` Overview of the Comparison of Commercial Pelagic Species

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A COMPARATIVE ACCOUNT of the SMALL PELAGIC FISHERIES in the APFIC REGION by M

A COMPARATIVE ACCOUNT OF THE SMALL PELAGIC FISHERIES IN THE APFIC REGION by M. Devaraj and E. Vivekanandan Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute Cocbin-682014, India Abstract The production of the small pe/agics in the APFIC region was 1.2 mt/sq. km during 1995. Among the four areas in the region, the small pe/agics have registered (i) the maximum annual fluctuations in the western Indian Ocean; (ii) the highest increase duri'}i the past two decades along the west coast of Thailand in the eastern Indian Ocean; and (iii) the consistent decline in the landings during the past one decade along the Japanese coast in the northwest Pacific Ocean. The short rnackerels emerged as the largest fishery in the APFlC region, fom'ing 19.5% of the landings of the small pelagics in 1995. The group consisting afthe sardines and the anchovies has shown clear signs of decline during the past one decade in almost the entire region. Most of the small pelagics have unique biological characteristics such as fast growth, short longevity, late maturity, high nalllral mortality, shoaling behaviour, high fecundity and severe recruitment fluctuations. As many species of the small pelagics undertake migration, collaborative research programmes and close coordination are required among the APFle countries for the stock assessment of all the major species. The management measures under implementation in these countries have been reviewed, with suggestions for regional cooperation for the management of the stocks of the small pelagics. INTRODUCTION The Asia-Pacific Fishery Commission covers four oceanic areas, which have been classified by the FAO as the western Indian Ocean (FAO Statistical Area 51), eastern Indian Ocean (Area 57) , northwest Pacific Ocean (Area 61) and western central Pacific Ocean (Area 71). -

Grade 3 Unit 2 Overview Open Ocean Habitats Introduction

G3 U2 OVR GRADE 3 UNIT 2 OVERVIEW Open Ocean Habitats Introduction The open ocean has always played a vital role in the culture, subsistence, and economic well-being of Hawai‘i’s inhabitants. The Hawaiian Islands lie in the Pacifi c Ocean, a body of water covering more than one-third of the Earth’s surface. In the following four lessons, students learn about open ocean habitats, from the ocean’s lighter surface to the darker bottom fl oor thousands of feet below the surface. Although organisms are scarce in the deep sea, there is a large diversity of organisms in addition to bottom fi sh such as polycheate worms, crustaceans, and bivalve mollusks. They come to realize that few things in the open ocean have adapted to cope with the increased pressure from the weight of the water column at that depth, in complete darkness and frigid temperatures. Students fi nd out, through instruction, presentations, and website research, that the vast open ocean is divided into zones. The pelagic zone consists of the open ocean habitat that begins at the edge of the continental shelf and extends from the surface to the ocean bottom. This zone is further sub-divided into the photic (sunlight) and disphotic (twilight) zones where most ocean organisms live. Below these two sub-zones is the aphotic (darkness) zone. In this unit, students learn about each of the ocean zones, and identify and note animals living in each zone. They also research and keep records of the evolutionary physical features and functions that animals they study have acquired to survive in harsh open ocean habitats. -

Tennessee Fish Species

The Angler’s Guide To TennesseeIncluding Aquatic Nuisance SpeciesFish Published by the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency Cover photograph Paul Shaw Graphics Designer Raleigh Holtam Thanks to the TWRA Fisheries Staff for their review and contributions to this publication. Special thanks to those that provided pictures for use in this publication. Partial funding of this publication was provided by a grant from the United States Fish & Wildlife Service through the Aquatic Nuisance Species Task Force. Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency Authorization No. 328898, 58,500 copies, January, 2012. This public document was promulgated at a cost of $.42 per copy. Equal opportunity to participate in and benefit from programs of the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency is available to all persons without regard to their race, color, national origin, sex, age, dis- ability, or military service. TWRA is also an equal opportunity/equal access employer. Questions should be directed to TWRA, Human Resources Office, P.O. Box 40747, Nashville, TN 37204, (615) 781-6594 (TDD 781-6691), or to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Office for Human Resources, 4401 N. Fairfax Dr., Arlington, VA 22203. Contents Introduction ...............................................................................1 About Fish ..................................................................................2 Black Bass ...................................................................................3 Crappie ........................................................................................7 -

