Promotio Iustitiae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Facultyhandbook

FACULTY HANDBOOK 2017-2018 COPYRIGHT: LOYOLA UNIVERSITY MARYLAND TABLE OF CONTENTS REMINDER CALENDAR* ........................................................................................................................................i INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................................... iii FACULTY HANDBOOK AND ACADEMIC POLICY COMMITTEE ..............................................................iv ON-LINE RESOURCES ............................................................................................................................................. v I. ORIGIN AND DEVELOPMENT OF LOYOLA UNIVERSITY MARYLAND ......................................... I-1 A. Purpose ......................................................................................................................................................... I-1 B. 1852-1917 .................................................................................................................................................... I-1 C. 1917-1950 .................................................................................................................................................... I-2 D. 1950-1964 .................................................................................................................................................... I-4 E. 1964 To 1993 .............................................................................................................................................. -

Please Carefully Read All of the Following Pages of the Loyola Parents’ and Students’ Handbook

Please carefully read all of the following pages of the Loyola Parents’ and Students’ Handbook. Parents and students are responsible and accountable for the information found in this document. After you have read the document, please return to this page and click each of the links to electronically sign each of the following documents. Parent/Student Handbook Agreement Form Media Release Form PARENTS’ AND STUDENTS’ HANDBOOK 2017-2018 Mission, Vision, Values .....................................................1 Requirements for Graduation .........................................21 Graduate at Graduation ....................................................1 Academic Information .....................................................22 Administration/Faculty ......................................................3 Bell Schedules ................................................................29 Staff ..................................................................................5 Ministry Programs ...........................................................29 School Services ................................................................6 Community Service ........................................................31 Tuition ...............................................................................7 Counseling ......................................................................35 Financial Aid .....................................................................8 Student Activities ............................................................36 -

MONTREAL. AUTUMN 1963 VOL. VII. NO. 3 35Mm COLOUR SLIDES of LOYOLA COLLEGE October 19Th, Saturday - CAMPUS and AREA

MONTREAL. AUTUMN 1963 VOL. VII. NO. 3 35mm COLOUR SLIDES OF LOYOLA COLLEGE October 19th, Saturday - CAMPUS AND AREA. 'AT HOME' On campus day program and dinner-dance at Ritz-Carlton Hotel in evening. The Alumni Association and the c o 11 e g e are (See page l O for details) preparing to produce an up-to-date story of Loyola Co 11 e g e through this November 1, 2, 3, Friday to Sunday - medium. Closed RETREAT at Monreso. We believe many people have taken 35mm colour November 15th, Friday - slide pictures which would be most helpful to us in OYSTER PARTY. this project. Would you please lend CLASS REUNIONS or donate slides you have taken of Loyola over the past years. We will be Closs '38, '41, and '53 will be holding stag parties on Friday, sure to return them if you October 18th and attending 'At Home' day functions on campus so desire. and the dinner-dance Saturday evening, the 19th . .. .the best-tasting _filter cigarette CONTENTS Vol. VII No. 3 LOYOLA ALU MN I ASSOCIATION HARRY J. HEMENS, Q.C., '32 President DONALD W. McNAUGHTON, '49 1st Vice-President ROSS W. HUTCHINGS, '45 Page 2nd Vice-President 2 Editorial : The Articulate In College J. DONALD TOBIN, '36 3 Who's Afraid of Moby Dick? 3rd Vice-President 4 New Professors ARCHIBALD J. MacDONALD, Q.C., '26 Honorary Secretary 5 Golf Tournament Maj. Gen. FRANK J. FLEURY, 6 Travel Overseas CBE, ED, CD, '34 8 lnsignus Ductu Et Rebus Gestis Honorary Treasurer 9 Profile KENNETH F. -

