Understanding 'Local' Opposition to Wind Development in the UK: How Big Is a Backyard?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sustainable Communities and Wind Energy Project Acceptance in Massachusetts

Sustainable Communities and Wind Energy Project Acceptance in Massachusetts Maria A. Petrova, PhD* I. Background ..................................................................... 530 II. Study Context ................................................................. 534 III. Literature Review and Research Questions .................. 539 IV. Methods ........................................................................... 543 V. Results............................................................................. 544 VI. Discussion and Conclusion ............................................. 551 The State of Massachusetts is one of the most progressive U.S. states in advancing sustainability through energy conservation and renewable energy. The Green Communities Act,1 signed into law by Governor Deval Patrick in 2008, has awarded 110 communities with the title “Green Communities” in the last five years.2 The title is earned after communities achieve “five clean energy benchmarks,”3 two of which are the provision of “as-of-right” siting for renewable/alternative energy generation and the adoption of an expedited application © 2014 Maria A. Petrova, PhD * Center for International Environment and Resource Policy, The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University, 160 Packard Ave, Medford, MA 02155, [email protected]. This work was done as a Postdoctoral Scholar at the Energy, Climate, and Innovation (ECI) Program in the Center for International Environment and Resource Policy (CIERP) at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University. Financial support was provided through a grant to ECI from BP Group and Barbara Kates- Garnick. I am grateful for the review assistance of Professor Kelly Sims Gallagher and the research help of students Allison Thompson, Elena Nikolova, and Chantal Davis. 1. An Act Relative to Green Communities, 2008 Mass. Acts 308–80. 2. Press Release, Mass. Exec. Office of Energy & Envtl. Affairs, Patrick- Murray Administration Energy Officials Present Green Communities Award (Apr. -

The Development and Improvement of Instructions

COMMUNITY BENEFIT FUNDS AND WIND POWER: A SCOTTISH CASE STUDY Dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE WITH A MAJOR IN WIND POWER PROJECT MANAGEMENT Uppsala University Department of Earth Sciences, Campus Gotland Adam Christopher Mathers COMMUNITY BENEFIT FUNDS AND WIND POWER: A SCOTTISH CASE STUDY Dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE WITH A MAJOR IN WIND POWER PROJECT MANAGEMENT Uppsala University Department of Earth Sciences, Campus Gotland Approved by: Supervisor, Dr Sanna Mels Examiner, Dr Heracles Polatidis Oct 2018 iii ABSTRACT The Scottish government’s aim of deriving 100 per cent of the nation’s electricity from renewable sources is dependent on the utilisation of wind energy. Social barriers, however, have continued to threaten these targets. Community benefit funds have often been paraded as the most common way of improving public attitudes towards wind farms in the United Kingdom, although little empirical evidence exists to support this notion. Using the proposed Ourack wind farm, approximately three and a half miles north of Grantown-on-Spey in the Scottish Highlands, this case study, consisting of a sequential explanatory research design comprised of an initial close-ended survey followed by in-depth semi-structured interviews, sought to explore the community’s perceptions of community benefits, identify the type of fund that the community wanted, and investigate the role of such benefit provisions in altering perceptions of wind farms. The key findings indicated that the majority of participants were in favour of benefits being provided, they preferred funding to be directed towards community organisations, and approximately one third of research participants (31.6 per cent) perceived the proposed wind farm in a more positive light after considering the possible benefits the region would accrue. -

Scottish Government Good Practice Principles for Community Benefits from Onshore Renewable Energy Developments Cares Supports Local Renewable Energy Generation

