September-October 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

99 News Profile

OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION OF WOMEN PILOTS 3 3h e m s ~ < AUGUST / SEPTEMBER 1973 The wind donee did it ! ih e HO iw iu s AUGUST/SEPTEMBER 1973 VOLUME 15 NUMBER 7 THE NINETY-NINES, INC. The Will Rogers World Airport International Headquarters International President Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73159 Return Form 3579 to above address 2nd Class Postage pd. at North Little Rock. Ark. As I left Toronto last year my mind was filled with fresh Publisher Lee Keenihan memories of the Hyatt-Regency, Fox-Den Farms, Button- Managing Editor..........................Mardo Crane ville, Canadian customs and all the 99s who made the Assistant E d ito r............................. Betty Hicks convention a tremendous success. On the way home I Art Director Betty Hagerman realized what a great challenge there was in the year a- Production Manager Ron Oberlag head tor the 99s and for me as President. The exciting Circulation Manager Loretta Gragg goals proposed offered a new opportunity to widen hori zons and strengthen the impact of the organization on the Contributing Editors........................Mary Foley aviation community. Virginia Thompson In September, I attended the South Central Section Director of Advertising.............. Maggie Wirth meeting in Dallas as the first official function; this was followed by the North Central Section meeting in Illinois. Susie Sewell The Sacramento chapter members in California cele brated the 25th anniversary of the founding of their chap Contents ter on November 17th and it was a joy to share with them the review of their Powder Puff Derby — Highlights & Results 2-5 many accomplishments. -

USA Price List (.PDF File)

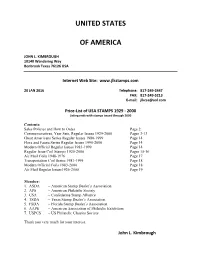

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA JOHN L. KIMBROUGH 10140 Wandering Way Benbrook Texas 76126 USA Internet Web Site: www.jlkstamps.com 20 JAN 2016 Telephone: 817-249-2447 FAX: 817-249-5213 E-mail: [email protected] Price-List of USA STAMPS 1929 - 2000 Listing ends with stamps issued through 2000 Contents: Sales Policies and How to Order Page 2 Commemoratives, Year Sets, Regular Issues 1929-2000 Pages 3-13 Great Americans Series Regular Issues 1980-1999 Page 14 Flora and Fauna Series Regular Issues 1990-2000 Page 14 Modern Official Regular Issues 1983-1999 Page 14 Regular Issue Coil Stamps 1920-2000 Pages 15-16 Air Mail Coils 1948-1976 Page 17 Transportation Coil Series 1981-1995 Page 18 Modern Official Coils 1983-2000 Page 18 Air Mail Regular Issues1926-2000 Page 19 Member: 1. ASDA -- American Stamp Dealer’s Association 2. APS -- American Philatelic Society 3. CSA -- Confederate Stamp Alliance 4. TSDA -- Texas Stamp Dealer’s Association 5. FSDA -- Florida Stamp Dealer’s Association 6. AAPE -- American Association of Philatelic Exhibitors 7. USPCS -- US Philatelic Classics Society Thank you very much for your interest. John L. Kimbrough Sales Policies and How to Order 1. Orders from this USA Listing may be made by mail, FAX, telephone, or E-mail ([email protected]). If you have Internet access, the easiest way to order is to visit my web site (http://www.jlkstamps.com) and use my secure Visa/Mastercard on-line credit card order form. 2. Please order using the Scott Numbers only (may also use a description of the stamp as well). -

United States Women in Aviation Through World War I

United States Women in Aviation through World War I Claudia M.Oakes •^ a. SMITHSONIAN STUDIES IN AIR AND SPACE • NUMBER 2 SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of "diffusing knowledge" was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the Institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This theme of basic research has been adhered to through the years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, commencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Astrophysics Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to the Marine Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology Smithsonian Studies in Air and Space Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that report the research and collections of its various museums and bureaux or of professional colleagues in the world of science and scholarship. The publications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institutions throughout the world. Papers or monographs submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Press, subject to its own review for format and style, only through departments of the various Smithsonian museums or bureaux, where the manuscripts are given sub stantive review. -