Name of the Institution District State Centurian Public School Rayagada

Name of the Institution District State Centurian Public School Rayagada Andhra Pradesh Navodaya Atchutarama E-techno School Vizianagram Andhra Pradesh Krishanveni Talent School Rajam Andhra Pradesh Sri Surya Vidyalam School, Kotarubilli Vizianagram Andhra Pradesh The Vision English Med. School, Gantyada Vizianagram Andhra Pradesh Sahiti Public School, B.t. Valasa Parvathipuram Andhra Pradesh St. Mary's Primary School, Vinukonda Guntur Andhra Pradesh Loyola High School, Vinukonda Guntur Andhra Pradesh Bhaskar Brilliant English Med. School Parvathipuram Andhra Pradesh Sacred Heart English Med. School Perechowk Andhra Pradesh Blesso Matriculation school Vellore Andhra Pradesh St. Dominic English Med. School, Palakonda Srikakulam Andhra Pradesh Panzanya High School, Vinukonda Guntur Andhra Pradesh Amirtham Primary & Nursery School Vellore Andhra Pradesh Seventh Day Matric School Vellore Andhra Pradesh Sangha Mitra High School Hyderabad Andhra Pradesh S.K.S.R.M.C.E.M. School Vjayawada Andhra Pradesh Sunil's English Med. School East Godavari Andhra Pradesh NMMC Urdu School Vijayawada Andhra Pradesh Smile Digi High School Hanumakonda Andhra Pradesh A.M.P.M.C. Elementary School Vijayawada Andhra Pradesh M.A.R.M.C. Elementary School Vijayawada Andhra Pradesh M.P.L. Corp. Elementary School Vijayawada Andhra Pradesh Mother Teresa English Med. School Vijayawada Andhra Pradesh Urdu Elementary School Vijayawada Andhra Pradesh Sunray School, Sivini Komarada Andhra Pradesh Vivekanand School, Kintali Mill Srikakulam Andhra Pradesh Brahm Prakash DAV School, Midhani Hyderabad Andhra Pradesh Army Public School Kunnoor Andhra Pradesh Vani Vidyalam, Navbharat Nagar Guntur Andhra Pradesh Kusuma Vidyalayam Tenali Andhra Pradesh Rajkumar College Raipur Chattisgarh Mata Sundari Public School, Chirmiri Raipur Chattisgarh Maria Hr. Sec. School, Chirmiri Korea Chattisgarh Rewa Coalfield English Med. -

2003-2004 Undergraduate Bulletin

Undergraduate Bulletin 2003-2004 2/ TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents University Phone Numbers . .3 Academic Calendar 2003-2004 . .4 The University . .7 University Facilities . .12 University Services . .16 Student Affairs . .21 Admission . .29 Financial Aid . .34 Tuition and Fees . .45 University Core Curriculum . .50 Academic Degrees and Programs . .54 Academic Degree Requirements and Policies . .58 Academic Programs and Services . .71 Academic Awards and Commencement Honors . .77 University Honors Program . .81 Bellarmine College of Liberal Arts . .84 College of Business Administration . .209 College of Communication and Fine Arts . .236 College of Science and Engineering . .288 School of Education . .379 School of Film and Television . .400 Department of Aerospace Studies . .426 Campus Maps . .429 University Administration . .434 University Faculty . .438 Index . .458 UNIVERSITY PHONE NUMBERS / 3 University Phone Numbers Westchester Campus Offices: Mailing Addresses: Area Code is 310 LOYOLA MARYMOUNT UNIVERSITY One LMU Drive Academic Vice President . .338-2733 Los Angeles, California 90045 (310) 338-2700 Admissions, Graduate . .338-2721 http://www.lmu.edu/ Admissions, Undergraduate . .338-2750 Alumni Relations . .338-3065 LOYOLA LAW SCHOOL 919 South Albany Street Bellarmine College of Liberal Arts . .338-2716 P.O. Box 15019 Campus Ministry . .338-2860 Los Angeles, California 90015-0019 (213) 736-1000 Chancellor’s Office . .338-3070 http://www.lls.edu/ College of Business Administration . .338-2731 College of Communication and Fine Arts . .338-7430 College of Science and Engineering . .338-2834 Controller’s Office . .338-2711 Development Office . .338-7545 Financial Aid Office . .338-2753 Information . .338-2700 Jesuit Community Residence . .338-7445 Library . .338-2788 LMU Extension . .338-2757 Operations and Maintenance . -