ScottIsh Government Good practIce prIncIples for CommunIty benefIts from Onshore renewable Energy developments CarEs supports Local renewable energy generatIon Contents 1 Foreword ................................................................ 3 2 Introduction and overview ....................................... 4 3 Basic principles of community benefits ...................... 6 4 Community investment ............................................ 8 5 Other forms of community benefit ........................... 10 6 Identification of the community ............................... 12 7 Public consultation on community benefit schemes ... 16 8 Supporting effective fund spend .............................. 20 9 Fund administration and governance....................... 24 10 Ongoing role of developer .................................... 26 11 ANNEXES ............................................................ 28 This document is available alongside the shared ownership annex at: www.localenergyscotland.org/goodpractice Revised September 2015 for accuracy. 2 1 foreword winter 2013/14 and we are grateful for the work Renewable energy in Scotland presents an uprecedented opportunity for communities of the informal stakeholder group, as listed in to share in the benefits of their local energy Annex 11.5, convened under our Community and resources. Renewable Energy Scheme (CARES). We think this has produced a very helpful national reference to The Scottish Government has no powers to guide what is a voluntary local process, and we oblige developers -

(For Official Use Only) PUBLIC PETITION NO. PE1188 Should You Wish to Submit a Public Petition for Consideration by the Public P

(For official use only) PUBLIC PETITION NO. PE1188 Should you wish to submit a public petition for consideration by the Public Petitions Committee please refer to the guidance leaflet How to submit a public petition and the Guidance Notes at the back of this form. 1. NAME OF PRINCIPAL PETITIONER Nick Dekker 2. TEXT OF PETITION Nick Dekker calling on the Scottish Parliament to urge the Scottish Government to investigate the circumstances whereby it agreed that 60 hydro-power stations could be accredited for subsidy under the Renewables Obligation scheme and that generation capacity could be cut to below the 20megawatt qualification threshold at others to enable accreditation and whether, in the interests of electricity consumers, it will rescind these accreditations. 3. ACTION TAKEN TO RESOLVE ISSUES OF CONCERN BEFORE SUBMITTING THE PETITION I have contacted and have been in correspondence with AuditScotland, OFGEM, Scottish & Southern Energy PLC and ScottishPower PLC. Alex Neil MSP also corresponded with Scottish & Southern Energy. 4. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION See— “The war on climate change – A licence to print money?” “Subsidies and Subterfuge – Hydro-power and the Renewables Obligation” (also on www.swap.org.uk) “ROCs earned by Alcan, SSE and ScottishPower from 'old build' hydro, April 2002 to December 2007” (a report by the petitioners); “Renewable Energy Data for Scotland (Hydro), May 2008” Correspondence generally pertinent to the petition but esp to Question 3 OFGEM’s “Annual Reports on the Renewables Obligation” 2004 to 2008; Press releases and other material referred to in “The war on climate change – a licence to print money?” and elsewhere 5. -

Memorandum Submitted by the Department of Energy and Climate Change (WIND 01)

