Sanjo in the 21St Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Korean Dance and Pansori in D.C.: Interactions with Others, the Body, and Collective Memory at a Korean Performing Arts Studio

ABSTRACT Title of Document: KOREAN DANCE AND PANSORI IN D.C.: INTERACTIONS WITH OTHERS, THE BODY, AND COLLECTIVE MEMORY AT A KOREAN PERFORMING ARTS STUDIO Lauren Rebecca Ash-Morgan, M.A., 2009 Directed By: Professor Robert C. Provine School of Music This thesis is the result of seventeen months’ field work as a dance and pansori student at the Washington Korean Dance Company studio. It examines the studio experience, focusing on three levels of interaction. First, I describe participants’ interactions with each other, which create a strong studio community and a women’s “Korean space” at the intersection of culturally hybrid lives. Second, I examine interactions with the physical challenges presented by these arts and explain the satisfaction that these challenges can generate using Csikszentmihalyi’s theory of “optimal experience” or “flow.” Third, I examine interactions with discourse on the meanings and histories of these arts. I suggest that participants can find deeper significance in performing these arts as a result of this discourse, forming intellectual and emotional bonds to imagined people of the past and present. Finally, I explain how all these levels of interaction can foster in the participant an increasingly rich and complex identity. KOREAN DANCE AND PANSORI IN D.C.: INTERACTIONS WITH OTHERS, THE BODY, AND COLLECTIVE MEMORY AT A KOREAN PERFORMING ARTS STUDIO By Lauren Rebecca Ash-Morgan Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2009 Advisory Committee: Dr. Robert C. Provine, Chair Dr. -

Playing Janggu (Korean Drum)

2011 EPIK Episode 1 Playing Janggu (Korean drum) Written by: Jennifer Arzadon Cheongju Technical High School The most impressive moment that has happened to me at my school would have to be when I accidentally joined the samul nori teacher’s group. I was invited to be a spectator at a samul nori practice session during lunchtime. The moment I entered their practice room, a janggu was placed in front of me and I was shown how to beat the drum-like instrument. Samul nori is the Korean traditional percussion music. The word samul means "four objects" and nori means "play" which is performed with four traditional Korean musical instruments: kkwaenggwari (a small gong), jing (a larger gong), janggu (an hourglass-shaped drum), and buk (a barrel drum similar to the bass drum). The traditional Korean instruments are called pungmul. Every Monday during lunchtime is our regular practices. Our leader kindly gave me my own gungchae and yeolchae so I can practice playing janggu on my own. One month later, we were told that the samul nori team was to perform for the official opening of the school’s new building. The week before the performance, we met and practiced every day during lunch along with the students who were going to perform with us. The day finally came for our first performance and I was pretty nervous. We got dressed in the traditional samul nori outfits and practiced one last time before heading out. The performance went great. We performed in front and all around the building to bless, to ensure good fortune and of course to celebrate. -