2011-2012 School Profile

2011-2012 School Profile HISTORY In 1852, Archbishop Francis Kenric of Baltimore asked the members of the Society of Jesus to oversee the formation of a school for laymen that would incorporate standards of excellence and build new men, conscious of a religious purpose. The construction of Loyola High School began on Calvert Street in early 1852 and on September 15, the doors opened. In 1941, the school relocated to Blakefield in Towson, Maryland. Between 1981-1988, a Middle School was gradually introduced and Loyola officially became known as Loyola Blakefield. Loyola typically enrolls 1000 students, with 750 students in grades 9-12. TYPE: Catholic, Jesuit, Private School for boys in grades 6-12 MISSION: The mission of Loyola Blakefield is to graduate young “men for others” who are open to growth, dedicated to academic excellence, religious, loving, committed to diversity and dedicated to work for a just world. The philosophy of the school is to provide each student with careful and thoughtful teaching, cura personalis—personal care of the individual, and motivation in a spiritual environment. LOCATION: 500 Chestnut Avenue, Towson, MD, 21204. Towson is a northern suburb of the city of Baltimore. ACCREDITATION: Association of Independent Maryland Schools MEMBERSHIPS: Jesuit Secondary Educational Association; Association of Maryland Independent Schools; National Association of College Admissions Counselors, Potomac and Chesapeake Association of College Admissions Counselors, College Board. SCHOLARSHIP + Scholarship and Financial Aid are available. Currently, 27% of the student population receives scholarship or financial FINANCIAL AID: aid. FACULTY: Loyola Blakefield has a professional faculty and staff of approximately 100 men and women, two-thirds of whom hold advanced degrees and one-third of whom have taught at the school for more than fifteen years. -

2009-2010 School Profile

2009-2010 School Profile HISTORY In 1852, Archbishop Francis Kenric of Baltimore asked the members of the Society of Jesus to oversee the formation of a school for laymen that would incorporate standards of excellence and build new men, conscious of a religious purpose. The construction of Loyola High School began on Calvert Street in early 1852 and on September 15, the doors opened. In 1941, the school relocated to Blakefield in Towson, Maryland. Between 1981-1988, a Middle School was gradually introduced and Loyola officially became known as Loyola Blakefield. Loyola typically enrolls 1000 students, with 750 students in grades 9-12. TYPE: Catholic, Jesuit, Private School for boys in grades 6-12 MISSION: The mission of Loyola Blakefield is to graduate young ‘men for others’, who are open to growth, dedicated to academic excellence, religious, loving, committed to diversity and dedicated to work for a just world. The philosophy of the school is to provide each student with careful and thoughtful teaching, cura personalis—personal care of the individual, and motivation in a spiritual environment. LocatioN: 500 Chestnut Avenue, Towson, MD, 21204. Towson is a northern suburb of the city of Baltimore. ACCREditatioN: Association of Independent Maryland Schools MEMBERSHIPS: Jesuit Secondary Educational Association; Association of Maryland Independent Schools; National Association of College Admissions Counselors, Potomac and Chesapeake Association of College Admissions Counselors, College Board. SCHOLARSHIP + Scholarship and Financial Aid are available. Currently, 27% of the student population receives scholarship or financial aid. FINANCIAL AID: FACUltY: Loyola Blakefield has a professional faculty and staff of approximately 100 men and women, two-thirds of whom hold advanced degrees and one-third of whom have taught at the school for more than fifteen years. -

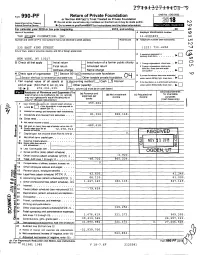

2018 Or Tax Year Beginning , 2018, and Endina Name of Foundation a Employer Ldentlf1catlon Number the PFJEER FOUNDATION, INC

Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation Department o,,t the Treasury ... Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Internal Revenue Service .,. Go to www.irs.gov/Fonn990PF for instructions and the latest information For ca endar vear 2018 or tax year beginning , 2018, and endina Name of foundation A Employer ldentlf1catlon number THE PFJEER FOUNDATION, INC. 13-6083839 Number and street (or PO box number 11 ma1l 1s not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see 1nstruct1ons) 235 EAST 42ND STREET ( 212) 733 -4250 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption appllcat1on 1s pending, check here. • • NEW YORK, NY 10017 G Check all that apply Initial return ,___ Initial return of a former public charity D 1 Foreign organ1zat1ons. check here. ,___ Final return ~ Amended return 2 F ore1gn orgamzat1ons meeting the 85% test, check here and attach Address change Name change computat1on • • • • • • • • H Check type of organization X Section 501 (c)(3) exempt private foundation oy E If private foundation status was terminated D _.___.n __S.::.e.::.c::.:t::..:10:.:.n.:...4...:..::.94..;..7.:...'<:c:a:u..H1,_,, >...:n::..:o:..:n::..:e:::.x:.=e::..:m.:.,10:.:t....:c:.:.h:.=a::..:ri:.=ta:.:b:.:.le:;....::.tr.:::u.:::st:....__,_""._,_=O:.:t::..:h=e.:...r.:.ta=xa:;:=b:..::le;...c..:.:Pn.:.v::::ac:cte;....:.f.:::o.;:u::..:n.=d.=ac.::t1.:::o::..:n n ___ ..:__--l under section S07(b)(1)(A) check here . -

Andhra Vani September – 2020

NO: 451 NEWSLETTER OF ANDHRA JESUIT PROVINCE SEPTEMBER - 2020 The Pope's Monthly Intentions for September 2020: Respect for the Planet's Resources We pray that the planet's resources will not be plundered, but shared in a just and respectful manner INFORMATION Nativity of Blessed Virgin Mary Fr.General has appointed ANANDA JYOTHI, NAMBUR: Fr. Keith William day celebration of our Founder Father St. Ignatius of Abranches, SJ as Rector On 31st July, we had a simple but meaningful feast of Collegio Internazionale, Gesu, from July 2021. ‘new-scholastics’, novices, Jesuits, and a few sisters. It was profound, yetLoyola. simple On thisEucharistic special occasion celebration our chapelin the wasretreat filled house with followedthe by a sumptuous dinner. We are immensely happy for the safe arrival of Fr C. Alex SJ Fr Dionysius Gerard on 6th August. Fr Thambi took all the scholastics for shopping to buy necessary Leonard Vaz (Dion), SJ as provincial of Karnataka goods. Our new-scholastics are blazing Jesuit Province. efforts to improve their English language. We had blissful occasions to wish two of our New cell number of scholastics, P. Sathish and Madhan as they Fr. A. John Joseph SJ celebrated their birthdays in this month. 6281321270 On 15th Aug., we celebrated with delightful PROVINCIAL'S feeling, our 74th Independence Day. Novice PROGRAMME - Velangani delivered the Independent Day SEPTEMBER 2020 Speech. We honoured our national flag and isremembered getting ready the to incredible begin a ‘Monthsacrifices long of 08 - Laying of foundation our freedom fighters. The Retreat House stone for YES-J center & congregations under the guidance of Fr Final vows of Amalanathan.Retreat’ for five May sisters God from bless two the different efforts Fr. -

AWS Educate Instituion List

Educate Institution City Country 3aaa Apprenticeships Derby United Kingdom 3W Academy Paris France A P Shah Institute of Technology Thane West India A.V.C. College of Engineering Mayiladuthurai India AARHUS TECH Aarhus N Denmark Aarupadai Veedu Institute of Technology Kanchipuram(Dt) India Abb Industrigymansium Västerås Sweden Abertay University Dundee United Kingdom ABES Engineering College Ghaziabad India Abilene Christian University Abilene United States ABMSP's Anantrao Pawar College of Engineering and Pune India Research Pune Abo Akademi University Turku Finland Academia de Bellas Artes Semillas Ltda Bogota Colombia Academia Desafio Latam Santiago Chile Academie Informatique Quebec-Canada Lévis Canada Academy College Bloomington United States Academy for Urban Scholars Columbus United States ACAMICA Palermo Argentina Accademia di Belle Arti di Cuneo Cuneo Italy Achariya College of Engineering Technology Puducherry India Acharya Institute of Technology Bangalore India Acharya Narendra Dev College New Delhi India Achievement House Cyber Charter School Exton United States Acropolis Institute of Technology & Research, Indore Indore India Educate Institution City Country Ada Developers Academy Seattle United States Ada. National College for Digital Skills London United Kingdom Additional Skill Acquisition Programme (ASAP) Thiruvananthapuram India Adhi college of Engineering and Technology KAncheepuram India Adhiyamaan College of Engineering Hosur India Adithya Institute of Technology coimbatore India Aditya Engineering College Kakinada -