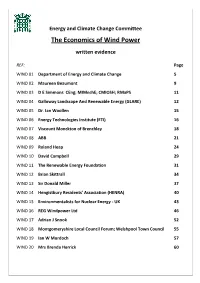

Energy and Climate Change Committee The Economics of Wind Power written evidence REF: Page WIND 01 Department of Energy and Climate Change 5 WIND 02 Maureen Beaumont 9 WIND 03 D E Simmons CEng; MIMechE; CMIOSH; RMaPS 11 WIND 04 Galloway Landscape And Renewable Energy (GLARE) 12 WIND 05 Dr. Ian Woollen 15 WIND 06 Energy Technologies Institute (ETI) 16 WIND 07 Viscount Monckton of Brenchley 18 WIND 08 ABB 21 WIND 09 Roland Heap 24 WIND 10 David Campbell 29 WIND 11 The Renewable Energy Foundation 31 WIND 12 Brian Skittrall 34 WIND 13 Sir Donald Miller 37 WIND 14 Hengistbury Residents' Association (HENRA) 40 WIND 15 Environmentalists for Nuclear Energy ‐ UK 43 WIND 16 REG Windpower Ltd 46 WIND 17 Adrian J Snook 52 WIND 18 Montgomeryshire Local Council Forum; Welshpool Town Council 55 WIND 19 Ian W Murdoch 57 WIND 20 Mrs Brenda Herrick 60 WIND 21 Mr N W Woolmington 62 WIND 22 Professor Jack W Ponton FREng 63 WIND 23 Mrs Anne Rogers 65 WIND 24 Global Warming Policy Foundation (GWPF) 67 WIND 25 Derek Partington 70 WIND 26 Professor Michael Jefferson 76 WIND 27 Robert Beith CEng FIMechE, FIMarE, FEI and Michael Knowles CEng 78 WIND 28 Barry Smith FCCA 81 WIND 29 The Wildlife Trusts (TWT) 83 WIND 30 Wyck Gerson Lohman 87 WIND 31 Brett Kibble 90 WIND 32 W P Rees BSc. CEng MIET 92 WIND 33 Chartered Institution of Water and Environmental Management 95 WIND 34 Councillor Ann Cowan 98 WIND 35 Ian M Thompson 99 WIND 36 E.ON UK plc 102 WIND 37 Brian D Crosby 105 WIND 38 Peter Ashcroft 106 WIND 39 Campaign to Protect Rural England (CPRE) 109 WIND 40 Scottish Renewables 110 WIND 41 Greenpeace UK; World Wildlife Fund; Friends of the Earth 114 WIND 42 Wales and Borders Alliance 119 WIND 43 National Opposition to Windfarms 121 WIND 44 David Milborrow 124 WIND 45 SSE 126 WIND 46 Dr Howard Ferguson 129 WIND 47 Grantham Research Institute 132 WIND 48 George F Wood 135 WIND 49 Greenersky. -

Community Benefits from Offshore Renewable Energy Developments

ScottIsh Government Good practIce prIncIples for CommunIty benefIts from Offshore renewable Energy developments 1 1 IntroductIon Scotland is estimated to have around a quarter of Europe’s potential offshore wind resources, and The Scottish Contents Government wishes to see communities across the country share in the benefits 1. Introduction 2. Principles from this rich natural resource. 3. Background 4. Designing a Community Benefit Package for Offshore Renewable Energy Projects The Scottish Government’s National Marine Plan While the majority of this document is intended to 5. Identification of Community (NMP) Renewables Policy 10 states that “Good be for developers of wind projects, it is proposed 6. Maximising Impact of Benefit Practice guidance for community benefit from that this document will be reviewed over the 7. Further Principles offshore wind and marine renewable energy coming years to incorporate guidance and good development should be followed by developers, practice for other offshore technologies. 8. Case Studies where appropriate”. This document looks at good 9. Further Reading practice in shaping and delivering community This document is split into definitions, context, 10. Glossary benefits from offshore renewable energy projects, good practice expectations and supplementary complementary to environmental, supply chain guidance for all involved. The intended readers of and other socio-economic benefits to Scotland. this document are developers, communities, local authorities and other stakeholders. When providing community benefits from offshore renewables, there are a number of factors to be The Scottish Government is committed to This document is available at: considered such as identifying the community, supporting the development of a successful www.localenergyscotland.org/goodpractice. -

Experiences of Place and Change in Rural Landscapes: Three English Case Studies

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk 04 University of Plymouth Research Theses 01 Research Theses Main Collection 2015 Experiences of Place and Change in Rural Landscapes: Three English Case Studies Wheeler, Rebecca http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/3366 Plymouth University All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. EXPERIENCES OF PLACE AND CHANGE IN RURAL LANDSCAPES: THREE ENGLISH CASE STUDIES by REBECCA WHEELER A thesis submitted to Plymouth University in partial fulfilment for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences December 2014 Copyright Statement This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author's prior consent. i Abstract This thesis examines how changes to rural places and landscapes are experienced by residents and incorporated into place attachments and identities over time. It does so through exploring findings from seventy-eight qualitative, ‘emplaced’, oral history interviews in three English villages: Mullion (Cornwall); Askam and Ireleth (Cumbria); and Martham (Norfolk). These villages are located near to at least one existing windfarm, which – as an example of rural change - provides a common focus for the research. -