Atlantic "Pelagic" Fish Underwater World

QL DFO - Library / MPO - Bibliothèque 626 U5313 no.3 12064521 c.2 - 1 Atlantic "Pelagic" Fish Underwater World Fish that range the open sea are Pelagic species are generally very Atlantic known as " pelagic" species, to dif streamlined. They are blue or blue ferentiate them from "groundfish" gray over their backs and silvery "Pelagic" Fish which feed and dwell near the bot white underneath - a form of tom . Feeding mainly in surface or camouflage when in the open sea. middle depth waters, pelagic fish They are caught bath in inshore travel mostly in large schools, tu. n and offshore waters, principally with ing and manoeuvring in close forma mid-water trawls, purse seines, gill tion with split-second timing in their nets, traps and weirs. quest for plankton and other small species. Best known of the pelagic popula tions of Canada's Atlantic coast are herring, but others in order of economic importance include sal mon, mackerel , swordfish, bluefin tuna, eels, smelt, gaspereau and capelin. Sorne pelagic fish, notably salmon and gaspereau, migrate from freshwater to the sea and back again for spawning. Eels migrate in the opposite direction, spawning in sait water but entering freshwater to feed . Underwater World Herring comprise more than one Herring are processed and mar Atlantic Herring keted in various forms. About half of (Ctupea harengus) fifth of Atlantic Canada's annual fisheries catch. They are found all the catch is marketed fresh or as along the northwest Atlantic coast frozen whole dressed fish and fillets, from Cape Hatteras to Hudson one-quarter is cured , including Strait. -

Forage Fish Management Plan

Oregon Forage Fish Management Plan November 19, 2016 Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Marine Resources Program 2040 SE Marine Science Drive Newport, OR 97365 (541) 867-4741 http://www.dfw.state.or.us/MRP/ Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Purpose and Need ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Federal action to protect Forage Fish (2016)............................................................................................ 7 The Oregon Marine Fisheries Management Plan Framework .................................................................. 7 Relationship to Other State Policies ......................................................................................................... 7 Public Process Developing this Plan .......................................................................................................... 8 How this Document is Organized .............................................................................................................. 8 A. Resource Analysis .................................................................................................................................... -

Lake Tahoe Fish Species

Description: o The Lohonton cutfhroot trout (LCT) is o member of the Solmonidqe {trout ond solmon) fomily, ond is thought to be omong the most endongered western solmonids. o The Lohonton cufihroot wos listed os endongered in 1970 ond reclossified os threotened in 1975. Dork olive bdcks ond reddish to yellow sides frequently chorocterize the LCT found in streoms. Steom dwellers reoch l0 inches in length ond only weigh obout I lb. Their life spon is less thon 5 yeors. ln streoms they ore opportunistic feeders, with diets consisting of drift orgonisms, typicolly terrestriol ond oquotic insects. The sides of loke-dwelling LCT ore often silvery. A brood, pinkish stripe moy be present. Historicolly loke dwellers reoched up to 50 inches in length ond weigh up to 40 pounds. Their life spon is 5-14yeors. ln lokes, smoll Lohontons feed on insects ond zooplonkton while lorger Lohonions feed on other fish. Body spots ore the diognostic chorocter thot distinguishes the Lohonion subspecies from the .l00 Poiute cutthroot. LCT typicolly hove 50 to or more lorge, roundish-block spots thot cover their entire bodies ond their bodies ore typicolly elongoted. o Like other cufihroot trout, they hove bosibronchiol teeth (on the bose of tongue), ond red sloshes under their iow (hence the nome "cutthroot"). o Femole sexuol moturity is reoch between oges of 3 ond 4, while moles moture ot 2 or 3 yeors of oge. o Generolly, they occur in cool flowing woier with ovoiloble cover of well-vegetoted ond stoble streom bonks, in oreos where there ore streom velocity breoks, ond in relotively silt free, rocky riffle-run oreos. -

Why Study Bycatch? an Introduction to the Theme Section on Fisheries Bycatch

Vol. 5: 91–102, 2008 ENDANGERED SPECIES RESEARCH Printed December 2008 doi: 10.3354/esr00175 Endang Species Res Published online December xx, 2008 Contribution to the Theme Section ‘Fisheries bycatch problems and solutions’ OPENPEN ACCESSCCESS Why study bycatch? An introduction to the Theme Section on fisheries bycatch Candan U. Soykan1,*, Jeffrey E. Moore2, Ramunas ¯ 5ydelis2, Larry B. Crowder2, Carl Safina3, Rebecca L. Lewison1 1Biology Department, San Diego State University, 5500 Campanile Dr., San Diego, California 92182-4614, USA 2Center for Marine Conservation, Nicholas School of the Environment, Duke University Marine Laboratory, 135 Duke Marine Lab Road, Beaufort,North Carolina 28516, USA 3Blue Ocean Institute, PO Box 250, East Norwich, New York 11732, USA ABSTRACT: Several high-profile examples of fisheries bycatch involving marine megafauna (e.g. dolphins in tuna purse-seines, albatrosses in pelagic longlines, sea turtles in shrimp trawls) have drawn attention to the unintentional capture of non-target species during fishing operations, and have resulted in a dramatic increase in bycatch research over the past 2 decades. Although a number of successful mitigation measures have been developed, the scope of the bycatch problem far exceeds our current capacity to deal with it. Specifically, we lack a comprehensive understanding of bycatch rates across species, fisheries, and ocean basins, and, with few exceptions, we lack data on demographic responses to bycatch or the in situ effectiveness of existing mitigation measures. As an introduction to this theme section of Endangered Species Research ‘Fisheries bycatch: problems and solutions’, we focus on 5 bycatch-related questions that require research attention, building on exam- ples from the current literature and the contributions to this Theme Section. -