Two Works, One Spirit

Social Justice and Ecology Secretariat of the Society of Jesus ENG February 2018 ...to exchange social justice and ecology news, stimulate contacts, share spirituality and promote networking... Narrative Two works, one spirit Moritz Kuhlmann SJ (GER) "Try to engage our students in a social project!" says Father Axel Bödefeld SJ, the headmaster of Loyola gymnasium. He has this wish for the students of Loyola gymnasium, which is considered the best school in Kosovo. Ignatian pedagogy however aims at more than best results in comparative tests. He wants the elite students to receive an education for their hearts as well. Saide gets 15 Cents for a kilogram of scrap metal. The old woman dropped her wheelbarrow on the side of the street. In a dirty puddle, she was washing her face. She introduced me to her neighborhood, to every house and family. I find myself in the Roma quarter 'Tranzit', next to the highway. Here I want to take the Loyola students. Loyola High School and Tranzit are two extreme worlds. On one hand the sharp looking EU- colored uniforms, worn by Albanians of good families, on the other hand ratty street clothes with muddy boots, worn by Roma children of poor houses. Albanians claim that Roma during the Kosovo war in 1999 were fighting alongside the Serbs against Albanians. In order to escape the hatred, many deny their identity as Roma and call themselves Ashkali. Will it be possible to build a bridge between the two worlds? Loyola can bring education, uplift, recognition to Tranzit. But Tranzit can help Loyola and its students too, with a more responsible and reconciled life, with a deep formation of personality. -

Schools for Class-VIII in All Districts of Jharkhand State School CODE UDISE NAME of SCHOOL

Schools for Class-VIII in All Districts of Jharkhand State School CODE UDISE NAME OF SCHOOL District: RANCHI 80100510 20140117617 A G CHURCH HIGH SCHOOL RANCHI 80100376 20140105605 A G CHURCH MIDDLE SCHOOL KANKE HUSIR 80100383 20140106203 A G CHURCH SCHOOL FURHURA TOLI 80100806 20140903803 A G CHURCH SCHOOL 80100917 20140207821 A P E G RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL RATU 80100808 20140904002 A Q ANSARI URDU MIDDLE SCHOOL IRBA 80100523 20140119912 A S PUBLIC SCHOOL 80100524 20140120009 A S T V S ZILA SCHOOL 80100411 20140109003 A V K S H S 80100299 20140306614 AADARSH GRAMIN PUBLIC SCHOOL TANGAR 80100824 20140906303 ADARSH BHARTI PUBLIC HIGH SCHOOL MANDRO 80100578 20142401811 ADARSH H S MCCLUSKIEGANJ 80100570 20142400503 ADARSH HIGH SCHOOL SANTI NAGAR KHALARI 80100682 20142203709 ADARSH HIGH SCHOOL KOLAMBI TUSMU 80100956 20141108209 ADARSH UCHCHA VIDYALAYA MURI 80100504 20140116916 ADARSHA VIDYA MANDIR 80100846 20140913601 ADARSHHIGH SCHOOL PANCHA 80100214 20140603012 ADIVASI BAL VIKAS VIDYALAYA JINJO THAKUR GAON 80100911 20140207814 ADIVASI BAL VIKAS VIDYALAYA RATU 80100894 20140202702 ADIVASI BAL VIKAS VIDYALAYA TIGRA GURU RATU 80100119 20140704204 ADIVASI BAL VIKAS VIDYALAYA TUTLO NARKOPI 80100647 20140404507 ADIWASI VIKAS HIGH SCHOOL BAJRA 80101106 20140113028 AFAQUE ACADEMY 80100352 20140100813 AHMAD ALI MORDEN HIGH SCHOOL 80100558 20140123620 AL-HERA PUBLIC SCHOOL 80100685 20142203716 AL-KAMAL PLAY HIGH SCHOOL 80100332 20142303514 ALKAUSAR GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL ITKI RANCHI 80100741 20140803807 AMAR JYOTI MIDDLE CUM HIGH SCHOOL HARDAG 80100651 20140404516