Onshore Wind Policy Statement

ONSHORE WIND POLICY STATEMENT January 2017 1. Introduction – the case for onshore wind 1 1. INTRODUCTION - THE CASE FOR ONSHORE WIND We are publishing this draft statement, alongside the draft Energy Strategy. Onshore wind development is essential to Scotland’s transformation to a fully decarbonised energy system by 2050 and brings opportunities which underpin our vision to grow a low carbon economy and build a fairer society. This statement reaffirms the Scottish Government’s existing onshore wind policy set out in previous publications and seeks views on a number of issues related to supporting the sector. It includes separate sections on key priority areas: • Route to market • Repowering • Developing a Strategic Approach to New Development • Barriers to deployment • Protection for residents and the environment • Community benefits • Shared ownership Our current policy is to support deployment of onshore wind, whilst protecting the environment (landscape and visual, ecological and other environmental impacts); protecting residential amenity; and maximising local benefits, including through promoting shared ownership and community benefits.1 Economic Benefits of Onshore wind in Scotland The Office of National Statistics (ONS) figures on the low carbon and renewable energy economy in the UK for 20141 show that: • for onshore wind, Scotland has 46% of all UK employment and 57% of all UK turnover; and • onshore wind activity (direct and indirect) accounted for £3.2 billion in turnover, 30% of total Scottish low carbon and renewable turnover. Onshore wind also accounted for 14% of total low carbon and renewable employment in Scotland. Although electricity generation energy policy is largely reserved to the UK Government, the Scottish Government wishes to make full use of its devolved powers to promote investment in appropriately sited onshore wind. -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Assessing energy security in a low-carbon context The case of electricity in the UK Emily M. Cox DPhil Thesis University of Sussex May 2016 3 Acknowledgments Undertaking this PhD has given me some of the most enjoyable years of my life, all thanks to the following people; there’s no way I would have come this far without you. First of all, I would like to thank my supervisors Jim Watson, Florian Kern and Matt Copeland. I’m not exaggerating when I say that I honestly couldn’t have wished for a better set of supervisors: you’ve given me support, encouragement and constructive criticism in exactly the right measures and at all the right times. I dearly hope that your hard work on this thesis pays off; it’s your thesis as much as mine. Further thanks go to Andy Boston for continuing to advise me despite moving to a new job. Also thanks to little Adam Kern, for arriving right on time and making Florian visibly very happy! I would also like to thank the funders of this project for their generous support. -

EIAR Bibliography

Derrinlough Wind Farm Environmental Impact Assessment Report EIAR – 2020.02.14 – 171221 - F BIBLIOGRAPHY Introduction Department of the Environment, Community and Local Government (2013). Guidelines for Planning Authorities and An Bord Pleanála on carrying out Environmental Impact Assessment. DoEHLG, Dublin. Department of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government (2006). Wind Energy Development Guidelines for Planning Authorities. DoEHLG, Dublin. Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government (December 2019) Draft Revised Wind Energy Development Guidelines. DHPLG, Dublin. Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government (August 2018) Guidelines for Planning Authorities and An Bord Pleanála on Carrying out Environmental Impact Assessment. DHPLG, Dublin. Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government (June 2017) Review of the Wind Energy Development Guidelines 2006 – Preferred Draft Approach. DHPLG, Dublin. Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government (2013) Proposed Revisions to Wind Energy Development Guidelines 2006 – Targeted Review. DHPLG, Dublin. Environmental Protection Agency (August 2017): Draft Guidelines on the Information to be Contained in Environmental Impact Assessment Reports. EPA, Wexford. Environmental Protection Agency (September 2015): Draft - Advice Notes on Current Practice (in the preparation on Environmental Impact Statements). EPA, Wexford. Environmental Protection Agency (2003) Advice Notes on Current Practice in the Preparation of Environmental Impact Statements. EPA, Wexford. Environmental Protection Agency (2002) Guidelines on Information to be Contained in Environmental Impact Statements. EPA, Wexford. European Union (2014). Directive 2014/52/EU. European Parliament and European Council. European Union (2011). Directive 2011/92/EU. European Parliament and European Council. Irish Statute Book (2018). European Union (Planning and Development) (Environmental Impact Assessment) Regulations 2018 (S.I. No. 296 of 2018). -