JANUARY 1980 Volume 10 Number 1

XIII OLYMPIC ()()("")\'\i'INTER 'O'.CY.GAMES LAKE PlACJD l980 .. NICI WORLD JANUARY 1980 Volume 10 Number 1 Secretary of Transportation Neil E. Goldschmidt Administrator. FAA Langhorne M. Bond Assistant Administrator-Public Affairs Jerome H. Doolittle Chief-Public & Employee Communications Div .. John G. Leyden Editor. Leonard Samuels Ari Director. Eleanor M. Maginnis FAA WORLD is published monthly for the em ployees of the Department of Trans portation/Federal Aviation Administration and is the official FAA employee publication. It is prepared by the Public & Employee Communications Division, Office of Public Af fairs. FAA, 800 Independence Ave. SW, Washington, D.C. 20591. Articles and photos for FAA World should be submitted directly to regional FAA public affairs officers: Mark Weaver-Aeronautical Center; Clifford Cernick-Alaskan Region; Joseph Frets Central Region; Robert Fulton-Eastern Re gion; Neal Callahan-Great Lakes Region; Michael Benson-NAFEC; Mike Ciccarelli New England Region; Ken Shake-North west Region; George Miyachi-Pacific-Asia Region; David Myers-Rocky Mountain Re gion; Jack Barker-Southern Region; K. K. Jones-Southwest Region; Alexander Garvis-Western Region. Opposite: Ruth Law taking off from Chicago's Grant Park on a flight that broke the U.S. non stop cross-country record and world record for women and the second-best world nonstop cross-country record. She ran out of fuel on Nov. 19. 1916, at Hornell, N. Y., and completed her flight to New York City the next day. Insets: Blanche Scott, the only woman taught to fly by Glenn Curtiss and possibly the first woman to solo on Sept. 2, 1910. Bessie Coleman, the first black woman to earn a pilot's license is shown with aircraft designer-builder Tony Fok ker in The Netherlands in the early 1920s. -

Women Airforce Service Pilots of World War II

From Barnstormers to Military Pilots: The Women Airforce Service Pilots of World War II Amber Dzelzkalns HISTORY 489 Capstone Advisor: Dr. Patricia Turner Cooperating Professor: Earl Shoemaker Copyright for this work is owned by the author. This digital version is published by McIntyre Library, University of Wisconsin Eau Claire with the consent of the author. Table of Contents I. Abstract……………………………………………………………….……………………….3 II. Historiography.………………………………………………….…………………….……….4 III. Women In Aviation from 1910-1939………..………………………………………….……10 IV. The Debate of the Use of Women Pilots (1939-1941): The Formation of the WASP, WAC and WAVE...….….……………….……………………………………….…………………16 V. 1942 and the Two Women‟s Auxiliaries….………..………………….……………….……19 VI. Adversity and the Push to be Militarized…………………………………………………….31 VII. After Deactivation……………..…………………………………….…………………….…38 VIII. Epilogue……………………………………………………………….……………….…….41 IX. Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………………42 X. Appendices …………………………………………………………….……………………45 2 I: Abstract Women have been flying since 1910, and since that time, they have faced discrimination.1 During World War II, women pilots were utilized for the first time by the government for the war effort. This paper will argue that early women “aviatrixes”, a female pilot/aviator, were able to set the stage for the Women Airforce Service Pilots of World War II. It also will argue that in order for women to become military pilots, they had to overcome adversity in many forms, including denial of light instruction, lack of access to jobs, low pay, onerous and often dangerous assignments. They had the misfortune of facing disparaging public opinion in mid-1944, which led to their military deactivation. Women aviators were able to overcome the gender stereotypes in early aviation, and because of their success, women were able to fly every type of plane the Army Air Force (AAF) had in their arsenal the second world war. -

