittees are not required to identify those waters which are evaluated on an individual basis. Permit Areas of Coverage/Where EPA Is Permitting Authority Number MAR050000 Commonwealth of Massachusetts, except Indian Country lands Tier 2, Tier 2.5, and 3 waters are identified and listed in the Massachusetts Water Quality Standards 314 CMR 4.00. Surface water qualifiers that correspond with Tier classifications are defined at 314 CMR 4.06(1)(d)m and listed in tables and figures at the end of 314 CMR 4.06. -

Table 7 - National Wilderness Areas by State

Table 7 - National Wilderness Areas by State * Unit is in two or more States ** Acres estimated pending final boundary determination + Special Area that is part of a proclaimed National Forest State National Wilderness Area NFS Other Total Unit Name Acreage Acreage Acreage Alabama Cheaha Wilderness Talladega National Forest 7,400 0 7,400 Dugger Mountain Wilderness** Talladega National Forest 9,048 0 9,048 Sipsey Wilderness William B. Bankhead National Forest 25,770 83 25,853 Alabama Totals 42,218 83 42,301 Alaska Chuck River Wilderness 74,876 520 75,396 Coronation Island Wilderness Tongass National Forest 19,118 0 19,118 Endicott River Wilderness Tongass National Forest 98,396 0 98,396 Karta River Wilderness Tongass National Forest 39,917 7 39,924 Kootznoowoo Wilderness Tongass National Forest 979,079 21,741 1,000,820 FS-administered, outside NFS bdy 0 654 654 Kuiu Wilderness Tongass National Forest 60,183 15 60,198 Maurille Islands Wilderness Tongass National Forest 4,814 0 4,814 Misty Fiords National Monument Wilderness Tongass National Forest 2,144,010 235 2,144,245 FS-administered, outside NFS bdy 0 15 15 Petersburg Creek-Duncan Salt Chuck Wilderness Tongass National Forest 46,758 0 46,758 Pleasant/Lemusurier/Inian Islands Wilderness Tongass National Forest 23,083 41 23,124 FS-administered, outside NFS bdy 0 15 15 Russell Fjord Wilderness Tongass National Forest 348,626 63 348,689 South Baranof Wilderness Tongass National Forest 315,833 0 315,833 South Etolin Wilderness Tongass National Forest 82,593 834 83,427 Refresh Date: 10/14/2017 -

Case 4:21-Cv-00020-SHR Document 1 Filed 01/14/21 Page 1 of 29

Case 4:21-cv-00020-SHR Document 1 Filed 01/14/21 Page 1 of 29 Kelly E. Nokes, applicant for pro hac vice Colorado Bar No. 51877 Western Environmental Law Center P.O. Box 218 Buena Vista, Colorado 81211 Tel: 575-613-8051 [email protected] Matthew K. Bishop, applicant for pro hac vice Montana Bar No. 9968 Western Environmental Law Center 103 Reeder’s Alley Helena, Montana 59603 Tel: 406-324-8011 [email protected] Attorneys for Plaintiffs IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF ARIZONA Western Watersheds Project, a non-profit No. organization; and Wilderness Watch, a non- profit organization, COMPLAINT Plaintiffs, vs. Sonny Perdue, as Secretary of the United States Department of Agriculture; the United States Department of Agriculture, a federal department; the United States Forest Service, a federal agency; Erick Stemmerman, as District Ranger for the Glenwood Ranger District on the Gila National Forest; and Ed Holloway Jr., as District Ranger for the Clifton Ranger District on the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest, Federal Defendants. Case 4:21-cv-00020-SHR Document 1 Filed 01/14/21 Page 2 of 29 1 INTRODUCTION 2 1. Western Watersheds Project and Wilderness Watch (collectively, “Plaintiffs”), 3 bring this civil action for declaratory relief against the above-named Federal Defendants 4 (collectively, the “Forest Service”) under the Administrative Procedure Act (“APA”), 5 5 U.S.C. § 701 et seq., for violations of the National Environmental Policy Act (“NEPA”), 6 42 U.S.C. § 4321 et seq. 7 2. This case challenges the Forest Service’s Stateline Range Environmental 8 Assessment and three associated Decision Notices and Findings of No Significant 9 Impacts authorizing livestock grazing on fourteen allotments expanding over 270,000 10 acres in the Apache-Sitgreaves and Gila National Forests in Arizona and New Mexico 11 (collectively, the “Stateline project”). -

Bluethe Blue Range Primitive Area Is the Last Primitive Area in America. All the Rest Were Given Wilderness Protection Years A