Asean-Korea Festival 2014

PRASAT BAYON Angkor Thom, Angkor, Siem Reap Province Kingdom of Cambodia PROGRAM SIEM REAP PRASAT BAYON MARCH 19 (WED), 2014 18:30-20:30 CAMBODIAN PERFORMANCE SARANG-GA Cambodia Traditional Performance Traditional Song & Dance BUCHAE-CHUM JINDO BUK-CHUM Traditional Dance Traditional Dance SONGS OF ARIRANG KOREAN DRAMA OST Traditional Folk Music Music From ‘City Hunter’ & ‘King of Baking, Kim Tak Goo’ YEOKDONG NONGAK-MU Choreographed Dance Traditional Dance JANGGU-CHUM Traditional Dance ASEAN-KOREA FESTIVAL 2014 CAMBODIA PRASAT BAYON, SIEM REAP 18:30-20:30 MARCH 19 WWW.ASEANKOREA.ORG blog.aseankorea.org 8F, Sejong-daero 124 www.facebook.com/ASEANROKcentre Jung-gu, Seoul www.twitter.com/ASEANROKcentre EMBASSY OF THE REPUBLIC OF KOREA CO-ORGANIZED BY MINISTRY OF TOURISM SUPPORTED BY Republic of Korea, 100-750 www.youtube.com/user/ASEANROKcentre IN THE KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA ASEAN-KOREA FESTIVAL 2014 IN CAMBODIA PERFORMANCES ABOUT ASEAN-KOREAN FESTIVAL 2014 BUCHAE-CHUM | TRADITIONAL DANCE JANGGU-CHUM | TRADITIONAL DANCE SONGS OF ARIRANG ASEAN-Korea Festival 2014 is co-organized by the ASEAN-Korea Centre and The simple yet graceful movement of Jukseon Janggu-chum is a rhythmic piece, where A compilation of different versions of Arirang such as, the Ministry of Tourism in the Kingdom of Cambodia and supported by (traditional fan made out of bamboo shoot) and female dancers play various beats with Gein Arirang, Jungsun Arirang, Gu Arirang, Bonjo Arirang, Gangwondo the Embassy of the Republic of Korea in the Kingdom of Cambodia. This cultural Hanji (traditional Korean paper handmade from the Janggu (traditional Korean drum) Arirang, Haeju Arirang and Miryang Arirang will be performed in event is part of an effort to celebrate the 25th Anniversary of Dialogue Partnership mulberry trees) is like seeing a fully bloomed slung over their waist while tiptoeing Sori (Korean word referring to the traditional way of singing). -

Programme Booklet

Contents Forewords & Messages 1. Welcoming Messages p.4 2. About APSMER (Asia-Pacific Symposium for Music Education Research) p9 3. Organizing Committee of APSMER2019 p10 4. About MPI’s Music Program p11 5. About ISME World Conference 2020 p12 6. MPI Campus Map p13 Program 7. Rundown p14 8. Detail Program p16 9. Keynote Speech p23 10. ISME Open Session p26 11. Program of Welcome Concert p27 12. Performing Groups p29 Acknowledgements 13. Students Volunteers p35 14. Supporting Partners p36 Astracts p40 ] 3 [ Speech at the Opening Ceremony of the 12th Asia-Pacific Symposium for Music Education Research Prof. Im Sio Kei President of Macao Polytechnic Institute 2019.07.16 Distinguished guests, Ladies and Gentlemen, On behalf of the Macao Polytechnic Institute, I would like to welcome you to the “12th Asia-Pacific Symposium for Music Education Research”! On the occasion of the 20th anniversary of Macao’s returning to the motherland, we are honoured to organise this international event in the music education industry. Culture and education have always been one of the key directions of Macao well supported by the Government. Art education is a key foundation for cultural development. Music, as an important measure of art education, plays a considerable role in developing students’ personality, culture, and sentiment. Deeply aware of the importance of music education, Macao Polytechnic Institute, as the only higher education institution in Macao that simultaneously offers music, design and visual arts, has always been committed to educating music professional artists and music educators who serve Macao. On the basis of the review of the UK Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education, the Bachelor of Arts in Music programme has also been accredited by the Higher Education Evaluation and Accreditation Council of Taiwan. -

A Comparative Study of Selected Secondary School Preservice Music Teacher Education Programs in the Republic of Korea And

A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF SELECTED SECONDARY SCHOOL PRESERVICE MUSIC TEACHER EDUCATION PROGRAMS IN THE REPUBLIC OF KOREA AND THE UNITED STATES by Bo Yeon Kim A dissertation submitted to the faculty of The University of Utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Music The University of Utah December 2015 Copyright © Bo Yeon Kim 2015 All Rights Reserved The University of Utah Graduate School STATEMENT OF DISSERTATION APPROVAL The dissertation of Bo Yeon Kim has been approved by the following supervisory committee members: Mark Ely , Chair 03/13/2015 Date Approved Joelle Lien , Member 03/13/2015 Date Approved Rachel Nardo , Member 03/13/2105 Date Approved Hasse Borup , Member 03/13/2015 Date Approved Michael Gardner , Member 03/13/2015 Date Approved and by Miguel Chuaqui , Chair/Dean of the Department/College/School of Music and by David B. Kieda, Dean of The Graduate School. ABSTRACT In this study, I investigated and compared secondary school preservice music teacher education programs in the Republic of Korea and in the United States of America. The purpose of this study was to identify similarities and differences between secondary school preservice music teacher education programs from Korea and the United States to facilitate understanding of teacher education programs. I analyzed in detail the admission requirements, curricula, and teaching practica of selected universities in both countries. Specifically, four Korean universities and three U.S. universities were selected for analysis. The Korean universities were Chonnam National University [CNU], Kongju National University [KNU], Korea National University of Education [KNUE], and Konkuk University [KU]. -