05-23-1918 Katherine Stinson.Indd

This Day in History… May 23, 1918 First Commissioned Female Airmail Pilot On May 23, 1918, Katherine Stinson became the first woman hired by the post office to deliver airmail in the US. She had several other notable firsts and records in his short flying career. Born February 14, 1891, in Fort Payne, Alabama, Katherine’s family played an important role in early aviation. Her brother Eddie was an airplane manufacturer and her family ran a flight school. In 1912, at the age of 21, Stinson became just the fourth woman in the The airmail stamp in use country to earn her pilot’s license. The following year she became the first at the time of Katherine Stinson’s flight. woman to carry the US mail when she dropped mailbags over the Montana State Fair. Her sister Marjorie also flew an early experimental airmail route in Texas in 1915, for which she is sometimes considered the first female airmail pilot. Katherine Stinson became known as the “Flying Schoolgirl” and earned widespread attention for her daring aviation feats, earning up to $500 per appearance. In 1915, she became the first woman to perform a loop and created the “Dippy Twist Loop,” a loop with a snap roll at the top. Stinson also performed tricks at night, using flares attached to her plane’s wingtips. She was the first person, man or woman, to fly at night and the first to perform night skywriting. Stinson tried to serve as a combat pilot during World War I, but was denied. Instead, she helped train pilots at her family’s school and flew fundraising tours for the American Red 2017 Airplane Skywriting Cross. -

September 15, 1950 NINETY-NINES, Let Us SLANT Our Efforts This Year Toward a Common Goal and Make Our Influence Really Felt

PRESIDENT'S COLUMN Dear Members i Greetings to all members of The NINETY-NINES, Inc. Yes, we were incorporated in time for the Derby, thanks to the THE efforts of Chairman Augusta Roberts who will serve as our NINETY-NINES, Inc. "Resident Agent" in Delaware. INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION OF WOMEN PILOTS May I herein express my sincere appreciation to all who Affiliated with the National Aeronautic Association congratulated me by word, letter and telegram. And altho 1025 C o n n e c t ic u t A v e n u e W a s h in g t o n 6, D. C. it is my turn to push the throttle and help navigate this wonderful organization for the coming year, I know that each of you will share the responsibility ahead in order that we may MAKE THE FUTURE SPEAK FOR ITSELF. While your officers are working to create a fitting ser vice for the Ninety-Nines as a group in the event of con i v ' tinued war, we must carry on. I like to think that we are SERIOUS in SERVICE and SOCIAL in SPIRIT, and on that is based the following programs AIR AGE EDUCATION — FCR TEACHERS and INCREASED FLIGHT ACTIVITY PROGRAMS for MEM BERS. Not every community has CAP, Wing Scouting or an Air Marking program, but common to every 99 Chapter the world NEWS | over are TEACHERS. Let me quote from a Navy publication ! entitled, "Why we are interested in Air Age Educators" — LETTER "We are what you make us. Your students become our offi ♦ cers and men. -

