Howtosurvivethetitanic 9780062

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Survive the Titanic Or the Sinking of J. Bruce Ismay Free

FREE HOW TO SURVIVE THE TITANIC OR THE SINKING OF J. BRUCE ISMAY PDF Frances Wilson | 352 pages | 14 Mar 2012 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781408828151 | English | London, United Kingdom The Life of Bruce Ismay After Titanic’s Sinking – Part Two How to Survive the Titanic. Or The Sinking of J. Bruce Ismay Frances Wilson, Bloomsbury. Frances Wilson invokes Herman Melville to compare Ismay to Captain Ahab and even to Noah in this often ludicrous bookbut predominantly plumps for Joseph Conrad in her meditation on the life - and the elemental living - of this single individual, in whom is seemingly forever embarked the fate of fifteen hundred. The first syllable asserts enduring existence, the second an implication of twin alternatives. Ismay lived, and his reputation died. Had he not entered collapsible C it is scarcely imaginable that anyone would have branded him a coward. Instead mere mortality would have conferred its very opposite, in the palpable vein of an Isidor Straus or any other drowned potentate of the merchant classes. But such is a preserved-in-amber afterlife. With Ismay, though he now be dead, we can still poke the wounds. And so Wilson, as sanguinary soothsayer, enters into her very own launch — because this is a commercial voyage, complete with the richly absurd sales claim that Ismay fell in love with a married passenger on the maiden voyage. He did no such thing. It is as well that this work is largely a meditation — albeit with some interesting photographs and detail provided by the Cheape family — as the author seems only rudimentarily acquainted with the Titanic story. -

Chronology – Sinking of S.S. TITANIC Prepared By: David G

Chronology – Sinking of S.S. TITANIC Prepared By: David G. Brown © Copyright 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009 by David G. Brown; All rights reserved including electronic storage and reproduction. Registered members of the Encyclopedia-Titanica web site may make a one (1) copy for their own use; and may reproduce short sections of this document in scholarly research articles at no cost, providing that credit is given to the “Brown Chronology.” All other use of this chronology without the expressed, written consent of David G. Brown, the copyright holder is strictly forbidden. Persons who use this chronology are expected to assist with corrections and updates to the material. Last Updated June 9, 2009 New York Time = Greenwich (GMT) – 5:00 Assumed April 14th Hours (Noon Long 44 30 W) Titanic = Greenwich – 2:58 Titanic = New York + 2:02 Assumed April 15th Hours (Noon Long 56 15 W) Titanic = Greenwich – 3:45 Titanic = New York + 1:15 Bridge Time (Bells) = Apri 14th Hours + 24 minutes; or, April 15th Hours - 23 minutes (Bridge time primarily served the seamen to allow keeping track of their watches by the ringing of ship’s bells every half hour.) CAUTION: Times Presented In This Chronology Are Approximations Made To The Best Of The Author’s Ability. Times Presented In This Chronology Have An Assumed Accuracy Range Of Plus-Or-Minus 10 Percent, or 6 Minutes either side of the time shown (total range 12 minutes). NOTES Colors of Type: BLACK – Indicates actions and events in the operation of the ship or the professional crew. -

![Basketgs [Converted]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0387/basketgs-converted-2460387.webp)

Basketgs [Converted]

November/December 2010 The Newsletter of The Society Hill Civic Association SOCIETY HILL Reporter www.societyhillcivic.org National Museum of American Jewish History Opens This Month very exciting Society Hill Civic Association The new Museum’s core exhibition explores A (SHCA) program is planned for our General the challenges faced by Jews since their arrival Membership Meeting on Wednesday evening, on this continent in 1654. According to Mr. November 17th. Our invited speaker, Michael Rosen zweig, “The exhibition celebrates Jewish Rosenzweig, is the President and CEO of the experiences in every facet of American life and new National Museum of American Jewish throughout every phase of the country’s history.” History — located on Independence Mall. Just Featuring more than 1,000 artifacts, as well as three days after its Grand Opening Weekend, films and state-of-the-art technology, the exhibits November 12th-14th, Mr. Rosenzweig will give showcase how an immigrant population flour- our civic association anenlightening presentation. ished under freedom — highlighting the diverse Michael Rosenzweig, backgrounds and experiences of Jews over President and CEO of The Museum — a Smithsonian Affiliate — a period of more than 350 years. The exhibits the magnificent new will open to the public on Friday, November National Museum of are, of course, “family friendly,” with hands-on 26th. It will be a powerful testament to what all American Jewish History activities and lessons appropriate for all age free people can accomplish for themselves and groups — as they were assembled by a team for society at large. Standing directly across from of leading historians of American Jewish history. -