Korean Drumming and Creative Music Virtual Performance Program Here

Korean Drumming & Creative Music A Virtual Performance Wednesday, May 5, 2021 World Music Hall, Wesleyan University Program Beginning and advanced students of the Korean Drumming Ensemble & Creative Music, directed by Adjunct Assistant Professor of Music Jin Hi Kim, play pieces derived from tradition in addition to new ideas, performed on the two-headed drums 장구(janggu), barrel drums 북(buk), hand gong 꽹과리(kwenggari), and a suspended gong 징(jing). The group plays a variety of mesmerizing janggo rhythmic patterns, which swing through innumerable repetitive cycles and get dramatically and vigorously developed. The ensemble also creates new work discovering new possible sounds and imaginative explorations on those instruments. The ensemble has spent the past semester learning about the instruments, practices, and cultural implications that galvanize to shape the music and culture of Korean drumming. Throughout the course, students were asked to consider not only the music’s sound, but also it's physical forms. They learned to explore the historical context associated with each instrument. For example, the two-headed janggu drum symbolizes yin and yang, which is reflected in the characteristics of sound and energy. Students focus on their individual drumming as a meditative practice, but they also learn to work collaboratively as a united and respectful group. They have cultivated calm and confident energy for three months. In the end they integrate their focused mind, physical body energy and breathing through a stream of repetitive rhythmic cycles. They are mesmerized by the repetition. Students have expressed that they learned joy, meditation, relaxation, creativity, social community, and the satisfaction of being one voice through a team effort. -

The Emergence Of

田中理恵子 Rieko TANAKA Between Art and Anthropology: The Emergence of ‘Border’ in the Musical Communication ●抄録 Folk music has recently crossed the border of its original local position where it has been situated and is diffusing into the world as a world soundscape. This article focuses on this characteristic and clarifies a part of its transborder–communication in a sense that it is handed down for generations and at the same time that it spreads all over the world with an example of Pungmul, Korean folk music. Firstly, I took critically arguments on orality as a research realm of world of music. In folk music, which is handed down for and beyond generations by the oral tradition, orality is regarded not only as a transferability of the information by verbal communication but also as a mode of communication to which succeeds techniques and memories. Moreover, I pointed out that it was necessary to focus on the coordinating aspects of body as a medium and physical movements as conditions that make transmission possible. Secondly, with such a view this article focuses on the succession process that the transmission aspect of Pungmul music is easy to be shown, analyzing it from a point of each view of the successors, canons of music, instructors. The succession process in general is likely to be thought that it is just a process of imitation and repetition. In fact, however, it can be clearly seen that it is an intensive and indeterminate communication that the successors seek for the canons shown by the instructors or the ‘border’ between good or bad as a judgement, making use of the coordination of body and all the nervous systems as a reference point. -

Expreance Korean.Indd

GREETINGS Welcome to Experience Korea!!! The National Association for Korean Schools (NAKS) is pleased to off er you to experience Ko- rea while interacting with many Korean language school teachers. Please continue your experience and connect to Korea by attending activities of Ko- rean language schools in your area. When it comes to Experience Korea, NAKS and its member schools Seungmin Lee are here to give you the unique opportunity. Please enjoy. NAKS President Korean Wave (한류) The Korean Wave (Hangul: 한류; Hanja: 韓流; RR: Hallyu; MR: Hallyu, About this sound listen (help·info), a neologism literally meaning “fl ow of Korea”) is the increase in global popularity of South Korean culture since the 1990s First driven by the spread of K-dramas and K-pop across East, South and Southeast Asia during its initial stages, the Korean Wave evolved from a regional development into a global phenomenon, carried by the Internet and social media and the proliferation of K-pop music videos on YouTube.Part of the success of the Korean Wave owes in part to the development of social net- working services and online video sharing platforms such as YouTube, which have allowed the Korean entertainment industry to reach a sizable overseas audience. Since the turn of the 21st century, South Korea has emerged as a major exporter of popular culture and tourism, aspects which have become a signif- icant part of its burgeoning economy. The growing popularity of Korean pop culture in many parts of the world has prompted the South Korean govern- ment to support its creative industries through subsidies and funding for start- ups, as a form of soft power and in its aim of becoming one of the world’s leading exporters of culture along with Japanese and British culture, a niche that the United States has dominated for nearly a century. -