THE BLUE RANGE PRIMITIVE AREA IS THE LAST PRIMITIVE AREA IN AMERICA. ALL THE REST WERE GIVEN WILDERNESS PROTECTION YEARS AGO. IS IT TIME TO DO THE SAME FOR THE BLUE? BY KELLY VAUGHN The evergreens of Eastern Arizona’s Blue Range Primitive Area frame a view of New Mexico’s Blue Range Wilderness to the east. While New Mexico’s portion of the Blue Range has received wilderness protection, Arizona’s remains a primitive area — the last such area in the U.S. | JACK DYKINGA BLUE16 JULY 2015 www.arizonahighways.com 17 LONG AGO AND OFTEN I DREAMED THE BLUE. Before I walked into and through parts of it, I awoke from ronmentalism and policy, of the slow evolution of a land that it — sleep-drunk on the memory of being lost and found in became lost without political advocates. woods thick and wild. In 1929, on the heels of Leopold’s charge to designate the nearby Then, one October morning, I set into the Blue Range Primi- Gila Wilderness, the U.S. Forest Service published its “L-20” regu- tive Area and trespassed back into the dream. lation to designate primitive areas within national forests. The last of the federally designated primitive areas in the The document applauded the concept of wilderness but national-forest system, the Blue spans 199,505 acres along the didn’t do much to permanently protect wild lands. In fact, it state’s far-eastern edge, cutting a rough spine between Arizona kept intact existing Forest Service capability to change boundar- and the Blue Range Wilderness of New Mexico. -

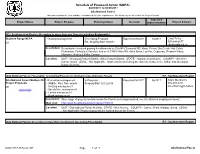

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 04/01/2017 to 06/30/2017 Gila National Forest This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 04/01/2017 to 06/30/2017 Gila National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact R3 - Southwestern Region, Occurring in more than one Forest (excluding Regionwide) Stateline Range NEPA - Grazing management Developing Proposal Expected:09/2018 10/2018 Carol Telles EA Est. Scoping Start 10/2017 505-894-6677 [email protected] Description: Re-authorize livestock grazing for allotments on Gila NF-Glenwood RD: Alma, Citizen, Dry Creek, Holt Gulch, Pleasanton, Potholes & Sacaton; and on A-S NF-Clifton RD: Alma Mesa, Lop Ear, Copperas, Pleasant Valley, Blackjack, Hickey & Keller Canyon Location: UNIT - Glenwood Ranger District, Clifton Ranger District. STATE - Arizona, New Mexico. COUNTY - Greenlee, Catron, Grant. LEGAL - Not Applicable. Allotments located along the stateline between the Clifton and Glenwood Ranger Districts. Gila National Forest, Forestwide (excluding Projects occurring in more than one Forest) R3 - Southwestern Region Gila National Forest Multiple CE - Recreation management In Progress: Expected:06/2017 06/2017 Adam Mendonca Project Proposals - Wildlife, Fish, Rare plants Scoping Start 12/12/2016 575-388-8201 CE - Grazing management [email protected] *UPDATED* - Special use management - Facility management - Road management Description: Wide range of projects located across the Forest are being proposed, see the attached scoping document. Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=50733 Location: UNIT - Gila National Forest All Units. STATE - New Mexico. COUNTY - Catron, Grant, Hidalgo, Sierra. LEGAL - Not Applicable. Proposed projects are located across the Forest. -

Gila National Forest This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 01/01/2007 to 03/31/2007 Gila National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring Nationwide Aerial Application of Fire - Fuels management In Progress: Expected:07/2007 08/2007 Christopher Wehrli Retardant 215 Comment period legal 202-205-1332 EA notice 07/28/2006 fire [email protected] *NEW LISTING* Description: The Forest Service proposes to continue the aerial application of fire retardant to fight fires on National Forest System lands. An environmental analysis will be conducted to prepare an Environmental Assessment on the proposed action. Web Link: http://www.fs.fed.us/fire/retardant/index.html. Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. Nation Wide. Gila National Forest, Forestwide (excluding Projects occurring in more than one Forest) R3 - Southwestern Region Management Indicator Species - Land management planning Completed Actual: 09/29/2006 01/2007 Debby Hyde-Sato EA 505-388-8483 [email protected] Description: Revise Forest Plan Management Indicator Species list Location: UNIT - Gila National Forest Units. STATE - New Mexico. COUNTY - Catron, Grant, Hidalgo, Sierra. LEGAL - T1S-T10N, T6S-18S, R1-13W, R30E-32E. Forest-wide. University of Arizona Shrew - Special use management On Hold N/A N/A John Baumberger Research 505-388-8238 DM [email protected] Description: Research on shrews Location: UNIT - Gila National Forest All Units. STATE - New Mexico. COUNTY - Catron, Grant, Sierra. LEGAL - Forest-wide. -