Le Comportement D'ismay

Le comportement d’Ismay. Philippe Chevalier. Le comportement de J. Bruce Ismay à bord du Titanic a fait polémique. La principale accusation portée à son égard est qu’il ait survécu, alors que quinze cents personnes ont perdu la vie dans le naufrage. D’un point de vue moral, c’est une abomination. Mais peut-on, cent ans plus tard, porter le même regard qu’à l’époque ? A-t-on le droit de juger de la vie d’autrui ? A-t-on le droit de dire qu’il aurait dû mourir ? Personnellement, je n’ai pas de réponse. Retenu par l’Histoire. Le film Titanic, de James Cameron, montre l’armateur voulant faire augmenter la vitesse du navire. Il désire que le voyage inaugural du Titanic fasse les gros titres de la presse. Le capitaine Smith est réticent, ne voulant pas pousser les moteurs tant qu’ils ne sont pas rodés. L’armateur, se déclarant simple passager, lui propose néanmoins une glorieuse fin de carrière en créant la surprise générale en arrivant le mardi soir1. Dans le film Titanic, d’Herbert Selpin et Werner Klinger, à mille lieues de la réalité, c’est par cupidité et esprit de lucre que l’armateur pousse le Joseph Bruce Ismay (1862-1937). capitaine Smith à battre le record de vitesse2. simple passager pour prendre place dans une La bande dessinée Titanic, de Richard Nolane et 6 Patrick Dumas, présente l’armateur comme un embarcation de sauvetage . homme sournois, proposant de décrocher le ruban Néanmoins, tout le monde ne le pointe pas d’un Bleu3. -

Titanic: Voices from the Disaster

******ebook converter DEMO Watermarks******* ******ebook converter DEMO Watermarks******* ******ebook converter DEMO Watermarks******* ******ebook converter DEMO Watermarks******* ******ebook converter DEMO Watermarks******* ******ebook converter DEMO Watermarks******* ******ebook converter DEMO Watermarks******* ******ebook converter DEMO Watermarks******* ******ebook converter DEMO Watermarks******* COVER FRONTISPIECE TITLE PAGE DEDICATION FOREWORD DIAGRAM OF THE SHIP CHAPTER ONE — Setting Sail CHAPTER TWO — A Floating Palace CHAPTER THREE — A Peaceful Sunday CHAPTER FOUR — “Iceberg Right Ahead.” CHAPTER FIVE — Impact! CHAPTER SIX — In the Radio Room: “It’s a CQD OM.” CHAPTER SEVEN — A Light in the Distance CHAPTER EIGHT — Women and Children First CHAPTER NINE — The Last Boats CHAPTER TEN — In the Water CHAPTER ELEVEN — “She’s Gone.” CHAPTER TWELVE — A Long, Cold Night CHAPTER THIRTEEN — Rescue at Dawn ******ebook converter DEMO Watermarks******* CHAPTER FOURTEEN — Aftermath: The End of All Hope EPILOGUE — Discovering the Titanic GLOSSARY PEOPLE IN THIS BOOK OTHER FAMOUS TITANIC FIGURES SURVIVOR LETTERS FROM THE CARPATHIA TITANIC TIMELINE BE A TITANIC RESEARCHER: FIND OUT MORE TITANIC FACTS AND FIGURES FROM THE BRITISH WRECK COMMISSIONER’S FINAL REPORT, 1912 TITANIC: THE LIFEBOAT LAUNCHING SEQUENCE REEXAMINED TITANIC Statistics: Who Lived and Who Died SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY SOURCE NOTES PHOTO CREDITS INDEX ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ABOUT THE AUTHOR ALSO BY THIS AUTHOR COPYRIGHT ******ebook converter DEMO Watermarks******* (Preceding image) The wreck of the Titanic. At 2:20 a.m. on Monday, April 15, 1912, the RMS Titanic, on her glorious maiden voyage from Southampton to New York, sank after striking an iceberg in the North Atlantic, killing 1,496 men, women, and children. A total of 712 survivors escaped with their lives on twenty lifeboats that had room for 1,178 people. -