The Development of a Teachers' Pedagogical Guidebook Based On

The development of a teachers’ pedagogical guidebook based on Dalcroze Eurhythmics for teaching multicultural music lessons in the elementary schools of South Korea Thèse Hae Eun Shin Doctorat en musique Philosophiæ doctor (Ph. D.) Québec, Canada © Hae Eun Shin, 2021 RÉSUMÉ En Corée du sud, l’éducation musicale multiculturelle fait partie des programmes d’études de l’école primaire et les manuels scolaires comportent des répertoires d’exemples musicaux provenant de diverses régions du monde. Pourtant, malgré la place accordée à l’éducation multiculturelle dans les programmes scolaires, un certain nombre d'études ont soulevé la nécessité de méthodes d'enseignement favorisant chez l’élève une réelle compréhension de la musique en tant que culture. Ces recherches soulignent que les activités musicales proposées aux élèves doivent leur permettre de vivre des expériences musicales qui ne dissocient pas les musiques du monde de leur contexte culturel. Elles considèrent également que ces expériences musicales doivent être incarnées, vécues corporellement — à l’image des pratiques musicales du monde — et faire appel à la participation active de l’élève. La présente recherche, qui vise l’élaboration d’un guide pédagogique pour l’enseignement multiculturel de la musique dans les écoles primaires de la Corée du sud, s’appuie sur la rythmique Jaques-Dalcroze. Jaques-Dalcroze considère que le lien puissant qui existe entre la musique et les êtres humains est ancré dans la nature même du rythme qui est intrinsèquement lié au mouvement corporel. Cette approche pédagogique musicale, centrée sur l’expérience de l’élève et son interaction avec les autres, contribue à la découverte de soi et de l’autre; elle s’avère propice à l’appropriation de sa propre culture musicale et des diverses cultures musicales du monde. -

Coexistence of Classical Music and Gugak in Korean Culture1

International Journal of Korean Humanities and Social Sciences Vol. 5/2019 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14746/kr.2019.05.05 COEXISTENCE OF CLASSICAL MUSIC AND GUGAK IN KOREAN CULTURE1 SO HYUN PARK, M.A. Conservatory Orchestra Instructor, Korean Bible University (한국성서대학교) Nowon-gu, Seoul, South Korea [email protected] ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7848-2674 Abstract: Classical music and Korean traditional music ‘Gugak’ in Korean culture try various ways such as creating new music and culture through mutual interchange and fusion for coexistence. The purpose of this study is to investigate the present status of Classical music in Korea that has not been 200 years old during the flowering period and the Japanese colonial period, and the classification of Korean traditional music and musical instruments, and to examine the preservation and succession of traditional Gugak, new 1 This study is based on the presentation of the 6th international Conference on Korean Humanities and Social Sciences, which is a separate session of The 1st Asian Congress, co-organized by Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznan, Poland and King Sejong Institute from July 13th to 15th in 2018. So Hyun PARK: Coexistence of Classical Music and Gugak… Korean traditional music and fusion Korean traditional music. Finally, it is exemplified that Gugak and Classical music can converge and coexist in various collaborations based on the institutional help of the nation. In conclusion, Classical music and Korean traditional music try to create synergy between them in Korean culture by making various efforts such as new attempts and conservation. Key words: Korean Traditional Music; Gugak; Classical Music; Culture Coexistence. -