“Thinking Like a Mountain”

“Thinking Like a Mountain” Escudilla Wilderness Additions Wilderness Study Area Proposal Apache-Sitgreaves National Forests Prepared by: The White Mountain Conservation League http://azwmcl.org 2009 “Each hollow seemed its own small world, soaked in sun, fragrant with juniper, and cozy with the chatter of pinon jays. But top out on a ridge and you at once became a speck into an immensity. On its edge hung Escudilla.” Aldo Leopold “Escudilla” A Sand County Almanac. Escudilla Wilderness Additions WSA Updated 4-2-2009 page 1 White Mountain Conservation League Mission The White Mountain Conservation League (WMCL), a 503c organization, is a local action group dedicated to sustaining and enhancing the White Mountain ecosystems and communities. The spectacular White Mountain region provides habitat for hundreds of plant and animal species. The WMCL embraces and encourages stewardship of all components of the region’s diverse ecosystems and recognizes their value to our regional economic vitality and quality of life. The WMCL objectives of promoting natural resources stewardship and sustainability are achieved by active participation at all levels of land and wildlife management decision making to address environmental issues important to our membership and community. page 2 Updated 4-2-2009 Escudilla Wilderness Additions WSA Acknowledgments The White Mountain Conservation League (WMCL) would like to thank all of the members who spent so many hours and days in the fi eld inventorying the potential wilderness quality of lands on Escudilla Mountain. Those members include Dave Denali, Jonathon Frenzen, Tom Hollender, Don Hoffman, Dave and Kim Holaway, Cathy and Mike Pensinger, Ann and Steve McQueen, Candy Cook, Cliff Livingston and his son. -

Of Doña Ana County

www.nmwild.org DoñaAna by Stephen Capra When working to protect wild places in New Mexico, one need only look south to see large tracts of wild public lands that have the potential of being put into the National Wilderness Preservation a look at the wildlands of Doña Ana County System. From the Boot Heel to Otero Mesa and north to the Apache Kid and Quebradas, southern New Mexico is, in many ways, some of the wildest coun- try left in the Rocky Mountain West. But like so many other places here, it faces a myriad of threats. From oil and gas drill- ing, to off-road vehicles to urban sprawl, the threats are real. These threats make Wilderness designation essential to the long-term protection of these wild places. Despite the tough political cli- mate related to wilderness, there are indications of a bi-partisan willingness to work together to protect some key areas in Doña Ana County. Wilderness remains one of the best ideas we Americans have ever had. With the passage of the Wilderness Act in 1964, public lands were, for the first time, set aside for their scenic, biologi- cal and recreational value. Protecting OJITO: an area as wilderness prevents oil and NOW IT’S FOREVER gas development, mining, logging and off-road vehicle use, but still allows for cattle grazing and horseback riding and WILD! packing. See Page 3 see Doña Ana, pg. 12 ©2005 Ken Stinnett s t e p h e n c a p r a • e x e c u t i v e d i r e c t o r Notes from the Executive Director As we come to the close of 2005, we can look back and see that it has been a very good year indeed for wilderness in New Mexico. -

94 Stat. 3228 Public Law 96-550—Dec

PUBLIC LAW 96-550—DEC. 19, 1980 94 STAT. 3221 Public Law 96-550 96th Congress An Act To designate certein National Forest System lands in the State of New Mexico for Dec. 19, 1980 inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System, and for other [H.R. 8298] purposes. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, National Forest System lands, N. Mex. TITLE I Designation. SEC. 101. The purposes of this Act are to— (1) designate certain National Forest System lands in New Mexico for inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System in order to promote, perpetuate, and preserve the wilder ness character of the land, to protect watersheds and wildlife habitat, preserve scenic and historic resources, and to promote scientific research, primitive recreation, solitude, physical and mental challenge, and inspiration for the benefit of all the American people; (2) insure that certain other National Forest System lands in New Mexico be promptly available for nonwilderness uses including, but not limited to, campground and other recreation site development, timber harvesting, intensive range manage ment, mineral development, and watershed and vegetation manipulation; and (3) designate certain other National Forest System land in New Mexico for further study in furtherance of the purposes of the Wilderness Act. 16 use 1131 SEC. 102. (a) In furtherance of the purposes of the Wilderness Act, note. the following National Forest System lands in the State of New Mexico are hereby designated as wilderness, and therefore, as compo nents of the National Wilderness Preservation System— (1) certain lands in the Gila National Forest, New Mexico, 16 use 1132 which comprise approximately two hundred and eleven thou note.