Titanic Tribute 1912-2012 My Name Is Thomas Mccormack

Mrs. Moore Titanic Tribute 1912- 2012 My name is Margaret Fleming. At the Titanic Tribute st 1912-2012 age of 42, I was a 1 class passenger aboard the Titanic. I was traveling to Haverford, Pennsylvania with my employer, Mrs. Marian Thayer, her husband, Mr. John Thayer, and their son, Mr. John Thayer, Jr. We had spent a long time in Europe and were headed home to Haverford. I boarded Lifeboat 4. Titanic Tribute 1912-2012 My name is Thomas McCormack. When I was 19, I was a 3rd class passenger aboard the Titanic. I was traveling home to New Jersey after visiting my mum back in Ireland. I wasn’t allowed to board a lifeboat so I jumped and swam to one because many were launched half empty. I was traveling with a couple of cousins and was asleep when the accident happened. My name is Captain Edward John Smith. At Titanic Tribute the age of 62, I was the captain of the Titanic. 1912-2012 I was traveling from Southhampton, England without my family. The sailing of the Titanic was going to be my last trip before retiring. Sailing the Titanic and the passengers aside the ocean was suppose to be the greatest adventure of my life. I will always be known as the Captain of the Titanic that lost so many lives when it sank. I did not board a lifeboat and they never found my body. That’s my life as the Captain of the Titanic. Titanic Tribute My name is Annie Sage. I was born in 1867. -

CHRONOLOGY of EVENTS with REFERENCES and NOTES Revised: 07 July 2018

CHRONOLOGY OF EVENTS WITH REFERENCES AND NOTES Revised: 07 July 2018 This chronology reflects the order of events pertaining to the maiden voyage of Titanic. It is the most comprehensive and extensively referenced chronology of Titanic’s maiden voyage ever assembled, and first appeared in: Samuel Halpern, et al., Report Into the Loss of the SS Titanic – A Centennial Reappraisal, The History Press, 2011. It is primarily based upon evidence that comes from survivor accounts as given in sworn testimony, affidavits, letters, and other credible sources. The sources for the events included in this chronology are listed alongside each set grouped under a specified time. There is also a set of notes that explain how certain event times were derived, or offer additional pertinent information. In some cases, reference is made to specific articles and other publications where more details and in-depth explanations can be found. For most of the wireless messages shown, reliance was heavily placed on primary sources such as wireless logs or wireless station office forms that are available, rather than using some previously compiled list. In all cases, we have tried to insure the relative accuracy of event sequences. However, the accuracy of event times themselves cannot be guaranteed. The reader must understand that actual clock times were only known for a relatively few events where someone took the time off of a clock or a watch. Even for the times associated with wireless messages, where messages were recorded using a standard time reference such as New York time or Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), we find variances in the reported times put down by different operators describing the same communication. -

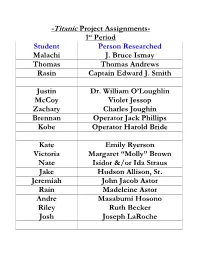

Titanic Project Assignments- 1St Period Student Person Researched Malachi J

-Titanic Project Assignments- 1st Period Student Person Researched Malachi J. Bruce Ismay Thomas Thomas Andrews Rasin Captain Edward J. Smith Justin Dr. William O’Loughlin McCoy Violet Jessop Zachary Charles Joughin Brennan Operator Jack Phillips Kobe Operator Harold Bride Kate Emily Ryerson Victoria Margaret “Molly” Brown Nate Isidor &/or Ida Straus Jake Hudson Allison, Sr. Jeremiah John Jacob Astor Rain Madeleine Astor Andre Masabumi Hosono Riley Ruth Becker Josh Joseph LaRoche Axel Frederick Goodwin Elliott Daniel Buckley Maddie Carla Jensen Kevin Olaus Abelseth Rocky 1st Officer William Murdoch Shani 2nd Officer Herbert Lightoller Dillon Quartermaster George Rowe Shawn Lookout Frederick Fleet Lisa Marian Thayer Michael John Thayer Annsley Charlotte Collyer Isabelly Bandmaster Wallace Hartley Gabby Selini “Celiney” Yazbeck Philip Zenni Kayli Alma Palsson Arabella Elsie Edith Bowerman Kayla Marie Young Helen Ostby Daisy Minahan Major Archibald Butt -Titanic Project Assignments- 2nd Period Student Person Researched Mauri J. Bruce Ismay Liam Thomas Andrews Charles Captain Edward J. Smith Basim Dr. William O’Loughlin Miriam Violet Jessop Asher Charles Joughin Carlos Operator Jack Phillips Shep Operator Harold Bride Karma Emily Ryerson Rhea Margaret “Molly” Brown Dazzetta Isidor &/or Ida Straus Taylor Hudson Allison, Sr. Sam John Jacob Astor Milele Madeleine Astor Drew Masabumi Hosono Yozmarie Ruth Becker Patrick Joseph LaRoche Brenden Frederick Goodwin Noah Daniel Buckley Aerial Carla Jensen Garrett Olaus Abelseth Andreas 1st Officer William Murdoch Matt 2nd Officer Herbert Lightoller Maddy Quartermaster George Rowe Abby Lookout Frederick Fleet Angelina Marian Thayer Duffy John Thayer Allyria Charlotte Collyer Hailey Bandmaster Wallace Hartley Yasmin Selini “Celiney” Yazbeck Naomi Philip Zenni Rebecca Alma Palsson Meadow Elsie Edith Bowerman Marie Young Helen Ostby Daisy Minahan Major Archibald Butt -Titanic Project Assignments- 5th Period Student Person Researched Erik J. -