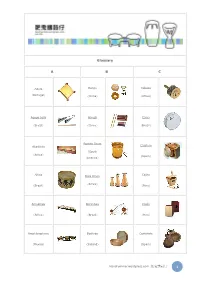

Handrummer.Wordpress.Com 肥鬼講鼓仔 Glossary A

Glossary A B C Adufe Bangu Cabasa (Portugal) (China) (Africa) Agogo bells Bangzi Caixa (Brazil) (China) (Brazil) Bombo Drum Cajatom Akadinda (South (Africa) (Spain) America) Alfaia Cajita Batá Drum (Africa) (Brazil) (Peru) Amadinda Berimbau Cajón (Africa) (Brazil) (Peru) Amphibiaphone Bodhran Castanets (Mexico) (Ireland) (Spain) Handrummer.wordpress.com 肥鬼講鼓仔 1 A B C Angklung Bodu Beru Caxixi (Indonesia) (Maldives) (Brazil) Apitua Bell Bongo Chimpta (Africa) (Brazil) (India) Boomwhacker Chinchinero Array Mbira (USA) (Chile) Arumukhanam Brekete Chocalho (India) (Africa) (Brazil) Atabaque Clave (Brazil) (Cuba) Cluster Drum (USA) Conga (Cuba) Cowbell Cuíca (Brazil) Handrummer.wordpress.com 肥鬼講鼓仔 2 D E F Dagu Empuunyi Flexatone (China) (Africa) (Britain) Fontomfrom Daouli Drum Enbuutu Ensemble (Greece) (Africa) (Africa) Djembe Engalabi (Africa) (Africa) Djundjun Ewe Family (Africa) (Africa) Doumbek (Middle East) Drumset (USA) The Dube G H I Hang Ipu Heke Galaxy (Switzerland) (Hawaii) Handrummer.wordpress.com 肥鬼講鼓仔 3 G H I Ipu Heke ‘Ole Gankoqui Helix Bowl (Africa) (Hawaii) Ganza Huehuetl (Brazil) (Mexico) Garrahand Drum (Argentina) Ghatam (India) Ginga Shaker (Brazil) Goat Toes Rattle (Africa) Guiro (Brazil) J K L Janggu Kalimba Liso Shaker (Africa) (Korea) Handrummer.wordpress.com 肥鬼講鼓仔 4 J K L Karkabou Liquid Triangle (Morocco) Kashaka Log Drum (Africa) (Africa) Kayamba (Africa) Kendang (Indonesia) Kisoga Embaire (Africa) Klong Yao (Thailand) Kokiriko (Japan) Kpanlogo (Africa) Handrummer.wordpress.com 肥鬼講鼓仔 5 J K L Kundu Drum (Papua New -

PROBES #22.2 Devoted to Exploring the Complex Map of Sound Art from Different Points of View Organised in Curatorial Series

Curatorial > PROBES With this section, RWM continues a line of programmes PROBES #22.2 devoted to exploring the complex map of sound art from different points of view organised in curatorial series. Auxiliaries PROBES takes Marshall McLuhan’s conceptual The PROBES Auxiliaries collect materials related to each episode that try to give contrapositions as a starting point to analyse and expose the a broader – and more immediate – impression of the field. They are a scan, not a search for a new sonic language made urgent after the deep listening vehicle; an indication of what further investigation might uncover collapse of tonality in the twentieth century. The series looks and, for that reason, most are edited snapshots of longer pieces. We have tried to at the many probes and experiments that were launched in light the corners as well as the central arena, and to not privilege so-called the last century in search of new musical resources, and a serious over so-called popular genres. In this auxiliary the world’s instruments get new aesthetic; for ways to make music adequate to a world stirred into ever more varieties of nutritious musical soup. Do not boil! transformed by disorientating technologies. Curated by Chris Cutler 01. Playlist 00:00 Gregorio Paniagua, ‘Anakrousis’, 1978 PDF Contents: 01. Playlist 00:06 Peter Sculthorpe in Memoriam Broadcast, ABC Radio (excerpt), 2014 02. Notes Peter Sculthorpe was an Australian composer who always took a particular 03. Links interest in the music of Australia's Asian neighbours and, increasingly, in the 04. Credits and acknowledgments landscape and culture of the surviving indigenous population of his own country.