F::R JULY -AUGUST 1959

f::r BALLOT FOR BOARD OF GOVERNORS IN THIS ISSUE * BNAT~ JULY -AUGUST 1959 VOLUME 16 NUMBER 7 Whole Number 170 A Officia l Journal of ±he Briiish Nor±h America Philatelic Society HAVE A SAFE . A ND HA PPY HOllOA Y! New Books FROM 50 PALL MALL, LONDON, S.W.l Pakistan: Overprints on Indian Stamps, 1948-49 By Col. D. R. Martin. A limited edition of a wonderfully comprehensive work. $4.40 including postage • Numeral Cancellations of the British Empire Compiled by Rev. H. H. Heins. Combined Alphabetical Listing: Cancellations which begin with, or con sist of, a letter or letters of the alphabet. Combined Numerical Listing: Cancellations which begin with a numeral. Over 5000 references. $3.00 including postage. • A Glossary of Abbreviations Found on Handstruck Stamps Compiled by Leslie Ray. A valuable work of reference for the Postal History student and those who collect covers. Nearly 500 references. A copy of the second edition will be sent post free t9 those who solve the queries. $ 1.00 including postage. • The above books may be ordered from our Agent in North America: R. W. Lyman, 31 Trout Street, Marblehead, Mass., U.S.A. Our full. literature list will be sent free on request . • ROBSON LOWE ,LTD ., PHILATELIC PUBLISHERS When replying to this adve1·tisement please mention that you saw it in "B.N.A. Topics" From Our PRIVATE TREATY Department CANADA PLATE BLOCKS ("Foursquares") A very complete collection contained in IS special Blleski a lbums und two other spring back binders. The collection commences with the 1937 Ic (Scou 231) and includes Air Post, Officials, Special Delivery, elc. -

Caltapex 2018

CALTAPEX 2018 October 13 and 14 Kerby Centre, 1133 - 7 Avenue SW Calgary, Alberta SHOW COMMITTEE Chairman Walter Herdzik Dealer liaison Ray Villeneuve Auction Jim Senecal and Doug Kollar Show catalogue Dale Speirs Posters Peter Fleck Show covers Dave Bartlet Exhibits Dave Russum Frames Walter Herdzik Awards and Palmares Donna Trathen Facilities and publicity Erika Peter Judges and Awards Banquet Janice Brookes PHILATELIC SOUVENIR OF CALTAPEX The theme of this year’s show is the centennial of the first airmail in Alberta, flown by Katherine Stinson on July 9, 1918, from Calgary to Edmonton. The cover was designed by Dave Bartlet. They are franked with a Picture Postage design showing Stinson, the design of which was not available at the time this catalogue went to press. 2 SCHEDULE OF EVENTS Events are in the Kerby Centre, except the Awards Banquet, which will be held at the Danish- Canadian Club, 727 - 11 Avenue SW. Tickets are required for the Banquet; all else is free. Saturday, October 13 Show opens 10h00 Canteen opens 11h00 Canteen closes 14h30 Show closes 17h00 Awards Banquet 18h00 to 22h00 Sunday, October 14 Show opens 10h00 Judge’s Critique 10h00 Canteen opens 11h00 Auction lots accepted 13h30 Canteen closes 14h30 Show closes 16h00 Auction begins 16h00 3 MESSAGE FROM THE SHOW CHAIRMAN by Walter Herdzik Welcome to CALTAPEX 2018. A little over a year has passed since the Calgary Philatelic Society and the local BNAPS Regional Group hosted the BNAPS 2017 show in Calgary. It is nice to get back to our usual facility for our annual show. -