Thayer Family Collection 1989.033 Finding Aid Prepared by Megan Hahn Fraser

Thayer family collection 1989.033 Finding aid prepared by Megan Hahn Fraser. Last updated on August 02, 2012. Independence Seaport Museum, J. Welles Henderson Archives and Library 2010.11.29 Thayer family collection Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................6 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 7 - Page 2 - Thayer family collection Summary Information Repository Independence Seaport Museum, J. Welles Henderson Archives and Library Creator Thayer Title Thayer family collection Call number 1989.033 Date [inclusive] 1892-1986 Extent 10 boxes Language English Abstract The Thayers were a prominent Philadelphia-area family at the turn of the 20th century. John Borland Thayer, Jr. was a vice-president -

John B. Thayer Memorial Collection of the Sinking of the Titanic Ms

John B. Thayer memorial collection of the sinking of the Titanic Ms. Coll. 968 Finding aid prepared by Holly Mengel. Last updated on April 24, 2020. University of Pennsylvania, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts 2014 April 7 John B. Thayer memorial collection of the sinking of the Titanic Table of Contents Summary Information...................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History.........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents.......................................................................................................................................4 Administrative Information...........................................................................................................................5 Related Materials ......................................................................................................................................... 6 Controlled Access Headings......................................................................................................................... 6 Collection Inventory..................................................................................................................................... 8 Series I. First-hand accounts of the sinking of the Titanic......................................................................8 Series II. Thayer -

Titanic Websites

P R O D U C T I O N N O T E S CONTENTS Pages Production Interviews: Julian Fellowes – Writer ..................................................................................................4 - 7 Nigel Stafford-Clark – Producer ...................................................................................8 - 12 Jon Jones – Director ....................................................................................................13 - 15 Simon Vaughan - Executive Producer (Lookout Point)!.......................................16 - 17 Chris Thompson – Producer .....................................................................................18 - 19 Rob Harris - Production Designer ..............................................................................20 - 21 James Keast - Costume Designer .............................................................................22 - 24 Csilla Horváth - Make Up ...........................................................................................25 - 26 Cast Interviews: Linus Roache plays Hugh, Earl of Manton ...............................................................27 - 29 Geraldine Somerville plays Louisa, Countess of Manton .......................................30 - 32 Perdita Weeks plays Lady Georgiana Grex, the Mantons’ daughter ....................33 - 35 Noah Reid plays Harry Widener .................................................................................36 - 37 Steven Waddington plays Second Officer Lightoller ................................................38 -

Does Anyone Really Know What Time It Was?

1 DOES ANYONE REALLY KNOW WHAT TIME IT WAS? A Treatise About Time (Revised and Expanded 07 April 2019) By Samuel Halpern On the night of April 14, 1912, at 10:25pm in New York (NY), a spark-excited radio transmitter blasted out a stream of radio waves into the night air. To wireless operators stationed on the steamships La Provence, Mount Temple, and Frankfurt, and to the wireless operator stationed at Cape Race, Nova Scotia, there came the staccato sounds of a series of dots and dashes that read: CQD DE MGY Require assistance. Position 41.44 north, longitude 50.24 west. Come at once. Iceberg. It was a general call of distress (CQD) to anyone who could hear from the steamship Titanic (radio call letters MGY) on her maiden voyage to New York. Ten minutes later, at 10:35pm New York time, Titanic sends: MGY CQD Here corrected position 41.46 north, longitude 50.14 west. Require immediate assistance. We have collision with iceberg. Sinking. Can hear nothing for noise of steam. For 73 years, the wreck of Titanic remained a mystery, lying at the bottom of the Atlantic ocean some 13 nautical miles to the east of the so called “corrected” distress position of 41° 46’N, 50° 14’W. Yet, back in 1912, all of Titanic’s surviving officers, as well as Captain Rostron of the rescue ship Carpathia, believed Titanic had gone down in the position worked out by Titanic’s fourth officer Joseph Boxhall. In 1985 Dr. Robert Ballard proved that they were wrong.