Toward Best Practices for Public Acceptability in Wave Energy: Issues Developers Need to Address

3rd International Conference on Ocean Energy, 6 October, Bilbao Toward Best Practices for Public Acceptability in Wave Energy: Issues Developers Need to Address 1 2,3 M. A. Stefanovich and J. Fernández Chozas 1Environmental Sciences Graduate Program Oregon State University, Corvallis 97331, Oregon, USA E-mail: [email protected] 2SpokApS, Blegdamsvej 4, 2200 Copenhagen, Denmark 3 Department of Civil Engineering, Aalborg University Sohngaardholmsvej 57, 9000 Aalborg, Denmark E-mail: [email protected] Abstract communities, the way they approach these communities will leave a long-lasting impression about At this initial stage of development, opinion the sector as a whole. Thus, developers act as good-will toward wave energy is mainly positive. Interviews ambassadors not only for their own projects, but also with developers, presentations about wave energy at for the WE sector. This article focuses on the issues local community meetings, and the literature show developers need to address when discussing WE that there are four main types of issues developers projects with local communities to achieve more need to address when discussing their projects with efficiently public acceptability. local populations: conflict of use of the ocean space, Public acceptability is not a new phenomenon - it environmental impact, NIMBY (Not in My Back has often been encountered with the adoption of new Yard), and community well-being concerns. The technologies, the placing of architectural monuments importance of these issues is presented and and works of art in public locations. Most of it has to suggestions for best ways to approach them are do not so much with the form or function of the new provided. -

The Economics of Renewable Energy

HOUSE OF LORDS Select Committee on Economic Affairs 4th Report of Session 2007–08 The Economics of Renewable Energy Volume II: Evidence Ordered to be printed 12 November 2008 and published 25 November 2008 Published by the Authority of the House of Lords London : The Stationery Office Limited £price HL Paper 195–II CONTENTS Page Oral Evidence Professor Paul Ekins and Dr Neil Strachan, King’s College London Oral Evidence, 6 May 2008 1 Professor AbuBakr Bahaj, Southampton University, Professor Tony Bridgwater, Aston University and Dr Simon Watson, Loughborough University Oral Evidence, 6 May 2008 8 Mr Benet Northcote, Chief Policy Adviser, Greenpeace, Dr Tim Jenkins, Economics Campaigner, Mr Dave Timms, and Ms Robin Webster, Senior Energy and Climate Campaigner, Friends of the Earth Oral Evidence, 13 May 2008 17 Mr Malcolm Keay, Senior Research Fellow, Oxford Institute for Energy Studies Oral Evidence, 13 May 2008 26 Mr Campbell Dunford, Chief Executive and Dr John Constable, Policy and Research Director, Renewable Energy Foundation Oral Evidence, 3 June 2008 36 Supplementary Written Evidence 45 Mr Philip Wolfe, Chief Executive, Renewable Energy Association; Ms Maria McCaffery, Chief Executive, British Wind Energy Association; and Mr William Heller, Chief Executive, Falck Renewables Limited Written Evidence (British Wind Energy Association) 55 Oral Evidence, 10 June 2008 63 Professor David Newbery, Cambridge University, and Professor Dieter Helm, Oxford University Written Evidence (Professor David Newbery) 71 Oral Evidence, 10 June 2008