Ecosystem-Based Fisheries Management Improving the Resilience of Ocean Ecosystems to Support Fish Populations, Coastal Communities

A brief from March 2014 Ecosystem-Based Fisheries Management Improving the resilience of ocean ecosystems to support fish populations, coastal communities The fish on the end of your line, the little forage fish that feed the big fish, the corals that build reef habitats, and the catch of the day in your favorite restaurant are interconnected parts of a vibrant ocean ecosystem. Ensuring the long-term health of important marine species will depend upon our ability to understand and account for the interactions among those species, their environment, and the people who rely upon them for food, commerce, and sport. This comprehensive approach, called ecosystem-based fisheries management, is needed to conserve the healthy ecosystems essential to the sustainability of our fisheries and to deal with the increasingly complex challenges facing our oceans. The United States is a global leader in fisheries management and has made great strides in ending overfishing (the problem of catching fish faster than they can reproduce) and rebuilding vulnerable populations under the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act—the primary law governing U.S. ocean fisheries. In many regions of our nation, this progress has helped reestablish more abundant fish populations and created economic benefits for the fishing industry and coastal communities. Core conservation policies added to the law in 1996 and 2007 are fundamental to improving individual fish populations and returning value to fishermen. We must maintain them as the foundation for sustainable management. But the United States should make the transition from a species-by-species approach to ecosystem-based fisheries management to meet the rising and urgent challenges of damaged ocean environments and dynamic, changing oceans. -

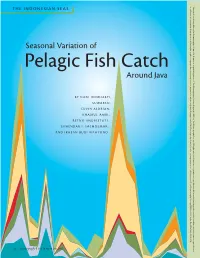

Pelagic Fish Catch Or Other Means Reposting, Photocopy Machine, Is Only W Permitted Around Java E Oceanography Society

or collective redistirbution of any portion article of any by of this or collective redistirbution Th THE INDONESIAN SEAS articleis has been in published Oceanography Seasonal Variation of 18, Number journal of Th 4, a quarterly , Volume Pelagic Fish Catch permitted only w is photocopy machine, reposting, means or other Around Java 2005 by Th e Oceanography Copyright Society. BY NANI HENDIARTI, SUWARSO, EDVIN ALDRIAN, of Th approval the ith KHAIRUL AMRI, RETNO ANDIASTUTI, gran e Oceanography is Society. All rights reserved. Permission SUHENDAR I. SACHOEMAR, or Th e Oceanography [email protected] Society. Send to: all correspondence AND IKHSAN BUDI WAHYONO ted to copy this article Repu for use copy this and research. to in teaching ted e Oceanography Society, PO Box 1931, Rockville, MD 20849-1931, USA. blication, systemmatic reproduction, reproduction, systemmatic blication, 112 Oceanography Vol. 18, No. 4, Dec. 2005 WE PRESENT DATA on the seasonal variability of small and 1.26 million ton/year in the Indonesian EEZ. Pelagic fi sh pelagic fi sh catches and their relation to the coastal processes play an important role in the economics of fi sherman in Indo- responsible for them around the island of Java. This study uses nesia; approximately 75 percent of the total fi sh stock, or 4.8 long fi sh-catch records (up to twenty years) collected at vari- million ton/year, is pelagic fi sh. In particular, we investigated ous points around Java that were selected from the best-qual- the waters around Java because most people live near the coast ity harbor records. -

Coastal Upwelling Revisited: Ekman, Bakun, and Improved 10.1029/2018JC014187 Upwelling Indices for the U.S

Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans RESEARCH ARTICLE Coastal Upwelling Revisited: Ekman, Bakun, and Improved 10.1029/2018JC014187 Upwelling Indices for the U.S. West Coast Key Points: Michael G. Jacox1,2 , Christopher A. Edwards3 , Elliott L. Hazen1 , and Steven J. Bograd1 • New upwelling indices are presented – for the U.S. West Coast (31 47°N) to 1NOAA Southwest Fisheries Science Center, Monterey, CA, USA, 2NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory, Boulder, CO, address shortcomings in historical 3 indices USA, University of California, Santa Cruz, CA, USA • The Coastal Upwelling Transport Index (CUTI) estimates vertical volume transport (i.e., Abstract Coastal upwelling is responsible for thriving marine ecosystems and fisheries that are upwelling/downwelling) disproportionately productive relative to their surface area, particularly in the world’s major eastern • The Biologically Effective Upwelling ’ Transport Index (BEUTI) estimates boundary upwelling systems. Along oceanic eastern boundaries, equatorward wind stress and the Earth s vertical nitrate flux rotation combine to drive a near-surface layer of water offshore, a process called Ekman transport. Similarly, positive wind stress curl drives divergence in the surface Ekman layer and consequently upwelling from Supporting Information: below, a process known as Ekman suction. In both cases, displaced water is replaced by upwelling of relatively • Supporting Information S1 nutrient-rich water from below, which stimulates the growth of microscopic phytoplankton that form the base of the marine food web. Ekman theory is foundational and underlies the calculation of upwelling indices Correspondence to: such as the “Bakun Index” that are ubiquitous in eastern boundary upwelling system studies. While generally M. G. Jacox, fi [email protected] valuable rst-order descriptions, these indices and their underlying theory provide an incomplete picture of coastal upwelling. -

Other Processes Regulating Ecosystem Productivity and Fish Production in the Western Indian Ocean Andrew Bakun, Claude Ray, and Salvador Lluch-Cota

CoaStalUpwellinO' and Other Processes Regulating Ecosystem Productivity and Fish Production in the Western Indian Ocean Andrew Bakun, Claude Ray, and Salvador Lluch-Cota Abstract /1 Theseasonal intensity of wind-induced coastal upwelling in the western Indian Ocean is investigated. The upwelling off Northeast Somalia stands out as the dominant upwelling feature in the region, producing by far the strongest seasonal upwelling pulse that exists as a; regular feature in any ocean on our planet. It is surmised that the productive pelagic fish habitat off Southwest India may owe its particularly favorable attributes to coastal trapped wave propagation originating in a region of very strong wind-driven offshore trans port near the southern extremity of the Indian Subcontinent. Effects of relatively mild austral summer upwelling that occurs in certain coastal ecosystems of the southern hemi sphere may be suppressed by the effects of intense onshore transport impacting these areas during the opposite (SW Monsoon) period. An explanation for the extreme paucity of fish landings, as well as for the unusually high production of oceanic (tuna) fisheries relative to coastal fisheries, is sought in the extremely dissipative nature of the physical systems of the region. In this respect, it appears that the Gulf of Aden and some areas within the Mozambique Channel could act as important retention areas and sources of i "see6stock" for maintenance of the function and dillersitv of the lamer reoional biolooical , !I ecosystems. 103 104 large Marine EcosySlIlms ofthe Indian Ocean - . Introduction The western Indian Ocean is the site ofsome of the most dynamically varying-. large marine ecosystems (LMEs) that exist on our planet. -

The Turtle and the Hare: Reef Fish Vs. Pelagic

Part 5 in a series about inshore fi sh of Hawaii. The 12-part series is a project of the Hawaii Fisheries Local Action Strategy. THE TURTLE AND THE HARE: Surgeonfi sh REEF FISH VS. PELAGIC BY SCOTT RADWAY Tuna Photo: Scott Radway Photo: Reef fi sh and pelagic fi sh live in the same ocean, but lead very different lives. Here’s a breakdown of the differences between the life cycles of the two groups. PELAGIC Pelagic Fish TOPIC Photo: Gilbert van Ryckevorsel Photo: VS. REEF • Can grow up to 30 pounds in fi rst two years • Early sexual maturity WHEN TUNA COME UPON A BIG SCHOOL OF PREY FISH, IT’S FRENETIC. “Tuna can eat up to a quarter • Periodically abundant recruitment of their body weight in one day,” says University of Hawaii professor Charles Birkeland. Feeding activity is some- • Short life times so intense a tuna’s body temperature rises above the water temperature, causing “burns” in the muscle • Live in schools tissue and lowering the market value of the fi sh. • Travel long distances Other oceanic, or pelagic, fi sh, like the skipjack and the mahimahi, feed the same way, searching the ocean for (Hawaii to Philippines) pockets of food fi sh and gorging themselves. • Rapid population turnover On a coral reef, fi sh life is very different. On a reef, it might appear that there are plenty of fi sh for eating, but it is far from the all-you-can-eat buffet Reef Fish pelagic fi sh can fi nd in schooling prey fi sh.