Brookman Bargain Bonanza FALL 2011 EDITION PRICE $2.00 VOLUME 18, NO.4

Brookman Bargain Bonanza FALL 2011 EDITION PRICE $2.00 VOLUME 18, NO.4 ZEPP SET C13-15 VF IT’S TIME TO ORDER THE BRAND NEW C13 & C15 VLH FULL-COLOR C14 NH SUPER PRICE $1350.00 More Zepps 2012 BROOKMAN On page 35 PRICE GUIDE RY5 Firearms Transfer Tax Stamps F-VF NH. $35.00 each SAVE $5.00 2012 SPIRAL BOUND 1908 #12/14 Tagging Variety. Under PRICE GUIDE UV light, you can see precancel bars Retail $35.95 - Very scarce oddity. We only have a few. Your Price $49.95 per strip. Sale Price only $30.95 #630 WHITE PLAINS 2012 PERFECT BOUND F-VF LH SPECIAL PRICE GUIDE GROUP $249!! F-VF NH $450 Retail $31.95 - Sale Price only $26.95 Many different grades in stock including dot More information on Page 63 over S FALL 2011 INDEX FEATURING BROOKMAN’S FALL NET PRICE SALE - SAVE UP TO 70% - PAGES 25-40 PAGE 46-47 U.S. MINT SOUVENIR SHEETS SALE 2 U.S. MINT PLATE BLOCK SETS SALE 47 U.S. MINT UNCUT PRESS SHEETS SALE 3 U.S., U.N. & CANADA 1990-2010 SUPER SETS 48-49 U.S. MINT COIL PLATE NUMBER STRIPS SALE 4-5 U.S. UNUSED 1893-1935 COMMEMORATIVE SETS AND SINGLES SALE 50-51 U.S. MINT BOOKLET PANES SALE INCLUDING UNFOLDED PANES 5 U.S. FARLEY POSITION BLOCKS & PAIRS SALE 52-53 U.S. MINT COMPLETE BOOKLETS SALE 6-7 U.S. UNUSED 1894-1932 REGULAR ISSUE SETS AND SINGLES SALE 53 U.S. UNUSED COIL LINE PAIRS SALE 8-9 U.S. -

Women in the Aviation Industry

Running head: WOMEN IN AVIATION 1 Women in the Aviation Industry MAUREEN MUTISYA A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2010 WOMEN IN AVIATION 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ David L. Young, Brigadier General, USAF (Ret). Thesis Chair ______________________________ Samuel Smith, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Kurt Reesman, M.A.S. Committee Member ______________________________ Marilyn Gadomski, Ph.D. Assistant Honors Director ______________________________ Date WOMEN IN AVIATION 3 Abstract The Aviation industry has developed extensively since its establishment by the Wright Brothers in 1903. Over time, the highly male-dominated industry experienced significant changes to incorporate female aviators. Determined women initiated this process through participating in the aircraft engineering sector and pursuing careers as pilots. However, these women faced various challenges, which resulted in setbacks to their effective growth in the industry. In fact, vital issues encountered in the past are still present and often overlooked in today’s aviation industry. Therefore, identifying these problems and proposing solutions with effective corrective measures is necessary to increase and motivate female pilots globally. A time of consideration and re-evaluation is imminent. WOMEN IN AVIATION 4 Women in the Aviation Industry In the mid morning hours of December 17, 1903, a powered flying machine successfully took off, traveled one hundred and twenty feet in the air, and landed under the control of its pilot. Orville Wright’s twenty-two second flight initiated what would become an era of aerial transportation development in the United States and the world. -

River Oaks Residents Can Participate in the “Take Care of Texas” Pledge

Serving the City of River Oaks 79th Year No. 28 817-246-2473 7820 Wyatt Drive, Fort Worth, Texas 76108 suburban-newspapers.com July 11, 2019 Around the Town with Melody Dennis River Oaks Residents Can Participate in the “Take Care of Texas” Pledge You can type, TakeCareOfTexas.org in your computer or smart phone brows- er and the website will pop up. The Take Care of Texas Pledge is not just for water, but for the air we breathe, energy conservation, reducing waste and saving ourselves some money in the process. The website starts off with country music artist Cody Johnson sharing his music and his thoughts on a short commercial for taking care of the only Texas we have! After you watch the commercial, you can scroll down the page and see the “Take the Pledge” section, and simply click on the “Pledge” icon. It asks for your name, address and email. In return, you receive a free Texas Parks and Wildlife State Park Guide, along with a free Texas shaped sticker. I will be checking the mail daily in anticipation of my free guide and sticker. As you continue to scroll down the page, you can use a “waste calcula- As proud Texans, who wouldn’t want to take care of our beloved state? tor” which tells you how much waste you have created starting from your Texas is so popular right now that approximately 1,000 people per day move birth year, learn about visiting some cool Texas caves, use online calculators to this state. Half of those are adults from other states and a long list of for- for water, energy, and ways for saving money and get tips on how to maintain eign countries.